Modern is in a golden age.

Legacy is shockingly well-balanced for how busted so many of the cards are.

Even Vintage is continuing to evolve without its Restricted List growing to completely unwieldy proportions.

Standard?

Well, Standard’s not doing so well.

Don’t get me wrong; it is trending in a positive direction. Wizards of the Coast has a ton of outrageously brilliant, passionate, and talented minds on this. Maybe they have already course-corrected and nothing more need be done, except wait for the past year of cards they’ve already designed to come out.

Things could always get better.

There are plenty of spots and ways I may not see eye-to-eye with every aspect of Wizards of the Coast’s card design philosophy, and I certainly don’t presume to have all the answers; however, I propose that there are a couple of tweaks that would get at the root of some of the underlying “issues” with Standard, as of late.

What Are Those Issues?

While you can point to a variety of specific cards or choices, I think there’s an underlying theme that is contributing to Standard being more homogeneous that typically desired, with less room to evolve and less difference of feel from game to game, weekend to weekend.

Believe me, I get it. It is really hard for ten or twenty people to stay ahead of millions of Magic players jamming on the format; and that’s to say nothing of Magic Online players, which basically bring about a 10x multiplier.

We can do better, though.

To understand the current state of Standard, I’d like to turn your attention to the Legacy format. By most metrics, Legacy is far more diverse than Vintage, despite having fewer legal cards.

Why?

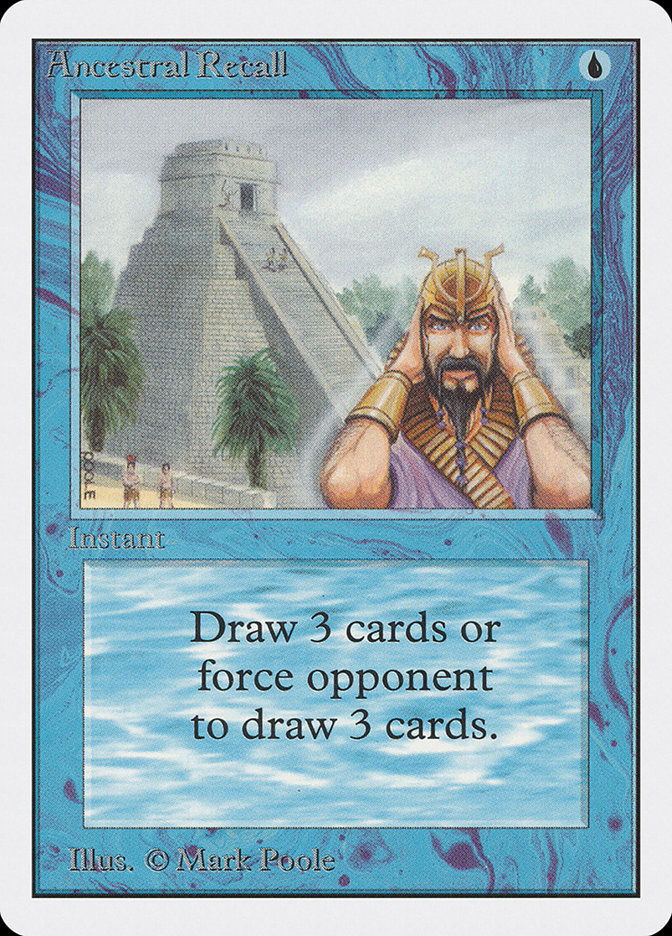

When you have a relatively small number of cards like Ancestral Recall, Black Lotus, and Mishra’s Workshop that are that much stronger than most of the cards in the format, they can form a narrow peak and warp the format around them.

And this isn’t to say that Legacy isn’t warped around key cards.

The difference is in how many cards are “banned” by Ancestral Recall, Black Lotus, and Mishra’s Workshop. Brainstorm and Force of Will may be overpowered, and they surely invalidate many other options because of their power; however, the difference in power level between those cards and Ponder, Counterspell, Tarmogoyf, Dark Ritual, Lightning Bolt, Swords to Plowshares; Jace, the Mind Sculptor; Hymn to Tourach, Wasteland, and so on is not nearly so great as the difference between Ancestral Recall and Mana Drain.

Mana Drain is absurd. We’re talking busted beyond belief. It would render any other format basically unplayable. And yet, in Vintage, it’s played in less than a quarter of decks.

