To start out the year, Sam Black made a huge splash with his article Make The Right Play For You, basically making the claim “arguing against trying to find the perfect play.” This is a very controversial claim mostly because of the current conventional wisdom of “there is the right play, and then there is every other play.” It took a week, but Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa jumped into the argument with his own retort defending the idea of the “right play.”

There is a reason that this has largely become conventional wisdom. Magic is a complicated game, but at its heart we can think of “good” Magic as something that we can identify. In some ways, it’s comforting to go over the play or plays that were made and try to find the right “one.” A few years ago, I wrote this:

Good Magic is this: play (or thought or preparation) that increases the chances of our victory. Good Magic has nothing to do with guaranteeing victory—we call that cheating. Good Magic has everything to do with making that chance as big as it possibly can be.

The concept of EV—Expected Value—is one that is so often bandied about in tournament Magic circles that most of us know it. Getting the highest possible EV is generally regarded as the most correct way to discover the "right" play. If you don’t know what EV is, in simple terms, imagine this. With all known information available to you (cards you hold, cards you’ve seen, current metagame), if you made a decision a million times, the EV is the "average" result of that decision. A play with a more successful average result has a higher EV—if you were to make that decision, you’d get a better result most of the time. It doesn’t matter if you don’t end up getting that better result or not in any specific moment but that on average you would have.

In essence, the right play is considered the highest EV play because that play is the one most likely to create the best result. Whether or not you get that result (say, a win) is not important. What is important is that you maximized your chance at the win given all the information at hand.

Analyzing whether a play is correct or not can sometimes be an almost Herculean task. Take for example one of the more famous games of Magic in the last few years, the semifinal match between Brian Kibler and Jon Finkel. Finkel doesn’t block a Wolf token and dies in a flurry of burn as a result.

Here is the match in question:

Many people thought that this was a clear indication of an obvious mistake by Finkel; obviously he lost, and he could have had two counterspells up (Negate plus Snapcaster for Negate) to stay alive or simply blocked and not have been in a position to die as he did. But actually figuring out what the “right” play is isn’t easy; there are an incredibly large number of factors to be thinking about to determine that. AJ Sacher goes into the complexity of this a little bit in an old episode of AJTV.

What do you need to determine in order to know whether it is a mistake or not to block the Wolf? You need to examine every possible combination of cards that Kibler could have (including the known information), know the likelihood of that particular combination of hands, and the result. Another way to think of it could be to create classes of cards and do the same thing with each class—what groups of cards could Kibler have that mean the play is certainly a win, certainly a loss, and gradations in between, with the chances of each occurring. By performing a little math you can figure out the high EV play, and in this case whether or not Finkel made a mistake. Even though Finkel himself reportedly later viewed the play as an error, it is worth noting that determining whether it is or not takes a great deal of work.

Sam Black’s claim about the right play is a little bit different than merely denying that there isn’t validity in finding the highest EV play and going for that play. Sam’s claim is that in the real world the optimal EV play in a vacuum might not be the optimal EV claim for you. He writes, "The fundamental point that I’m making here is that the correct play for you needs to take into account how you’re going to play from that point on."

The emphasis there is mine.

This point does potentially come with a drawback in that it could allow a player to be able to shut down conversation on the merits of a play. Potentially one could argue that the suboptimal play that you made was “correct” for you, and in so doing you’re denying that there is value in the discussion of the optimal play. This counterargument is in fact the basic argument made by Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa. The stakes on this are quite high according to PV, who writes, “I think this line of thought will result in worse play overall and might actually be detrimental to your growth as a player.”

I think Paulo makes a very good point about this. If you are shutting down the conversation about what the best EV play in a vacuum is, you are shutting down your development. In any particular situation, a greater understanding of what is the best optimal path matters. That situation could very well come up again, and being able to recognize that best play can make it easier to execute that play in the future, as well as help you understand how to maneuver your way toward good situations or away from bad situations based on that knowledge. There is a very real danger in failing to develop your game if you allow yourself to be comforted by the illusion that all you have to think about is "what’s the good play for you."

