Last week, we explored the problem of a Mana Drain dominated format.

To recap, this was the problem:

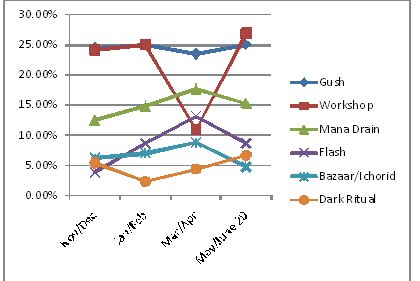

Mana Drain decks are dominating Vintage beyond not only their historical levels, but beyond what any other engine has been able to do in modern Vintage. The DCI restrict a bunch of cards last June purportedly to rebalance Force of Will decks against the other pillars of the format. Instead, they took a relatively diverse format, this:

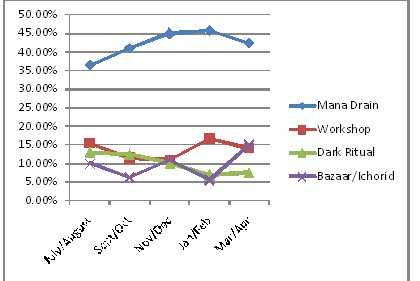

And turned it into this:

To see the full picture, take a look at this link of both trend lines together.

Last week I explored the possibility of restricting Thirst For Knowledge to weaken Mana Drain decks a little, and allow other archetypes an opportunity to compete more effectively. Thirst For Knowledge is currently the third most commonly played spell in Vintage Top 8s, after Force of Will and Mana Drain. Restricting Thirst would force Mana Drain decks to adopt a different, less powerful draw engine, or rely entirely on singletons draw spells to support itself. This should weaken Drain decks slightly (at a minimum) and allow other decks a little bit more breathing room.

However, there is more than one way to skin a cat. If the same objective can be achieved through unrestriction, then that option should also be considered. As a general rule, Vintage players dislike restrictions since they take away existing deckbuilding options. Additionally, restrictions enlarge the restricted list and increase the number of singletons that the remaining decks will be compelled to include. As a policy devise, over-use of restriction could lead to a critical mass on the restricted list, where deck design becomes less flexible, not more. As a policy alternative, unrestriction avoids these pitfalls. Beyond simply giving existing decks a leg-up on the competition, they also have the potential to inject new archetypes into the metagame as well, particularly if they are targeted and well-designed.

Today, I will explore a bunch of possible unrestrictions, many of them controversial. I ask that you consider them with an open mind, as I have.

But before I begin, let me lay the groundwork for thinking about restricted list policy.

The Metagame As Complex System and Restriction as a Transformative Intervention

I have written that Magic metagames are complex adaptive systems. A single printing, much like a single restriction, has the power to transform these metagames. The printing of Painter’s Servant last year dramatically illustrates this. Painter’s Servant created a new home for the Gush-Bond Engine, and one that was incredibly effective at beating the two best decks in the format: Flash and Tyrant Oath. Subsequently, Flash and Tyrant Oath dipped in performance, and an archetype that was successful at attacking Painter decks climbed to the top: Workshop decks. A single printing changed an entire metagame system. It wasn’t just the immediate effects that mattered, there were secondary and tertiary effects.

By the same token, restrictions that are designed to neuter a major archetype necessarily have the effect of transforming the existing metagame in the same way, but in reverse. This is actually the flaw in overbroad restrictions. In the past, the DCI has attempted to neuter decks not with a single restriction, but with a wave of restrictions. Each and every time it has conducted its restriction policy in this manner, it has later proved overbroad by unnecessarily restricting some cards.

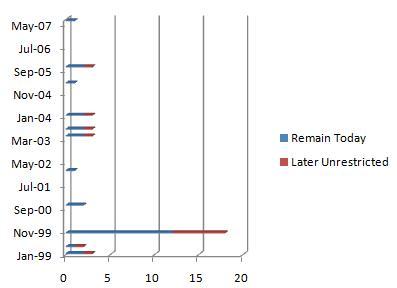

In one tsunami wave of restrictions, the DCI restricted eighteen cards on October 1, 1999:

Crop Rotation, Doomsday, Dream Halls, Enlightened Tutor, Frantic Search, Grim Monolith, Hurkyl’s Recall, Lotus Petal, Mana Crypt, Mana Vault, Mind Over Matter, Mox Diamond, Mystical Tutor, Tinker, Vampiric Tutor, Voltaic Key, Yawgmoth’s Bargain, and Yawgmoth’s Will

While the restricted list needed to be modernized, the manner in which they did it left much to be desired. Even at that time, their objective of neutering fast combo could have easily been accomplished without such overbreadth. They could have restricted half that many cards and still produced the same result. Since then, a full third of those restrictions have been reversed (Doomsday, Dream Halls, Hurkyl’s Recall, Mind Over Matter, Mox Diamond, and Voltaic Key). It took nine years for them to unrestrict trash like Dream Halls, and there is still more detritus on there. Grim Monolith, for example, has no business being on the restricted list. It is debatable whether Enlightened Tutor and Frantic Search should be there too.

Perhaps the DCI was frustrated. Earlier in the year, in two separate announcements, it restricted Stroke of Genius, Tolarian Academy, Windfall, Memory Jar, and Time Spiral.

In 2003, the DCI restricted both Lion’s Eye Diamond, Burning Wish and Chrome Mox to neuter Storm Combo. It really only needed to restrict Lion’s Eye Diamond to accomplish its objective. The decision on Chrome Mox was reversed six months ago. Burning Wish remains unnecessarily trapped on the Restricted list.

Then, last June, the DCI restricted five cards: Merchant Scroll, Brainstorm, Ponder, Gush, and Flash. At a minimum, it is apparent that neither Gush nor Flash needs to be restricted with Merchant Scroll, Brainstorm, and Ponder all restricted. Flash was so fearsome precisely because of Merchant Scroll, for a reliable tutor engine, and Brainstorm, to help it assemble the combo and counter-protection, and to help it trade creature combo parts for business. This was how Flash was able to survive in a field where everyone ran Leyline of the Void in their sideboard. With Brainstorm and Scroll restricted, Flash is far too slow, vulnerable, and inconsistent to even contemplate restricting. Also, the Gush-bond engine was killed by restricting Scroll and Brainstorm alone.

Take a look at this graph, which illustrates every single restriction since 1997:

Every single time the DCI restricted more than 1 card that was previously unbanned and unrestricted since 1997, it later reversed either half to a third of those decisions, with the sole exception of the September, 2000 restrictions, both of which remain today (Demonic Consultation and Necropotence). In total, they have undone 1/3 of the restrictions made since 1999, not counting the restrictions last June.

