The idea of Magic cards having fixed, global prices is relatively recent.

For years, Magic finance was far more provincial. Los Angeles, for example, has always been combo country. For years, combo pieces (and anti-combo cards like Force of Will) have been more expensive here than in other parts of the world. Before large online retailers, card prices varied from shop to shop and playgroup to playgroup. Most retailers had a basic idea of what the staples should be worth, but beyond that it was all down to the people pricing the cards. Back in 2003, a decade ago but still ten after the advent of the game, several of my local stores still used the latest issue of Scrye to price their singles. Others based their prices off local demand or guesswork. Finding bargains was nice, but it was very frustrating when the only available copy of a card you needed for an event was priced at five times the going rate.

Back then, it was common for players to trade entirely based on their own gameplay preferences without any thought toward value. Angels and Dragons, for example, would always trade well. I knew several store regulars who were always happy to trade their fetchlands and duals for the latest giant beaters. These players didn’t make these lopsided trades just once before wising up—they made them every single week for years. It was the Wild West of Magic finance, and it lasted for quite a long time.

I’ll be sharing my full Dragon’s Maze set review with all of you next Monday, so with the eyes of the Magical world gazing at the future, I thought it would be fun to take a short look back at what trading and speculation was like in the 1990s and early 2000s. I reached out to my friends, fans, and followers on Twitter and compiled a few interesting tales from a time before social media and live streams. These stories are relevant today because Magic trading has always been about taking advantage of imperfect information. A decade ago, doing this was fairly easy—anyone with knowledge of Internet pricing was at a distinct advantage when trading with people who didn’t care what their cards were worth.

When smartphones first started to catch on, value traders were slow to adjust. The popular (and frustrating and slimy) new trading strategy was to spam “what do you value this at?” at your trade partner until you found something he didn’t know the real price of. Today, it seems as though almost every player is financially savvy. Today’s trade market is all about small but significant advantages—trading for cards with financial upside, say, or exploiting the difference between cards that have the same retail price but different buylist values.

As the speed of technology and information increases, we traders are always looking for an edge over the competition. Sometimes, the best way to find one is by examining trends over the long term. What was trading like in 1993? 1998? 2002? What shook up the world of Magic finance in its earliest days? How long have trade sharks existed, and have they always operated the same way? The best way to theorize about how trading might evolve into the future is to look into the past and examine the whole picture. That is what we are going to be doing this week.

…

Things that are manufactured to be collectible rarely end up being worth much. The disposable baseball cards that came with cigarette packs are still worth thousands of dollars, for example, while the embossed and foiled baseball cards from the 80s and 90s aren’t worth the paper they were printed on. This is why the first few sets of Magic cards will always be valuable—people didn’t buy Alpha and Beta cards to hoard in a vault; they bought them to shuffle up and play with because the game was groundbreaking. Moxen and Black Loti were desirable back then, of course, but did Magic cards have value before they had concrete prices?

I wasn’t playing the game back then, so I turned to Twitter followers like Michael Murphy, who was an avid Midwestern player at the time. “Scrye created the finance world of Magic,” Michael told me. “Each local game shop had their own prices on stuff before that, and each area had their own house rules. Even though baseball cards have been around forever, people didn’t really view their Magic collections in the same way.

The only real way to win was with a Channel Fireball or with creatures. Shivan Dragon, Serra Angel, Force of Nature, Sengir Vampire, and the like were the big dogs of the day. Two days before our local game shop got a Scrye, we traded a Shivan Dragon for two duals and a Sol Ring. Our local house rules were such that Moxes were absolutely worthless. We had about fifty of them pinned up in the bathroom of the store.

When we got that magazine, life changed drastically. Our local shop took down our wall of Moxes, and the employee disappeared with them. Everyone was carrying one around and trading got a lot tougher. Before Scrye, you had to give up a set of duals, a set of Moxes, a Lotus, and a Shivan for Ali from Cairo. After it? No way.”

Eastern Pennsylvania player Tim Stoltzfus had a similar experience with Moxen. “I played mostly at a store called Gamemasters who did a lot of business in Magic and has long since disappeared,” he told me. “During the days of Beta and Unlimited, in that area Moxes were not highly valued because ‘they were just a land except they ate up a rare slot.’ The owner of the store started trading a booster pack to anyone who opened a Mox and wanted to get rid of it. I still remember the small white cardboard box that had at least two hundred Moxes in it.”

