This Saturday there’s a huge Commander event happening locally at Richmond Comix. Participants will be broken into four-person pods, the winner of each pod gets a seat at the finals table for a huge chaos melee, and the winner gets a judge foil Gaea’s Cradle.

On one hand, I’m super-stoked about the event. As most of my readers no doubt know, I’m a huge fan of Commander! I want nothing more than to see a room full of people playing multiplayer Magic and having a super-good time.

But having such a super-sweet grand prize gives me just a little bit of trepidation. There’s certainly incentive to "break it off" and construct a vicious and consistent killing machine that combo kills the table in the early game before most people have even had a chance to play anything fun. The Commander format is easy to break if that’s what people want to do.

So I pondered what to do about the situation. The folks who put the tournament together didn’t want to make up any extra house rules to prevent some of the more gross abuses the format is capable of doing; they wanted to give the players the freedom to play whatever style Commander deck they want.

How do I as just one player try to encourage the more fun lines of play? One option is to adopt a role as a regulator (something I’ve written about before), and the deck I’ve put together certainly has some of that going on. But then I thought why not offer up a sweet prize to reward what I—and many of the most ardent fans of the format—think are the kind of plays that epitomizes the spirit of Commander?

You know, the haymaker plays from which stories and myths are born!

"When choosing cards for your deck, ask yourself—is this card interesting and novel? Would I have nearly as much fun losing to this card as I would winning with it?"

A couple years back, when the Commander format really started taking off, over the course of a couple columns I touched on the topic of what Commander games are supposed to be all about. It’s obviously hard to boil down the format’s essence into something that’s quick to read and easy to grasp, but when I wrote the two sentences above, I knew I’d nailed it. I even tweeted them and got the attention of format fan Aaron Forsythe, who retweeted and favorited it. Commander is supposed to be about everyone sitting down and having a great time playing Magic together.

Obviously, within the technical confines of the game, there’s going to be one official "winner," but what we all really should strive for is to try to make sure as many people at the table have fun during the game as possible. Even if they don’t officially win, they still "win" if they leave each game with a smile on their face. So how do we do that, exactly?

Give ’em a good story to tell!

The best Commander games play out like a high-concept movie. For example, say one player jumps out in front with a strong play early and becomes the first obvious "villain." The rest of the players band together to try to take him down. Some might even sacrifice themselves along the way to help with the cause. Maybe the villain goes down in a blaze of glory, expending all his resources in some huge play that takes a few players down with him… Or maybe he’s only stopped because of the lucky topdeck of the player who seemed to be behind the whole game but managed to play some funky card nobody’s seen before that keeps her alive and able to steal the game at the last second. Think about the most fun you’ve had playing Commander—they’re like epic stories, right?

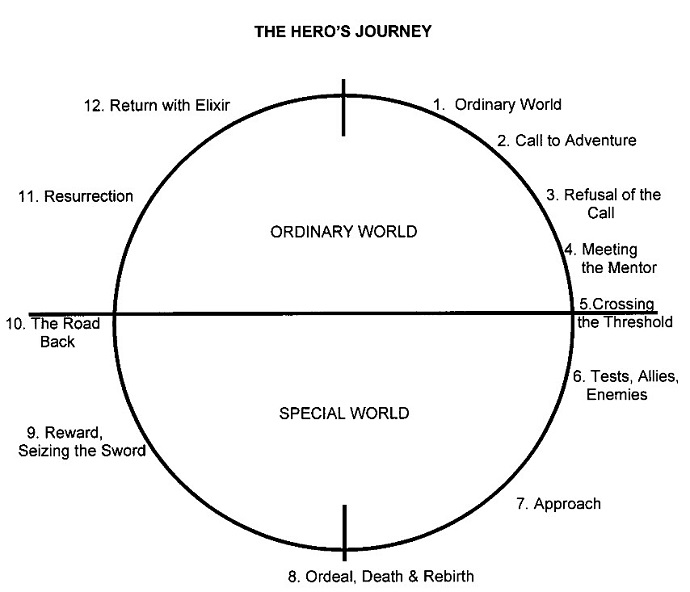

Thinking about Commander games as high-concept movies reminded me of a writing theory I learned about when studying screenwriting: The Hero’s Journey as presented by Joseph Campbell. In 1985, screenwriter Christopher Vogler wrote an influential memo called "A Practical Guide to Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces" and eventually wrote a whole book about taking Campbell’s ideas about The Hero’s Journey and applying them to writing successful screenplays for movies. Vogler wrote:

"In his study of world hero myths, Campbell discovered that they are all basically the same story—retold endlessly in infinite variations. He found that all storytelling, consciously or not, follows the ancient patterns of myth, and that all stories, from the crudest jokes to the highest flights of literature, can be understood in terms of the hero myth; the "monomyth" whose principles he lays out in the book.

