The Flash Deck

By now, everyone who has been paying attention has seen the Flash deck. No sooner had I devoted some serious time and energy into the deck than almost identical variants started popping up on the information super highway. There are many, many ways to build Flash – and perhaps the best analysis of Flash variants should come in the Grand Prix Post-Mortem rather than before it. Instead, I’m going to explore the emergence of Flash into the Legacy metagame.

I decided that the best way to build Flash was to map out all possible configurations and figure out where they fell in terms of Speed and Resilience. Take this decklist, my fastest Flash list:

Creatures (11)

Lands (15)

Spells (34)

This maindeck had the fastest goldfishing rate of any Flash list I identified. More than that, it was the fastest deck I’ve ever seen, ever. In a twenty game run, sixteen of those games (alternating play and draw) won on turn 1. That’s a turn 1 goldfish of 80%. On the other hand, this deck has at least a 10-15% failure rate. By failure rate I mean something resembling a mulligan to five and a turn 4 goldfish for reasons that should be apparent.

The DCI banned Lion’s Eye Diamond and Burning Wish in Vintage after concluding that Long.dec had a 60% turn 1 goldfish rate. Granted, the Flash deck will probably be winning on turn 1 in actual tournament play about 20% to 25% of the time simply because you will be forced to interact, but in terms of the goldfish, this is even faster than Meandeck Tendrils.

Most importantly, a substantial amount of the time, if not most of the time, that you comboed on turn 1, it was without protection (despite having Duress, Daze, and Force of Will). That was the Meandeck Tendrils fallacy. Having a 66% turn 1 goldfish means very little if it collapses in the face of the mildest forms of resistance.

The obstacle I faced in tuning the Flash list was that I couldn’t simply cut one card and add another to determine if it becomes more or less fast or resilient. I’m going to explain why this is the case, but some important background information is necessary to lay the groundwork first.

Systems Theory and Magic (Particularly Legacy)

What makes Magic singularly unique among almost all strategic endeavors is its dynamism (perhaps even war – although I’m sure General Petraeus may disagree). Magic decks are part of a complex system we call “the metagame.” By “complex” I do not intend to signify the same meaning understood in everyday usage. “Complexity” here refers to the fact that Magic contains systems that have large numbers of internal elements. In Chess, there are only six types of pieces and only two colors. That doesn’t make Magic more complex than Chess in the commonsense use of the word, but Magic has far more variables.

In the past I’ve suggested that Magic metagames are in some important ways analogous to an economy, in terms of the complexity of the system and the various relationships of those internal elements. Metagames are constantly shifting and changing.

The emergence of the Flash deck offers critical insight into how complex systems can change, and do so rapidly. Typically, we may envision the metagame (much like an economy) as in a relatively constant state of change as preferences, knowledge, or technology changes over time.

However, complex systems can also experience rapid change. The introduction of a new element can serve as a catalyst for dramatic change. In systems theory, this is known as “positive” feedback. Policy makers in the political arena often attempt to improve the world around us by implementing measures designed to achieve a desired outcome. Too often, our efforts are not effective, or at least not to the extent we imagined. Part of the reason for this is that we are often trying to make changes in a complex system. When the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates, it is taking action designed to have repercussions throughout the entire economy (and hopefully stimulate economic growth). There are elements in the economy that will interact to produce outcomes that are beyond the Fed’s control.

When a particular action or input creates no real change in the system, that is known as “negative feedback” in systems theory lingo. You can think about it in terms of chemistry if that is helpful. Sometimes you mix together various ingredients and you have no chemical change – all you’ve done is swap them around, much like you make a salad. However, other times you can mix various chemicals together and get explosive reaction because the chemicals interact in a particular way that changes the chemical composition of the various parts. The former would be negative feedback, and the later would be positive feedback.

Magic metagames tend to change most frequently with the introduction of new sets and with restrictions or bannings. Add to that list, once again, errata.

