There are an infinite number of possible Magic cards.

Of course, most of those cards would end up being gibberish—monkeys on typewriters and all that. I don’t expect we’ll ever see an enchantment that reads, “Tap, Eat the minnow: Draw nine cards, then Wombat X,” even if that card would probably be pretty rad.

Complexity has increased by a good deal since the game was invented, though. A thousand new cards are designed and developed each year, and not all of them can be as simple as Hill Giant. Imagine trying to explain Bonfire of the Damned to someone who hadn’t played since Alpha. What’s the special border for? How come it says ‘sorcery’ when there are times you can play it on your opponent’s turn? Why is it so freaking good?

Magic’s complexity creep hit an apex during Time Spiral block, when an intimate knowledge of Magic’s rules and history were practically required to figure out what each card did. I urge all of you to watch Aaron Forsythe presentation on this year’s Magic Cruise where he talks about the successes and failures of each set between the last Ravnica block and this one. The audio quality of the recording is terrible, but the content is worth it.

In the video, he goes into great detail about just how problematic this complexity creep was to the continued success of Magic. Even though the game is more complex than it used to be, things have gotten considerably easier to understand in recent years. Starting with M10 and Zendikar, Magic sales have been surging, and simpler design lowering the barrier of entry is a big part of why.

The problem with keeping things simple, however, is that it shrinks the amount of possible design space. How many mechanics do you think have been designed and discarded over the past two years because they were simply too complex to work at common? Magic design is in a great place right now, but in order to keep making new and exciting cards some boundary has to be pushed.

Increasingly, that boundary has been power level.

This is a simplified look at things, but take a quick gander at the evolution of aggressive white one-drops over the history of the game:

None of these cards are ‘strictly better’ than any of the others. Isamaru has a drawback in the fact that he’s legendary. Elite Vanguard is has the creature type ‘soldier,’ which comes into play in many games. Dryad Militant has a static ability that is likely to be beneficial but is nonetheless symmetrical.

Is it a problem that Dryad Militant is better than Savannah Lions 99% of the time? Not really. As Forsythe said on Twitter when the card was revealed, it’s not as if Savannah Lions is tearing up Legacy at the moment. This is an example of relatively safe and benign power creep.

Dryad Militant is, however, indicative of Magic’s current trend toward pushing the boundaries of what certain creatures and spells are capable of accomplishing. And this is something collectors and speculators should always be cognizant of.

In many ways, Magic finance writers are the futurists of the game. We sift through large amounts of data, both mathematical and anecdotal, in the hopes of predicting what cards will be in demand next week, next month, and next year. When making a call on a freshly revealed Return to Ravnica card, I not only have to think about how it fits into the presumed Standard metagame but also how it compares historically to hundreds of other cards.

Power creep is one of the biggest reasons that cards lose value over the long term. Heck, Savannah Lions was a $5 card for about a decade. In fact, there were many years where you could trade away two or three Savannah Lions (currently $1 each) and get a Savannah (currently $100) in return.

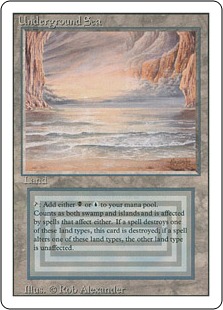

The reason for that is because Wizards of the Coast R&D decided that Savannah Lions, once the most efficient one-drop creature in the game, was not as powerful as a 1CC white creature could be. They also decided that the dual lands were at the absolute limit of how powerful a mana fixing land should be. Because of that, Savannah is still the absolute best land in the game at fixing Selesnya’s mana while Savannah Lions has long been outclassed.

If Magic had evolved differently and we had a common land that tapped for green, white, and blue with no drawbacks while the power level of creatures had remained stuck in the Ice Age days, chances are Savannah would be the $1 card and Savannah Lions would be pushing $100. (Or, more accurately, neither card would be worth much because the game would have gone out of print years ago.)

So which kinds of cards are safe to invest in? Which staples are next to get steamrolled by more powerful or efficient competitors? What does the overall increase of Magic’ power level mean for the future of the game? Let’s find out.

Alpha Again

I know—I spend a lot of time harping on Alpha in this column. I’m a real sucker for the early stuff. Just last weekend, I traded a moderately played Force of Will for a heavily played Alpha Sol Ring. Even though the card is worn, I love the feel of it—the corners rounded even more from twenty years of being shuffled and cast over and over again.

The reason why Alpha is important in this context is that it provided a power baseline for the game of Magic that was used right up until the release of M10. If you think of Magic like a house, Alpha was the original foundation. The house has been leveled and rebuilt several times over the years, but the foundation had never been rebuilt until the start of Mark Rosewater New World Order. Up until that point, everything was still in some way a reflection of Alpha’s design and development.