"The theme of the hero myth is universal, occurring in every culture, in every time. It is as infinitely varied as the human race itself, and yet its basic form remains the same, an incredibly tenacious set of elements that spring in endless repetition from the deepest reaches of the mind of man."

Why do we as humans love great movies, great television shows, great books, and great comic books? Because we love stories! And you know what? Magic gives us tools to tell great stories! Sure, at its fundamental core, Magic is a game of strategy and skill, of math and probabilities, of analysis and reason…but Magic is also a game of magic and artifacts, battling sorcerers and armies of monsters clashing, heartbreak and laughter, tricks and traps and miracles. A great Magic card isn’t just a collection of stats and text, it’s also the art and flavor text, all of it coming together to provide a distinct element of character or plot in the story of each game of Magic.

There are many reasons why players are drawn to the game of Magic, but I think this ability to tell these mini-stories with your cards is a big part of why people love Magic. While one part of us may be trying to figure out how we can keep our equipped creature alive long enough to evolve into an unstoppable machine, another part of us is envisioning just how exactly—and why—our Human/Ooze Experiment One is wearing Riot Gear at the guild meeting. There’s a mini-story that plays out in our mind, brings a smile to our face, and maybe a chuckle that gets our opponent wondering what’s so funny.

In tournament Magic, there are limits to the kind of stories we can tell. If we want to be competitive, each element of our stories needs to be efficient, powerful, consistent, and a part of a distinct plan for victory. We can also expect our opponents to be similarly armed. There may be a few surprises along the way, but for a successful tournament story, usually the tried and true rule the plotlines.

Commander is the format where adventures of legend can be had! This is where you can dig into Magic’s deep and rich history of plot and character and pull out something obscure, something weird, something nostalgic, something silly, and put a smile on everyone’s face. I would argue that this is what Commander is supposed to be all about—a sense that we all just shared a kick-ass story for the ages!

I thought it might be fun—and instructive—to go through Vogler’s interpretation of The Hero’s Journey and note where each step might correlate with building and playing our Commander decks!

The Stages of The Hero’s Journey

1.) The hero is introduced in his/her ordinary world.

Most stories ultimately take us to a special world, a world that is new and alien to its hero. If you’re going to tell a story about a fish out of his customary element, you first have to create a contrast by showing him in his mundane, ordinary world. In Witness, you see both the Amish boy and the policeman in their ordinary worlds before they are thrust into alien worlds—the farm boy into the city, and the city cop into the unfamiliar countryside. In Star Wars, you see Luke Skywalker being bored to death as a farm boy before he tackles the universe.

For this stage, I’d say our ordinary world in Magic is a regular dueling scenario: one player versus one player, 40- or 60-card decks, 20 starting life, either tournament or casual. This is the world of Magic that we’re most familiar with.

2.) The call to adventure.

The hero is presented with a problem, challenge, or adventure. Maybe the land is dying, as in the King Arthur stories about the search for the Grail. In Star Wars, it’s Princess Leia’s holographic message to Obi Wan Kenobi, who then asks Luke to join the quest. In detective stories, it’s the hero being offered a new case. In romantic comedies, it could be the first sight of that special but annoying someone the hero or heroine will be pursuing/sparring with.

The call to adventure is when we first learn about Commander. Perhaps we walk into our game shop and see a big multiplayer game of Magic where people are playing cards we either have never seen or never expected to actually see play. It stirs something in us to consider that maybe there’s something more to Magic than the ordinary world we’re familiar with.

3.) The hero is reluctant at first (refusal of the call).

Often at this point the hero balks at the threshold of adventure. After all, he or she is facing the greatest of all fears—fear of the unknown. At this point, Luke refuses Obi Wan’s call to adventure and returns to his aunt and uncle’s farmhouse, only to find they have been barbecued by the Emperor’s stormtroopers. Suddenly, Luke is no longer reluctant and is eager to undertake the adventure. He is motivated.

The reluctance might be the strange rules unique to Commander or maybe concern about card availability, especially if you see people playing old cards like Gaea’s Cradle or planeswalkers you know cost a small fortune. But then perhaps you see a friend playing Commander who you know has been as firmly ensconced in the ordinary world of Magic as you, and he or she is having a great time!

4.) The hero is encouraged by the Wise Old Man or Woman (meeting with the mentor).