Magic player Mark Nugent shared his story with me as well. “Scrye and InQuest were used for a way to know which cards were rare, uncommon, or common.” He said. “The pricing wasn’t always accurate, and people used them as guides not as an accurate evaluation of a price, especially with the release of a new set. I remember when Ice Age and Alliances were first released you had to trade on instinct.”

Tim remembers it the same way. “We had no idea what ‘playable’ actually meant,” he said. “I still remember opening up a Taiga and going ‘So what’s the big deal? It makes mana,’ and subsequently trading it for an Artifact Possession because that was a great way to kill the guys who were playing Winter Orb / Icy Manipulator. Even after Scrye came on the scene, trading piles of commons and uncommons to help people finish sets was very normal regardless of what was actually in the stacks.”

A European player who wanted to be credited as ‘pi’ agreed. “When a new set was released, cards would become available right away,” he told me, “but it would take a while before the new magazine came out and we were pretty much in the dark on prices. I remember trading three uncommons (one was an Overrun) for a Stroke of Genius because I know it was going to be an expensive card soon.”

“There has been an evolution of card values ever since the game originated,” Chad O’Brien said. “I got into the game back in 1994. Antiquities had just come out, and our local shop had a box for sale. The rub was that boosters of Antiquities cost $5.00 as compared to the $2.50 for a booster of Revised. Even then I remember asking the shop owner, “Why would anyone buy a pack of this? It costs twice the price.”

He replied, “The cards in here are harder to get.”

The thing was that you didn’t even know what the cards that were hard to get were. There was no Internet, so there was no way of establishing a list of cards or what they did. Besides, you didn’t need hard to get cards because powerhouses like Shivan Dragon and Force of Nature were in Revised.

Everyone wanted a Shivan Dragon because he flew and was a 5/5 that got bigger. Force of Nature didn’t fly, but should you get your hands on a Berserk, you could kill your opponent just like that. If you opened a pack of Revised to find a land as your rare, you were bummed. What good were lands? You got a bunch in every pack anyway.”

Tim shared a story about this era with me as well. “The day a new set showed up in stores was a feeding frenzy of boosters being opened and trading as players discovered new cards for the first time,” he said. “The coolest trade I have ever done was the day that The Dark came out. One of the owners of Gamemasters collected four of every red card printed. I had ordered three booster boxes of The Dark and was at the store tearing them open.

The owner, however, didn’t open any for himself. He relied on his customers to take care of his collection. He still had his box of Moxes, and myself and another regular who had opened a few boxes were there sorting when the owner presented us with a proposal. Between the two of us, if we supplied him with four of each red card from The Dark, he would give each of us a Beta Mox Ruby. At that point, a Beta Mox Ruby sold for around $125-$150. The two of us ended up spending at least two hours going back and forth over who would put in what cards to satisfy the trade.

“Ok, I’ll put in four Goblin Rock Sleds if you put in four Goblin Shrines.”

“I only have exactly four Goblin Shrines. Let me keep one, put in a Goblin Caves instead, and you put in the fourth Shrine.”

We went back and forth like that forever, but eventually we acquired the coveted Mox Rubys.”

When thinking about what Magic was like in 1993 or 1994, it’s important to remember what games were like back then. If you wanted to play a card game, you were generally limited to only what you could play with a deck of playing cards. Board games hadn’t had their renaissance yet, even in Europe, and we were still a year or two away from Settlers of Catan. The SNES was the current console, and Doom was only a month or two old, so video gaming was mostly still for children. The idea that people from all ages and walks of life would ever attend a card tournament in huge numbers on Friday night was stupefying. If you were a rather big nerd, you probably played Dungeons and Dragons, but that was probably the extent of it. There were a few gaming conventions like Gen Con, but they were much smaller and further out of the mainstream.

At that point, there was really no precedent for Magic cards ever being worth something beyond their immediate play value. Even the idea of trading cards to help improve your deck was alien. People certainly traded baseball cards to finish complete sets, but this was more like trading for extra Draw Four Wilds in order to help your Uno strategy. It’s easy to laugh at people who refused to play blue or traded their Mox for a Shivan Dragon in retrospect, but it makes sense when you pull back and think about Magic as if it were any other game. What if you could rig the deck in Agricola so you always drew your favorite professions? Or you always got your favorite route maps in Ticket to Ride? I doubt you’d be thinking too much about the monetary value of the cards when making those trades.

After a few years, though, the value genie was entirely out of the bottle. For better or worse, Magic cards were worth money now. And as you’d expect, the value traders weren’t that far behind.