While nearly every card in Alpha has inspired dozens of others, there are a few that I want to specifically highlight:

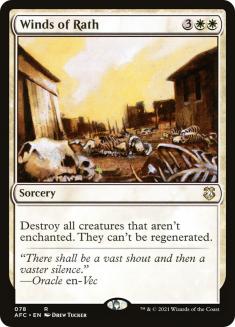

This subset of cards acts as the baseline for which many of the most prevalent effects in Magic follow to this day. For instance, let’s take a quick look at some of the cards printed over the years that function similarly to Wrath of God:

Since the very beginning, we’ve all accepted that 2WW is the appropriate casting cost for a spell that wipes the board. There has never been a spell that lets you destroy all creatures at 3CC—those cards (such as Slagstorm) are always more situational. Further, most 5CC and 6CC Wraths have some sort of upside attached to them, such as the ability to cast them at instant speed. It’s kind of amazing that Magic’s first board sweeper has resonated throughout the game for twenty full years.

It’s also interesting to look back and see which cards in Alpha didn’t really catch on. Stone Rain was the basis for almost all the land destruction cards for years, but Sinkhole was also a common in Alpha. Land destruction could have just as easily been made black over the next few years instead of red. Instead, Sinkhole became a historical curiosity and Stone Rain was reprinted a half-dozen times.

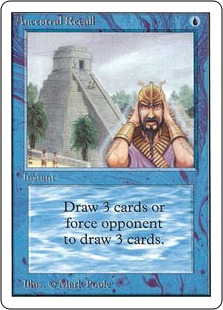

Looking back at Alpha, it’s clear that Richard Garfield hadn’t quite figured out how to correctly balance the cost of each effect. Drawing three cards, for instance, only cost one mana in the form of Ancestral Recall. Nowadays, a similar card would cost four to five mana. While people realized that Ancestral Recall was broken pretty early on, these Alpha baselines were still hard to shake. This is why most of the best card draw spells in the game are from many years ago.

On the other side of things, Shivan Dragon used to be Magic’s premiere game-ending creature. Kids everywhere warped their schoolyard decks around playing this guy, and he rarely landed on the table without generating a defeated gasp from an opposing player. Nowadays, we have this guy:

Granted, the power level on this card has been pushed a bit to make it one of the marquee mythic rares of M13, but even still it’s not seeing all that much tournament-level play. While the spells of Magic have been either getting less powerful or staying the same, the game’s creatures have been getting better.

Pulling Back

When looking for cards that will always have value, it’s a good idea to take stock of the strategies and abilities that Wizards doesn’t aggressively push anymore. For example, Ancestral Recall is likely to stand forever as the best card draw spell in the game. Strip Mine will always be the best land at destroying other lands. Eternal formats are always going to try and be about ‘unfair’ Magic, and casual players are always going to enjoy doing undercosted things. When in doubt, investing in these sorts of cards makes sense from a long-term perspective. None of these cards will ever be outclassed, and they should all hold their value fairly well.

Here are a few things that Wizards has pulled back on significantly:

- Early game card draw

- Counting spells

- Reanimating creatures

- Tutoring for cards

- Destroying lands

- Fixing mana without a drawback

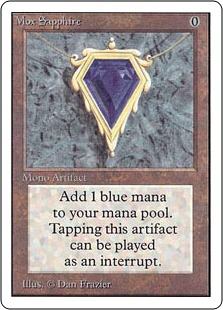

- Cheap lands/artifacts that produce lots of mana very quickly

- Producing a lot of ‘fast mana’ (e.g., Dark Ritual)

A lot of these things were curbed fairly early on, but since the New World Order rebuilt Magic’s foundation the ‘old’ cost for doing them has gone up permanently. Animate Dead and Demonic Tutor haven’t been Standard legal for a long time now, but we’re past the days of Exhume and Diabolic Intent as well. Even though Magic’s overall power level has gone up and will likely continue to do so, I don’t think we’re going to see an increase in aggressively costed cards that allow the above strategies to be as powerful as they have been in the past.

Why has Wizards dialed down these effects in particular? For the most part, they reduce interactivity. Countering too many of your opponent’s spells or destroying all their lands in the early game is going to lead to a frustrated player. Ditto for decks that have too much speed or redundancy in their ability to get a combo off. Too much fast mana and too many good Tutors or Reanimation spells lead to unwinnable scenarios on the first few turns of the game. Instead, Wizards R&D has pushed Magic toward a place where both decks are allowed to try and win on their own terms.

Forging Ahead

While countermagic and card draw have been weakened, other aspects of the game have been considerably strengthened in the New World Order.

Here are a few things that R&D has been costing more and more aggressively:

- Creatures (at all points on the curve)

- Spot removal

- Creature enchantments

- Pump spells

- Life gain

- Late game spells

Take a look at the best-selling preorders from Return to Ravnica—except for the planeswalkers and the requisite ‘gold set’ mana fixing, they’re all on this list.

