As a professional railbird for about seven years, I’ve learned a thing or two about the bad habits of TCG players. From mistakes to information leaks to breaches of etiquette . . . I’ve certainly witnessed more of each than I could ever remember, and I’ve got a pretty good mind for the stuff! Today I’m going to reflect on a few of the most common I’ve seen. Hopefully, you find it helpful—if not, then perhaps the personal anecdotes will tide you over.

Failure To Land

Not going in deep on this one, but man! People tap their lands wrong a lot in Standard. I imagine that fans of Modern and Extended have simply learned their lessons and developed the autopilot that keeps them from making this particular error so commonly. In Modern and Legacy such an error is usually punished with a loss, while in Standard it is seldom punished—but it’s still worth avoiding in order to dodge those rare moments.

It’s pretty simple really—autopilot to give yourself the maximum number of options. Standard has basically zero hate for nonbasics right now, so there’s no need to be tapping Hallowed Fountains when Islands will do. Sure, you’re not playing Celestial Flare, but there’s literally zero reason to not leave WW and UU open at the same time. The only person it could possibly affect negatively is your opponent, who has to puzzle through the entire range of potential plays you could make.

Don’t forget that the other side of the coin has merit however. Leaving open those Islands instead of Fountains on a turn when you’re absolutely certain you won’t need the Celestial Flare you’re holding could serve to disguise it on a later turn more effectively.

As formats change, you may need to adjust your autopilot—but it’s worth developing the ability to maintain an awareness of what your mana communicates to the opponent.

Lifelines

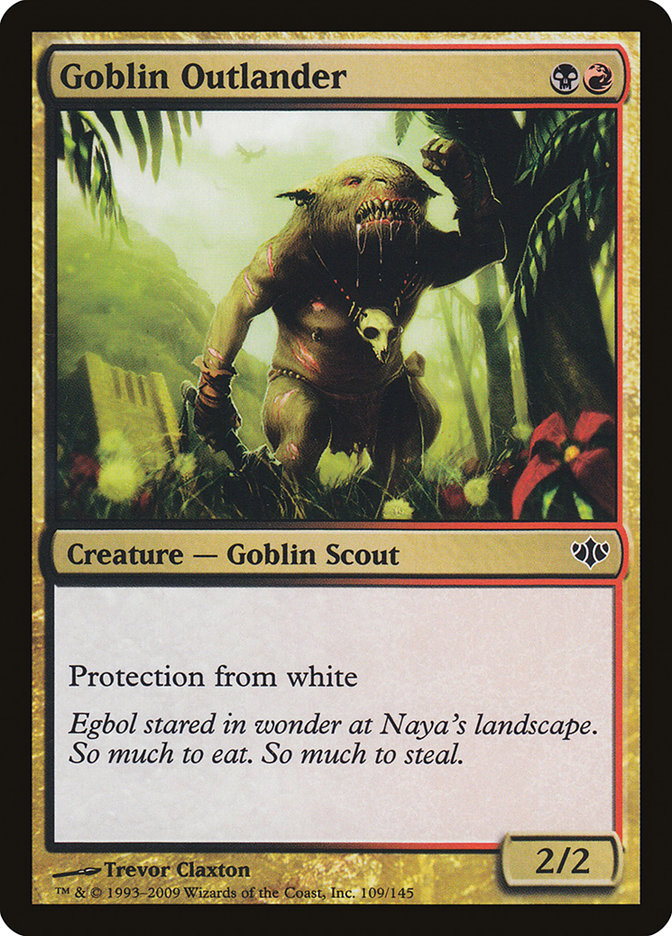

At my very first Pro Tour in Kyoto, I found myself mulliganing to six while playing Standard’s B/R aggro deck of the age. My opponent was on the draw and kept his seven, leaving me looking for a good six. I picked up my six cards and spotted three Goblin Outlanders alongside sufficient lands.

Against some decks in the format, this hand would be much worse than the average five—against others, it would be a snap keep.

So what did I do?

Well, I glanced at my opponent’s life pad. His last match was still there, recorded in two columns that featured his opponent taking a lot of damage and him taking very little—a one-sided beatdown. The first game started with his previous victim going from seventeen to twelve, while the second featured a drop from eighteen to twelve with my current opponent’s own life total increasing to 23.

Now today to you that probably means very little. But anyone playing a ton of Standard in that era, such as our esteemed content coordinator, would have likely been able to identify both of those openings—in fact, there was only one deck that could claim both play patterns!

The solutions?

#1: Turn 1 Goldmeadow Stalwart, turn 2 Wizened Cenn.

#2: Turn 1 Stalwart, turn 2 Knight of Meadowgrain, turn 3 Cenn.