The re-introduction of Flash into the Legacy metagame has created tremendous positive feedback. A metagame that was once understood as a stable mix of Goblins, Threshold, and various other decks has been wrenched into a cycle of dramatic change. I predict that the Legacy metagame, which was once going to be at least two-thirds aggro will now be predominantly blue based. I fully expect to see plenty of Meddling Mage decks in the Top 8.

But it is not simply that metagames are complex systems. Decks are complex systems as well. Each of the various parts has internal interactions that produce particular outcomes. For example, Fetchlands and Brainstorm interact in a particular way to help you see more cards of your library than you would without. Decks are also in flux, just as metagames are. One of the most common mistakes I see in Magic generally is the assumption that decks are static, followed by the conclusion that Deck A beats Deck B.

The importance of this observation brings me back to the discussion of the Flash deck regarding the trade-off between speed and resilience.

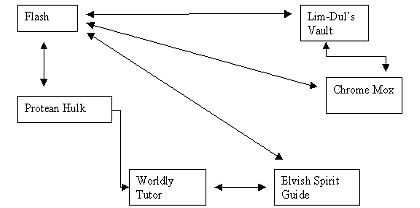

Take any given Flash deck. Goldfish it ten times, documenting its basic rate of speed and figuring out how much disruption you have when comboing out. This will give you a rough idea of its speed and resilience. Let’s say you cut two cards and add two other cards. Then you goldfish ten games again and you get new data. That sort of mapping is linear. You are cutting a few cards at a time. The problem is that in order to map out Magic speeds and resilience, you can’t simply make linear trade-offs. This is because of the fact that Magic decks have internal interactions. Often you will want to swap out whole chunks of cards to generate additional synergies. For instance, let’s say you cut Worldly Tutors for Lim-Dul’s Vault. You may find that the deck is now more resilient, but less powerful and slower. Then, you put the Worldly Tutors back in and then cut the Elvish Spirit Guides for Chrome Mox. Then you decide that Chrome Mox does nothing that Elvish Spirit Guide can’t do as well. What you have done is linear testing. Instead, you miss the fact that Chrome Mox and Lim-Dul’s Vault have positive interaction. If you cut both Worldly Tutor and Elvish Spirit Guide for both Chrome Mox and Lim-Dul’s Vault then you will get very different results than if you just cut one and tested it in isolation. Here is how you might view one small segment of the Flash decks internal interactions:

This graphic and this example begin to show you the incredible complexity of Magic decks: various components are paired.

My teammates inform me that this concept was evident in Affinity in Standard. You couldn’t analyze Shrapnel Blast or Somber Hoverguard alone, they had to be considered in the scope of everything else. You chose Atog or Shrapnel Blast usually, and that affected whether you ran Aether Vial or something else.

I’ve often used the analogy to Vintage Stax. The question of whether to include Chalice of the Void has a huge impact on the remaining card choices. Tangle Wire’s presence is often paired with Goblin Welder. Without Tangle Wire, Goblin Welder simply isn’t as worthy as a four-of. Without Welder, you are presumably running: 3-4 Sphere of Resistance, 1 Trinisphere, 3-4 Chalice of the Void, 3-4 Crucible of Worlds, and 4 Smokestack. Which of those cards are worth Welding or will need to be Welded in? Probably just the Trinisphere and the Smokestacks. But if you run Tangle Wire, then suddenly Welder becomes a lot better. In addition, if you run Tangle Wire and Goblin Welder, there simply isn’t room for Chalice of the Void unless you start cutting into the meat of the deck.

It is intuitive to Magic players that cards have synergies, but is it intuitive that testing regimes need essentially work on three dimensions? That is, you can’t just “tweak” decks to map out all the various configurations of speed and resilience, but you have to consider internal synergies of cards you aren’t running as well. This gets to the very heart of what I mean by Complexity. It is not simply that you want to map out how the addition of Lim-Dul’s Vault will interact with the cards already in your deck, but you want to also consider how the various cards not in your deck might make the addition of Lim-Dul’s Vault more effective.

