There are a lot of ways that you can playtest, both good and bad. If you’re a StarCityGames Premium member, the chances are high that you do, on occasion, playtest. Playtesting is one of those things that is really most akin to studying. If you like the subject matter, studying can be kind of fun sometimes, but for most people, whether it is fun or not, the point isn’t to have fun, but rather to learn.

People that playtest, though, are largely fooling themselves. I would wager that something like 5% of people that are playtesting actually have a good gauge of how well (or not well) they are measuring their games. And if your goal is to accurately measure how a particular matchup will go, I’d guess that a significant amount less than 1% of you are actually playtesting “correctly.” I sure as hell know that I am not one of them. The difference is, I do know what kind of value I’m getting back for any of my playtesting, and that can make all of the difference.

Playtesting — The Common Method versus The Accurate Method

Most people that playtest do this: play one deck against another for about 10 games, do the simple match, and call that their “Matchup Percentage.” The reason that this is so common is that it is one of the most efficient ways to actually get a modicum of results. There is nothing wrong with this, particularly, so long as you recognize that it is only the most rough snapshot of the way that reality actually works.

Let’s take the example of a true “50/50” matchup. To run a simple experiment I will flip a coin a few times (say, 10). In my first trial of this 50/50 matchup, heads won seven to three. Trial two: 50/50! Trial three: three to seven. Trial four: six to four. Trial five: two to eight! Wowsa! Overall, in the fifty flips, that was 23 to 27, pretty close to 50/50 even though in one set it looked like a 20/80 matchup.

When you think about another factor, going first, the problem seems even more compounded. For most Constructed deck matchups, you want to go first. Your deck seems to perform better. How much better? Well, in some matchups, it might not be that consequential. If we measured it, maybe it would show up as a +1% on the matchup. In others, though, maybe it would show up as something truly radical, like a +20%. In fact, maybe that 50/50 matchup is actually a 60% on the play and a 40% on the draw. Obviously, that is an intense example. Something more common, in a 50/50 situation might be a 55/45 split. Even that, though, is very significant.

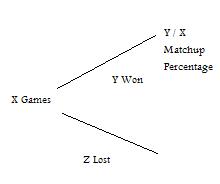

So, where the common playtesting might look like this:

The matchup math here is represented by a pretty simple equation: Y / X. Play 10 games, win 6 of them, 60% matchup! But we already know the problem with that…

What it really ought to look like, just to get a proper match math, is something like this:

The final matchup percentage? Well, it would be this:

(.5 * D * Y) + (.5 * D * Z * T) + (.5 * E * T * Y) + (.5 * I * Y) + (.5 * I * Z * T) + (.5 * J * T * Y)

Simplifying down to:

((D+I)(Y+ZT) + (E+J)(TY)) / 2

Since we can express losses in terms of wins (1 — chance of winning), this further reduces to:

((D+I)(Y+T-YT) + (2-D-I)(TY)) / 2

Yikes! Sooo, if you know your Playing First Win Percentage, your Playing Second Win Percentage, your Playing Second Sideboarded Win Percentage, and your Playing First Sideboarded Win Percentage, and if your numbers are accurate, you will have an actual matchup percentage that is worth paying attention to. The easiest way to do this is to play however many game 1s playing first and then second, and then however many sideboarded games, playing first and then second, record those numbers, and then do the math.

Okay, hands up. How many of you do this?

For the ten of you out there that raised your hands, I salute you. For the rest of us mere mortals, we have to pick and choose, usually, to get results that are useful. Let’s go through some of the things that are common techniques in playtesting. (By the way, the above method is actually a fantastic means of playtesting, given sufficient resources…)

Testing for Measurement / Testing for Discovery

This is a common dichotomy in playtesting. What on earth are we playtesting for? And, is my playtesting partner even on the same page?

Testing for measurement is the act of attempting to gauge how well a deck performs in different circumstances. Testing for discovery is the act of attempting to explore new territory in deck design. In most cases, this is a continuum (like the Kinsey scale, among others). Very rarely are we testing solely for measurement or solely for discovery. Usually it is both, and the pendulum is typically weighted slightly towards the “measurement” side of the scale.