And it’s not Mana Drain that pays the real price. When there are enough Mishra’s Workshop-level cards that Mana Drain becomes “an interesting option” rather than an “auto-include,” it actually makes the “Mana Drain Game” more interesting.

There is a sweet spot in between “Automatic Exclusion” and “Automatic inclusion.” That’s where the game is. That’s where the parts that make up interesting formats come from. The real cost paid for Ancestral Recall is in diversity among options that are interesting to consider. For instance, the following are format staples in Legacy, but most of these are extremely rare in Vintage:

If we look at every active deck on MTGGoldfish.com, as of this weekend, there are 27 nonland cards in Vintage that appear in more than a quarter of decks (Mana Drain appears in just slightly less than that).

|

Vintage Card |

% of Decks |

|

89.29% |

|

|

87.50% |

|

|

78.57% |

|

|

77.23% |

|

|

75.00% |

|

|

73.21% |

|

|

72.32% |

|

|

72.32% |

|

|

70.98% |

|

|

70.09% |

|

|

66.96% |

|

|

60.27% |

|

|

59.82% |

|

|

58.93% |

|

|

55.80% |

|

|

52.23% |

|

|

50.89% |

|

|

50.45% |

|

|

50.00% |

|

|

46.88% |

|

|

45.98% |

|

|

40.62% |

|

|

37.95% |

|

|

37.50% |

|

|

37.05% |

|

|

35.71% |

|

|

34.82% |

Maybe Vintage is a special case because it uses a Restricted List instead of a Banned List (setting aside Conspiracy and ante cards, Chaos Orb, Falling Star, and Shahrazad, which are all banned in all formats). However, that is a really long list of cards to actually show up 25% or more.

How does this compare to Legacy?

Well, the 46 cards restricted in Vintage put enormous pressure on the format. Once we remove most of them (Legacy does allow a few of them as four-ofs), the picture is understandable a fair bit different.

|

Legacy Card |

% of Decks |

|

60.65% |

|

|

57.74% |

|

|

56.77% |

|

|

54.84% |

|

|

50.32% |

|

|

38.39% |

|

|

36.13% |

|

|

31.94% |

|

|

30.97% |

|

|

30.00% |

|

|

29.35% |

|

|

27.74% |

|

|

26.45% |

|

|

25.81% |

|

|

25.81% |

|

|

25.81% |

|

|

25.81% |

There are 49 “real” cards banned in Legacy. Of those, 39 are among the Top 50 most popular cards in Vintage. A look at the remaining eleven cards in the Vintage popularity Top 50 gives us the first, second, third, fifth, ninth, tenth, and fourteenth most popular cards in Legacy, plus a couple of graveyard-hate cards and a couple of artifact-hate cards.

Okay, so Legacy has only seventeen cards appearing 25% or more, while Vintage has 26. So what?

Well, cutting off the sharp peak at the top results in a wider top of the pyramid. Without question, the best example of this is Modern, where the Banned List has been painstakingly cultivated over the years to a place where bans have become few and far between, yet the list of cards appearing in 25% or more of decks is a shockingly tiny six cards!

|

Modern Card |

% of Decks |

|

34.32% |

|

|

34.19% |

|

|

31.36% |

|

|

26.78% |

|

|

26.11% |

|

|

25.17% |

Remember, with 35 cards on the Banned List, Modern’s percentage of banned cards is actually pretty close to Legacy’s. However, the change in design philosophy after the first decade of Magic has gone a long way towards clipping the extreme peaks already. Overall, Magic’s power level has gone up, but the top tier isn’t quite so narrow.

Nonland cards appearing in more than 25% of decks are not inherently bad, but there is a balance to be struck. To really appreciate the current imbalance in Standard, however, we should first glance at the list of cards with popularities north of 25%.

Any predictions?

Vintage – 26

Legacy – 17

Modern – 6

Standard – ??

I’ll give you a second.

Remember, Standard has just three cards left on the Banned List, which is basically the same percentage of banned cards as the other formats (counting Vintage’s Restricted List).

|

Standard Card |

% of Decks |

|

48.88% |

|

|

42.74% |

|

|

41.62% |

|

|

38.83% |

|

|

37.99% |

|

|

37.43% |

|

|

34.92% |

|

|

34.64% |

|

|

31.01% |

|

|

30.45% |

|

|

29.05% |

|

|

28.77% |

|

|

28.21% |

|

|

27.93% |

|

|

27.65% |

|

|

27.65% |

|

|

27.37% |

|

|

26.26% |

|

|

25.98% |

While Legacy has more diversity at the top than Vintage, and Modern more diversity than Legacy, Standard is a giant step backwards. With nineteen cards appearing in a quarter of decks or more, Standard’s homogenization at the top surpasses Legacy and Modern, and is at least competitive with Vintage.