“What I would do was trade all day: up, down, left, right. As long as there was a profit to be, had I’d make deals,” pi told me. “I was sometimes working at up to four deals at the same time. I was keeping track of what people were looking for so that I could trade for it when someone else had it in their binder. By the end of the day, I’d walk up to the dealer to trade in my gains for something big. My best score was an Alpha Ancestral Recall.”

Of course, it wasn’t just players that took advantage of this brave new world. Dealers did too—especially those who also played competitively. “I remember when the card availability was so small that stores bought them up to deny other players from playing them in a PTQ,” Jeffrey Szelzki told me. “My worst trade was my Force of Will for four copies of Stampede Driver. I needed the Stampede Drivers, and no store had them in stock due to the lack of singles during that time.”

“Lack of card availability led to some insane transactions even by the standards of the era.” Joey Marsillo shared. “I saw a Mox traded straight up for a Jester’s Cap, and the guy who traded the Jester’s Cap was really reluctant to let go of it. The local card shops didn’t have any Caps, the Internet wasn’t an option, and no one else had one for trade. What else could be done?”

“Sharking new players was rampant and insanely easy,” Joey went on. “Anyone with a decent sized collection could trade a huge stack of commons for, say, a Shivan Dragon. Sometimes it wasn’t even that difficult since lack of knowledge of rarities and relative splashiness of cards could allow for extremely lopsided transactions. Marking rarity by expansion symbol is one of the greatest things Wizards of the Coast ever did because without a Scrye/InQuest/Conjure/etc. handy, there was no easy way to discern rarity let alone value, and seeing Craw Wurms traded for dual lands was not uncommon at all.”

Chad had a different view of what trading was like back then. Since most players didn’t concern themselves with value, what Joey describes as “sharking” he considered savvy business. “When it came to trading,” he told me, “Scrye [prices] didn’t come into the picture. Scrye was used by some dealers who insisted there was a global market for cards. This wasn’t really true—in reality, there was only a local market for cards. I remember figuring out the value of dual lands and how they played a role in multicolored decks. I stocked up on Shivan Dragons just to trade for dual lands, having had a feeling that other people would eventually begin recognizing their value. I would go through binders and say, “Oh, you have dual lands—do you like them?”

Their response would almost always be, “No. Not really.”

“What are you looking for?”

“Shivan Dragon.” It was always Shivan Dragon.

“Well, I have a page of ’em. How many do you need?”

“Um…two?”

“How many dual lands will you give me for two?”

“Uh…six?”

They had a card that they felt was useless to them, and I was trading a card I didn’t value as highly as they did. Everyone walked away happy.”

Jeffrey disagreed. “You think sharks are bad now?” he told me. “They were hunting anyone and everyone with a Force of Will or anything remotely valuable. You wouldn’t be able to get away from them. If they had their eyes set on a Force of Will, you weren’t leaving with it.”

These conflicted memories encapsulate what the era was like for me as well. Back when I was 15 or 16, I considered myself a savage trader. I was constantly making deals, often two or three at a time, and my knowledge of prices always meant that I came out ahead. My friends were always in awe of how many absurd cards I’d end up with at the end of the night.

At the same time, because so few people cared about value, I was always one of the most popular people in my local shops. People would swarm me with their binders when I walked into the store, and I often dealt with the same trading partners for months or years at a time. People loved trading with me because I had almost everything and it was all for trade. Before you could place an order online and have a card show up at hour house a few days later, having a lot of cards gave you a massive advantage. I never needed to pressure people or use normal “shark” tactics because people would walk right up to me and offer me amazing deals. I just had to be there and know which cards were worth money.

I did run into the real sharks from time to time, though. My binder may have been packed with all of the latest and greatest goodies from my local stores, but I didn’t have access to any of the eye-popping cards from the earliest days of the game. To get those, I had to go to a large event—usually a regional Prerelease—and swim with the big boys. I always came out of there with my head spinning and my binder far lighter. It didn’t matter much to me, though, because I had made so much value trading locally. I was fine giving a lot of it up to get the cards I actually wanted.

Of course, there were a few times when value mattered to nearly everyone: when the prices of well-loved cards tanked. “When Italian Legends came out,” Joey Marsillo told me, “there was a schism in my local community about [the set.] Some people bought a ton of them to get access to cards that were prohibitively expensive. Others thought that was cheap and refused to have anything to do with Italian Legends since they were viewed as barely a step above proxies. When I had the opportunity to buy two Italian Mana Drains for $4 each, I refused on the grounds that they weren’t “real” Legends.”

