RIP, Magic e-books.

@Mechubus No ebook. We’re telling the full story through Uncharted Realms.

— Aaron Forsythe (@mtgaaron) September 25, 2014

Note that I did not say “RIP Magic storytelling,” because it’s far from dead. Magic has told stories through cards and other media since March 1994, when a

set called Antiquities introduced the world to a couple of brothers named Urza and Mishra.

Why Antiquities? The Gathering (as the first Magic set was envisioned before “The Gathering” became part of the game’s official title) had no cohesive

storyline, and Arabian Nights borrowed from the classic work of literature andthe “Ramadan” issue of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman but similarly had no plot thread.

The Wikipedia page on Magic storylines is a bit out-of-date (no

mention of the Return to Ravnica /Theros e-books or the IDW comics series), but it does give an idea of the breadth of non-card

Magic storytelling through the years. As the 20th anniversary of the first Magic novel approaches, it’s worth examining how various media have been used to

tell stories, abandoned, and returned to over time.

The Art (and Flavor Text) of the Cards

While non-Core sets (as they later came to be known) such as Fourth Edition, Fifth Edition, etc. didn’t have cohesive storylines, regular sets from

Antiquities through Apocalypse expressed tales through their cards. This is most obvious starting in the set Weatherlight, which kick-started the

adventures of Gerrard Capashen, Captain Sisay, and the rest of the Weatherlight crew as they set off on a quest they were (or at least Gerrard

was) born and bred to make.

The Weatherlight-through-Apocalypse period saw an “all there on the cards” approach to the storyline, where moments great and small were depicted in the

art of cards and expressed in their flavor text. A card like Vindicate, sci-fi trappings aside (Invasion block, and Apocalypse in particular, took on the

trappings of space opera complete with flying ships and giant mechs), expresses a climactic story moment that wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary

set; compare Deicide from Journey into Nyx. Then there are cards that make sense in context but come out of left field to newer players, such as Jilt.

Odyssey (the set and block) started another multiblock, multiyear storyline that ended up with a five-color Karona, False God doing a lot of weird

stuff, the character Jeska emerging back out of Karona, and said character then zooming around the Multiverse with Karn and visiting an all-metal plane

called Mirrodin with a guardian fashioned out of the Mirari, the superpowered MacGuffin of the two-year block. No, I didn’t start smoking Halflings’ Leaf mid-paragraph. That’s all canon.

It’s not exactly reflected in the cards though. Sure, the main players are set up, but there’s not a whole lot of plot transmission. This trend continued

through Mirrodin, to a lesser extent in Kamigawa (the card Michiko Konda, Truth Seeker tells part of a story that gets trippy in its own way), and then

reaches a nadir in Ravnica, a block that was set up to showcase ten guilds in a 4-3-3 manner, a structure that didn’t allow a plot to develop at all,

though there were occasional tie-ins and characters appeared in the novel trilogy roughly in the order they showed up in the sets.

First set, second set, third set.

Ravnica, Time Spiral (oh, what a trippy mess that was), and Lorwyn/Shadowmoor all kept the plot expression low, but recent sets have picked up the

storytelling pace. While Creative has figured out that telling a linear story doesn’t work well in a game that has shuffling as one of its primary

mechanics, a few incidents simply must be reflected in the cards, hence such cards as War Report (ending the Mirran-Phyrexian war, for certain values of

ending) and Deicide (ending the story of Xenagos getting toppled, again for certain values of ending). The newest set, Khans of Tarkir, has some good

storytelling moments, including Bitter Revelation and Despise.

The Magic Novel

Before Magic solidified its own “lore core” around the Weatherlight Saga, a number of already-notable and up-and-coming authors took their turns at writing

for the nascent Magic universe. The first Magic novel, Arena, was written by history professor andLost Regiment series author William R. Forstchen. Short fiction guru Bruce Holland Rogers wrote his second (and so far

last) novel, Ashes of the Sun, for the early Magic series under a pseudonym.

These early Magic novels were published under a HarperCollins imprint, Harper Prism, through the

end of 1996. The year 1997 saw no Magic novels published during a transition period, but Wizards of the Coast published its first in-house novel, Brothers’ War, in May 1998. This began the long sequence that went through the whole of the Weatherlight Saga and the three-books-a-year block

cycles from Odyssey through Time Spiral with a distorted echo in Lorwyn/Shadowmoor.

It’s worth noting here that I am not a lover of all early Magic novels, even though I’m a hardcore Vorthos. While Chainer’s Torment, the middle novel of the

Odyssey cycle, has engaging characters and works even without knowing the surrounding lore, the same can’t be said for its bookends Odyssey and Judgment. Sturgeon’s Law definitely comes into play with old works as well as new.

