As has been stated many times in the past, a significant portion of the Legacy metagame is made up of players who are illiquid in their deck choices due to confinements placed upon them by card availability restraints or “favorite deck syndrome.” Their inability—or unwillingness—to change decks week in and week out means that they’re stuck with outdated and suboptimal archetypes of which they’re intimately familiar. A truth that blankets all of Magic, but stands particularly strongly in reference to Legacy, is that deck familiarity is a potent weapon. Someone well versed in an obscure archetype is a real threat for competitive Legacy players if they’re not prepared themselves, even if that archetype is “bad.”

There is a strange plane of existence where these outdated and underpowered archetypes lie. It’s easy to call it tier three but that’s an incomplete writing-off of what is actually occurring. A more accurate description would be to say that this state of being is its own category of decks made up of numerous sub-archetypes. These decks aren’t the most powerful strategies the format has to offer; rather, they’re either the decks that appeal most to casual-competitive players, the decks that are easier to own (read: cheaper), or hit some nice intersection on the graph of ease of access vs. competitive potential.

Merfolk is a perfect example of the third form of influence, for example; it was once highly competitive and is relatively cheap to build. Thus, a good number of people purchased the deck at that time and then continued to play it because they owned it and knew how to play it. Or someone entering Legacy now may still (wrongly) believe it’s a viable deck choice due to its previous status as a top tier archetype, see how cheap it is to build, and purchase it on those bases. Whichever way they came by their situation, the fact of the matter is that they are stuck with it (or at least behave as such whether or not that is the reality or even their conscious perception). Writing this paragraph is inspiring me to put together a piece on this phenomenon using Merfolk as an example, but for now I should probably finish this article.

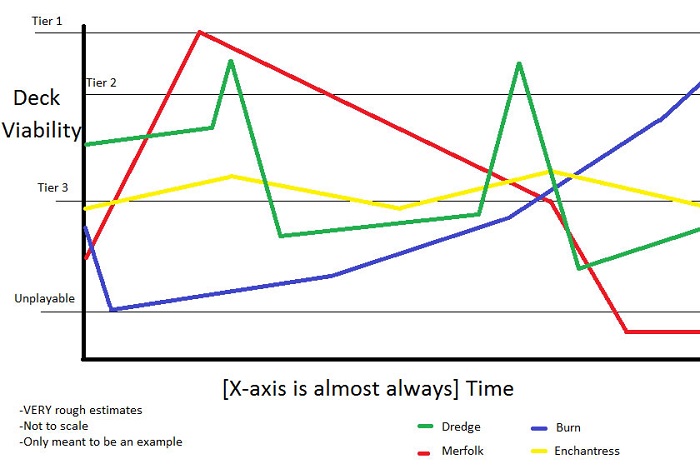

The reason you can’t simply label this group of decks as tier three is because of their violent and varying swings in both viability and popularity. Decks in tiers by definition are consistently in the same class as each other. This doesn’t hold true for the “Others.” Their paths differ by a wide margin, so trying to package them into a clear-cut tier of their own would have to involve redefining quite a few words.

MS Paint, hell yeah!

When you start to account for popularity fluctuations as well, it becomes even more needlessly complex. Then you have to account for regional biases and relative card availability changes, and you can see how it can get out of hand.

The important principle to recognize is the consideration that these decks make up a significant portion of any Legacy tournament. To say that you shouldn’t have lost because you were paired against Dredge and Dredge is really bad [right now, in general, against you usually but you changed sideboards, etc.] is to disregard what makes Legacy what it is. It’s like complaining that you only lost because your opponent played Terran in StarCraft. What did you expect them to play? Do you understand how this game works at all?!

I lost myself for a moment there. The point I’m trying to make is that there are quite a few of these types of decks, and they individually make up anywhere from a fraction of a percent all of the way up to fifteen percent of the metagame. That means that combined, “The Others” make up quite a large portion of any given tournament. Don’t be surprised when you get paired against Dredge “because it’s only 1% of the meta” when it’s actually just another one of the “Others” that really made up a third of the tournament.

While Merfolk is still easily played enough to be considered its own archetype, I include it in this category as it fits the criteria and is a good example of how widely varied this range of decks can be; it can go from something like Merfolk all the way to something like Kobolds.