This should not be surprising. In light of our understanding of Magic metagames as complex systems, a single targeted restriction can easily produce the desired result on account of a single card’s interaction with other cards. When the DCI restricts more than one card, it is virtually a guarantee (based on the last decade) that the DCI will later reverse some of those decisions. When the DCI restricted Trinisphere, it could have restricted MIshra’s Workshop and Crucible of Worlds as well, the unholy trifecta. Yet, the restriction of Trinisphere lessened the need to restrict the other two cards, and they didn’t.

Unfortunately, the DCI doesn’t always think that way. They have an unfortunate pattern of trying to restrict multiple cards at once. This is a bad habit, with negative consequences.

Had the DCI simply restricted Merchant Scroll last June, it could have accomplished at least half of what it desired, since Merchant Scroll was the card that not only fueled the Gush-Bond engine, and gave it its most powerful tutor, draw engine, and source of resilience, but also Flash and Gifts decks for the same reason. Had the DCI restricted Merchant Scroll in 2007 instead of Gifts, none of these restrictions would have been as likely.

With these two ideas in mind: that the metagames are complex systems and the restricted list policy can best be viewed as an intervention into the system that will inevitably change system outcomes, we can see that the solution to the problem articulated last week may well be resolved by targeted unrestrictions. However, for the same reasons that restrictions should happen piecemeal, it also means that unrestrictions intended to ‘shake up’ the format should also happen, ideally, one at a time. Each unrestriction, especially if it is well-targeted, will have its own immediate impact and then feedback loops. I believe that all restrictions and unrestrictions should therefore happen one at a time, or at most in pairs of 2, and no more.

My goal is to identify possible unrestrictions that meet these criteria:

1) Would have an impact on the metagame

2) Would be find a most suitable home in a non-Mana Drain shell.

3) Would help generate metagame diversity.

Cards like Grim Monolith have no place on the restricted list, but they would serve no metagame purpose, since it would have zero impact on the format. The most terrifying use of Grim Monolith, a mana accelerant that is inferior to Cabal Ritual and Elvish Spirit Guide, let alone Dark Ritual, would be in the home of a Belcher deck or a Power Artifact combo, both of which seem very tame by today’s Vintage standards.

The most important element is (2). The unfortunate reality is that given a choice between a Mana Drain shell and a non-Mana Drain shell, most Vintage victory conditions find superior homes with Mana Drains. Game theory suggests that archetypes that are difficult to hate out are strategically optimal. Unlike its competitors, Drain decks are far more resilient. They both fuel their major engines, like Gifts, Thirst, and myriad broken restricted cards like Yawg Will, Tinker, and Time Vault, but they protect them. Dark Ritual does not protect itself. That’s why Workshops, Bazaars, and Ritual decks are much easier to answer with single card tactics like Hurkyl’s Recall, Tormod’s Crypt, and Sphere of Resistance. No single printing would be as effective as hosing Drains as printings may do for addressing other engines. In some ways, Drains are worse than the Gush-Bond Engine, since it creates homogeneity for precisely the same reason. The Gush-Bond engine was so dominant because it was the best draw engine you could run, and it was easy to port. Likewise, Drains are often the best engine you can run, and since so many win conditions in Vintage are playable in Drain shells, Drain decks become the dominant engine.

It is critical, therefore, that we look for cards that would create a competitive rival with Mana Drain archetypes rather than boost Mana Drain decks, a difficult task, but not an impossible one.

Channel is one of the more interesting possibilities. For many years, Mind Twist and Channel were the only two non-Ante cards banned in Vintage. Together they sat until the DCI decided, in 2000, that there would no cards banned for power reasons in the format. Thus, Channel and Mind Twist were unbanned and simultaneously restricted.

In considering its potential if it were to be unrestricted, there are three salient features to Channel that need to be mentioned at the outset:

1) Channel is not a card that would boost Mana Drains.

2) Channel is a highly conditional card, similar, although not to the same degree, as Flash.(which I’ll say more about later).

3) At a minimum, Channel is not a problem unless it can muster a consistent turn one kill.

Let me address each in reverse order. Channel is part of one of the most famous Magic kills in history: Channel Fireball. This legendary kill was so fearsome that it led to Channel’s eventual banning from ‘Type 1′ in 1995. While such kills are hardly fearsome today, there is cause for concern if a Vintage deck can muster a certain threshold kill on turn one. Let me explain.

Just as Einstein understood that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, there is a fundamental limit on how fast you can make a two card combo in Vintage, even if every single Vintage card were unrestricted. That limit is roughly 70-80% turn one goldfish. With a fat restricted list of 40-50 cards, that number is much lower. Why? This is a function of two rules of deck construction: a maximum of 4 unique cards per deck and a 60 card minimum. The intersection of these two rules creates fundamental limits on what can be achieved.

In an experiment I conducted last fall, I tried to see what might happen if there was no restricted list. Even in a deck with 4 Black Lotuses and 4 Mox Sapphires, etc., there was a fundamental limit on how fast I could make most of the decks I designed. For example, my unrestricted Flash deck could not get much faster than a 75% turn one goldfish. Even my first attempt at unrestricted Mind’s Desire deck was only a 70% turn one goldfish.

If a deck with 4 Channels cannot achieve anything faster than a 25% turn one goldfish, then I would say it is presumptively fair (I will address the ‘fun’ question later). Why?

First of all, just as there is a fundamental speed limit in Magic due to the two fundamental rules of deck construction, there is a fundamental trade off in Magic between speed and consistency and resilience. This principle can be found throughout deck design, and not simply in Vintage. The faster you make a deck, the more vulnerable you make it to certain strategies. Thus, in my Unrestricted Vintage experiment, the deck with the 100% turn one Goldfish was not necessarily the best deck. If Channel can’t even achieve a 25% goldfish, then three factors come into play:

1) Your goldfish rate is far less than the chance of your opponent drawing Force of Will, which means that in terms of playing War, you are likely to lose more than you win. In my view, the turn one goldfish has to be at least 40% or higher before we start becoming very concerned in Vintage.

2) 75% of the time you will be giving your opponent at least one turn. In a format where not just like Misdirection, Force of Will, and Commandeer are seeing lots of play (i.e. the cards that can stop you on the play), but where Duress, Chalice, Thoughtseize, Mystic Remora, Null Rod, Sphere of Resistance, Thorn of Amethyst, Unmask, Cabal Therapy, Pithing Needle, etc. all see plenty of play, then it is unlikely that you will be able to go off on turn one with any reliability if you are on the draw.

