We’ve all seen it before. A player is way behind, dead in a turn or two

unless they draw the perfect card. They’re playing recklessly, attacking

when they can’t win the race. Or maybe they’re holding a counterspell and

just let their opponent’s third creature resolve in the hopes that they

draw a sweeper in the next few turns. An old friend of mine, Pat Fehling,

was famous in our play circle for doing this. We’d marvel at how terrible

he was and how he always managed to draw the perfect card.

“So, I was watching Pat’s quarterfinal match and he just spent the last two

turns chump blocking instead of trading, and then obviously he topdecks

Insurrection on the last turn to win the game.”

“I mean it’s Pat, so yeah of course he’s going to draw his one outer.”

“I can’t believe how lucky he is. Obviously, he then goes on to win the

PTQ.”

We spent years giving Pat grief about how lucky he was and how eventually

he would stop running so far above expectation. I think he enjoyed every

minute of it, because he intuitively knew a few things that we couldn’t

grasp at the time:

-

Many of those games would have been unwinnable had he taken a more

conservative line. -

The reason he so frequently drew the “perfect” card was because he

deliberately put himself in spots where some of his draws would be

extremely high impact. What looked like reckless play was in fact

correct since it effectively created more outs for him to draw.

A huge leap forward for my personal improvement was the realization that

you can’t win every game. Individual games of Magic have a degree of luck,

and sometimes, you need to be willing to take chances to give yourself the

best long run result. Take the following example:

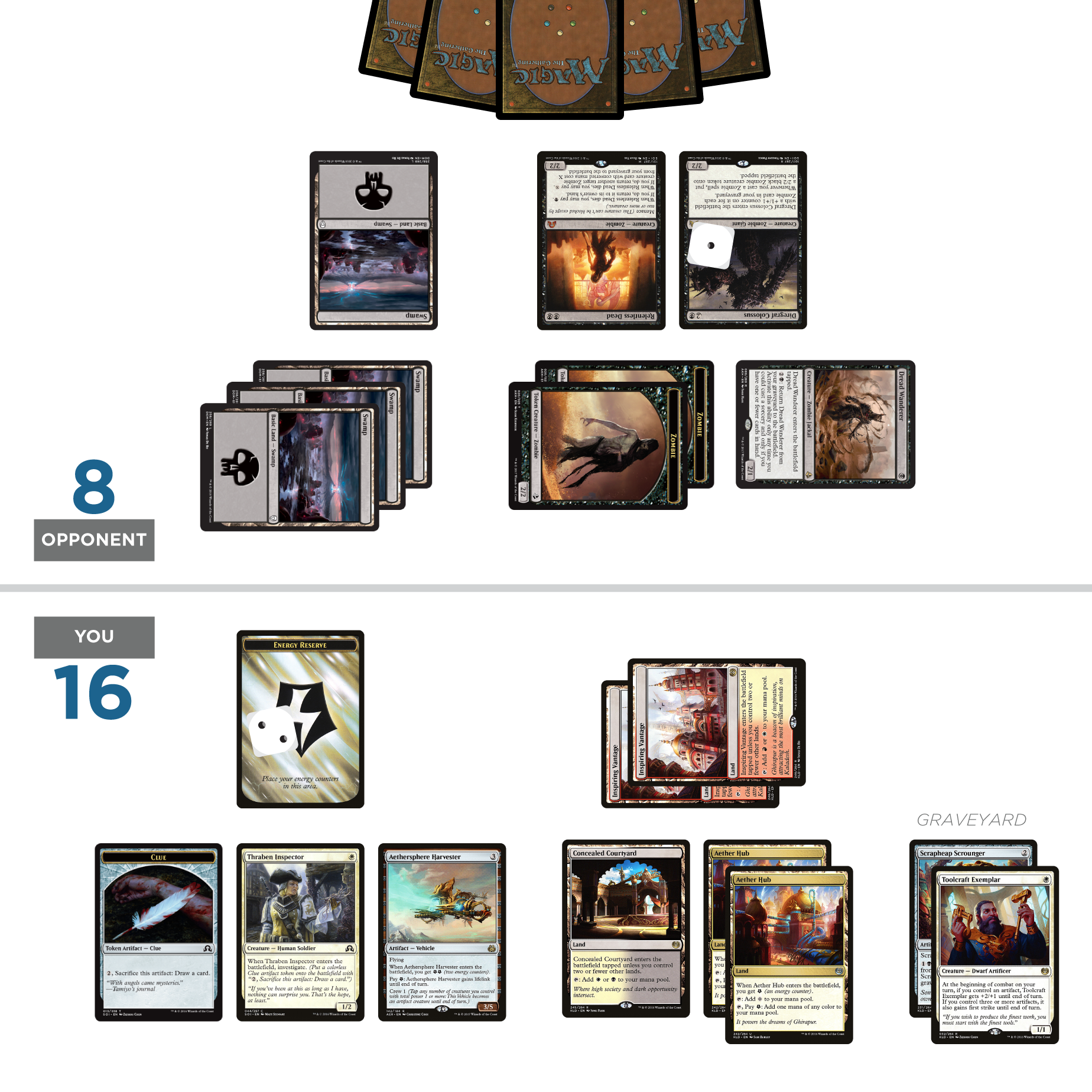

Your opponent did not play a land last turn. While you cannot be 100% sure,

you strongly suspect that they have at least one copy of Liliana’s Mastery

in their hand.

You basically have two options:

-

Attack with nothing, leaving back Aethersphere Harvester to make it

extremely difficult for your opponent to attack next turn. - Attack with Aethersphere Harvester.

A large percentage of the time, attacking with the Harvester leaves you

dead in two turns. You’ll gain three life, but they’ll get to counterattack

you for at least eleven so you’ll probably have to leave it back on the

next turn. Your opponent didn’t play a land last turn, so you’re fairly

certain they have five spells in hand. Even if they don’t cast Liliana’s

Mastery on their next turn, you’re still likely to be facing an even larger

horde of Zombies. If you choose this line, you’ll need to draw one of the

following to win:

- Unlicensed Disintegration (three copies left)

- Walking Ballista (two copies left)

- Pia Nalaar (two copies left)

- Archangel Avacyn (two copies left)

Unlicensed Disintegration and Walking Ballista both win the game

immediately assuming your opponent doesn’t draw an answer to Harvester,

which they haven’t had all game. Archangel Avacyn doesn’t win the game on

the spot, but she should make you a favorite to win if your opponent’s hand

is all threats and no removal. Pia is also an out most of the time.

Assuming your opponent attacks you with everything next turn and plays two

more threats, you can bring back Scrapheap Scrounger at the end of their

turn, you can use Pia’s ability to sacrifice the Clue token and her Thopter

token to clear the blockers and attack with Scrapheap and Harvester. Nine

total hits out of about 45 means that your odds of winning are a bit less

than 20%, since Pia and Avacyn don’t win a full 100% of the time you draw

them.

That might not seem like much, but compare that to the scenario where you

leave the Harvester back. A few years ago, I might have chosen this line

since it would give me the highest number of draws. The problem is that

Zombies is an extremely flavorful deck, insofar as Zombies just keep

coming. In this matchup, trying to keep our opponent’s battlefield clear is

nearly impossible. Your opponent almost assuredly has a ton of gas left and

can probably generate at least two additional threats each turn. There are

only two cards that you can draw that make you a favorite to win: two

copies of Archangel Avacyn. Barring that, you’re hoping for an unbroken

string of great spells to keep you in the game.

Sometimes your “out” is your opponent not having a key spell. This comes up

often against combo decks or other decks that generally have explosive

turns. Suppose that you are playing R/B Aggro against U/W God-Pharaoh’s

Gift:

Your opponent has a solid start while yours has been fairly anemic. Your

opponent just cast Champion of Wits discarding God-Pharaoh’s Gift. If one

of their two remaining cards in hand is Refurbish, you’re probably not

winning. Do you pass without playing anything so that you can Abrade a

potential God-Pharaoh’s Gift? Or do you cast Rekindling Phoenix and get

some pressure on the battlefield?

The problem with passing the turn in this spot is that you aren’t really

accomplishing anything. Your opponent is under no obligation to cast

God-Pharaoh’s Gift into your open mana. Since you’re not pressuring them,

they can just pass the turn back as they slowly develop their battlefield.

This is to say nothing of the fact that they might not even have a

Refurbish. In that scenario, passing the turn without doing anything just

gives them more time to find what they need.

The best thing to do here is cast Rekindling Phoenix and cross your

fingers. Sure, sometimes they’ll Refurbish a God-Pharaoh’s Gift onto the

battlefield and you’ll die horribly. For the times that they don’t have it,

you’ll be giving yourself a chance to win a game that would have otherwise

spiraled out of control.