By this time, many stories will have introduced a Merlin-like character who is the hero’s mentor. In Jaws, it’s the crusty Robert Shaw character who knows all about sharks; in the mythology of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, it’s Lou Grant. The mentor gives advice and sometimes magical weapons. This is Obi Wan giving Luke his father’s light saber.

The mentor can go only so far with the hero. Eventually, the hero must face the unknown by himself. Sometimes, the Wise Old Man/Woman is required to give the hero a swift kick in the pants to get the adventure going.

At this point, you’ve found some guidance, someone giving you tips on how to build a budget-friendly deck, what to expect, how to maneuver through multiplayer politics. Maybe it’s a local friend, maybe it’s someone you just met at the local Commander game, or maybe it’s reading my primers (see the links at the bottom of each of my columns).

5.) The hero passes the first threshold (crossing the threshold).

The hero fully enters the special world of the story for the first time. This is the moment at which the story takes off and the adventure gets going. The balloon goes up, the romance begins, the spaceship blasts off, the wagon train gets rolling. Dorothy sets out on the Yellow Brick Road. The hero is now committed to his/her journey, and there’s no turning back.

You’ve picked your commander, you’ve found or acquired all the cards you need for your 100-card deck, you’ve got your dice, your tokens, your pen and paper, you’ve found out the place and time for the next Commander game, you’ve shown up on time, you’re caffeinated or inebriated or just high on life, you’ve shuffled up, determined who’s going first, taken your mulligans, have drawn your seven cards…and now you see how your adventure begins! What story elements does your hand contain? What commanders are your opponents playing, and what plotlines do they suggest? Who do you think you’ve got to worry about first? Who’s a potential ally?

6.) The hero encounters tests and helpers (tests, allies, enemies).

The hero is forced to make allies and enemies in the special world and to pass certain tests and challenges that are part of his/her training. In Star Wars, the cantina is the setting for the forging of an important alliance with Han Solo and the start of an important enmity with Jabba the Hutt. In Casablanca, Rick’s Cafe is the setting for the "alliances and enmities" phase, and in many Westerns it’s the saloon where these relationships are tested.

The initial turns go by. People have played lands and spells. Creatures and artifacts begin to populate the board. Somebody appears to be mana screwed. Someone jumps out fast with mana acceleration. Players begin jockeying for position, trying to persuade others to their worldview. You’re presented with your first challenge—perhaps you draw too many expensive cards and stall on mana, or you’re color mix is off, or one player begins to relentlessly attack you for what appears to be no good reason. How do you solve the problem and maintain your game plan? What sort of story is your deck encouraging you to tell now?

7.) The hero reaches the innermost cave (approach to the inmost cave).

The hero comes at last to a dangerous place, often deep underground, where the object of the quest is hidden. In the Arthurian stories, the Chapel Perilous is the dangerous chamber where the seeker finds the Grail. In many myths, the hero has to descend into hell to retrieve a loved one or into a cave to fight a dragon and gain a treasure. It’s Theseus going to the Labyrinth to face the Minotaur. In Star Wars, it’s Luke and company being sucked into the Death Star, where they will rescue Princess Leia. Sometimes, it’s just the hero going into his/her own dream world to confront fears and overcome them.

You’ve passed the early tests, you’ve made some allies and friends, and you’ve identified your enemies…and you see your end game coming together! It might not have been your original plan for how your deck was supposed to pan out, but now things are coming together. You’re sculpting your hand, you’ve got a plan, you’ve got the resources you need, and the big play is beginning to become clear. It’s going to be epic!

8.) The hero endures the supreme ordeal.

This is the moment at which the hero touches bottom. He/she faces the possibility of death, brought to the brink in a fight with a mythical beast. For us, the audience standing outside the cave waiting for the victor to emerge, it’s a black moment. In Star Wars, it’s the harrowing moment in the bowels of the Death Star, where Luke, Leia, and company are trapped in the giant trash-masher. Luke is pulled under by the tentacled monster that lives in the sewage and is held down so long that the audience begins to wonder if he’s dead. IN E.T., The Extraterrestrial, E. T. momentarily appears to die on the operating table.

This is a critical moment in any story, an ordeal in which the hero appears to die and be born again. It’s a major source of the magic of the hero myth. What happens is that the audience has been led to identify with the hero. We are encouraged to experience the brink-of-death feeling with the hero. We are temporarily depressed, and then we are revived by the hero’s return from death.

This is the magic of any well-designed amusement park thrill ride. Space Mountain or the Great Whiteknuckler make the passengers feel like they’re going to die, and there’s a great thrill that comes with surviving a moment like that. This is also the trick of rites of passage and rites of initiation into fraternities and secret societies. The initiate is forced to taste death and experience resurrection. You’re never more alive than when you think you’re going to die.