Sam brings up a particularly intriguing idea:

"Take a deck like Jund. Jund is a perfect example of a deck that different people are going to play very differently—it’s a midrange deck that can take any role, and different people are going to think of what they’re trying to accomplish with the deck differently."

He goes on to describe several specific ways that a different player might approach the deck and makes the argument that the deck can be piloted in different ways, in a sense making them different decks. This is certainly true, particularly for more powerful decks, but this also runs afoul of Paulo’s criticism—whatever kind of player that you happen to be has very little bearing on the ideal play.

This critical idea is a huge part of the concept in Mike Flores’ greatest contribution to Magic thought in his classic article Who’s The Beatdown?. Misassignment of one’s role in a particular matchup can be the most significant factor under your own control that leads to a game loss.

Using Sam’s Jund example, yes, a Jund deck can be played in a huge variety of ways. A big part of the reason it is able to do that is that the cards it employs are so powerful that there is a lot of play available in powerful cards. A card like Lightning Bolt is so good that it can be a part of a deck’s plan to control the board or a part of a deck’s plan to end the game. But with that kind of power comes many opportunities to make mistakes.

Owen Turtenwald had a lot of success with Jund during the pinnacle of that archetype in Standard, and despite a lot of people saying that there was little opportunity to leverage playskill when you were dealing with cards like Bloodbraid Elf and Tarmogoyf, somehow again and again Owen just performed much better with the deck than other people. A part of this has to be a question of choosing the proper role to take in various matchups and playing and sideboarding appropriately.

In a similar vein, a deck like Faeries during its heyday could also be piloted in a huge number of different ways. It is almost appropriate that the two writers disagreeing on this subject, Sam and Paulo, are considered two of the most talented Faerie pilots of all time. The ways in which you could switch gears with Faeries was remarkable; few decks have been as able to have such wildly different strategic moments than Faeries.

To shift to aggression or to shift to control—this decision was one that could occur much more often even within the same game in Faeries than in most decks. Watching Sam pilot Faeries in this era was a true pleasure, and at the same time during a PTQ in Chicago, I found myself hating the way that the deck played in my own hands. I was in the middle of a busy life at the time and didn’t have nearly as much time available to play Magic as I would have liked, and it felt like my opponents were largely very practiced with the deck. I was being outmaneuvered and outgunned, even by players I felt were worse than me overall.

The fact of the matter was that despite my feeling (and the general consensus) that Faeries was the best deck for that PTQ format (Block Constructed) it was certainly not the best deck for me. I could have put in the work to potentially get up to speed, but I simply didn’t have enough time.

I put together a true aggro-control deck (Merfolk) with ten counterspells, Sygg, River Guide, a tight curve, and a top end at Oona, Queen of the Fae, defeating three Faeries decks on my path to the Top 4 of that PTQ before finally being knocked out by a Faeries player who barely managed to defeat me by in his words "getting an incredible pair of topdecks." While I can’t be certain of the actual EV of my Merfolk versus Faeries, I’m still confident that Merfolk was a better choice for me even though I concede that Faeries was the better deck. I just intrinsically understood the ways in which I would need to pilot Merfolk, and I hadn’t built up the experience in playing Faeries to be able to execute the important decisions that would let me take advantage of Faeries.

Making sure that you make that distinction is important; even if you choose to play "the Merfolk" deck instead of "the Faeries" deck, you need to be able to realize that with the right training and skill the higher EV choice might be a different deck than the one you’re rationally choosing because of your own skills. It is inaccurate to say that Merfolk in this example was the better choice; it was only contingently better because of my own failings as a Faeries player.

It is the same thing when it comes to Magic play at the level of the game (as opposed to the metagame). Sam Black’s contention that there is a "right play for ‘you’" is opposed by PV largely because PV is arguing the point that we need to seek out that best EV play, that it exists, and that ignoring it is something you do at your own peril. But Sam’s point speaks to the reality that most of us are deeply flawed players.