Dropping a little lower doesn’t exactly improve things for Standard, either. For instance, there are 34 cards that appear in 20% or more of Standard decks. In a format with four-ofs, that’s pretty wild, but even Vintage doesn’t have that many.

Perhaps, more tellingly, Standard has just fourteen cards that appear in 10%-20% of decks. There are significantly more than double that number of auto-includes. Compare this to the other major competitive Constructed formats:

|

Format |

Cards that appear 20% or more |

Cards that appear 10-20% |

|

Vintage |

31 |

19* |

|

Legacy |

20 |

20 |

|

Modern |

12 |

18 |

|

Standard |

34 |

14 |

*Vintage probably has quite a few more, but the MTGGoldfish list only displays the top 50 cards for each format. The 48th most commonly played card in Vintage was still over 11%.

Standard has vastly more auto-includes than interesting options. Its closest comparison is Vintage! By contrast, Legacy has a reasonable balance (color balance aside), and Modern has a shockingly good spread at the top.

What about lands? You’re going to mention Mishra’s Workshop and then not even list it?

It’s basically just more of the same:

|

Format |

Lands appearing in 20% or more |

|

Vintage |

15 |

|

Legacy |

14 |

|

Modern |

8 |

|

Standard |

15 |

It’s not just the relative lack of diversity among decks that leads to this. Lands, in Standard, get made with the same extreme spike at the top. It’s not a smooth distribution from Ramunap Ruins to Fetid Pools (not that it needs to be; it’s just more a consequence of how much Standard gets balanced around a relatively small number of power cards).

There is frequently an instinct among hardcore gamers to always advocate flattening out the power. While this is poor advice the majority of the time, there are times and ways and places where it can be useful. Remember, we’re not talking about wanting to change every Jack to a 7 and buff every 3 to 7. We’re talking about attempting to have a slightly flatter top, like we see in Modern.

While Modern has evolved with the help of dozens of bans, I don’t think an aggressive ban policy is what’s called for here. Rather, I think we’d see a noticeable improvement with a little bit of a shift of design philosophy on the top-tier cards the sets and metagames are designed around.

First, a disclaimer: it’s very possible that there are other meta-considerations that might play a large enough role as to need to be factored into any possible design shifts. It’s not just business model stuff, either. There are a lot of different ways to play Magic and a lot of different Magic players. Not every single design decision is going to be about optimizing the Standard experience.

With regards to the business model stuff, one might argue that the key mythics are crucial to making sure a set sells. However, if you look at recent sets, a lot of the most pushed cards weren’t mythics. Smuggler’s Copter, Toolcraft Exemplar, Glorybringer, Longtusk Cub, Rogue Refiner, Ramunap Ruins…the list goes on and on. However, when you look at the singles market for some of those sets, it’s not always pretty, and that’s partially because of how many fewer of the cards are getting played. Besides, banning cards in Standard is really bad for business.

Felidar Guardian was a mistake, not because of being too pushed, but because of missing an interaction. And while you’re always going to miss stuff, there are likely a variety of measures in place to alleviate the risk of such an oversight moving forward.

As for Smuggler’s Copter and Aetherworks Marvel, it’s tempting to write them off as “obviously overpowered.” After all, they have proven to be “overpowered” in such an “obvious” way that both were discussed as cards that might realistically get banned eventually. However, I believe they are both symptoms of the same disease.

Smuggler’s Copter being that pushed ensured that Vehicles would show up in top-tier play.

Aetherworks Marvel being that pushed ensured that energy would show up in top-tier play.

These are not isolated incidents.

The problem isn’t wanting to ensure the new mechanics show up. It’s a great goal, particularly when you believe in the mechanic’s play pattern for Constructed. I believe the problem stems from attempting to brute-force the top with relative power. The rate on these cards is whatever. While it’s useful to evaluate the “objective” power level of cards, it’s really not that big of a deal, compared to how they fit into the format.

While there is some of the “less Kings and more Jacks” experience being sought, I would like to see more of the new Kings made with built-in weaknesses that few (if any) cards or decks can exploit. Of course, with careful planning, a new mechanic may be the perfect foil, or something the format has been missing gets added.