For the purposes of this article, I gave myself two minutes to come up with as many “Other” decks as I could, as I knew that with unlimited time, I would try and dig through my fairly extensive history with the format and would spend a disproportionate amount of time working on compiling the list of archetypes rather than on the meat of the article. What I’m trying to say is that this is far from a properly comprehensive list; it’s merely a tool to use for our learning purposes. In fact, before reading my list, I suggest coming up with your own list. Give yourself two minutes to come up with as many “Other” decks as you can.

Once you’ve done this, feel free to continue, but don’t throw away that list.

I came up with this from my brainstorm session:

Dredge

Enchantress

Affinity

Sneak Attack

Hive Mind

Dragon Stompy

Painter

High Tide

Burn

Goblins

Merfolk

Breakfast/Life

Elves

Reanimator

Lands

Belcher

Kobolds

12 Post

Stax/Prison

The million crappy white creature decks

Some of these decks may stand out for one reason or another (Reanimator for likely being steadfastly tier 2 rather than “Other” or perhaps Kobolds because one may not think it’s played at all), but that’s largely beside the point. What I want you to do is to look for the things that make them similar, then for general observations about any over-arching differences.

The two biggest themes I’m able to pull out of this list of archetypes—besides that they are underpowered/inconsistent—is that a lot of them are pretty all-in on their game plan (lack of flexibility/versatility) and that they’re almost all strictly linear strategies.

My observations mostly pertaining to the general differences are about how varied the strategies are and how many different ones there are. Also that each item on the list has its own sub-list of variations. In fact, I can break up every item on that list into at least two versions without any real effort. With such a wide range of potential strategies and builds to be up against, preparing properly for all of them can seem overwhelming. With only 75 cards and limited playtest time, how could one possibly ready themselves for all of this?

The truth is that the format is so wide open, deck choice is influenced by so many more factors than other formats, and the card pool is so deep that it is impossible to be 100% ready for a Legacy event. Coming to terms with this is the first step; the second being to ask how you can maximize your limited resources (the aforementioned 75 cards and limited time) to be as prepared as you can possibly be.

While that as a whole is too large of a subject to fit into this article, the subject of this article is the largest portion of tournament preparation that isn’t already very intuitive and well-discussed. You see, you can play against a handful of decks in playtesting for a Standard tournament and be ready to go against 95+% of the field. That’s just not the case for Legacy, which makes the ability to remain liquid in your decision-making important.

Going over how to maximize the use of your time is easy enough. As it’s obviously unreasonable to expect anyone to playtest properly against every single one of these decks, any remote form of familiarity will be worth its figurative weight in theoretical gold. That is why I suggest against playing against any of these decks for an extended period of time (that time is better spent testing against the format’s major players such as BUG/Team America variants, Delver decks, Stoneforge Mystic, and so on). However, I highly recommend and strongly suggest looking at some decklists for each of these archetypes. It takes very little time, and just having a general idea of what could be in the opponent’s deck often ends up being invaluable in a tournament setting.

Without investing too much time and energy, you should be able to piece together what the decks are trying to do and how they plan on accomplishing that goal. Once you know that, you can find the focal point of the matchup fairly easily, which goes an extremely long way in figuring out how to play correctly. By default, they’re going to be more experienced with their deck than you are with yours, and almost assuredly better prepared for your deck than you are for theirs. This means that you can’t lean back on experience to carry you through a Legacy tournament like you could, say, with Caw-Blade in Standard. You always have to be actively thinking and making decisions on the fly. That’s what makes it such a great format (well, that and Brainstorm).

As for the deckbuilding side of things, that’s a bit more difficult to write about as it’s hard to do without getting deck-specific, thus excluding everything else.

While there are far too many heavily linear strategies to play dedicated hate for them all, there’s enough overlap between sideboard options that are efficient against a range of decks that you can formulate surprisingly high percentage jumps in any given matchup without rolling the dice by playing dedicated hate and hoping that the archetype you hated out is the “Other” deck that you run into the most. There are enough cards that are effective in a matchup without being hate at all, and it’s important to take those into consideration when making deckbuilding decisions.

Graveyard hate is the easiest example to use, so I’m going to use that to illustrate this idea. The percentages are completely made up with very little thought put into them. Just like all of the other quantitative things in this article, I’m just trying to show a concept in a more clear way.

For the sake of simplicity for this example, we’re going to pretend that Punishing Fire, Snapcaster Mage, and other things that use the graveyard which aren’t expressly mentioned don’t exist/matter. Also, we’re going to assume that each of these decks is exactly the same percentage of the metagame. In reality, you must weigh the percentages to get a proper calculation of their importance.

