While I was off doing coverage of Grand Prix Las Vegas (hope you tuned in!), I asked fellow Rules Committee member Alex Kenny to sit in for me. You don’t often get to hear too much from Alex directly, so I figured that while I was busy with the largest-ever TCG tournament, the opportunity was ripe for you to appreciate the power of Alex’s brain and demonstrate why he’s been an RC member since the early days of the format. Enjoy his theorycrafting, and then enjoy the deck he makes as an example.

-Sheldon

A tyrannical Grand Arbiter, looking for a bit of entertainment, summons three political prisoners to his throne room. The prisoners are seated, tied and bound, in single file in front of the Arbiter so that prisoner A is looking directly at him, prisoner B can see the back of A’s head as well as the majestic throne, and prisoner C can see all of A, B, and the Arbiter.

The Arbiter announces, “At the back of the room, I have four hats, two white and two blue. I am going to place one cap on each of your heads, and the fourth cap will be kept hidden. After that point, any one of you may say one word. If that word is the color of that person’s cap, you all are free to go, but if that person is wrong or if you attempt to communicate in any other way, you will all be executed tonight.”

“Within eighteen hours, or within 26 hours if the date is between one day before or two days after a civic holiday and the presiding custodian has received a written alert as per C.R. 10 §903.5(c)(1)(d),” adds a greyish homunculus. The Grand Arbiter smiles slightly and sighs in satisfaction. He motions, and a cap is placed on each prisoner’s head.

The prisoners know each other from the gulag, so each knows that the others are intelligent. The Arbiter is as well, though, so none of the prisoners would dare to cheat. Also, none of them would risk their life on a gamble, so none of them would be willing to guess, and they can’t see their own cap. No matter how the caps are arranged between the prisoners, how do they escape their predicament and earn their freedom?

Working backwards is enormously important to the field of game theory, where it’s termed “backward induction.” It’s often by far the easiest way to solve problems of all sorts. To use backward induction, start thinking about your problem at its end state, and if it’s the right type of problem, the solution will be much easier to discover. As an example, let’s sit down for a game of Magic.

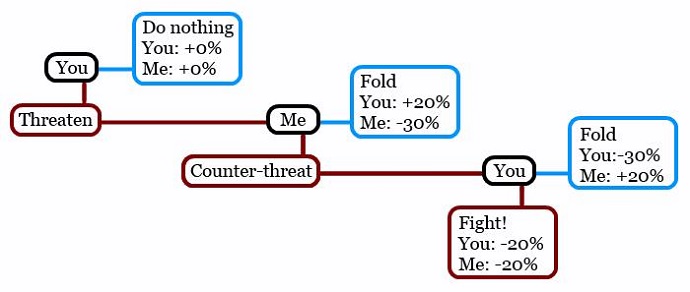

The game is down to three players, and you’re pondering the Path to Exile in your hand. I’m about to declare attackers, but I haven’t decided who to attack yet. You’ve got the option to threaten me: “If you attack me, I’m going to Path your biggest creature.” You figure that if I fold and attack our mutual opponent, then your chance of winning the game will go up 20% while mine will fall 30%. I have the option of making a counter threat, though: “Use that Path to Exile on his creature right now or I’ll attack you with everything.” If you comply, you’re down an answer card and I can still attack whoever I want, so now I’m gaining the 20% and you’re losing the 30%. You can stand your ground instead, but I’ll make a big attack at you and lose my best guy, so both of our chances of winning fall by 20%.

What do you do, and what is likely to happen?

Situations in a real game never happen exactly like this. Knowing those true numbers is impossible, thanks to all of the hidden information in the game of Magic and the unpredictable human factor. In comparison, this problem is very simple, and you’re probably already working on solving it, laying out all of the paths that the politics could take. That’s a totally legitimate way of solving this, but if you’re already in the habit of working backwards (or if you’re metagaming this article), you’re probably already done. Let’s take a look at this problem in flowchart form and practice some backward induction:

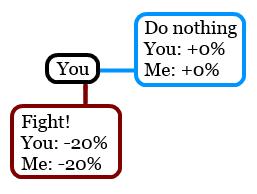

Start by thinking about the furthest endgame state, when everything went wrong. If you’re in the position of starting all out war or giving in to the counter threat, what do you do? Clearly -30% is worse for you than -20%, so you’d stand your ground every time. If the game gets to this state, both of you are getting -20%. Taking a step back, to get to that state I would have had to make a counter-threat in the first place. Is that something I would do? I can ignore your option to fold since I know it’s better for you to refuse instead, so that’s what you’ll. This means that my choice is simple: fold or fight? Just like you -30% is worse than -20%, so my only reasonable option is to make the counter-threat and start a conflict.

This brings you back to the original question: is it a good idea to threaten me with your path to exile? Thanks to our calculations, the problem is now really, really easy.

A strange game.

Clearly, it will end up worse for both of us if you make the threat and start a fight since that will allow player three to just sit back and watch us destroy each other.