Testing for measurement is most useful when you have two decks that are already proven in some manner, or at least semi-proven. You pit two decks against each other and you measure the effects of the interaction. Which deck wins? Why?

Testing for discovery is most useful when you are looking to see if there is anything fruitful about going into a new deck space. Is your new combo deck sound, or is it incoherent?

When you are building new decks, the actual measure of how a deck performs is hardly important. You are attempting to figure out where the deck is lacking or what avenues the deck already has that seem worth exploring. In this sense, you might have a deck that isn’t actually doing very well, but every time a particular event happens, the deck just explodes into silly goodness. In your next reworking of the deck, you remodel it after that.

As you hone decks that are more and more proven, inevitably you will go into measurement. Your deck itself will often largely be set, but you want to measure the effects of, say, an extra colored land in the deck, or a fifth Elf “effect.” Perhaps you’ll decide a few more burn spell are useful, or more counters. Whatever the case may be, at some point you need to be in the measurement stage.

Anyone who is a prolific deck builder will tell you that the discovery phase of testing is incredibly important. For every deck worthwhile, there will often be a veritable graveyard of poor decks that had to be discarded to get to the potentially good one. Every good deck-honer and tourney player will tell you that accurate measuring of decks is incredibly important as well. You need to have a good sense of how your deck actually performs.

What is most important here is recognizing which mode of testing you are in. It is not useful to constantly be in measurement mode. If you do so, all you will do is always play rehashes of what is already out there, without innovation. You are going to have to bank on the sheer power of the deck and your own play skill. Conversely, staying in discovery-land is also problematic. At some point you need to know when to start measuring. If you don’t take measure, you could waste forever on a deck that, at its best, is not a contender. Teams of Magic players are particularly useful because some people are better at one skill than another, and you can thus reap the benefits of both necessary elements of the process. It must always be remembered, though, that working both sides will lead to the best results.

Take Backs / No Take Backs

The question of playtesting “take backs” is an interesting one. The answer about which way to go on it, as is often the case in playtesting, depends on what you want to get out of your playtesting.

“No take backs” is often the rigorous school put forth by old-school luminaries like Mikey P., among others. If you are trying to prepare for actual events, this is a very useful thing to do. First of all, it really does matter if you have a complex deck that might muck up your opponent’s expectations and cause them to make mistakes. Similarly, it will absolutely matter if you are the one making the mistakes because your deck provides you with so many opportunities to make the error. For it to be useful, it does require that you are applying the model accurately, though. If you’re preparing for play at the Pro Tour or Grand Prix, and your opponent is a fledgling FNM player, you can expect that they are going to make any number of mistakes that your opponent’s won’t be making at the big event.

The thing that “no take backs” does, though, is train you. By applying this rule, you can make yourself do the actions that will result in a ‘mind-of-no-mind,’ a kind of sense-memory, or intuitive knowledge of the right play, based on actually having found it in playtesting again and again. Allowing take-backs will rob you of some of this preparedness.

On the other hand, “no take backs” also will often increase the stakes of every single play that you make in games. This means that your playtest will slow up like syrup. Whereas a sloppier playtester might get in something like 20 games over some amount of time, the deliberate playtester will get in something closer to half that (or worse).

There is also learning value in take backs. You can learn strategic and tactical maneuvers that might actually be employable in a game situation. So long as you can accurately recreate the changes that have happened in the game, it is possible that you can discover, for example, that attacking a different resource can result in a much more advantageous game state. When you recreate this change in a different game, you might find that this is often the case with whatever tactic you are employing.

“Take backs” / “No take backs” basically breaks down like this. If you want to improve your play, “no take backs” will serve you best. If you want to improve your knowledge of strategy and tactics in a matchup, careful use of take backs will be helpful.

The Question of Mulligans

How do you mulligan in playtesting?

For some, the answer is simple. They follow the official tournament rules. Every time.

This is the best way to playtest if you have the time. Given enough trials, these mulligans will work themselves out. However, sometimes you don’t have the time to playtest the proper amount of iterations. In these cases, shortcuts can be employed.