3) 37.5% of the time, you will be giving your opponents two turns, which means that a much, much larger percentage of cards become relevant, from things like Gaddock Teeg, Mana Drain, and Ethersworn Canonist upward. Not to mention the fact that Ichorid, TPS, and Dragon could combo kill you before the 4 Channel deck gets a 2nd turn.

If Channel is not capable of generating a fairly consistent turn one kill, then even if it is unfun, it is presumptively fair. Every turn that Channel decks wait to ‘go off’, they give their opponents more time to interact.

The second point I wanted to explain is that Channel is a very conditional card. At a minimum, the requirements for a successful Channel deck are:

1) A way to consistently play Channel

2) A use for egregious amounts of mana

The first condition is actually more critical than you might think. First of all, you cannot use Fetchlands to find your green mana source, since you’ll likely need that additional life if you intend to use Banefire or other X spells as a win condition. Secondly, there are a limited number of unrestricted ways to generate green on turn one (especially without Fetchlands):

1) Dual lands/Rainbow lands

2) Forests

3) Elvish Spirit Guide

4) Chrome Mox

5) Mox Diamond

6) Manamorphose

7) Chromatic Star/Sphere effects

8) Land Grant

9) Summoner’s Pact for Elvish Spirit Guide

And restricted sources:

10) Mox Emerald

11) Lotus Petal

12) Black Lotus

Realistically, any deck that wants to play Belcher on turn one will need to run many of the first 9 items and all of the remaining options. If they don’t, then you aren’t looking at an appreciable turn one goldfish percentage. Many of these cards are bad or very narrow. The use of these cards means that you are already playing a potentially vulnerable or inconsistent archetype.

The final point I made was that Channel is not a card that is very good with Mana Drains, a prerequisite to this project. Mana Drains do not fuel Channel, nor would they very nicely support Channel, for many reasons so obvious I need not delve into them.

With these thoughts in mind, I elicited the advice of many Belcher players, including my friend Nat Moes, for suggestions on how to build a 4 Channel Belcher. Here is what Nat came up with:

RGu 4Chan Belcher

4 Goblin Charbelcher

3 Lich’s Mirror

1 Kaervek’s Torch (or whatever)

1 Memory Jar

1 Wheel of Fortune

1 Tinker

1 Timetwister

4 Channel

4 Manamorphose

4 Elvish Spirit Guide

4 Simian Spirit Guide

4 Tinder Wall

4 Rite of Flame

4 Chrome Mox

4 Summoner’s Pact

5 Moxen

1 Black Lotus

1 Lion’s Eye Diamond

1 Lotus Petal

1 Mana Crypt

1 Mana Vault

1 Sol Ring

4 Guttural Response

1 Pact of Negation

Shortly after I requested that Nat show me what 4 Channel Belcher might look like, I decided to try my own hand at designing such a monstrosity.

Here is the fastest Channel list I’ve come up with:

4-Channel Belcher

Stephen Menendian

4 Serum Powder

4 Goblin Charbelcher

4 Banefire

4 Lich’s Mirror

1 Wheel of Fortune

1 Memory Jar

4 Pact of Negation

2 Guttural Response

4 Chrome Mox

4 Channel

4 Elvish Spirit Guide

4 Simian Spirit Guide

4 Tinder Wall

4 Manamorphose

1 Lion’s Eye Diamond

1 Grim Monolith

1 Mana Crypt

1 Mana Vault

1 Black Lotus

1 Sol Ring

1 Lotus Petal

1 Mox Ruby

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Sapphire

1 Mox Jet

1 Mox Pearl

Some notes about the design:

Nat overlooked Serum Powder, which is odd because it is a card he has favored before. Serum Powder is an absolute necessity in a deck like this, since it dramatically increases the range of viable opening hands.

I chose two win conditions: Goblin Charbelcher and Banefire. Lich’s Mirror is the deck’s backup engine. What I discovered was that Land Grant was awful, since although it made it easier to be able to play turn one Channel, it dramatically increased the chances that you fail to win on turn one.

Pact of Negation was included for primary protection, and it works well with Lich’s Mirror as a bonus. Guttural Response got the nod over Red Elemental Blast or Pyroblast because of the importance of imprinting it on a Chrome Mox. To be honest, one of the biggest limitations on this deck was not just finding Channel (which Lich’s Mirror and Banefire were both conditioned upon), but rather being able to play it. I had not thought of Summoner’s Pact when I designed this deck. I would probably include four if I were to goldfish this again.

I threw this deck together to test the goldfish speed against the litmus test I set out above. If you recall, anything under 25% of turn one goldfish I decided was presumptively fair. But anything above the probability of seeing a Force of Will in an opening hand, around 40%, is presumptively unfair.

What did I discover?

After 30 goldfishes, in ten game sets, I was very surprised to discover:

13 Turn 1 Kills (5 with Protection)

5 Turn 2 Kills

12 Stalls (mull to oblivion)

At a goldfish clip, this deck had 43.3% turn one goldfish. Serum Powder was probably the biggest reason behind that fact, as Serum Powder was used in over half of the goldfishes. Since I was aggressively mulliganing to try and push for a turn one goldfish, the “stall” rate probably overstates this decks complete failure rate. I imagine that playing with Summoner’s Pacts makes this deck even faster.

Given the high turn one goldfish rate, I do not support unrestricting Channel. Vintage already suffers from a reputation for having turn one kills, and I would not want to contribute to that perception. Secondly, such a high goldfish rate would undoubtedly be considered “unfun.” Lion’s Eye Diamond and Flash were both cited as restrictions based more on speed than tournament dominance, per se. Trinisphere was explicitly restriction on account of the fun factor. Given this goldfish clip, I doubt that 4 Channel Belcher would survive on that account either.

However, on the unfun issue, it is hard to see how Channel would be less unfun than Flash, from a thematic and mechanical perspective. The cards that would be used in a Channel deck would be unlike anything currently used in Vintage, from the “Johnny” Lich’s Mirror to the “Timmy” Banefire. I could imagine many players having a blast playing with Channel.

But even if the deck were unfun, an argument could be made that it is fair, despite the presumption against it on account of its goldfish rate. The next question is whether this deck is likely or even capable of winning tournaments. If a deck has a high turn one kill, but is functionally incapable of winning tournaments (because, let’s say, the times in which it doesn’t have a turn one kill it fizzles out), then it should not be restricted on fairness grounds alone. That’s the difference between the three other restrictions I just mentioned. Although Flash, Lion’s Eye Diamond and Trinisphere were cited for their turn one ‘kills’ as part of the reason they were restricted, those decks were all capable of winning tournaments, and even did so with varying degrees of frequency.