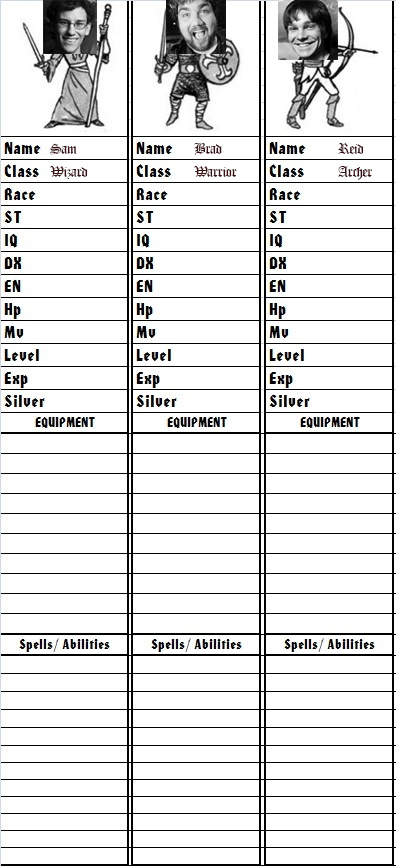

I was half-joking when I commented on PV’s article that we can imagine our Magic-playing selves—our inner Planeswalker if you will—as a character. Let’s take three Planeswalkers for example:

Each of these three Planeswalkers has a myriad of accomplishments that they’ve attained during their time playing the game. Certainly though I think we can all agree that these players have demonstrated wildly different skill sets from each other. While the various stats on the character sheet for Sam, Brad, and Reid are all left blank, it is basically because in Magic there are probably a wildly different set of playskills than perhaps we could have stats for.

It probably isn’t useful to imagine stats ranging D&D style from 3 to 18. In Magic, we don’t start out at "average" ability; instead, we start out at 0 and work our way up. Perhaps it is more reasonable to imagine our stats as 0 to 100. There is a huge range of Magic skills to think about, but they might include a list like this:

- Card valuation

- Pacing

- Combat

- Counterspell wars

- Life management

- Bluffing

- Strategic planning

- Mental stamina

We could probably go on and on. But simply put, our "stats" are not all the same. There are some skills and abilities in the game that matter more than others in more situations (combat is likely more valuable more of the time than counterspell wars as far as skills go). But even among the people you play with and that incomplete list of skills, you can probably give a rough ranking about who is better at what, and it is likely that different players will have different things at which they excel. In the case of Sam, perhaps he is better at card valuation than Reid or Brad. Perhaps Brad is better at combat. Reid might be better at pacing. I don’t claim to know where their relative skills are on any of these factors, but the fact remains that each of them might excel at some factor in their game more than the others, just as you and I do as well.

This is an important thing to consider when you’re thinking about tactical and strategic decision making while you’re in a game. There is something to the idea that Sam is bringing up when he says you need to know what kind of games you play best.

Paulo contests this with two examples.

First, one step down the slippery slope, he gives an example idea that many of us have heard before and might not sound too unreasonable:

"I like to be aggressive. When in doubt, I make the aggressive play."

Then to show the absurdity of the claim, he goes all the way down the slope (ad absurdum) to show how personal preference and style in strategic and tactical decision making isn’t a particularly sensible idea:

"I like to kill my own creatures. When in doubt, I use burn spells on my own guys."

At first glance, this actually appears to be a great rebuttal to Sam’s claim. As Paulo says, this second claim is clearly ludicrous on its face, so whatever someone’s "style" it doesn’t matter. There is a correct play—find it.

But I don’t believe that this logic actually holds under greater scrutiny.

We all hope to win when we’re playing tournament Magic. Getting that best possible result is important to someone who hopes to succeed in tournament Magic, whether it comes from selecting the best deck to play or making the right decision in a particular moment. Raising our EV to the highest level possible is a key part of doing this.