One of the best “common” mulliganing shortcuts is to mulligan to six twice, then to five twice, etc.. If you employ this method, you have to “pretend” that you would actually have to go down to the smaller hand size when making your mulliganing decision. In a sense what you are doing is “normalizing” your results, by removing the outlier games. The rationale goes like this, for example, “Well, I know that mulliganing to four will mean I lose! What have I gained by playing it out?!” There is a little something to this, hence the shortcut playtesting mulligan.

But it is still problematic. Your deck will mulligan. Sometimes it will mulligan a lot. If you just ignore the mulliganing of your deck, you are impacting the results of your testing. The normalizing that you are performing by mulliganing in the improper way has utility only because you are performing a largely inaccurate modeling most of the time anyway, if you are using a small number of iterations. If you’re putting in the real deal of playtesting, and jamming a lot of games, DO NOT cheat on the mulligans. Don’t do it. Your data will be far better in the long run if you mulligan properly. Only mulligan the sneaky way if you are short on time and resources, and even then, recognize that you are probably impacting your results. Whichever way you’re mulliganing, you should have both decks do the same thing. Doing it without a proper balance will definitely affect your results.

One thing that can also be useful is “cheating” on opening hands. So, you think that having a Wrath of God in your opening hand matters? Start your hand with Wrath of God and five random spells (like a mulligan), every game for a testing session. You can measure the impact of what happens when you would get the mulligan you are looking for. Or, just measure six card hands as compared to your seven card hand. How bad is mulliganing for your deck. You’ll find that knowing just how bad a mulligan is for a particular deck is incredibly valuable information.

Real Cards / Proxies

Anyone that knows me knows that I am the king of proxies (or at least a king of proxies). It can be incredibly useful to playtest with proxies, if only because of the economic benefits (to say nothing of the preparation time). There are some real problems to proxies, though.

I forget if it is Chris Pikula or Jon Finkel that was the more famous anti-proxy proponent. Whichever the case may be, the essential critique is simple. Proxies cause you to go through an extra interpretive step in your play. You look at your proxy, and depending on what exactly it is, your brain (and your opponent’s) has to do some thinking about what it is that is in your hand. When you aren’t playing with proxies, you can think more closely to the game state itself.

Proxies cause mistakes as well. The simple rule that I have with proxies is this: the more serious you are about your deck, the more real cards you should be playtesting with. If your opponent forgets that your Tarox is actually a Siege-Gang Commander, for even a moment, they can make a wrong call. Even on your own end, it can cause a chain of events, like the mistapping of land, which in turn causes the opponent to make a different play, which in turn moves the game in an entirely different path.

Sideboards and Shortcuts

There are probably an infinite variety of shortcuts that we can employ. Well, okay, not an infinite variety, but at least a goodly amount. The thing to remember is that there is a give and take with any shortcut. Any playtesting shortcut will give you a return in time. And it will take with it a degree of accuracy.

The most common way that Magic players play out matches is the ten-set. They play ten games, and that is their matchup result. This is probably the most classic shortcut. Anything less than 50/50 in their matchup of choice is usually viewed as a death knell, a reason to abandon ship. Never matter than a 40/60 matchup goes slightly above 50/50 if you can get even a 55/45 sideboarded result.

If we really want to get the best measurements, we really do need to test with sideboards. Even a 30% win percentage game 1 can shift into the positive with only a 60% sideboarded. But most of us shortcut the sideboard, and don’t really particularly measure it.

Why do we take shortcuts? Because doing things the right way takes time. Even Gerry Thompson, MTGO-man extraordinaire, takes shortcuts. We usually have to. Always, though, remember that if you have the time, take it.

They call this a “Firestarter,” right?

What kind of playtesting do you do? Do you have any particularly clever shortcuts (or long cuts)? What tricks do you have that you think make your Magic playtesting better? I’d love to hear about them.

Only two weeks until school is out for the summer for me, and only three weeks to Pro Tour. Whew! Wish me luck!

Shortcutfully yours,