So, the real question is how well Channel would do in the matrix of turn one kill frequency and tournament viability/performance. A very high rating on either one but a very low rating on the other would not be sufficient to be concerned. However, a mid-grade rating on either might justify concerns. It just depends on where we draw those lines.

My intuition — and this is not based on any data — is that this is not a deck that would be capable of winning tournaments of 33-or-more players, but it would be a deck that could Top 8. My guess is that this deck would come out of the gate somewhere between 2-6% of Top 8s, and stabilize somewhere below Ichorid, which often varies from 5-15% of Top 8s.

My final verdict: Do not unrestrict on account of its speed.

Like Channel, Flash is a highly conditional card. Most obviously, Flash requires a combo component to function: Protean Hulk. However, Flash also shapes your deck choice in very limiting ways. You have to include a certain number of combo parts, which limit what else you could include. Third, unlike Channel, Flash is ‘stone kold’ to Leyline of the Void, which used to be an omnipresent and multi-threat answer to both Flash and Ichorid. With Ichorid’s numbers on the rise, Leyline is likely to see more and more play. With Leyline in Play, Flash becomes a 3 card combo, where all three cards must be assembled in order to win.

Here is what Flash looked like pre-restriction (taken from the final SCG P9 Top 8 before the June 20 restrictions):

3 Flooded Strand

3 Polluted Delta

2 Tropical Island

2 Underground Sea

2 Island

1 Black Lotus

1 Lotus Petal

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Jet

1 Mox Pearl

1 Mox Ruby

1 Mox Sapphire

4 Protean Hulk

1 Body Double

1 Carrion Feeder

1 Reveillark

1 Mogg Fanatic

1 Body Snatcher

4 Force of Will

4 Brainstorm

4 Pact of Negation

4 Flash

4 Merchant Scroll

2 Summoner’s Pact

2 Ponder

2 Thoughtseize

1 Mystical Tutor

1 Misdirection

1 Chain of Vapor

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Vampiric Tutor

As you can see, the core of the deck was Merchant Scroll and Brainstorm. Patrick and I both agreed that this deck would prefer 3, and even 2 Brainstorms, to having Ancestral Recall, if that were the Hobson’s Choice. With Brainstorm, Merchant Scroll, and Ponder restricted, this deck not only loses its ability to combo out with any degree of consistency and speed, but perhaps more importantly, it loses the ability to answer cards like Leyline and mold its hand to protect its combo kill. Both Brainstorm and Scroll not only dug for the combo parts, they also helped the deck assemble protection.

Without those cards, or even a substitute in Ponder, here is what Flash might look like today:

Post-Restriction Flash

3 Flooded Strand

4 Polluted Delta

2 Tropical Island

2 Underground Sea

2 Island

1 Black Lotus

1 Lotus Petal

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Jet

1 Mox Pearl

1 Mox Ruby

1 Mox Sapphire

4 Protean Hulk

1 Body Double

1 Carrion Feeder

1 Reveillark

1 Mogg Fanatic

1 Body Snatcher

4 Force of Will

1 Brainstorm

2 Sensei’s Divining Top

4 Pact of Negation

4 Flash

1 Merchant Scroll

3 Summoner’s Pact

1 Ponder

2 Duress

2 Thoughtseize

1 Mystical Tutor

1 Misdirection

1 Chain of Vapor

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Imperial Seal

Changes:

– 3 Merchant Scroll

– 3 Brainstorm

– 1 Ponder

+ 1 Polluted Delta

+ 1 Summoner’s Pact

+ 2 Duress

+ 1 Imperial Seal

+ 2 Sensei’s Divining Top

My personal view is that if Flash were legal today it would be a tier two, at best, competitor, and probably much worse. To be perfectly honest, once the novelty wore off again, I would expect Flash to settle down below 5% of Top 8s, below the point at which we even take notice.

This deck is actually pretty bad. And it gets worse if your opponents start to run Leylines. One of the biggest problems is that if you draw any two non-Hulk creature cards, you can’t win unless you can hard cast them. Also, cards like Summoner’s Pact and Protean Hulk begin to accumulate in your hand and there are no Brainstorms around to trade them for usable spells.

With respect to the three conditions I set out at the beginning of the article, I think Flash would have a very marginal metagame impact, but help create more diversity in the format without helping Mana Drains.

Final Verdict: Modestly in favor of unrestriction as a means to combat Drains, since it really wouldn’t be that effective on that front, but fully support its unrestriction on the principle that it is an unnecessary restriction (similar to Grim Monolith).

In light of its prominent position in many of the best decks from the last couple of years, Gush is a much feared card. In addition, the ability to generate card advantage at no mana cost was an effect that allowed Gush decks to supercede slower Mana Drain decks in the metagame, and reshaped the metagame in the process.

However, Gush is badly misunderstood.

Gush saw little play from the time it was printed in 1999 until Planeshift. It was used as a combo engine in janky ‘turboland’ decks, but it was otherwise a fringe player. In February, 2001, Quirion Dryad was printed in Planeshift, and suddenly “Grow” decks, using a bunch of cantrips and Gush as a draw engine emerged onto the scene and became a metagame competitor, a port from Extended. The “Grow” concept was simple: build a light mana base with plenty of cantrips to compensate for the lack of actual land. This way you create virtual card advantage, enjoy better topdecks, and win counterwars.

Then, in the fall of 2002, Onslaught was printed, and with it came fetchlands. This revolutionized the format, and Grow decks were no exception. With Fetchlands, you could realistically preserve the advantage of Grow (a light mana base with lots of cantrips and counterpower), but graft it onto a three-or even four-color manabase! Suddenly, you could play cards like Yawgmoth’s Will and Psychatog with Gush, and Gush became an engine that didn’t just support a fair Aggro-Control deck that preyed upon slow control decks, but a monstrosity that could play all three roles simultaneously, aggro, control, with a combo finish. Then, the printing of Ponder in Lorwyn gave the Gush-Bond engine the final push it needed. Gush decks could now run 4 Gush, 4 Merchant Scroll, 4 Ponder, and 4 Brainstorm and reliably combo out from Fastbond to Yawgmoth’s Will as soon as it could tutor up Fastbond. This engine was so powerful because Scroll could find you Gush, Ancestral Recall or Force, and each Gush, Brainstorm, and Ponder would draw you into more of the same, but also because it was so flexible and dynamic. Although it was a straight beeline from Fastbond to victory, it was also a non-linear engine that could answer almost anything.

