It’s better to draw too many lands than too few.

Class dismissed.

Seriously. That’s it. If you wanna save some fifteen minutes of your life, that’s what my whole article is gonna get around to.

Last week I invited readers to post their brews in the comments and was only slightly disappointed…and it wasn’t in the ideas that people had. It was that so many people were cheating on their land counts.

People regularly complain about flooding and remember drawing fifteen lands and dying because they bricked one or two times too many. The games where people get mana screwed don’t stick out as much because they’re over and done in a quarter of the time.

“What do you mean? Both options involve a player not getting to play as much Magic as they normally would.”

If the opponent is mana-flooded, it may not be so easy to sniff out at first. Against a deck with blue and red mana, it’s easy to think that they may just be holding counterspells or instant-speed interaction. This leads to one player staring at the cards in their hand, wishing they weren’t lands seven through eleven, and the other player trying to figure out how to play around Torrential Gearhulk or some other haymaker. The time that is sunk into this game, as opposed to the game where a player gets stuck on one or two mana before dying on the fifth turn, is incredibly different.

This, combined with a misunderstanding of card quality, leads to a number of reasonable players trying to cheat on their lands. It’s easy to fall in the trap of seeing a spell and thinking, “But this is a great spell! How could I possibly remove it from my deck for something as weak as a land?”

Mana Sinks in Standard

This kind of thinking ignores just how mana-hungry this Standard format is. Just look at the de-facto pre-banning “best deck” for #SCGATL:

Creatures (18)

- 2 Whirler Virtuoso

- 4 Servant of the Conduit

- 4 Rogue Refiner

- 4 Felidar Guardian

- 2 Glorybringer

- 1 Channeler Initiate

- 1 Manglehorn

Planeswalkers (8)

Lands (20)

Spells (14)

This deck only played twenty lands, but in a lot of ways was almost 50% mana.

All of these cards allowed the deck to cheat on its land count while still hitting a majority of its land drops. Traverse the Ulvenwald even has the added bonus of finding gas later in the game.

Even in a deck that only played twenty total sources of mana in the deck, there were many ways to ensure that the deck spent all of its mana every turn.

All of these cards were ways to use excess lands that the deck found later in the game, either by discarding Sheltered Thicket itself or providing a way to convert lands into fresh cards, and Nahiri allowed her controller to discard Forest #100 to try to dig for some action.

Not all of the mana sinks in this deck required other cards to do anything, either. Some of them were just X-spells that rewarded their controller for waiting to cast them until later in the game.

What did all of these have in common?

They all wanted their controller to have extra mana lying around.

The Price of a Mana Sink

Mana sinks aren’t efficient and they aren’t pretty, but they’re very good. A lot of it is in the price for versatility that comes with these cards.

Looking at Tireless Tracker as an example, drawing a card for two mana isn’t exactly a great deal. It’s the fact that Tireless Tracker does a lot in a single card. At the risk of sounding repetitive, Tireless Tracker gives its controller the ability to:

- Mitigate a mana flood by drawing multiple cards over the course of a few turns.

- Present an early must-answer threat against Control decks.

- Become an unmanageably large threat against other creature-based decks.

All of this makes the extra mana or two that each aspect of the card requires worth it.

The same can be said for Walking Ballista.

Walking Ballista was easily the most important permanent printed in Aether Revolt and it doesn’t look like that will be changing anytime soon. As if protecting its owner from the Shaheeli Rai / Felidar Guardian combo with only one counter weren’t enough, it keeps other creature decks in check, and can convert a bunch of mana into an insurmountable battlefield state if left untouched.

This isn’t the first time, and likely won’t be the last, that I reference the semi-finals match from #SCGCOL that Brennan DeCandio was able to win almost singlehandedly on the back of Walking Ballista:

There is a point in this game in which Brennan has enough mana to beat Hunter while hardly attacking. Just having excess mana from Rishkar, Peema Renegade allows Brennan to take his Walking Ballistas over the top of everything Hunter draws.

Even without an example as extreme as this, there are so many games that devolve to players having to answer eachother’s mana sinks as soon as possible. It’s because all these mana sinks are providing is free advantage from the opponent.

Free…. But at What Cost?

What is likely the most important development in the last five years or so of Magic is the understanding of Tempo versus Card Advantage.

The short version of it is that there is a balance between how much time (read: mana, turns) one can spend accruing cards while contributing to the battlefield.

For anyone who plays Hearthstone, this is hardly a new concept. In Hearthstone, instead of colors there are nine “classes” of cards that can be played, and each class gets a unique Hero Power. Each hero power costs two mana and can be activated once per turn. Though the effect varies from class to class, each Hero Power is a way to spend two mana and accrue a bit of value in addition to whatever cards a player has access to.

Mana sinks in Magic are similar. Activating a Walking Ballista is nice because it represents an extra point of power and toughness and well as an additional point of damage that can be thrown around at the Construct’s owner’s discretion, but four mana isn’t a small amount. Four mana is enough to cast one of the planeswalkers in the deck or some of the other more powerful mythics in Standard.