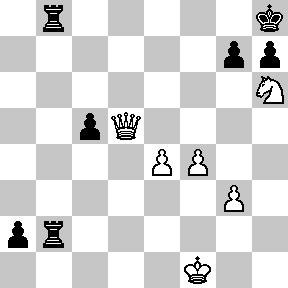

That was about as simple an example as possible, with no real decisions to make. How about a nice game of chess? Working backwards is perfect for a game like chess since there is no hidden information and no randomness. Nothing can disrupt your plan if you find a series of forced moves and don’t make any errors. Here’s an example problem:

White to move.

You’re white, and you’re in a bit of trouble. If black gets another free move, you’re toast (black’s pawn promotes to queen and all you’ve got left is a desperation queen sacrifice for one last turn). This is a hard problem if you’re not very familiar with chess. Fortunately, this position reminds hypothetical you of a tricky checkmate that might be available here:

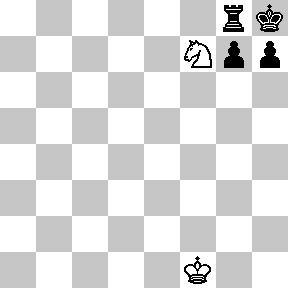

Smothered mate.

Now you’ve got a desired endgame to work from, which will make the problem much easier. All you have to do is work backwards and figure out how to force the pieces to be where you need them. (The solution to this one is at the end of the article.) It’s sometimes said that chess grandmasters can think a dozen or more moves ahead. It’s much more likely that they’re actually thinking a dozen or more moves back from some desired board state and finding all the necessary moves to get there.

Finally, back to the Grand Arbiter’s hats:

Prisoner C is staring at two hats. There are two endgame scenarios for her that are equally likely: she knows the color of her hat (if both of the hats she sees are the same color, hers must be different) or she doesn’t (if the two hats she can see are different colours, then there are still one of each—one on her head and one unused). If she knows the color of her hat, the game is over, as she says the word and the prisoners are free. Working backwards, what must be true if she doesn’t know her color, again? Prisoner B waits a few moments just to be safe and then says whichever color prisoner A is not wearing since prisoner C’s silence means that they don’t match.

Backward Deckbuilding

Working backwards is great for finding lines of play through complicated board states, but it’s also a very powerful tool during deckbuilding. Whether you’re playing competitive tournament Magic or you’re at the kitchen table, every deck has (or at least should have) a clear game plan, and working backwards makes sure that you don’t add too much unrelated chaff. If you want your new deck to be as streamlined as you can make it, start from the top.

First, find your endgame. What does that last turn look like when the deck you’re planning wins? Maybe your opponent is at three life and you’ve got a Mountain and a Lightning Bolt. Maybe your opponent is out of permanents and you’ve got seven cards in hand. Maybe you’re dead on board but have Ramirez DePietro and his merry band of pirate-ninjas on the battlefield, so you don’t really care (not everyone always plays to be the last man standing, right?). Maybe you’re trampling over with half a dozen green Spirits. Let’s go with that one.

On a fresh piece of paper, at the top write:

That’s all we know for now, but that’s fine because we know what our endgame looks like. Next we have to figure out how to get there, so let’s work backwards. Write:

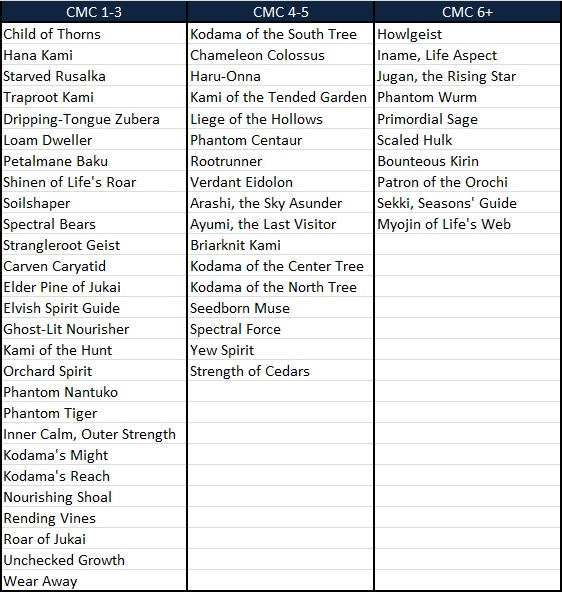

Simple enough. Gatherer time. There are 65 green Spirits and thirteen green Arcane spells. We’re going to have to play a lot of pretty awful cards to make this work, but we knew that when we dove in with a Kamigawa legend.

Well, that’s not all of them, but that’s still a bunch of weak cards. A few of them are surprisingly rad, though, and at least we have enough volume. This deck won’t be impossible. We probably want as many little Spirits as possible so that we can play a bunch of them at once and also to make sure we’ve got a decent army when we start filling the board. Loam Dweller, Petalmane Baku and Verdant Eidolon will all help get mana for that one big turn. Shinen of Life’s Roar might help us connect. We’ve also got some solid fat and a few more pretty decent Kamigawa spiritcraft triggers.