The restriction of Merchant Scroll would have seriously handicapped all Gush decks. At a minimum, the ability to no longer combo out in a single turn by chaining Gushes into more Gushes via Scroll meant that Storm decks could no longer use the Gush-bond engine. But the restriction of Brainstorm (let alone Ponder) cut deep into the heart of the very advantages that Grow decks were built upon. The drawback of having to bounce your own lands was offset by the cantrip ability of being able to dig for business and land with Brainstorm, Ponder, and Merchant Scroll. With those cards restricted, Gush went from being the integral part of a multi-card engine to presumptively unplayable. Beyond the destruction of the omnipresence “Gush-Bond engine,” Gush faces two more problems. Without Brainstorm and Ponder there is no way to reliably manipulate a very light manabase, the fundamental principle behind the “Grow” concept. You have to turn to much inferior substitutes like Sleight of Hand or Serum Visions. But equally important, without Merchant Scroll, Gush decks lose a lot of resilience and power that comes from being able to tutor up Force to counter an impending threat, a bounce spell to remove an annoying answer, or Ancestral Recall to generate an early burst of card advantage. In light of all of these losses, it made almost no sense for Gush to be restricted if the other three Gush-Bond engine cards were restricted as well.

Gush decks have lost the vast majority of the advantages that made them so powerful. Players miss this when they look at Gush in isolation, rather than in context. They contemplate how powerful Gush was as part of the engine, and therefore, wrongly, conclude that Gush would be too powerful today. What they overlook is that Gush is not nearly as powerful without those other cards; it is a pale shadow of its former power. This is part of the problem I elaborated upon in my article “Understanding Magic,” that Magic cards do not exist in isolation, but derive their power from synergies and context. In a context without Brainstorm unrestricted, Gush loses the very advantage that made Grow “tick.” With those cards gone, it is not feasible to combo out with the consistency that Gush decks used to have. Instead, Gush has returned to its original function, a nice, but slow, draw engine for Aggro-Control decks.

If Gush were unrestricted, here is how I would build a reconstituted GroAtog:

GroAtog with 4 Gush

4 Force of Will

2 Mana Drain

4 Duress

4 Thoughtseize

2 Misdirection

4 Sleight of Hand

4 Gush

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Brainstorm

1 Ponder

4 Quirion Dryad

1 Tendrils of Agony

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Mystical Tutor

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Imperial Seal

1 Merchant Scroll

1 Fastbond

1 Regrowth

1 Yawgmoth’s Will

4 Polluted Delta

3 Flooded Strand

4 Underground Sea

2 Tropical Island

1 Island

1 Mox Sapphire

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Jet

1 Black Lotus

Sideboard:

3 Island

2 Hurkyl’s Recall

1 Rebuild

2 Seal of Primoridum

3 Yixlid Jailer

2 Pithing Needle

2 Tormod’s Crypt

The attractiveness of unrestricting Gush is that it could provide a perfect metagame competitor for Mana Drain decks, without much hurting anything else. In fact, that is precisely the function of Gush decks! Gush decks are the perfect foil to Mana Drains. They allow Aggro-Control decks to win counterwars against their more powerful Mana Drain opponents. With Scroll, Brainstorm, and Ponder restricted, I believe that only a small number of players would switch from Drains to Grow with 4 Gush, but enough would to matter. Moreover, as we know from the last year and a half, the better Gush decks perform, the better Workshops perform.

We have seen from the past that over-broad restrictions require reversals later on. Gush is the most obvious unrestriction from the restrictions last year. It’s fair and a card that would achieve the objective set out: produce greater metagame diversity and engine balance. Keep in mind that Mana Drain decks would still have a powerful counter-answer in Mystic Remora, since Gush decks would still play multiple spells per turn.

A deck like this would be the perfect tool to compete with Tezzeret and Mana Drain decks. If it were strong enough, and I predict that it would produce a small, but devoted following of probably 5%, but below 10% of players, it would influence the metagame in positive ways. It would increase the diversity in the format, help combat Drain decks, and provide a small boost to Gush predators such as Workshop decks. Importantly, unlike in the past, the one key factor that would keep Gush decks a small portion of the metagame is the limited number of homes for it. Without Scroll, Brainstorm, and Ponder, Gush would only be playable in a very narrow set of decks, a critical difference from the past.

My Final Verdict: Recommend Unrestricting to help Combat Drains

Balance is by far the most difficult card to analyze, and potentially even more interesting than Channel. There are a number of reasons for this. First of all, unlike Gush or Flash, we have no experience in almost 15 years with what it is like playing with unrestricted Balance. Balance was restricted in April, 1995 after Adam Maysonet created the infamous Balance-Rack deck. Notably, that deck used Bazaar of Baghdad as an engine. I ran that deck in my notorious “Battle of the Banned” deck tournament a few years ago, and it was the most awful garbage in that tournament. Secondly, even though Channel is a similar boat, it is much more susceptible to analysis since the parameters for what might be fair are easier to delineate. The conditions under which Channel may be broken or even playable are much clearer.

Balance is a card that elicits many fears, and memories, on account of its fearsome power and efficiency. Many players, including some still residing at the DCI, probably consider Balance to be among the most powerful effects ever printed. However, abstract power cannot be the end, or even the beginning of the conversation. Vintage has a structure, which is made up of the various prominent interactions in the format. Regardless of how powerful Balance may be in some abstract sense, the only question that matters is whether the structure of modern Vintage is more or less vulnerable or resilient to Balance. As a point of comparison, ancient Type One was very susceptible to Mind Twist, which is why Mind Twist was banned, not simply restricted (something Balance never experienced). In the past, effects like Mind Twist and Balance were so devastating because they were incredibly difficult to recover from and easy to play. Yet, two years of unrestricted Mind Twist have demonstrated that once damaging effects can be inert or harmless in modern Vintage, or even modern Magic. In fact, Mind Twist seems almost no play in Vintage today, and it is generally acknowledged that Duress is a more powerful card. It’s not just that Mind Twist is inefficient, but its effect is not that damaging. It doesn’t hurt very much and it’s easy to recover from.

Balance is just as efficient as it was in the past, but like Mind Twist, it is far easier to recover from today than it was in the past. Even with Brainstorm and Ponder restricted, Vintage decks are designed for maximum efficiency and topdecking power. Vintage decks operate on minimal mana requirements, and run enormously powerful recovery effects, such as Yawgmoth’s Will. In fact, some decks can safely ignore Balance, such as Ichorid decks, where Balance is at most a minor annoyance, and at worst, will backfire and help the Ichorid pilot.

Another reason that Balance is less damaging today is because Vintage is so much faster than it was in the past. You had time to empty your hand, play some burn spells, and activate Bazaar of Baghdad a few times before casting Balance. Vintage decks don’t have that kind of time to spare. To be effective, Balance needs to do something asymmetrical on turn one, two, or three. Creating that kind of asymmetry in a productive and viable strategy that quickly is not as easy as it sounds.