“Chronicles was fairly miserable. 4th Edition was bad too,” Mark Nugent told me. “Killer Bees and Carrion Ants were twenty dollars each before Chronicles, and they have never recovered. The Elder Dragon Legends also took a huge tumble. They were right behind the Power 9, Juzam Djinn, and Ali from Cairo for most expensive cards. Nobody really knew how to prepare for the Chronicles printing. I remember seeing a page or half-page advertisement in InQuest or Scrye for it and wondering what was going to be in it. We didn’t have the speed of communication then that we do now.”

“Fallen Empires was an epic disaster,” Matthew said. “After Scrye came out, our rule was to always trade white bordered cards for black bordered ones. The day Fallen Empires came out, our trader traded two Moxes (Unlimited) for a set of it. We had also bought a couple boxes that morning, and none of us had cell phones. The trader shows up and was like ‘look what I got!’ And we had already opened the boxes and had a complete playset and then some.”

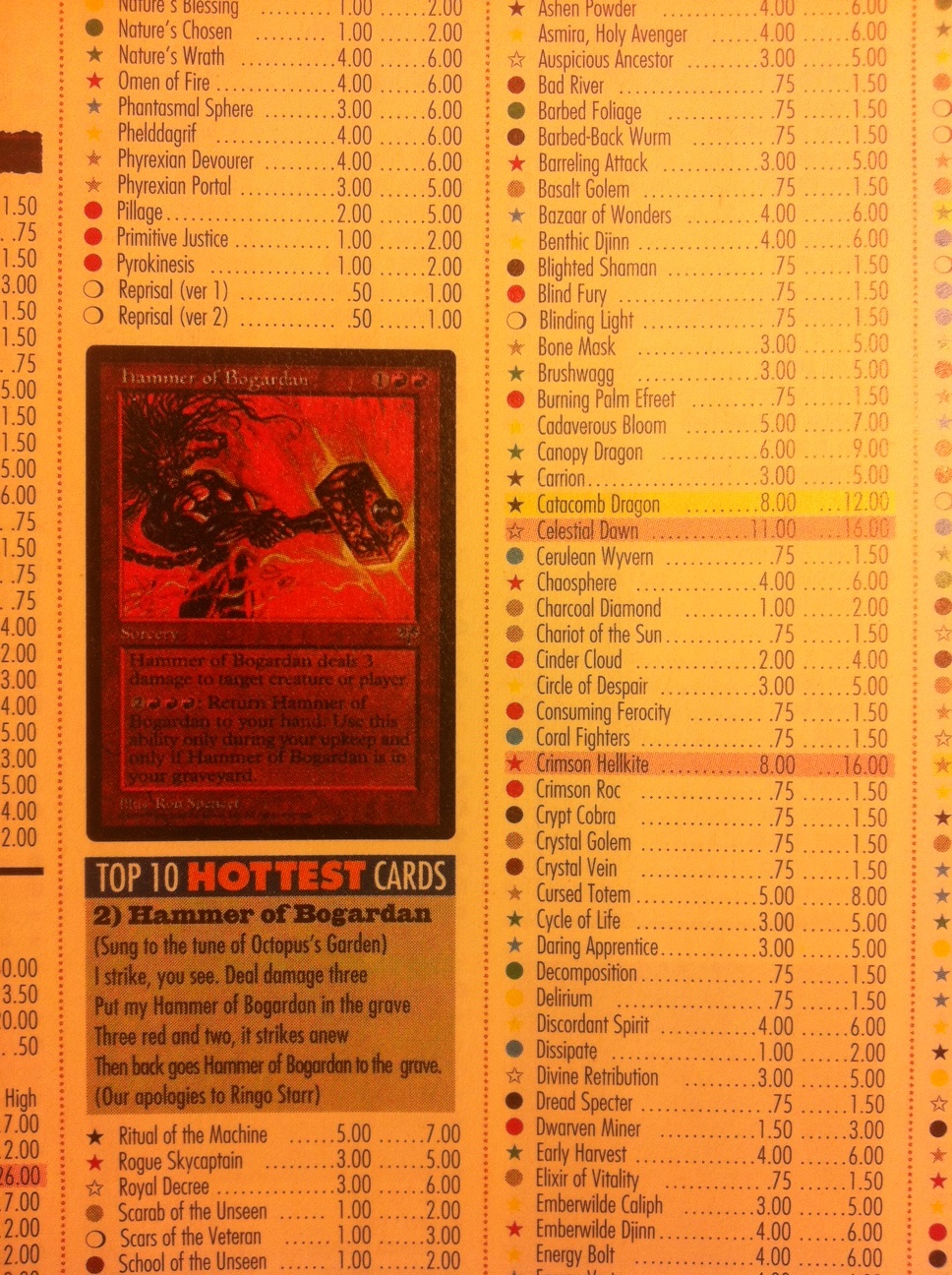

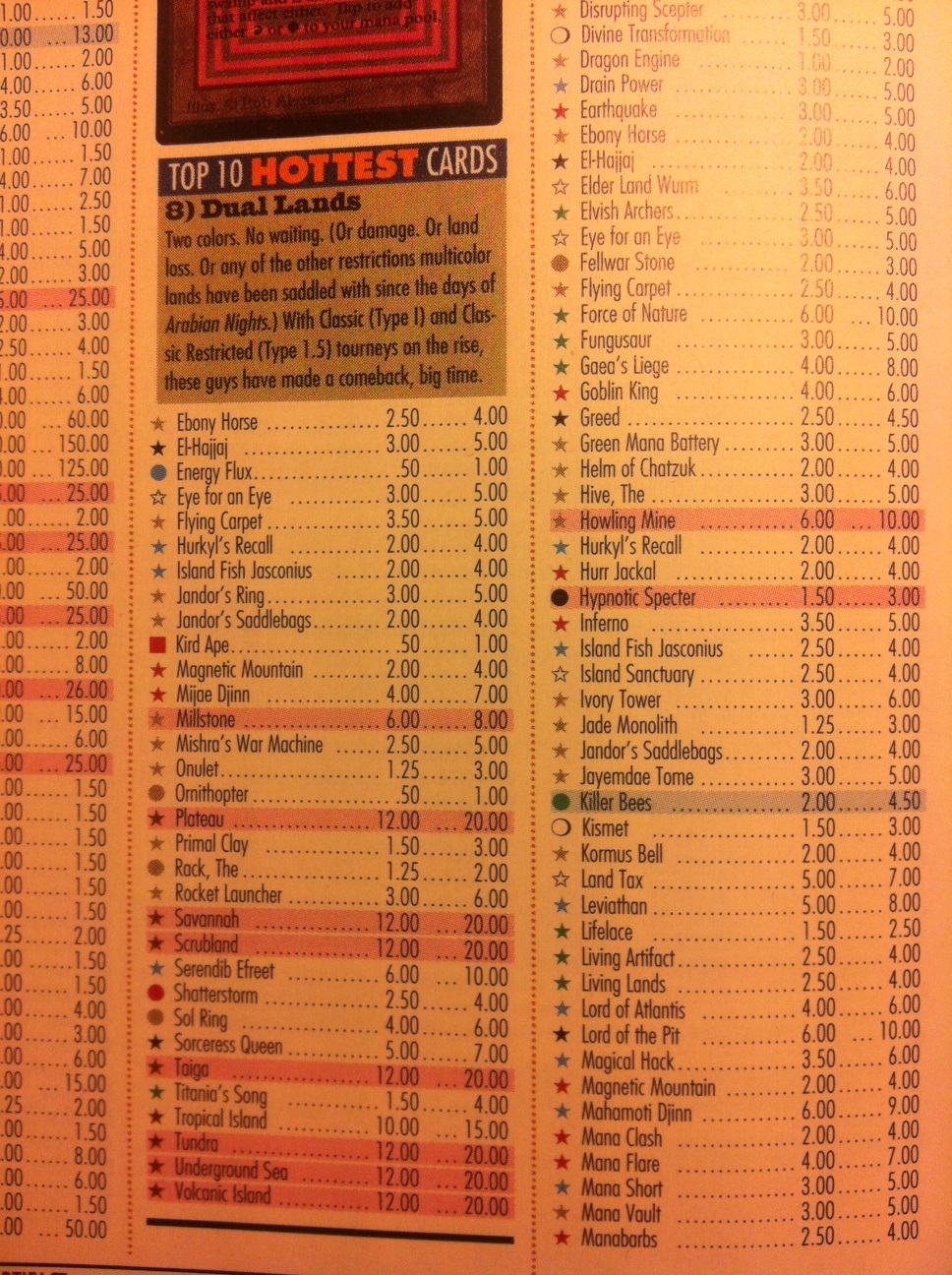

It is interesting to look back and see which cards were valuable from the start and which only gained value later on. Jester’s Cap might be close to a bulk rare now, but you would have had to trade multiple dual lands to get one in 1996. Tradewind Rider was the chase rare from Tempest. Lion’s Eye Diamond was worth nothing. Here’s a picture of a page from InQuest magazine in 1997:

I love looking through these old magazines because it really shows you how ephemeral prices are. Note that the three “hot” cards that have been highlighted here are Catacomb Dragon, Celestial Dawn, and Crimson Hellkite—not exactly a murderer’s row of value in 2013. Of course, people back then did have some knowledge of what a good card was. Check out these scorching hot dual land prices:

I know, I know, I wish I had a time machine too.