Things started getting weird around that time as Magic moved to a one-novel-per-block structure with additional “Planeswalker” novels (not to be confused

with the old-school novel Planeswalker) focusing on various new-era characters. After the decently reviewedAlara Unbroken and the flawed-but-somewhat-promising Zendikar: In the Teeth of Akoum, the second Robert B.

Wintermute block novel, Scars of Mirrodin: The Quest for Karn, received

disastrous reviews. Liliana Vess’s Planeswalker novel, Curse of the Chain Veil, got canned and Innistrad didn’t

receive a paper novel; its story instead was told throughThe Cursed Blade, an online epistolary novel / alternate reality game.

In recent years Magic has experimented with e-books, putting out The Secretist for Return to Ravnica and Godsend for Theros. Both

followed a serial distribution and payment structure (three parts for The Secretist and two for Godsend), letting people buy in for $1.99

a hit. Both books show severe dropoffs in the number of reviews from Part I to the next

(

The Secretist

and

Godsend

),

suggesting that second-part sales also went down.

Consider this a spoiler alert, and have an Orcish Librarian before you scroll down.

Both books also suffered from “What the nine hells?” endings. The Secretist, which built up nefarious plots and planewide social unrest, ended

with a half-morbid, half-wacky rally run around Ravnica that ended with Jace Beleren telepathically enforcing The Power of Friendship on everyone, a finale wickedly and brilliantly parodied by Inkwell Looter.

Godsend had Elspeth Tirel, whose life had been one massive Trauma Conga up to that point, finally toppled the usurper Planeswalker-god Xenagos, only to get shanked by sun god Heliod and dragged into the Underworld.

While the “Journey’s End” wrap-up column tried to spin this as Elspeth making the ultimate sacrifice for love of others, it had all the feel-good of a Michael Haneke film.

The Khans of Tarkir storyline will see no e-book; instead, its tale will be told through Uncharted Realms, the current home of Magic’s short stories.

The Magic Short Story

The original Magic short story was “Roreca’s Tale” by Magic

creator Dr. Richard Garfield, included in an early player guide. Two Magic anthologies appeared in 1995, while six more span the

years from 1998 to 2003, giving authors established and new their chance at telling Magic tales. The Shadowmoor “novel” was itself an anthology, and the

sheer variety of tales makes it unique among the game’s post-Time Spiral print offerings. It’s also a personal favorite.

Since June 2012, a more-or-less weekly Magic anthology series, “Uncharted Realms,” has appeared Wednesdays on DailyMTG.com. While the recent revamp of the

Wizards.com site has made it difficult to piece together the whole of the series, that’s what wikis are for. Thanks, MTGSalvation!

The Magic Comic / Graphic Novel

The link between comics stores and games stores is well-established (as seen onthis ancient AngelFire page), so it is unsurprising that Magic comics are out there. The first official Magic comics emerged in 1995 and 1996, a rapid

flurry put out by Armada / Acclaim. Later, in 1998, Dark Horse put out a series of Gerrard Capashen-themed comics.

In 2008 Wizards launcheda series of webcomic minis, beginning withThe Hunter and the Veil, that later were collected into two bound volumes with print exclusives. Also in 2008 was A Planeswalker’s Guide to Alara, a full-color consumer

version of Magic’s internal worldbuilding guide. Though the book itself was expensive to produce and didn’t sell well, it led to later versions being released online for free.

The most recent foray into Magic comics is the IDW series, which introduced Dack Fayden to the

Multiverse. While I haven’t seen anything about Dack venturing to Tarkir, the IDW comics have come with a series of promo cards, including Treasure Hunt

and Standstill.

The Magic Poem

A world without poetry wouldn’t be much fun at all, so it’s hardly surprising that a fantasy Multiverse would have plenty of examples. Cards have had

self-contained poetry from the start to the present, from Lost Soul in Legends to Magic 2015’s Geist of the Moors.