Nihil Spellbomb

90% effective against Dredge

60% effective against Reanimator

60% effective against Loam-based strategies

1% effective against Tarmogoyf

Tormod’s Crypt

90% effective against Dredge

70% effective against Reanimator (Daze/Pierce considerations)

40% effective against Loam (doesn’t cycle)

1% effective against Tarmogoyf

Relic of Progenitus

70% effective against Dredge (the mana is huge)

70% effective against Reanimator (extra mana outweighed by the draining effect)

60% effective against Loam

80% effective against Tarmogoyf

Surgical Extraction

60% effective against Dredge

70% effective against Reanimator

X% effective against Loam (I actually have no idea since there are just too many factors)

1% effective against Tarmogoyf

Extirpate

40% effective against Dredge

80% effective against Reanimator

80% effective against Loam

5% effective against Tarmogoyf

Scrabbling Claws

20% effective against Dredge

80% effective against Reanimator

40% effective against Loam

10% effective against Tarmogoyf

Scornful Egotist

0% effective against Dredge

0% effective against Reanimator

0% effective against Loam

0% effective against Tarmogoyf

I waited until after all of these made up statistics to tell you that this isn’t actually how card evaluations work. There’s no way to get an accurate “effectiveness percentage,” whatever that would even mean. Rather, it’s more about how you think the cards apply in the individual matchups. As in, you must consider all of the potential applications. Things can get murky when you also have to factor in whether the card you gave a 30% arbitrary effectiveness percentage, or AEP, is even better than the card you’re cutting for it.

Now imagine listing every possible application, not excluding Punishing Fire, Snapcaster Mage, Tombstalker, Past in Flames, Academy Ruins, etc. And then imagine weighing them all by predicted metagame percentages. And then imagine also considering your in-and-out numbers for each of the matchups to see when and where you’ll have room. Long story short, Magic is hard.

The main point of that section—that admittedly got a might convoluted—is that, while Nihil Spellbomb may be a better sideboard card against Dredge, it isn’t necessarily the best option for your sideboard card choice. Breadth of application often outweighs the strength in an individual matchup when it comes to sideboarding, especially in open formats.

I feel like I may have bitten off more than I can chew. I mean, in the sense that I was trying to discuss way more than one article can reasonably cover. I just wanted to get this all out there with plenty of time before Grand Prix Indianapolis. I suppose printing this as a Part 1 will suffice, as the ideas are all here. Then I can take my time and do a Part 2 correctly instead of rushing it out by an unreasonable deadline.

In the meantime, here’s a really good exercise to prepare yourself for the “Others” in time for GP Indy:

Take the list of “Others” that you came up with earlier on the article (just use mine if you didn’t make your own or if yours ended up being significantly less comprehensive than mine). Then, take a look at the list you were planning on playing in your next Legacy event (or the one you played in your last event). List the potential interactions/applications of all of your cards in every one of the matchups. If you’re thorough, you’ll be surprised at how many cute and obscure interactions you’ll find that can teach you about how your deck is capable of interacting with the metagame.

In Part 2 I’ll do an example or two of this exercise in a comprehensive breakdown. I also plan on further discussing how to increase your win percentage against a wide variety of archetypes without impacting your other matchups. I didn’t want to put this at the beginning of the article, even though that’s where it should logically belong since it is a type of “why you should listen to me” paragraph. But, because I didn’t want to sound like a snake oil salesman wheeling and dealing, I’ll just sneak it down here. The truth is, in my modern-career Legacy (not to be confused with my Modern career-legacy), my win rate against the most potent “Other” contenders is staggeringly high. That is to say, I’ve pretty much only lost to established, top tier archetypes. Despite very rarely packing any hate of any kind, I was able to cut through Burn, Dredge, Belcher, and Affinity regularly while piloting a wide variety of decks. I always tried to put myself in the best position I could against the field, and I did so using this quasi-hedging approach to create gameplans and tweak my builds.

If you’re willing to put in the effort to study it, Legacy can reward you greatly for all of the skills you acquire. You’ll learn lessons from this that will help you win a Standard match in a year without even realizing it. That is the beauty of Legacy. It’s Constructed in its rawest form.

Thanks for reading.

P.S. Can I just say how proud I am of the article title? I mean, I know that the “Others” isn’t a very descriptive or helpful term for the thing I was trying to talk about (and I probably should’ve put more effort into coining a useful term), but it just makes me happy on so many levels. Ok, I’m done now.