You begin to execute your plan, and some surprises stand in your way. Perhaps someone has executed their end game before you can set up and is threatening to win right now. Or perhaps someone counterspells the first part of your big turn. Or right before your turn someone kills one of your creatures or artifacts or enchantments that’s crucial to your story. Suddenly your story is in tatters, and you’ve got to scramble just to survive or to pull some sort of value from the wreckage. Were you just a glass cannon and are now hopelessly shattered? Or are you resilient, able to get back on path or construct a viable Plan B?

9.) The hero seizes the sword (seizing the sword, reward).

Having survived death, beaten the dragon, slain the Minotaur, our hero now takes possession of the treasure he’s come seeking. Sometimes it’s a special weapon like a magic sword, or it may be a token like the Grail or some elixir which can heal the wounded land.

The hero may settle a conflict with his father or with his shadowy nemesis. In Return of the Jedi, Luke is reconciled with both, as he discovers that the dying Darth Vader is his father and not such a bad guy after all.

The hero may also be reconciled with a woman. Often she is the treasure he’s come to win or rescue, and there is often a love scene or sacred marriage at this point. Women in these stories (or men if the hero is female) tend to be shapeshifters. They appear to change in form or age, reflecting the confusing and constantly changing aspects of the opposite sex as seen from the hero’s point of view. The hero’s supreme ordeal may grant him a better understanding of women, leading to reconciliation with the opposite sex.

You’ve made allies, you’ve struggled, you’ve had your plans shattered and redrawn, and you’ve played cards in ways you never envisioned when you first put them in your deck. Something surprising cut your way, and suddenly the big play is in your grasp, if only a few things stay in play one more turn and nobody has a counterspell…and YES! You pull it off—infinite Goat tokens, a crazy Warp World goes your way, you kill the guy that nobody’s been able to touch all game… When the smoke clears you’ve executed a haymaker play that has almost everyone at the table smiling as much as you are. This is a story for the ages! While no one might remember who wins this game a week or two from now, people will talk about this play for years!

10.) The road back.

The hero’s not out of the woods yet. Some of the best chase scenes come at this point, as the hero is pursued by the vengeful forces from whom he has stolen the elixir or the treasure… This is the chase as Luke and friends are escaping from the Death Star, with Princess Leia and the plans that will bring down Darth Vader.

If the hero has not yet managed to reconcile with his father or the gods, they may come raging after him at this point. This is the moonlight bicycle flight of Elliott and E. T. as they escape from "Keys" (Peter Coyote), a force representing governmental authority. By the end of the movie, Keys and Elliott have been reconciled, and it even looks like Keys will end up as Elliott’s stepfather.

After your haymaker, there might still be the game to finish up. Maybe you pull out the win, or maybe someone knocks you out afterwards. The Commander game needs to end so you can either start a new one or move on to whatever else you’ve got planned for the day or night. There might even be—fingers crossed—opportunity for more haymakers by yourself or others around the table!

11.) Resurrection.

The hero emerges from the special world, transformed by his/her experience. There is often a replay here of the mock death-and-rebirth of Stage 8, as the hero once again faces death and survives. The Star Wars movies play with this theme constantly—all three of the films to date feature a final battle scene in which Luke is almost killed, appears to be dead for a moment, and then miraculously survives. He is transformed into a new being by his experience.

There’s confirmation here that Commander is incredibly fun and worth the time and effort to play. Your opponents had a great time too, and everyone plans on further adventures together. You’ve got ideas for how to improve your deck or build a brand-new one. You’ve been inspired to try some new cards and plot how to go about acquiring them. Maybe you’ve gained some new respect for other players around the table, their card choices, their lines of play, and their haymakers.

12.) Return with the elixir.

The hero comes back to the ordinary world, but the adventure would be meaningless unless he/she brought back the elixir, treasure, or some lesson from the special world. Sometimes it’s just knowledge or experience, but unless he comes back with the elixir or some boon to mankind, he’s doomed to repeat the adventure until he does. Many comedies use this ending, as a foolish character refuses to learn his lesson and embarks on the same folly that got him in trouble in the first place.

Sometimes the boon is treasure won on the quest, or love, or just the knowledge that the special world exists and can be survived. Sometimes it’s just coming home with a good story to tell.

That last sentence says it all. At the end of the day, Commander is all about the stories you tell together with the players around the table. Considering the time and resources you spend planning and assembling the deck, not to mention the hours at the game table, don’t you want those stories to be epic? Don’t you want your opponents to recount those stories for days, weeks, months, and years afterwards? Really, who cares who might technically win an individual game of Magic—don’t you want to make the play that burns into other players’ memories and makes them want to share the experience with others?