So, at a minimum, there are two conditions that must be satisfied to build a deck around Balance:

1) Balance would have to be largely asymmetrical

2) You would need a way to resolve Balance reliably

The second condition entails the ability to generate white mana and mechanisms for protecting Balance.

The first condition entails at least two sub-conditions.

a) You will likely not be playing a non-creature deck or a creature-light deck in order to meet the asymmetry condition.

b) You will need a way to play lots of non-affected permanents more quickly than your opponent AND/OR to discard your hand quickly for some beneficial side effect.

I think the potential for Balance is to be found within sub-condition (b).

I would note that sub-condition (b) is probably in some tension with the overall second condition, since decks that empty their hand quickly or play lots of permanents tend not to have as many ways to protect Balance from being countered.

The two cards in Vintage that allow you to play permanents and spells quickly are Mishra’s Workshop and Dark Ritual. Mishra’s Workshop in particular fits the bill since the permanents played off of it by definition are unaffected by Balance, satisfying the asymmetry condition fully. While Dark Ritual does not have such a constraint, Dark Ritual has additional potential in allowing you to play Black enchantments or other discard spells that can protect Balance.

Two other accelerants that rank immediately behind Mishra’s Workshop and Dark Ritual as cards that allow you to play lots of permanents, but simultaneously, through their own function, also lower your hand size, are Chrome Mox and Mox Diamond. My initial conclusion is that any serious Balance deck will use one or more of these four accelerants.

Finally, there remain a host of cards that allow you to efficiently lower your hand size, beginning with Bazaar of Baghdad, but also including Call of the Court, and others. On this point, Retrace, dredge, madness, and flashback are all potentially good with balance.

Taking each of these design options in turn:

Mishra’s Workshop decks provide the most obvious home for Balance, not simply because of how well Mishra’s Workshop helps you accomplish the asymmetry condition, but also because 5c Stax has been the sole home for Balance for the last five years.

Here is my attempt at 5c Stax with 4 Balance:

4 Balance

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Tinker

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Crop Rotation

4 Sphere of Resistance

3 Chalice of the Void

3 Crucible of Worlds

4 Tangle Wire

1 Trinisphere

4 Smokestack

1 Karn, Silver Golem

1 Triskelion

1 Chronatog Totem

2 Goblin Welder

1 Black Lotus

1 Mana Crypt

1 Mox Sapphire

1 Mox Jet

1 Mox Ruby

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Pearl

1 Mana Vault

1 Sol ring

1 Bazaar of Baghdad

1 Strip Mine

1 Tolarian Academy

4 Gemstone Mine

4 City of Brass

4 Mishra’s Workshop

4 Wasteland

Notes:

• I have not included Mox Diamond for two important reasons. With or without Balance, Mox Diamond is amazing in any opening hand for 5c Stax. The problem with Mox Diamond that’s not the problem. The problem is that Mox Diamond is awful when you mulligan. Secondly, it makes your Chalices even more painful. If you want to run Mox Diamond, and I would say run two at most, you cannot run Chalices.

• Even with 4 Balance, I would still include at least a couple of Goblin Welders, and Trike for sure, even if you decide to leave Karn at home.

• I included Chalice of the Void here since it can help you lower your hand size and create a more robust Balance effect.

• I would also consider trying to fit an Imperial Seal and even a Yawgmoth’s Will in here somewhere.

• I prefer a pair of Seal of Cleansing over Tangle Wires, but that’s just me.

To be completely honest, it’s hard to imagine a better home for 4 Balances than 5c Stax. Balance fits the theme, meshes well with the other effects in the deck (such as Sphere and Crucible), and provides maximum asymmetry.

However, I would like to explore other options with Balance.

What might a Dark Ritual Balance deck look like? I started thinking about Phyrexian Arena, but then came up with this with the ideas of my teammates:

4 Chrome Mox

5 Moxen

1 Mana Crypt

1 Black Lotus

1 Sol Ring

1 Lotus Petal

4 Dark Ritual

4 Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author]

4 Polluted Delta

2 Bloodstained Mire

2 Swamp

4 Duress

4 Thoughtseize

4 Balance

4 Leyline of the Void

4 Helm of Obedience

3 Sensei’s Divining Top

1 Demonic Consultation

1 Necropotence

1 Yawgmoth’s Bargain

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Imperial Seal

1 Enlightened Tutor

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Darkblast

Notes:

• This shell can abuse both Dark Ritual and Chrome Mox.

• It uses Thoughtseize and Duress to protect Balances and help keep you in the game while you assemble your combo.

• The Helm + Leylines Combo is probably one of the most clever you can use with Balance, since both combo parts satisfy the asymmetry condition.

• Leyline also lowers your handsize since it can be played on turn zero. You could imagine turn zero Leyline, turn one Chrome Mox (imprinting something), Dark Ritual, Duress, Land, Balance as a potential opening hand. From there, you would empty your opponent hand, removing it from game in the process. You’d simply have to win topdeck wars from there on out.

But what about trying to more robustly synergize with Mox Diamond, Retrace, Dredge, and other similar effects? We’ve looked at the use of Workshop, Ritual, and Chrome Mox. That leaves one last obvious avenue left:

Loam Balance List:

4 Balance

4 Duress

4 Thoughtseize

4 Raven’s Crime

4 Life From the Loam

1 Worm Harvest

1 Darkblast

1 Ancient Grudge

1 Recoup

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Crop Rotation

1 Imperial Seal

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Regrowth

4 Mox Diamond

3 Bazaar of Baghdad

3 Wasteland

1 Strip Mine

6 Fetchlands

2 Bayou

2 Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author]

1 Badlands

5 Moxen

1 Black Lotus

1 Mana Crypt

1 Sol Ring

1 Lotus Petal

Notes:

• Just like the Dark Ritual/Chrome Mox version, this deck would use 8 Duress effects to protect Balance

• From there, it would generate card advantage through Life From the Loam and Raven’s Crime recursion, which also synergizes with Mox Diamond.

• I’m sure this decklist could be improved upon, but it’s merely a first draft.