I could continue, but I think the story tells itself from here. Would I have kept that hand if I was truly in the dark? Hard to say, but probably—I was much more mulligan averse back then than I am now, owing to me being stupider. My opponent however made it very easy for me. And that’s not the first time—another memorable incident involved me mulliganing a perfectly good hand full of shock lands in older Extended for six cards that could access Islands, as my opponent’s life pad gave away his Demigod of Revenges (and their accompanying Blood Moon).

Another tip regards how you track notes. Lots of players use their life pads to take notes, which is fine—when you Thoughtseize or see the cards someone sends to the bottom with Jace, Architect of Thought, it’s not very uncommon to jot them down. However, you should be aware that your opponent can see those notes too, which lets them keep track of what you know and remember significantly easier. Non-English speaking players can freeroll a workaround for this by keeping their notes in another language and using imaginative nicknames can work for everyone else.

End Of Match Etiquette

This is a tender subject. I’ve often said I could write an entire article on the do’s and don’ts of player conduct following a match whose result has been decided by time, and that’s probably true. For today, however, I simply have some guiding principles.

Check Your Ego

No one owes you anything—you’re playing a match of Magic with another person, and their goals, values, and beliefs may vary wildly from your own. I’ve known players who simply wanted a record that reflected the sum total of their effort, and that’s a totally reasonable thing to value. Just because I don’t find that important doesn’t mean I should scorn someone who does.

You can make day 2 but your opponent can’t, and the match is going to draw? Tough stuff, but no obligation to concede exists here for anyone based on those facts. It’s just a decision that you can discuss.

It’s A Two-Way Street

It goes without saying that the kind of person to ask for a concession should be the kind of person willing to concede if positions were reversed. And yet . . .

Before the change to Grand Prix made all 7-2s a lock for day 2, this situation happened much more frequently, and you’d hear people ask for concessions fairly regularly in such spots due to the high impact of byes. The most annoying variation?

“I will definitely day 2 with a win, while your chances aren’t good based on the math I can show you/the game state/whatever. Will you concede to me?”

“No, I’m not really comfortable with that, sorry.”

“Fine, guess we draw.”

Know what bugs me about this exchange?

The last line.

On the bubble with a round to go at States in Virginia (not the highest of stakes, no), I put my opponent to one life and nine poison with Thrun, Kessig Wolf Run, and Inkmoth Nexus in play to my opponent’s nothing—in game 3 on turn 5 of turns.

Not my best work, no. Anyway . . .

A win would put either one of us in a good position to Top 8 with a win in the following round. I asked my opponent if he was willing to concede, as I didn’t believe he could win the game and a draw would eliminate us both, and after some consideration he declined. I picked up the match slip, signed it 2-1 in his favor, and handed it back to him to be signed. He assumed I had erred, but when I explained that I was conceding, he didn’t understand. Why would I concede?

At the time, I explained it as such: “When you said ‘no,’ you took away my ability to win this tournament. I don’t have any reason to take that away from you.” As I walked away from the confused player, my roommate Forrest remarked upon what it said about the community that someone would be so surprised by my behavior.

From what I’ve seen, most opponents who decline to concede matches they’re drawing for no value do so because the nature of the situation makes them uncomfortable. It can be confrontational—many of them have had bad experiences in the past or just don’t understand the reasoning behind a concession from their position. If they’re not willing to scoop—if your politely spoken case doesn’t sway them—then there’s really no reason to not let them roll the dice themselves.

You’re not obligated to concede if your opponent declines to do so in this situation, but you should at least seriously consider it if you were willing to ask in the first place. Forcing the draw after they’ve declined to concede is basically just spiteful. Maybe your opponent was rude in the game, or you think the draw resulted from their slow play, or you have some other kind of history—maybe that spite is somehow merited. But at least own it for what it is.

I’ve known a few players who offer the opponent the match slip following the decline, imploring them to fill it out with the result they think the situation merits. This is a relatively effective olive branch.

Be Objective

At Grand Prix Houston, I found myself in a different situation with an applicable lesson. The final round saw me paired against MOCS competitor and Grand Prix seating neighbor Oscar Jones. Oscar was a lock for Top 64 with a win or a draw, while my math told me I was likely to Top 64 with a draw but not a lock. Neither of us could Top 32 without an event involving the deaths of several other competitors—pretty unlikely.

Upon reaching the table, I immediately offered the draw.

Many players are reluctant to roll the dice on their tiebreakers, but a stronger understanding of tournament math and EV will lead players to realize that these draws are often better gambles than playing! I looked pretty good to Top 64 with the potential to miss likely at 20% or lower. If I beat Oscar, then I’d be a lock to Top 64, but I’d have to be playing a completely different game altogether to think I was beating Oscar the 80% of the time required to make playing worthwhile!