To inspire players in the Commander tournament to reach for the epic plays, I’ve decided to award what I’m calling the Bennie Smith Spirit of EDH Haymaker Award. My good friend, the supremely talented, creative, super-sweet, and lovely MJ Scott of www.moxymtg.com, was kind enough to do some fantastic card alters for this award. Check ’em out!

I decided to pick these five because they’re legendary, they’re Dragons (Commander used to be called EDH [Elder Dragon Highlander] after all), and they’re also spirits, and since I’m trying to encourage legendary stories in the spirit of EDH, that seemed appropriate.

So how am I going to give these out? Well, first of all, a player needs to pull off some sort of play that knocks out one or more other players and does so in such a memorable way that leaves them smiling and very likely to tell the tale in the days, weeks, and months to come. Their victim needs to call out the play and nominate the player for the award, and then a majority of the rest of the opponents most vote to confirm. Then they much call me over to confirm that the play was indeed an epic haymaker in the spirit of Commander, and I’ll give him or her pick of the award cards remaining. I won’t veto the award unless there appears to be some collusion among players to game the award criteria, but I’m hoping that won’t really be a problem.

The main thing is I want to encourage and see what crazy stuff people come up with to bring fun and enjoyment to everyone at the Commander tables, not just who wins each game. Because if everyone is having an epic good time, then everyone wins!

And that’s truly what Commander is all about.

What do you think? Tell me in the comments below!

Take care,

Bennie

starcitygeezer AT gmail DOT com

Make sure to follow my Twitter feed (@blairwitchgreen). I check it often so feel free to send me feedback, ideas, and random thoughts. I’ve also created a Facebook page where I’ll be posting up deck ideas and will happily discuss Magic, life, or anything else you want to talk about!

New to Commander?

If you’re just curious about the format, building your first deck, or trying to take your Commander deck up a notch, here are some handy links:

- Commander Primer Part 1 (Why play Commander? Rules Overview, Picking your Commander)

- Commander Primer Part 2 (Mana Requirements, Randomness, Card Advantage)

- Commander Primer Part 3 (Power vs. Synergy, Griefing, Staples, Building a Doran Deck)

- Commander Starter Kits 1 (kick start your allied two-color decks for $25)

- Commander Starter Kits 2 (kick start your enemy two-color decks for $25)

- Commander Starter Kits 3 (kick start your shard three-color decks for $25)

My current Commander decks (and links to decklists):

- Lord of Tresserhorn (ZOMBIES!)

- Borborygmos Enraged (69 land deck)

- Aurelia, the Warleader (plus Hellkite Tyrant shenanigans)

- Oona, Queen of the Fae (by reader request)

- Karador, Ghost Chieftain (my Magic Online deck)

- Karona, False God (Vows of the False God)

- Skullbriar, the Walking Grave (how big can it get?)

- Phage the Untouchable (actually casting Phage from Command Zone!)

- Johan (Cat Breath of the Infinite)

- Niv-Mizzet, the Firemind (Chuck’s somewhat vicious deck)

Previous Commander decks currently on hiatus:

- Yeva, Nature’s Herald (living at instant speed)

- Nefarox, Overlord of Grixis (evil and Spike-ish)

- Niv-Mizzet, Dracogenius (new player-friendly)

- Trostani, Selesnya’s Voice (new player-friendly)

- Jarad, Golgari Lich Lord (drain you big time)

- Riku of Two Reflections (steal all permanents with Deadeye Navigator + Zealous Conscripts)

- Phelddagrif (Mean Hippo)

- Sigarda, Host of Herons (Equipment-centric Voltron)

- Bruna, Light of Alabaster (Aura-centric Voltron)

- Ruhan of the Fomori (lots of equipment and infinite attack steps)

- Ghave, Guru of Spores (Melira Combo)

- Glissa, the Traitor (undying artifacts!)

- Grimgrin, Corpse-Born (Necrotic Ooze Combo)

- Damia, Sage of Stone (Ice Cauldron shenanigans)

- Geist of Saint Traft (Voltron-ish)

- Glissa Sunseeker (death to artifacts!)

- Jor Kadeen, the Prevailer (replacing Brion Stoutarm in Mo’ Myrs)

- Thelon of Havenwood (Campfire Spores)

- Melira, Sylvok Outcast (combo killa)

- Konda, Lord of Eiganjo (The Indestructibles)

- Vorosh, the Hunter (proliferaTION)

- Progenitus (Fist of Suns and Bringers)

- Savra, Queen of the Golgari (Demons)

- Uril, the Miststalker (my "more competitive" deck)