It looks to me that Kaladesh tried to do this with artifact destruction. There was noticeably poor artifact destruction when the set first came out, but the quality grew and grew until we reached this spot where Abrades, Dissenter’s Deliverances, and Cast Outs are available to anyone who wants them. Unfortunately, it’s not like Smuggler’s Copter, Aetherworks Marvel, and Torrential Gearhulk are actually stopped by Revoke Existence.

For sure, it can help, but that’s not really what those cards are about. Wurmcoil Engine gets beaten by Revoke Existence. Icy Manipulator gets beaten by Revoke Existence. Ensnaring Bridge gets beaten by Revoke Existence.

What Do Those Cards Have in Common?

Investment.

You know what doesn’t involve a lot of investment?

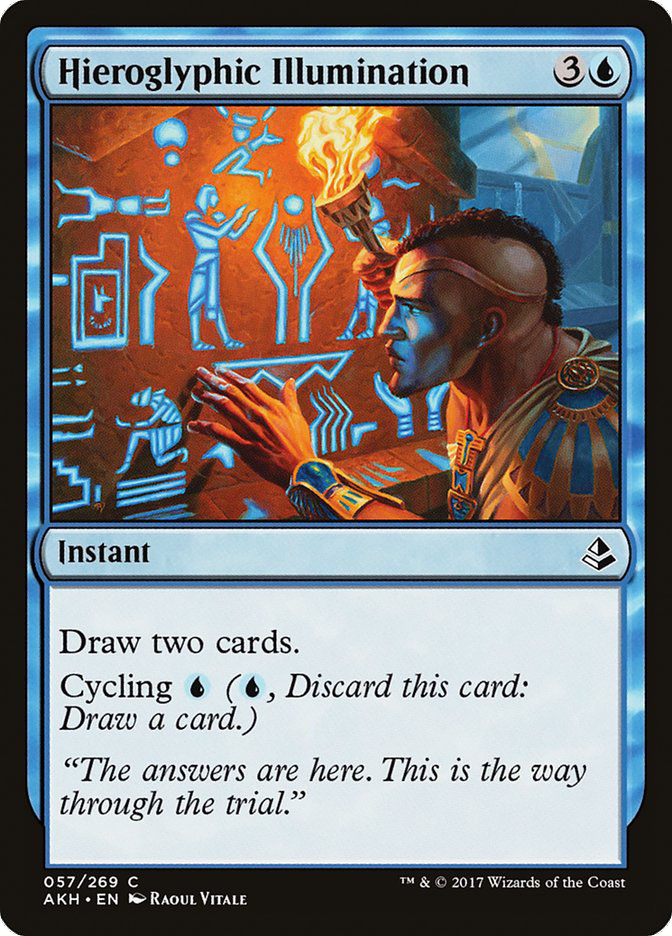

- Cards that cycle for one mana

- Cards that die into card draw or go back to your hand

- Cards with enters-the-battlefield triggers or haste

- Cantrips

- Untapped lands with low opportunity cost

- Cards that cost two or less

I’m not saying you shouldn’t make good cards with these traits. Rather, there needs to be a balance, not only in how many of the best cards have these traits but in how much of their power comes from these traits versus how much is investment. The majority of the best cards involving investment leaves more room for counterplay, for printing more cards later that shift the balance of power.

Even cards with haste, cards that make extra material, cards with immediate impact, can be made in such a way as to have a meaningful amount of the card’s power level come from investment.

When you want to attack with Butcher of the Horde immediately, you invest a creature sacrifice. When you want that extra 3/4 Roc, you invest whatever resources into the attack just before. Even Mantis Rider was an investment in a world with so many great one- and two-mana ways to answer it; importantly, however, an unchecked Mantis Rider isn’t immediately game over.

If you don’t have an immediate answer to Longtusk Cub, a high percentage of games will spiral out of control. And it’s not just that Longtusk Cub requires so little investment; so much of the card’s power comes from its ability to snowball.

Goblin Rabblemaster was unbelievably snowbally, and I think too much so. However, at least it cost three instead of two, and at least it puts all of your Goblins into harm’s way, building in a natural safety valve for getting out from under it.

If you don’t have an immediate answer to The Scarab God, a high percentage of games will spiral out of control. And yet, it asks so little investment of you. Like so many other designs, I think you gotta ask yourself, “How interesting is the game next turn?”