What has changed the most about trading? “As technology became more readily available, you began hearing things like ‘what do you value this at?’ with more frequency,” Chad told me. “This statement was usually followed up with ‘let’s look it up.'”

Gone are the days of finding people who just collect Dragons or Angels. It was great to trade with those people because they didn’t care about value—they cared about getting that Dragon they’d never seen before. They didn’t care about their Force of Will because they didn’t play blue. Things changed, and value became a predominant factor. Trading became less fun because it became a grind. Granted, there was an advantage that value traders had over casual traders—but the point really is that prior to StarCityGames.com and smartphones, trading was fun because you could give someone something they wanted and you could get something you wanted in return. Everyone was happy because no one felt ripped off. I remember trading and saying, “I’m getting a better deal here.” Their response? “Throw in another Dragon.”

Pi disagrees. “I don’t see a real difference between early 2000s value trading and current day value trading in a sense that many of the theories and strategies people employ today were part of my arsenal back then,” he said. “What is different, though, is the speed at which prices change, how smartphones generally make trades last much longer, and the amount of information available.

Back in the day one would arbitrage between different groups of players, picking up cards undervalued in one group to trade with people that overvalued them in another group, but these days those opportunities rarely exist on such a small scale.”

Magic trading has changed a lot over the past two decades, but so has the world. It wasn’t just the Magic singles market much more regional in the middle of the 1990s; it was everything. Before the Internet became mainstream, it was possible to exploit regional arbitrage in thousands of different industries. Cities and towns had distinct identities and preferences. Access to instant information has made things much more homogenous.

Access to more information makes it easier to exploit market inefficiencies, but at the same time it makes it so that there are fewer of those inefficiencies to begin with. The Internet made it easier and more profitable to be a shark, but it also made it easier to defend against them. This is how we’ve gotten to where we are now: a world where trading has become a frustrating and paranoid activity.

I do think that will improve. As we slowly get used to an era of smartphone trading and massive swings in international card prices, trading will stop being being about trying to gain immediate value in any particular deal. The future lies in dealing not with what a card is worth now but what it is likely to be worth in the future. The great traders won’t be sharks—they’ll be prognosticators. Once enough value traders get on board with this, people will become less paranoid about making deals. The future of Magic trading is bright, even if we’re not quite there yet.

This Week’s Trends

– With Notion Thief about to enter Standard, people are starting to get excited about Whispering Madness all over again. I absolutely loved this card when it was spoiled for Gatecrash and recommended it as a buy at $1.50. Well, it’s down to $0.50 now, so I’m hoping I can at least make my money back. If the deck does work, I’d expect the card to rise into the $2-$3 range.

– I know half the cards in Dragon’s Maze seem to destroy Sphinx’s Revelation, but it’s still the hottest card in the universe right now. If you can trade for these from people who think it’s about to be hated out of the format, do so. Its demise has been greatly exaggerated.

– Jace, the Mind Sculptor is still rising. I still don’t want any part of him as a spec target. If you already have a copy or two, enjoy the ride.

– The textless version of Putrefy is worth picking up in trade if you can. People are going to want these in Standard now that the card is being reprinted.

– Have you checked the price of Maelstrom Archangel lately? It’s up to $10 on StarCityGames.com and higher on other sites. I see this card hitting $15 due to casual demand in the next few months.

– People have been asking me about Dragon’s Maze speculation targets, and so far I haven’t seen any great ones. My favorite target in general are mythic rares that start at $5 or less, but the only one right now is Maze’s End—all the others are $8 or more. I kind of like Breaking—at $2 it is most of a Glimpse the Unthinkable. I could also see Flesh // Blood being played in Jund thanks to its versatility early and late in the game. I adore Notion Thief, but I’m biased because it’s the kind of card I love to play with the most. Otherwise, I’m waiting to see what the rest of Dragon’s Maze bring and how the prices behave over the next week or so. Join me on Monday for my set review!

Until then –

– Chas Andres