Here’s another example from a game between R/B Aggro and a nearly

Mono-Green Ghalta, Primal Hunger deck:

You’ve already played a land, so your decision is between casting Kari Zev

or Unlicensed Disintegration. You suspect that your opponent might have

Blossoming Defense in their hand, since they didn’t attack with Servant of

the Conduit. However, they could be leaving it back to block a Scrapheap

Scrounger, which could also make sense if they didn’t have the Defense.

If you cast Unlicensed Disintegration on the Steel Leaf Champion and they

don’t have Blossoming Defense, you’ll be a huge favorite to win. Your

opponent will be at fourteen and you’ll get to attack with two Scrapheap

Scroungers, likely forcing them to block with their Servant. Your

opponent’s deck needs a critical mass of creatures on the battlefield to

cast Ghalta, Primal Hunger and overwhelm you with huge threats. If you

clear their battlefield this turn, it’s likely that your Glorybringer will

be able to handle their next threat and you’ll sail to victory.

If you cast Unlicensed Disintegration and your opponent does have

Blossoming Defense, things look horrible for you. You’ll trade your entire

turn and one of your best spells in the matchup for just a single mana

worth of effect. Your opponent will still be at seventeen, and your attack

looks much worse. They’ll probably be able to cast Ghalta next turn. You

won’t be able race, and you’ll have to draw another copy of Unlicensed

Disintegration immediately or you’ll die.

However, the alternative is just as bad. If you just cast Kari Zev, you

still won’t be able to profitably attack this turn. You’ll have to pass the

turn without doing much, and your opponent can just keep open a spare green

mana at very little cost to their battlefield development. You’ll be faced

with a similar decision next turn, and probably every turn for the rest of

the game.

The takeaway here is simple, though it took me years to fully internalize:

Don’t play around something you can’t beat anyway. Sometimes your

Unlicensed Disintegration will run right into their Blossoming Defense and

you’ll feel like an idiot, but sometimes it won’t, and you aren’t gaining

much by playing it safe.

This concept is related to the idea of playing to your outs. In both cases,

the main principle is that sometimes in order to win, you need to be

willing to lose.

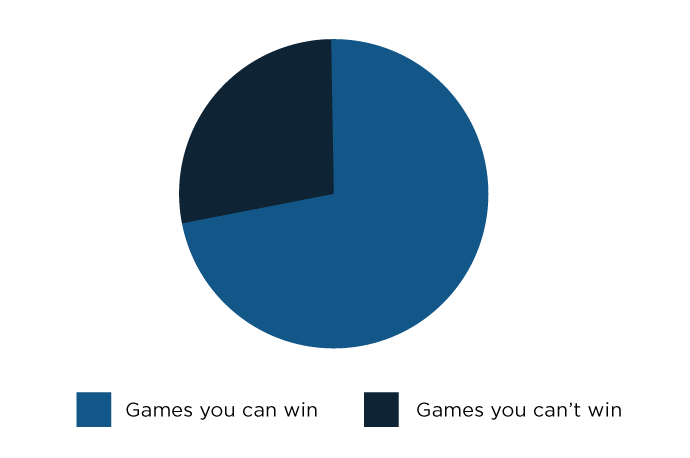

The first step is realizing that there’s a portion of this chart for which

you don’t have any equity. Don’t make sacrifices in the remaining portion

to chase after something that you can’t get. Instead, focus on winning the

games you can win.

Don’t Go Overboard!

An important thing to stress is that you still don’t want to take these

concepts too far. They only apply to a small subset of games you’ll play.

I’m not advising that you never play around anything; you should always be

cognizant of what your opponent might have.

The trick is figuring out how big each portion of the cart is. What I mean

by this is that in order to commit yourself to a risky line, you want to be

reasonably sure that you can’t actually win the games that you don’t think

you can win. Often, the only way to get to that level of certainty is to

practice. In the Zombies example earlier in this article, I know from

playing the Mardu side that it’s extremely unlikely that you’ll be able to

control the battlefield over the course of several turns. I only know this

because I had played that matchup countless times over the course of about

five months. In the game against Mono-Green, I know from playing the

matchup that the green decks rely on building a strong battlefield as early

as possible.

The ability to recognize spots like this has noticeably improved my game.

There’s still a fine line between taking calculated risks and just playing

recklessly, and I’m sure that there are times where I get a little too

aggressive. Still, just looking for those spots is a good exercise. It

takes experience to get a point where you’re confident in your assessment,

but once you get there it can be an extremely valuable still.