I’ve used this example before, but I think this really is the poster child for where there ought to be more investment. A 5/5 that dies back to your hand and is easier to cast than Weatherseed Treefolk is already a lot, and that’s a pretty absurd floor for a card with many other abilities.

The Scarab God promises cool and unusual game states. What am I going to get back this turn? What are the consequences of these creatures being 4/4s instead of their usual size? How can I leverage this scrying and life loss for more advantage? How can I take advantage of all these Zombies?

The reality, however, is that much of the card’s power is tied up in its outrageous rate, it dying to your hand, and the activated ability functionally being not only a source of card advantage but a source of mana advantage, battlefield advantage, selection, disruption, and more. You don’t even need to invest in having sweet creatures to get back. You can just punish your opponents for having played sweet creatures.

Imagine if The Scarab God could only target your own graveyard?

What if The Scarab God wasn’t bigger than most other five-drops to start with?

What if more of the power of The Scarab God came from the scry and drain ability, but the dies-to-hand ability require more investment?

Morphling does require a little bit of mana investment to give yourself insurance, and Prognostic Sphinx does cost you resources, but both of these cards are extremely repetitive and really don’t require that much investment besides the initial startup cost (and both are under-statted, as you are paying for their outrageous abilities).

Imagine if The Scarab God cost B or 1B or UB to make indestructible until end of turn, or whatever. Do you still cast it Turn 5? Now we’ve got ourselves a game. The real version doesn’t make you pay for the rebuy unless you “already got value” from it. It’s your opponent who is being asked to make the investment.

In fact, I would go further. What if the aforementioned indestructible ability tapped The Scarab God and made it not untap during its controller’s next untap step? Now the game is progressing and is meaningfully different not only this turn but next. When and whether to kill The Scarab God is a much more interesting question under such a schema. You could also generally charge less for such an indestructible ability. (Not that they were actually charging much for The Scarab God’s text…)

This isn’t to say there isn’t a place for extremely resilient forms of inevitability that get the game over with. Morphlings and Aetherlings are one way to go, and untargetable threats like Sphinx of Jwar-Isle are another.

These types of threats are very different from The Scarab God. They aren’t inherently dominating the battlefield or taking over the game. They are merely tools for leveraging a superior position into a win. They have some influence over the battlefield, but substantially less than their peers from an efficiency standpoint.

The Scarab God is closer to Prognostic Sphinx, but with a much higher floor. And while I deride the card, there is a lot to like about the card and the general push towards cards that do something. Torrential Gearhulk, by contrast, is boring. So little of the card’s power is as an interesting game piece. So much of it is the cantrip Regrowth and the free Black Lotus to cast the card.

Grave Titan was outrageously pushed, and the enters-the-battlefield trigger meant you were often getting the better of it, even when someone could kill it. However, Grave Titan itself was an epic game piece with high stakes. Casting a six-drop during your main phase is a much bigger investment than Torrential Gearhulk’s flash. Again, I’m not saying Grave Titan wasn’t overpowered. I’m just speaking to investment, including the cards specifically trying to “pay you” even if someone has counterplay.

Of course, basically all of these cards are better ways to win than Sphinx’s Revelation. Burying someone under an enormous amount of card advantage, while also removing counterplay in the form of life total? Well, it doesn’t really make the game all that much more interesting afterwards.

I’ve been a bit outspoken about Pull from Tomorrow, but just to make sure it’s considered in the scope of this topic, it is my thesis that if Pull from Tomorrow isn’t a problem, you’ve got other problems. Start on Divination.