While creatures have been ratcheting up in power for a while now, it’s arguable that this isn’t power creep so much as the search for a balance of power that didn’t exist for most of the life of the game. The fact that spells act immediately while creatures generally need a turn before becoming useful is a bigger deal than it initially appears, and it took Wizards a long time to realize that. By powering up creatures and spells that interact directly with creatures, Magic has been not so subtly redesigned to focus on the combat phase.

Let’s take a quick look at Urza’s Saga, one of the most financially lucrative sets of all time. Here are the cards worth more than $20:

- Exploration

- Gaea’s Cradle

- Gilded Drake

- Serra’s Sanctum

- Show and Tell

- Sneak Attack

- Time Spiral

- Tolarian Academy

By my count, that’s one broken card draw spell, four cards designed to massively ramp up mana, and three cards that became bonkers with today’s amazing creatures. Gilded Drake is the only creature on the list, and that card has only gone up in value thanks to how amazing today’s giant beaters are.

You know what card isn’t on this list? Morphling. It’s true that the removal of damage on the stack during combat was the deathblow for this guy, but his time had come and gone long before that. For years, Morphling was regarded as the best creature in the entire game. Now, he’s easily outclassed by finishers like Wurmcoil Engine and Consecrated Sphinx.

The same is true for other venerable creatures from Magic’s past like Spirtmonger, Wild Mongrel, and even Psychatog. Aside from a few cards that were probably development mistakes of one kind or another, today’s creatures run laps around the monsters from yesteryear.

When Power Corrupts

Magic has made an obvious effort to ‘power down’ twice over the past fifteen years: once in the drop from Urza’s Destiny to Mercadian Masques, and again in the jump from Fifth Dawn to Champions of Kamigawa. Both times, the overpowered block drove customers away thanks to a degenerate Constructed metagame and the underpowered block did nothing to bring them back. Screwing up the power balance took a full two blocks to work itself out and for the ship to right itself once more. Needless to say, this likely isn’t a mistake that Wizards is eager to repeat.

Of course, power creep in Magic is most often measured by the best cards in a given set and not the body of cards as a whole. While Urza’s block is considered to be among the most powerful of all time, most of that is thanks to a small handful of cards. The other 600 or so spells were rather harmless. Mirrodin block likely wouldn’t have been remembered as being totally nuts had Arcbound Ravager, the artifact lands, and Skullclamp not been printed. (For whatever reason, Worldwake got a pass on this even though it had Jace, the Mind Sculptor and Stoneforge Mystic.)

There is some worry among many players I’ve talked to that Return to Ravnica is too powerful. At SCG Open Series: Los Angeles and the last two FNMs I attended, multiple conversations about the ludicrous power level of the set occurred. People are excited, but they’re also worried about the long-term health of the game. Can Magic survive if cards have to keep getting better and better? Will the next block have to be a Masques-esque hangover to make up for Ravnica’s raw power?

I highly doubt it.

Cyclical Creep and Return to Ravnica

In the online game World of Warcraft, there are different classes of character that each have their own set of strengths and weaknesses. Priests are good at healing, Warriors are good at absorbing damage, Mages are good at casting spells, etc. Over the years, players constantly called out for Blizzard to buff certain classes while nerfing others—tweaking damage modifiers and introducing new items so that everyone was at a roughly equal power level.

But things were never equal. There was always one class that was the most powerful and one that was the least powerful. Every time the game was patched, the balance would shift slightly. Over the years, every single class had seasons where they were unbeatable and seasons where they were easy to defeat. By shifting the balance of power instead of continually increasing it, Blizzard was able to curb the need for power creep for years. (Then, of course, the expansions were released and characters became so powered up it was ludicrous. For a while, though, their system worked quite well.)

Right now, I think this sort of ‘cyclical creep’ is what Wizards is trying to do with Magic. By temporarily weakening certain strategies while pushing the boundaries of others, it becomes possible to always create the illusion of more and more powerful cards. This is hard to pull off, but R&D has been quite successful. Each of the different colors and major New World Order strategies—control, aggro, and tempo—have had a chance to wax and wane in recent months.

The advantage of embracing cyclical creep is that the game won’t always be ramping up in power. If a card like Lightning Bolt is always being reprinted, Wizards is continually pressured to print something better in order to drive excitement and sales. If Incinerate / Searing Spear is the baseline instead, Lightning Bolt can come around ever few years as a safe and exciting upgrade. WotC already knows it won’t break the game open, and players get to feel like the power level of their decks is going up. It’s a win-win. Rinse and repeat for Rancor, Mana Leak, etc.