Unfortunately, it can be hard to quantify relative EVs of a few different decisions other than in the most clear-cut cases ("if this happens, it is truly going to result in a 100% chance of victory or loss"). A certain victory might be worth, say, a "1" and a certain loss might be worth, say, a "0," but what do we call a line of play that will "probably" result in a loss? Is that a ".2?" Even in the case where we can get that "1" and "0," accurately figuring out the chances for each proposition to occur can often be approximation compounded by further approximation, so we won’t have a fully accurate gauge.

All of that being said, as long as we realize that our quantification of the value of decisions is semi-arbitrary, we can still come to some useful conclusions.

Let’s recall the Merfolk/Faeries example I called up earlier. Let’s say for the sake of argument that my conclusions were accurate and Faeries was the best deck in Block Constructed. Merfolk in contrast was fine but not remarkably good compared to an "average" deck. Let’s give them these values:

Faeries: .75

Merfolk: .55

"Average Deck": .5

Now let’s also say that as a Planeswalker my character sheet shows that I just don’t have much aptitude at executing the decisions that a Faerie deck requires and I am much better at executing with Merfolk. Imagine my skill at Faeries is only at 30% proficiency for the deck. My actual real-life performance with Faeries won’t be the .75, above that it is in the "real world." As ideal as Faeries might be to select, if I’m not good at it, it will hurt me to select it.

Faeries at 30%: .2250

Merfolk at 41%: .2255

To get this result with Merfolk, I would only need to perform at "41%" proficiency to exceed my Faeries performance. Despite Faeries being a remarkably better deck, it is clear that our ability to execute the optimal plays in that deck will matter, even if we recognize that all of these numbers are simply abstractions to help us understand what it is we are looking at.

This can also apply to decisions at the level of a block. In a Sealed Deck situation, we might be faced early on with the question of whether or not to trade one creature for another or whether to race. Without knowing the contents of our opponent’s hand and library, this can be a hard decision. If our deck is relatively more powerful in a late game, the decision to trade and thus increase the length of the game makes more sense. If our deck’s late game is weaker, the opposite is true.

There is a huge variety of other factors, including our deck’s access to removal, evasion, cards that change tempo or affect life, and much more. Especially when you’re dealing with uncertainty and unknowns, you might quickly get to a state where the estimated Expected Value of one line of play versus another line of play could well be trumped by your skill at it.

Let’s imagine the following EV for each play:

Trade: ~.5

Race: ~.7

While we’re uncertain about the actual EV in this case because of the vast number of unknowns, if we estimate them at these arbitrary levels, we can imagine that there are certainly points at which choosing to trade is still better. If you are simply terrible at race situations, making the trade might be the right call for you. It is still important to acknowledge that the race is the higher EV decision, but that doesn’t change the fact that you could very well be more likely to lose if you make that call.

So let’s go back to Paulo’s two counterexamples:

"I like to be aggressive. When in doubt, I make the aggressive play."

"I like to kill my own creatures. When in doubt, I use burn spells on my own guys."

If we add to this the correct EV play, we might have the following three EVs (again, arbitrarily assigned values as best as possible) in a decision between possible strategies in a moment:

Play X, The Right Play: .8

Be Aggressive: < .8

Self-Destruct: near 0

If you are particularly bad at Play X, it still might be the right play for you if your ability to execute that play combined with the value of that play is better than your ability to execute an aggressive plan combined with whatever value that play is worth. If the relative values are actually quite close between the plays, you don’t even have to be that much better at being aggressive for it to be your best chance at finding victory.

Regardless of how good you are at making a self-destructive strategy happen, on the other hand, it won’t matter. There just is basically a near 0 chance that this is the right call because the basic strategy itself is of nearly no value. If the strategy were improved out of the realm of the utterly horrible, it could eventually rise to the point where it might be a more worthwhile decision than another strategy that’s better (in terms of EV) because of your own skill at that strategy

If we take someone like Paulo, who is one of the best players to have ever played the game, it is very likely that we might put his execution at some very high level. Whatever we call a "very high level" is arbitrary, but whether it is 90% or 99%, the fact remains that at that high level of proficiency there is little chance that any play other than the highest EV play would a better call for him. He is so good at executing various decisions that it really can be so pure as to find the highest EV play.