And for one more idea on how to use Mox Diamond and Balance, consider this:

Meandeck Parfait w/ 4 Balance

10 Plains

1 Strip Mine

4 Wasteland

4 Mox Diamond

1 Mox Pearl

1 Mox Emerald

1 Mox Sapphire

1 Mox Jet

1 Black Lotus

1 Sol Ring

4 Aven Mindcensor

4 Land Tax

4 Scroll Rack

4 Aura of Silence

4 Balance

3 Argivian Find

1 Seal of Cleansing

1 Zuran Orb

1 Trinisphere

2 Orim’s Chant

2 Abeyance

1 Enlightened Tutor

2 Goblin Charbelcher

3 Swords to Plowshares

A year ago, I thought Balance would have been an excellent candidate for unrestriction. The Gush-metagame featured incredible topdecking capacity on account of cards like Merchant Scroll, Brainstorm, Ponder, and to a lesser extent Dark Confidant. Being Balanced certainly would not have meant what it used to mean. You could be balanced down to 2 cards and no land and pop a Mox, Land onto the table, topdeck a Scroll the following turn and easily overtake your opponent.

Today, it is not nearly as easy to topdeck your way out of being Balanced, but the decks that might best abuse Balance are much less fearsome. During the first 6 months of 2008, with a brief exception, Mishra’s Workshop decks were either tied for or the most successful engine in Vintage. Today, Stax decks are a measly 5% of the Vintage field, and Workshop Aggro roughly 10%, with Workshop decks, in the aggregate, making up about 15% of the field. Balance could help restore Workshops to their Gush-era levels in the metagame, which would be a tremendous boon for the diversity of the format. Part of the reason for this is that Mishra’s Workshop decks lack a solid answer to Inkwell Leviathan. With Balance in the format, you would really have an opportunity to address the problem of Tinker for Leviathan.

I believe that 4 Balance Workshop decks could return to their former glory of 20-25% of Top 8s, providing perhaps the best foil to Mana Drain decks. I think that this unrestriction would be particularly powerful with the unrestriction of Gush. If both Gush and Balance were simultaneously unrestricted, I believe that the synergies would be enormous for the diversity of the field.

The one issue is whether Balance would be too “unfun.”

As Peter O(aka DicemanX) put it on the Mana Drain:

Balance is fundamentally a parity card; to break parity a player would have to design a deck around that goal, which leads to significant concessions (refraining from building actual card advantage through U/B spells/effects). For those that drew parallels between Balance and Trinisphere in Stax, I would contend that a first turn play of Land, Mox, Balance is hardly fearsome, and the much rarer land, Mox, Mox, Balance, is also not as devastating as might first appear, since the Balance deck just gained +2 card advantage but has fewer ways of continuing to gain more card advantage – the Drain based archetype has many ways of quickly recovering and the interesting struggle will continue.

Balance-based strategies are the very antithesis of all current Mana Drain strategies, and would provide a highly potent challenger to the deck that appears to be dominating the current metagame.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Unlike Trinisphere which does not permit you to play a spell for the rest of the game, Balance would not be that swingy. Early Balance would still leave you with plays most of the time. Similar fears were raised over Mind Twist, and they have proved unfounded. It’s simply not feasible to easily and consistently achieve the blow-out play on turn one or early enough to create a Trinisphere-esque game state.

Final Verdict: Unrestrict

Conclusion

While there are other cards that merit consideration for unrestriction, these are four cards that appeared to be among the best candidates for helping restore greater metagame diversity to the Vintage format. I have tried my best to provide a balanced and objective analysis, and predictions as to how these unrestrictions would likely play out. Two candidates, Gush and Balance, stand out as potentially brilliant unrestrictions for the reasons described in this article. I hope that the DCI considers unrestricting some of these options as it conducts its quarterly review of the Restricted list in the coming weeks.

Until next time…

Post-Script

Last week, the same recurring objections and criticisms were raised in response to my analysis. These points are made over and over again in different places and by different people. I feel I did not do a very good job of addressing them in a concise and clear manner. Let me address them, more directly, one at a time.

1) Mana Drain decks are beatable

A common objection is that Mana Drain decks don’t need to be answered because they are very beatable. People point to decks that they have designed, or which, in theory should beat Drain decks. This claim has a very simple answer.

Every Deck/Engine in Magic is Beatable, that Doesn’t Mean it isn’t a Problem. Dominant decks/engines are always beatable. In fact, I’m not sure it is possible in Magic to create a deck that can’t be beat. In my experiment with unrestricted Vintage (http://www.starcitygames.com/magic/vintage/16641_So_Many_Insane_Plays_Unrestricted_Vintage_A_Magical_Experiment.html), I discovered that even at that level of insanity you could design a deck to beat any other deck. Just because a deck/engine can be beaten doesn’t mean it isn’t too good from the perspective of the health of the format.

2) Using Top 8 Data to Prove Dominance is Flawed because it does not suggest whether the proportion of Mana Drains in top 8s is disproportionate to their representation in the field.

This is the most common, and most complicated, claim to address. I attempted to address it in my article last week, but do not think I was particularly effective at explaining myself.

We have good reason to think that Mana Drains are not underperforming relative to the field. If Drain decks were underperforming relative to the field, then we would expect that the decks that were performing better would, over time and in the aggregate case of hundreds of players (which is what the data I use represents), make their way to the top.

This is why I look at trend data rather than a snapshot or a short period of time. The metagame must have time to react and adjust. But when we see dominance of a particular engine over time, then we know that the problem is real, and not ephemeral or merely a function of the relative proportions of the field.

But! It is objected, people don’t switch decks! This the second commonly heard claim:

3) Drain Decks are Winning Because People Prefer Drain Decks, and Good Players Prefer Drain Decks — I.e. Vintage Players Are Stubborn/ The Player Preference Argument

I concede that some proportion of the field will be “stubborn” and play the same deck regardless of their performance, until after a long enough period they either change or quit trying to compete. However, we know that enough players do switch to make a difference in terms of Top 8s proportions, as the Gush and Trinisphere and other eras prove. If it was simply player preference projected into Top 8s, then those eras would have had different results.

It only takes a tiny number of people to make the switch in any field to make a difference. For example, only one player per archetype in a tournament has to make top 8 on average with a different archetype for that archetype to make up over 10% of top 8s in total. Tournament top 8s are very sensitive to small changes in player deck choices, provided that those deck choices are high performers. The data reflects this.

Even if 90% of players play the underperforming archetype, it only takes the remaining 10% to switch to totally transform what top 8s look like in the aggregate. This suggests, contrary to the underlying assumption, that other decks are probably not better choices for the tournament.

Thus, the point is made: if Necro decks were 60% of the field, but 40% of tops, then they wouldn’t be a problem because they are underperforming However, the question would be: why would the large proportion of Necro decks persist, even though it has been shown that in terms of raw proportions, they are only the third best performing deck? The answer is very simple: they may still be the best deck choice.

Most obviously, the Necro players may still believe that the Necro decks give them the best chance to win the tournament, even if they make top 8 in slightly lower proportions than a few other deck options. One could imagine how this might be the case. The fact that people haven’t switched away should not suggest that people are stubborn, but rather the belief that people have that those decks give them the best chance to do well in the tournament.