Right now, most of the expensive cards in Return to Ravnica are riffs on earlier powerhouses. Abrupt Decay is some combination of Terminate, Vindicate, and Maelstrom Pulse. While it’s arguably the best of the three, that claim certainly isn’t clear-cut and the utility is quite situational. Chromatic Lantern has both strengths and weaknesses compared to Coalition Relic. Angel of Serenity is better at some things and worse at others than the rotating Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite. Rakdos’s Return is better than Blightning if you have a lot of mana but is much worse if you don’t. Jace, Architect of Thought is more powerful than Jace, Memory Adept and less powerful than Jace, the Mind Sculptor. The shocklands are literal reprints. Only Vraska the Unseen feels totally unique to me, and a gold 4CC planeswalker is unlikely to push Magic further toward the abyss.

What is unique about Return to Ravnica, I believe, isn’t the overall power level of the set—it’s the unprecedented depth of quality at the rare slot.

When looking at tournament playable cards, specifically the best 5-10% of a given set, Return to Ravnica is nothing special—we’ve had cards like Abrupt Decay and the shocklands before. When looking at the number of excellent casual rares, however, it is clear that Wizards is continuing a push they’ve made in recent years to increase the number of happy faces when opening a pack of cards.

The popularity of casual formats like Commander and Cube along with the focus on sets like Planechase and Archenemy have helped Wizards R&D better tap in to the sorts of things that casual players like doing. If you combine this with the massive boost that creatures have gotten over the past few years as well as the fact that gold spells can be aggressively costed, you get the recipe for the possibility of more casual-friendly rares than ever.

Let’s compare the Selesnya rares in Return to Ravnica with the rares in original Ravnica and see how they stack up. Ravnica, remember, was a wildly popular set in its own right.

These are the seven G/W rares from Ravnica: City of Guilds. Loxodon Hierarch and Glare of Subdual both made a splash in constructed, and both are still fringe-playable in cube. Tolsimir Wolfblood is a reasonably popular Commander general, and Priviledged Position is a pricey Commander staple. Autochthon Wurm, Chorus of the Conclave, and Phytohydra are only about a notch above bulk.

Which is a better collection of cards? From a tournament perspective it’s too early to tell, but I expect Loxodon Smiter will see play for sure and Armada Wurm and Trostani will show up from time to time. Selesnya decks were just a small corner of the Standard metagame last time out, and they might be a slightly bigger deal this time around. I don’t expect any of these cards will see much play in the Eternal formats.

From a casual perspective, however, it’s no contest. Token strategies have been popular for years, and all of these Return to Ravnica populate cards are a boon to the strategy. Selesnya’s rares in Ravnica: City of Guilds are all over the place—do you want to cast a giant Wurm? Play tempo with Glare of Subdual? Control the board with Phytohydra? In Return to Ravnica, on the other hand, Selesnya’s rares work together and form the backbone of a casual deck that people are going to be immediately drawn to. Each rares makes all of the others better. Because of this, there are much fewer ‘blanks’ in the rare sheet than ever before. This may feel like power creep, but it’s not—it’s just quality set design.

Bringing It All Back Home

In the end, I don’t think Magic has a serious power creep issue. Certain aspects of the game were imbalanced from the start, and the power level for those cards has gone up considerably over time to compensate. That changed with the New World Order, and I think that the power level of cards since M10 has been fairly consistent. Certain colors and strategies will get “safe” power-ups from time to time, creating the illusion that Magic is getting more and more powerful. I wouldn’t be afraid to invest in cards anymore with the belief that creatures will continue to keep getting better, outclassing today’s current crop of awesome dudes. I would, however, feel even safer investing in older cards that were printed with the old baseline and will likely never be matched in power level again.

Don’t believe me that power creep isn’t a major issue? Check out the top decks from last week’s SCG Legacy Open. If power creep was a problem, these decks would contain a majority of new cards. Instead, these decks contain spells from the full history of Magic.

While the future of Magic design is unknown, I would only start to worry about power creep if things have taken a serious turn toward the absurd. Return to Ravnica isn’t the most powerful set ever, but it might be the deepest and the most fun. Enjoy it while you can—this is the golden age of Magic, and we’re lucky to be experiencing it.

Until next time—

—Chas Andres

|

I am Simic. When it comes to playing Magic, the blue/green color combination appeals to my desire to have both the best creatures and the most versatile spells. I always feel like I’m somehow handicapped when I don’t have access to Islands, but I still like ending games by throwing giant monsters at my opponents. From a philosophical standpoint, I feel as if the Simic represent humanity’s best possible future. Our species has been in conflict with nature for far too long, and that divide threatens to become our ultimate downfall. By combining the best of advanced science with a respect and understanding of nature, we humans can transcend our evolutionary limitations and become truly wondrous creatures. |