I can respect the desire to put your destiny in your own hands, but that’s not always a rational impulse. Here, drawing wasn’t just the best thing for Oscar—it was also the best thing for me, making it an easy decision. When you’re trying to evaluate the merits of draws and concessions, relying on a rational evaluation of the situation will often be helpful.

Judgment Calls

If you’ve got concerns about how best to approach End of Match Etiquette from a rules standpoint, I’d encourage you to consult a judge—whether it’s in your spare time or during the event in question. Odds are if you’re going to time, one will already be sitting at your table. Our own William “Huey” Jensen wrote a fantastic article on the importance of judges to competitive play.

In addition to affirming that Huey is right on the mark, I’ll add that you should specifically consider judges to be a resource. They’re there for everyone, and calling them in order to clarify your own understanding will never be a mistake—in many cases it may protect you from making a grievous mistake. Personally, I always advocate that my opponent call a judge when they seem uncertain of an interaction or have any questions pertaining to the rules.

Pace Of Play

On that note, I want to talk a little bit about slow play. At Grand Prix DC a few weeks ago, I was playing David Ochoa during the Swiss rounds of day 1, with Ochoa on Sneak and Show while I was playing Four-Color Delver.

Game 1 saw me playing at a deliberate but consistent pace until the turn when Ochoa cast Show and Tell. At that point, I tanked pretty hard—I wouldn’t be surprised if you told me I spent over two minutes in total considering the sequence of the spells I’d cast in reply that turn. Obviously, this was the crux of the entire game—I wanted to make sure I got it right, and my single-minded focus caused me to lose track of keeping a reasonable pace of play.

After the game, Ochoa politely asked me to play faster, noting I had been overly slow. We had about 35 minutes on the clock at this time if I recall correctly, and we were both playing decks that would often be ending games in the first ten turns of the game. Realistically, we were in little danger of going to time even if we had to play a third game.

With this knowledge in mind, was his criticism of my pace and request that I play faster reasonable?

Yes! I was clearly playing too slowly! In fact, none of the above even matters.

Imagine that you could, a la Magic Online, track the amount of time Ochoa and I were spending on the game—it would probably have indicated I spent nearly twice as many minutes as Ochoa did, which is an unacceptable ratio considering that he wasn’t playing especially fast. The fact that Ochoa is competent enough to play well at a consistent pace doesn’t give me the right to use up egregious amounts of time when I encounter a tough situation. I have an identical responsibility to use time in the match fairly, and I failed to do so in that game.

Had he elected to call a judge to watch our match for slow play, I wouldn’t have felt offended at all—it would’ve been a very reasonable response to what he’d seen so far. As Huey noted, judges are there for exactly this purpose (among others).

Note that I’m not saying that you are obligated to play as fast as all of your opponents. A “reasonable pace” is more objective than relative—that’s why the risk of a draw isn’t a factor in the above scenario. An opponent playing at a lightning-fast rate can’t enforce their pace upon you, but you should be mindful of the amount of time you spend on your decisions.

Sideboarding Slips

No, I’m not going to lecture you on the merits of siding in all fifteen cards in order to disguise the number of cards you’re boarding in. Pretty much everyone knows that one and its merits, whether they employ it or not.

However, I see two other mistakes crop up a ton: oversideboarding in Constructed and undersideboarding in Limited.

Lots of decklists in Constructed are well tuned. That’s the beauty of the Internet age and the incredible number of high-profile tournaments going on. Most of the time players make their own adjustments to the lists they find on the Internet. The reasons vary: experience, inexperience, the bizarre human desire to make something their own. It’s pretty easy to wind up with a sideboard that has more cards to board in than cards to board out in or more cards to board out than it has to board in.

In my experience, the former is more common. Players go on a losing streak in tournaments or in testing, add a few cards to the sideboard to fix things, and fail to compensate with maindeck adjustments or more flexible use of the other slots. Then they get to the event and find themselves struggling to figure out those last few cuts in every round.

Meanwhile, the precise opposite occurs in Limited. A lot of players don’t bother sideboarding in Limited, just shuffling up and presenting after the first game. This attitude can sometimes invade the draft itself, with players choosing to hate cards or draft random rares when a card that might shine in their sideboard is sitting in the pack.

One of the best tips I can offer you for improving Limited sideboarding is to keep track of the cards that surprise you with their usefulness when you wind up playing them as your 22nd-23rd cards. Not only will you have learned when and where they’re at their best, but you’ll also be able to look out for them during the draft.

I hope my little walk down memory lane illuminated some of the lesser-known potholes out there in tournament Magic. By the time you’re reading this, Christmas will be over, and the excitement for a new year will have started to set in. I’ve got some spicy Modern content in the works, and I’m looking forward to having a fantastic 2014 on the West Coast!