Consider Mana Drains. Even if Mana Drain decks put up lower proportions of Top 8s relative to the field as compared to, say, Ichorid decks. Mana Drain decks give you the absolute best chance of winning a tournament once you are in a top 8. Mana Drain decks, for example, were only 42.5% of Top 8s, but they were 66% of tournament wins in March and April. As another example, Mana Drain decks were 30% of the Day 1 Waterbury Field, but they were 43.75% of the top 16, and the eventual tournament victor. Mana Drain decks may be the optimal game theory option, even if they underperform relative to their proportions in the field, for this reason and more.

Importantly, the argument that players are stubborn and prefer Drain decks suffers from what is known in psychology as the ‘fundamental attribution error.” This is an error in the way that human beings tend to think and process information. Without getting too technical, what it means is that human beings tend to over-attribute individual personality characteristics for a particular outcome and underemphasize the importance of situational factors. This form of bias is simply a function of how our brains operate, but it is pervasive in this debate.

4) People Should Switch to Non-Drain Decks That Beat Drain Decks

This is essentially the flip side of claim (3), and another example of the fundamental attribution error. It assumes that people aren’t switching to non-Drain decks.

The fact that Drain decks have performing at consistent levels over time does not imply that people have not attempted to beat them. In fact, we have seen many counter-strategies develop, with varying degrees of success, only to be countered by Drains themselves or to be gobbled up by the rest of the metagame. It’s not enough for an archetype to beat Drains if it is weak to the rest of the field. Also, it doesn’t matter if those decks can beat Drains in a top 8 if they are simply not good enough to win tournaments. Fish decks don’t win tournaments. Drain decks win a super-majority of tournaments.

There are more than enough Fish and Dark Ritual decks played in the tournaments to be the most dominant archetype by Top 8 data if these decks actually outperformed Drain decks. They clearly do not. This means that other decks are not better performers than Drain decks, even though people can cite anecdotal evidence of decks beating Drain decks. In almost every instance, the Drain deck nonetheless went on to outperform the supposed Drain foil.

5) Nothing Should be Done Because People Will Still Play Blue heavy decks Even if you Restrict Thirst or Drain

Although defeatist in some ways, this argument overstates its case. The concern is not that people will continue to play blue and black decks in heavy numbers, it’s that they are dominating top 8s at levels that are unacceptable.

Even still, it’s a matter of degree. The objection that I have with the current metagame is not that Mana Drains are the best engine, rather it is their degree of dominance, and the total absence of a viable alternative that puts up even remotely comparable numbers. IN the Gush era, Workshops and Gush were roughly comparable. If Mana Drains were around 35%, that would be a substantial improvement over their consistent 40%+ range, especially if Rituals and Workshops were boosted even a modest amount.

While I agree that people will still play blue decks, that does not mean that nothing should be done. We have a full year of experience from June 20, 2007 through June 20, 2008, where the metagame was much more diverse from an engine perspective. That metagame is preferred to this one in terms of the diversity of the format, even if you tweaked it slightly. While I agree that it is futile to try and get people to not play blue (blue would be the best color if every blue card were restricted), that does not mean that this metagame should not be adjusted by DCI action to create a better one.

In sum: the goal is not to re-balance the format against blue, per se, since blue will always be dominant, but to create greater strategic and archetype diversity within that constraint. Diversity is a critical component to a healthy metagame. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be a best deck, but it is a matter of degree. Thus, the Gush metagame had lots of blue decks, but Flash, Gush, and Drain Tendrils were each very different archetypes with different engines, vulnerabilities, and advantages. The current levels of dominance are far beyond what is acceptable or what has historically existed, and it can and should be different.

6) People just switched from Gush decks to Drain decks, that if you look at the data, we simply have mashed the chunk of Drain decks over the chunk of Gush decks to get our current Mana Drain levels. Relatedly, Gush and Drain decks are just the same.

Gush and Drain decks, while utilizing Force of Will, were very different animals. Gush decks and Drain decks both ran 4 Force of Will and 4 Brainstorm, but the Drain decks then ran 4 Drains and 4 Thirsts (for the most part), whereas the Gush decks ran 4 Scroll, 4 Ponder, and a very different set of cards. The Gush decks were Oath, Grow, and Painter, and the Drain decks were Control Slaver, Drain Tendrils, Painter (a variant without Gushes), and Bomberman. If Gush and Drain decks were the same deck, then why not call Ritual decks also the same deck, since they shared 4 Force and 4 Brainstorm? The fact of the matter is that they were not the same deck anymore than TPS and Control Slaver, for sharing 4 Force and 4 Drain, were the same deck. They were different strategically and tactically, substantially so. That’s why I suggested, last year, unrestricting Fact or Fiction, to help boost Drain decks presence in the field a bit.

7) Time Vault is really to blame

I made a mistake by trying to address this point in my previous article. The short answer is: even if this is true, it is completely irrelevant. We do not ban cards in Vintage, so the DCI has to look for other answers.

Although the question of the role of Time Vault is irrelevant to the issue of what to do about it, I do want to address the question of to what extent Time Vault really is responsible for the current predicament. I will concede that the data does suggest that Time Vault is a contributory factor to the current degree of Mana Drain dominance. It is impossible to disaggregate the data in a regression analysis since there are multiple factors intertwining that produce the system/metagame outcomes. My analysis suggests that Time Vault has impacted the metagame in several ways:

1) I believe it is responsible for 5-8% of the current degree of Drain dominance. Without Vault, Drains would still be far and away the best performing engine by Top 8. In the three months before Time Vault was legal but after Gush was restricted, Drains were already trending upward at a dramatic rate around 35+ % of the field.

2) The major difference is that in the pre-Time Vault field, Mana Drain decks were broken up into many different archetypes, such as Painter, Slaver, Bomberman, Drain Tendrils, etc. Now, they are consolidated into a single archetype or one major archetype with several variants.

3) The most important difference might be that Drains percentage of tournament victories would be lower. In the two months data set before Time Vault really took off, Dark Rituals actually were the most tournament winning archetype.

Time Vault has contributed to the current performance of Drains. Time Vault has helped create an archetype that is basically a hair away from Meandeck Gifts in terms of its metagame presence and tournament dominance/power. That said, Drains would still arguably be above the acceptable level of format dominance even if Time Vault were not around.

Even if banning were on the table, why would Time Vault be the most sensible target? How would banning Time Vault make more sense than banning, say, Tinker? Tinker and Yawgmoth’s Will are both more powerful than Time Vault.