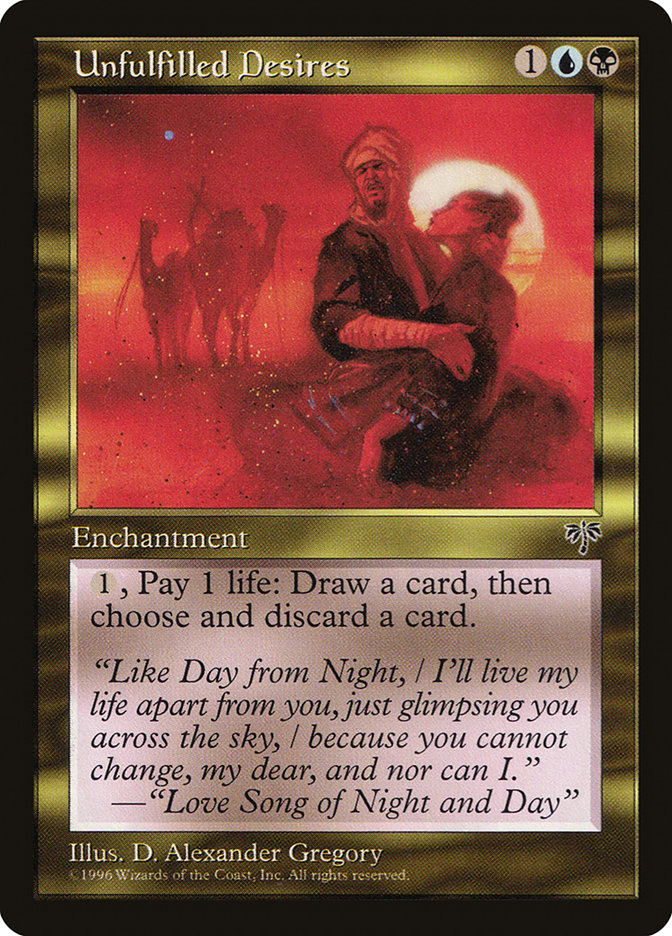

The most important piece of Magic poetry, however, is ” The Love Song of Night and Day,” a poem of Jamuraa, the place

where the Mirage set took place. Seventeen cards took flavor text from “The Love Song of Night and Day,” and when we at StarCityGames.com were making the

amazing playmat for Grand Prix Orlando, we made sure the Thespian’s Stage would perform “The Love Song of Night and Day” in the rotation.

Speaking of the Thespian’s Stage, The Theriad, seen in glimpses across the cards of Theros Block, was a modern Magic attempt to invoke epic Greek

poetry. Most of the cards are little-remembered even this soon after their printing because they are vanilla creatures, though the lean efficiency of

Swordwise Centaur and Oreskos Swiftclaw have given them a few fans. Also from Theros Block, Jennifer Clarke Wilkes contributed an in-plane ode to a winner

of the Iroan games, “I Iroan,” that deserves props for ambition

regardless of one’s opinion of the piece itself.

The Magic Video Game

The original Magic video game, set on the plane of Shandalar, didn’t have

much of a story: get cards, defeat wizards, and take down a nasty Planeswalker. This didn’t, of course, stop the game from being a lot of fun and featuring

cards such as Goblin Polka Band (with its random effect not easily replicated in a paper card

game, the Goblin Polka Band is a precursor of the random effects in Hearthstone).

The whole list of Magic video games is surprisingly long…and surprisingly

short on plot. The Duels of the Planeswalkers series, however, does a bit to rectify this. It’s introduced several characters who later made it into the

paper game, such as Ral Zarek and Kiora. The first Duels of the Planeswalkers (not the rename/redo of the Shandalar game, but the 2009 version) used Nissa

Revane as an adversary (and covered her up a bit because the ESRB threw a fit). Duels 2012 had the “gather your allies”

theme and one of the best trailer-opening lines Wizards has ever dropped. Duels 2013 and later

wove the video game story and “paper” story together, loosely for Duels 2014 (Chandra tracks a Planeswalker named Ramaz) and more tightly for Duels 2015

(Garruk, Apex Predator hunts you).

The Magic Film

…and here’s where Magic’s storytelling past and present give way to the future.

Here’s what we know so far

. Things have gotten serious, but there’s still no guarantee that a Magic movie will come out. There’s no trailer, no release date.

The other side of the coin: a Magic feature film would dwarf any other media foray Magic has ever made, not close. There’s a lot on the line here.

The short-term trend is for Magic not to try to make money off selling media to its fans, paradoxically enough. Uncharted Realms is free. The

Magic novels are kaput, again. The comics are in limbo. The Creative team is morphing and growing to adapt to two worlds per

year. Marginal items like Magic e-books — and yes, Vorthoses, we must have been marginal to lose them — get lost in such turbulent times. The film, for

all its potential pitfalls, gives me hope.

If a Magic movie gets tickets sold though, and Hasbro scores a percentage of the gross…

If Tamiyo and Sarkhan are the hot Halloween costumes a few years down the road…

If I don’t have to explain anymore what Magic is, because mass media will have done it for me…

…it all will have been worthwhile.