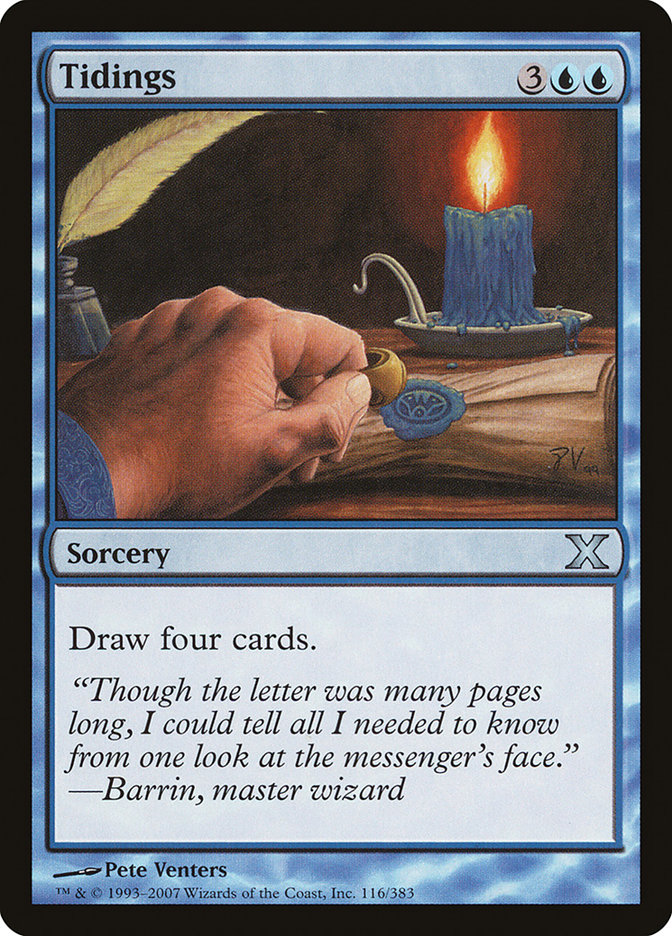

Is it worth paying two extra mana for two extra cards, swapping a Divination for a Tidings? It’s a gamble, but it’s more power if it pays off. You’re going to feel the pain every time you’ve got just three or four mana.

What about Jace’s Ingenuity versus Tidings? For an extra mana, you get the flexibility of casting it instant speed. However, if you’re willing to make the investment, you get an extra card.

When we turn back to Pull from Tomorrow, it should be easy to see how much less game there is. However much mana you have, you can convert it all! Why invest anything in your main phase? Let’s just get everything and rely on the card to be counterbalanced by Toolcraft Exemplar and Longtusk Cub!

See, this is what I’m talking about. This isn’t using cycling to get some Shatters into people’s maindecks, but at a cost in efficiency and tempo. This is just resource manipulation seeking to minimize investment risk.

I’m not suggesting a refocus on investment solves everything that ails Standard. However, I do believe it would be a major step in the right direction, and one that one lead to dividends year after year. There are plenty of areas of design philosophy would could debate that might improve some aspect of the game, but without continued returns year after year.

For instance, consider the five-color fixing in Standard right now.

I think Standard is suffering as a result of the excessive support for five-color fixers compared to duals. The first “pushed” five-color fixer you make is one thing, but the moment someone gets two, it completely changes the equation (as we saw with Undiscovered Paradise and Gemstone Mine in Five-Color Green, and with Vivid Lands / Reflecting Pool in Five-Color Control, just to name a couple).

However, whether these are “mistakes” or “differences in design philosophy,” they are really just minor tactical discussions in the greater conversation about how much of a price you pay for the added flexibility of other colors, compared to just playing two colors like a “normal deck.”

And of course, this is just an extension of the greater discussion about investment. To develop some heuristic such as “don’t make two good five-color fixers” is a short-term remedy that will eventually break down. Besides, when do they “get good?”

It’s not like Survivors’ Encampment or Cascading Cataracts or Unknown Shores is the problem. When the cost of adding a fourth color is putting a single Swamp in your deck, it may very well be an unclear and challenging problem, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s one with a lot of granularity, a lot of different ways for the format to go.

Magic is about taking risks to get rewards, making decisions based on your strategy in the game, and the tactical demands of this particular encounter. These are the kinds of investments I’d like to see emphasized with regard to how many opportunities for these experiences there are, how much the sum total of them are significant, and how diverse a mix of puzzles there is to solve.

I would love to hear any suggestions, ideas, feedback, or whatever in this vein. Magic is an amazing game, and part of why it continues to flourish, 25 years later, is just how much the community contributes perspectives on how to continue to improve the game.

Thanks for taking the time.

TL;DR

- I would slightly flatten out the top of the power curve.

- Decrease the emphasis on one-cost and two-cost threats that generate snowballing advantage.

- Increase the amount new mechanics are propped up by contextual strengths, while decreasing the subsidization from rate and avoiding opportunity cost (Rogue Refiner and Glimmer of Genius, for instance).

- Build in more potential weaknesses and opportunities for counterplay, with plans for how to eventually leverage that to change the format.

- And most importantly, increase the percentage of the best cards’ power that comes from investment.