This is not the case for all of us though. One of the most interesting conversations I had at Patrick Chapin’s wedding was with a group of players discussing their respective play weaknesses. I was certainly one of the least-skilled players in the room and probably the least-skilled player in that conversation, but all of the other players in that conversation were among the best that the game has seen. Even so, they acknowledged weaknesses in playing, say, beatdown decks or control or other aspects of the game. There will be moments in each of their games and calls that need to be made where these weaknesses influence their decisions. At the highest levels of the game, this might be in the margin of inches (a .87 EV, say, versus a .86). Back on the earth where most of us live, they need not be that close.

I had a long discussion at a recent SCG event with William Jensen, Owen Turtenwald, Sam Black, Patrick Sullivan, and a few other luminaries. Owen was perhaps the youngest among us, and even he acknowledged that he could feel the differences in his mental stamina now compared to a few years ago. Sam agreed, saying he’d really felt it. "You just wait a few years," said Huey, "then get back to me."

Everyone laughed, but we all knew it to be true because we’d all experienced it. As we’ve aged, we’d all noticed the mental stamina we once had is simply not as easily relied upon as it once was. But we’ve all also gained other skills that we might place on our Planeswalker character sheet. It is however something that absolutely needs to be kept in mind.

Imagine for example you are in the finals of a PTQ, now playing in untimed rounds. You are both playing roughly the same decklist, a slow U/W Control list with only one Elspeth, Sun’s Champion and one Elixir of Immortality to finish out the game with. Each of you is over 30 life, and you’ve both already Elixired your graveyard into your library, so both of your decks are full of gas. Forty minutes in with neither of you having any active nonland permanents, you are given the following decision:

With fifteen mana up, you can cast your Elspeth into an untapped opponent with triple Dissolve to back your Elspeth up, but you also have a Sphinx’s Revelation, two Supreme Verdicts, and a Last Breath; you know from an earlier Jace (now under Detention Sphere) that the second to the bottom card in your deck is your Elixir of Immortality. Your opponent definitely has at least one Dissolve in hand and fourteen untapped mana.

Do you do nothing and discard a removal spell? Do you cast the Elspeth now?

In a game like this, it might be worth going all in on the Elspeth, partly in on fighting for the Elspeth, or simply waiting it out for longer yet and looking for a Jace to provide a potential threat at ultimate. My own instincts would be to almost certainly not go all in on the Elspeth since you actually might not win the counterspell war and if you do it simply might not matter because your opponent might mostly tap you down, resolve a Sphinx’s Revelation to refill, and overpower your Elspeth with Jaces and Detention Spheres and the extra cards acquired after the fight.

But if you are feeling the weight of that ten or eleven rounds before this one and you’re now certainly looking at a game 1 that could easily hit over an hour in length, if you know you won’t be able to make it through three games like this but your opponent seems fresh, making the other play could simply be the right call for you.

Magic is a damned complex game. In an incredible article by Richard Feldman, he talked about the myriad of small mistakes we can all make in any game. “Mike Turian was once asked if he had ever played a perfect game of Magic. He responded that so much a blink at the wrong time could disqualify you from playing a perfect game of Magic.” This is the kind of comment that makes it clear that there is a very real way in which even the best play in the game is only operating at level of execution likely far below perfection. Below that level of the game, most of the rest of us have to deal with the fact that we have weaknesses in our game. Even if for example the obviously right play according to EV might be right there in front of us, our human limitations might make another line of play more likely to help us accomplish a win.

We still need to heed Paolo’s advice and not neglect the value in determining what that "best" play is. He is right that we can’t allow ourselves to dismiss seeking to find the best EV play because if we do we will hurt our growth as players. At the same time it is important that we are able to honestly take stock of our ability to execute that play and if another path exists that might give us a better shot at victory to take it.

The trick is making sure you haven’t fooled yourself into taking the wrong line out of an arrogant overassessment of your skills or out of a lazy or fearful desire to play where you are most comfortable.