The reason that this is worth it is that, outside of the mana investment, it’s a way for a player to create a free resource out of nothing. Think of a card that doesn’t scale past whatever is printed on the card, something in the vein of Toolcraft Exemplar.

Without help, Toolcraft Exemplar has a ceiling that isn’t relative to the amount of time it is on the battlefield (outside of the number of times it gets to attack, of course). Toolcraft Exemplar is generally going to be worth three points of power, two points of toughness, and the single body printed on the card. That doesn’t sound a like a lot, but the tradeoff is that it hits the battlefield on the first turn and is really only good when it’s attacking.

Going back to Walking Ballista from the previous example, it’s hard to really determine how much the card is worth because it has no ceiling. The only things that really limit Walking Ballista are:

- The length of the game.

- An opponent getting Walking Ballista off the table with a removal spell or combat damage.

- Walking Ballista’s controller removing its last +1/+1 counter to deal damage.

Outside of that, every turn that Walking Ballista’s controller gets to untap, the more times they’ll untap and have the opportunity to grow Walking Ballista. Even ignoring the rest of the resources that a player may have available to them, each activation on the Ballista is just providing another resource that they can use that didn’t cost them any actual cards to generate.

Your Curve, Your Land Count, and You

In case it hasn’t quite gotten across yet, playing an abundance of lands is great. When Amonkhet even gave us a cycle of lands that cycle (ba-zing!), it’s pretty hard to reasonably justify cheating on one’s land count.

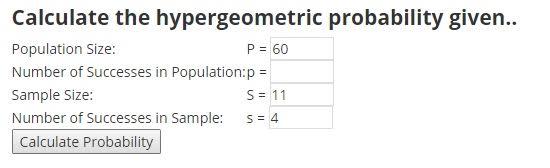

Even still, it’s nice to know just how many lands one can get away with playing (or not playing) in a deck while still maintaining the curve that their deck calls for. The easiest way to do that is to use a hypergeometric calculator.

Despite taking a little bit of learning to understand, a hypergeometric calculator that will effectively allow its user to know the probability to drawing a certain card or kind of card within a deck of X cards.

The calculator uses four fields, and to translate the technical mumbo-jumbo used in the hyperlink, each field should be filled out in this order:

- The first field should be how many cards remain in the deck.

- The second field should be how many of the desired card are in the deck. (In this case, how many lands are in the deck.)

- The third field will be how many chances you will get to find that card, via drawing cards.

- The fourth field is how many of the cards from the second field need to be drawn for the game to be considered a success.

After hitting the “calculate probability” button, the program will present the odds of drawing that many copies of X card after Y draws.

To use an example, imagine playing a deck that wanted to dependably cast Gideon, Ally of Zendikar on the fourth turn. This means that we already know three of the numbers to plug into the equation.

The deck size will be 60, we will generally have eleven draws (our opening seven plus four draw steps), and we need to hit four lands to cast Gideon, Ally of Zendikar. From here, we need to fiddle with numbers to see what the exact number of successes would be. By inserting each of the following numbers as land counts in the second blank, we get these numbers:

|

Number of Lands |

Chance of hitting first four land drops |

|

20 |

54% |

|

21 |

58% |

|

22 |

64% |

|

23 |

68% |

|

24 |

73% |

|

25 |

77% |

|

26 |

80% |

|

27 |

83% |

Looking at this table sheds a bit of light on why so many of the low-to-the-ground aggressive decks will either A) sideboard in lands when they want to play bigger spells or B) eschew more powerful four-drops altogether. Before hitting 24 lands, it feels like a bit of a pipe dream to reliably cast Gideon on the fourth turn.

Depending on the rest of the context of the deck, a strategy that relies heavily on having a four-drop enter the battlefield on turn 4 is going to want to play between 23 and 26 lands, 23 if the deck has a reasonable amount of ways to churn through its deck or is lower to the ground and 26 if the deck has a high number of mana sinks and plans to keep going bigger from the four-up. Another time that you may want to consider erring towards the higher end of things? When there are ways to convert ancillary lands into other cards.

I can’t really sing the praises of this calculator enough. Once you use it regularly, many of the numbers become ingrained in your head and it isn’t even necessary anymore, but for taking your manabase game up to the next level, this is a great way to do it.

Looking to Amonkhet

I wasn’t lying in the opening: all I want people to do is start playing more lands in their decks. The new cards in Amonkhet are incredibly exciting and likely will do a number for shaking things up in the format. With Felidar Guardian gone, Standard is brimming with possibility.

This weekend I’ll be competing at #SCGATL, likely with some cool tap-out synergy deck and a few too many mana sources. If you have something cool no longer being held back, make sure and drop it in the comments below! I love new ideas and adore the fact that there isn’t a looming presence of “trigger, target Saheeli” pushing Amonkhet‘s best out of Standard.