Elvish Spirit Guide works very well with Worldly Tutor but less so with Lim-Dul’s Vault. There is clearly a trade-off between the two, but in terms of deck design, it isn’t a linear relationship. That is, cutting some cards and adding others don’t make your deck slower and less resilient, often times the internal components (the various cards) are “paired.” Now look back up at the graphic I constructed and you’ll see that I have mapped out those relationships.

Vintage Lite

Magic metagames as dynamic systems are amazing to watch. The introduction of Flash transformed the whole Legacy paradigm. The result has been quite astounding: every deck in Legacy is moving to interact on the first turn. Some players seem to find this notion “offensive.” But the reality is that those decks that don’t interact or have the capacity to interact on turn one are disappearing from the metagame. Thus, decks like Rifter, Affinity, and Burn are going away very quickly (note that Affinity can run Force of Will and even Cabal Therapy). Goblin Lackey on turn 1 isn’t interactive. It does nothing to the opponent on turn 1. I’m talking, primarily, about these cards:

Force of Will

Daze

Stifle

Duress

Cabal Therapy

Extirpate

Leyline of the Void

In other words, Legacy is becoming Vintage without the breadth of cards. Every single deck in Vintage is designed to interact from the beginning of the game. It’s the only way to survive. The difference is that cards like Mishra’s Workshop and the power of Null Rod / Chalice of the Void provide more ways to interact. (Note that Chalice of the Void will be much stronger post Future Sight in stopping Summoner’s Pact and Pact of Negation). Mishra’s Workshop can easily power our turn 1 Trinisphere in Vintage. In Legacy, most decks are restricted to one land on turn 1, with the exception of a Spirit Guide or Lotus Petal or Dark Ritual.

And yet, this is probably to be expected. In Legacy a litany of combo decks are possible, from IGGy Pop to R/G Belcher to Aluren to Flash. It’s not unreasonable to demand that most decks interact. It’s simply the law of large numbers. Given a card pool big enough, decks will accelerate not simply because of mana acceleration, but because there are more combination of cards that could potentially just win the game without having to rely on creatures in the traditional way.

The Flash deck is very beatable. From what I’ve seen so far, the Fish variants seem to have the best matchup, followed by Madness and Landstill. Threshold seems to have an unfavorable match, but still winnable. Goblins, of course, is annihilated.

I’ll be honest: I love it. I think the Grand Prix is going to be a lot of fun. Classic Vintage type interactions: Turn 1 Brainstorm, Fetchland, Duress, Force of Will. So many insane plays. The Grand Prix’s transformation should actually give most players a window into Vintage. It may seem broken (and it is), but it’s actually fair in some counterintuitive ways.

Flash may be broken, but in some ways it’s actually made Legacy more interactive. Goblins can combo out on turn 3 or 4, but it just goldfishes over you. Most of the decks in Legacy, even the combo decks, play plenty of interactive cards to protect and shield their combo. Look at my Speed Flash deck. It has twelve disruption spells.

People are arguing that Flash will get banned, and perhaps it should be. Perhaps it shouldn’t. But one of the key arguments that people offer in support of banning is that Flash will be even more broken with Future Sight legal. That may be true in one sense. But it is also true that it will be more vulnerable. Chalice of the Void will take out no less than twelve cards out of the deck when played for zero (4 Pact of Negation, 4 Summoner’s Pact, and 4 Lotus Petal). That’s nearly a fourth of the deck.

The big remaining question is: once a system has been transformed – once a complex system has been reconfigured by the introduction of a radical new element, will the removal of that element undo the transformation? Can the genie be put back in the bottle with one banning? I’m willing to bet not. Even if Flash goes away, I think that there are other insane combos waiting in the wings that will keep Daze, Stifle, and Duress around and Goblins at the margin. Only time will tell. Enjoy yourself at Grand Prix: Columbus. Introduce yourself if you happen to see me. I should be wearing a blue “Mean Deck” t-shirt.

Until next time,