Now we’re playing all these creatures. How did we get there? Let’s take a step back and look at the turns immediately before the big win.

These are the main areas that any multiplayer aggro deck needs to commit to, especially mono-green. Without lots of focus here, our deck is just going to slowly make a few 2/2s with underwhelming abilities and then run out of steam. In our case, since we’re playing (or trying to play) so many creatures in a short time, the best way to keep trucking is to make sure that they’re replacing themselves. We’ve already got Primordial Sage, which is exactly what we need, so let’s push that theme as hard as we can. Glimpse of Nature, Recycle and especially Soul of the Harvest will keep us churning past the jank.

Cream of the Crop will be amazing when one of those is active, making sure to keep the gas flowing. Wild Pair gives us twice the army while we’re doing it. Genesis and Greater Good turn our creatures into cards in different ways, giving us value during the inevitable sweepers and regenerating an army for round 2 (and 3 and 4). If we’re sacrificing our guys anyway, we may as well profit further with Skullclamp and Fecundity! Regal Force would most likely be amazing, especially off of Myojin. Creeping Renaissance will be very useful for emergency refills.

Now let’s work on getting all the mana we need to make all these plays. Again, the theme of the deck is to play a bunch of guys, so let’s use that. Urza’s Incubator, Semblance Anvil, Emerald Medallion, and Cloud Key effectively generate mana every time you cast a creature, so they’ll work especially well when we’re casting a bunch of spells per turn. Earthcraft does it even better if we’re willing to tap our creatures (so far we have no reason not to). Depending on how many Arcane spells we end up with, Long-Forgotten Gohei could net some good savings, and it’ll always pump our team. Since on the Big Turn our new guys are probably summoning sick anyway, doubling down on Ashnod’s Altar, Food Chain, and Phyrexian Altar might be a good idea.

When we play a bunch of creatures to make our team huge, it’s a shame when they can’t join in. Concordant Crossroads and Akroma’s Memorial should go in automatically as the only mono-green sources of mass haste. Keldon Battlewagon is very janky but effectively gives your sick Spirits haste if it’s in play at the beginning of the big turn. That’s probably too win more even for this deck, though.

One more step back. We cast all those spells and attacked for all that damage, but if we didn’t have an army already in play, that flurry of action isn’t very relevant. A lot of our creatures in play will be random Spirits, of course, but we don’t want to empty our hand before South Tree is ready to help out, so let’s consider a token subtheme.

Not much to say here. Here are my favorite token generators, though we won’t have room for all of them: Awakening Zone; Ant Queen; Sprout Swarm; Deranged Hermit; Thelonite Hermit; Mycoloth; Mitotic Slime; Wolfbriar Elemental; Imperious Perfect; Howl of the Night Pack; Beacon of Creation; Kessig Cagebreakers; Garruk Wildspeaker; and Garruk, Primal Hunter. Fresh Meat and Caller of the Claw won’t proactively make an army, but they’ll do in the event of a reset. We’ll sort through them later.

That’s a solid skeleton, and we’ve got this deck’s storyboard completed for the last few turns. Let’s flesh this thing out. What else is this deck doing during the middle game? How did we get in the position where our opponents allowed us to cast all these spells? We’re shaping up to have a pretty strong subtheme of sacrificing creatures, and we should have lots of food for it. Let’s find some synergy for that.

Listed, we have Ashnod’s Altar, Food Chain, and Phyrexian Altar to turn dumb bodies into mana. To turn them into cards, we have Greater Good and can use Perilous Forays, Helm of Possession, Birthing Pod, and Momentous Fall for more. All very solid cards in their own right. If we want to go all-in, Blasting Station could work when we go into berserker mode, but I feel like that’s not quite worth it (though turning Beacon of Creation into the good half of Corrupt ain’t bad).

The other side of the coin is finding cards that give us extra benefits when our creatures die. We have Fecundity and Skullclamp in this category, which will be awesome, and we can throw Gutter Grime and Death’s Presence onto the pile without even thinking about it (but let’s think about it for a second anyway and imagine Death’s Presence and Greater Good on the battlefield at the same time—holy moly!).

We don’t really want to spend much mana during certain turns, but Foster makes sure our hand will be full with exactly what we need. Lightning Coils provides an instant army for South Tree to buff up, and Mimic Vat provides a steady stream of food for our outlets. Jar of Eyeballs is solid draw if we feel like we’re lacking. Finally, I dunno yet how saucy I’m feeling, but Lifeline can break a game completely in half if you’ve got a good sac outlet and an ETB ability or two.

Time to consider some other potential endgames, such as the ones in which we lose.

Every deck needs a back-up plan in case plan A fails for some reason, and in our case plan A is our commander. Let’s add a few cards that mimic South Tree’s effect so that our efforts don’t go to waste if it gets tucked or something and also something to protect the team from sweepers. I like Beastmaster Ascension, Eldrazi Monument, good ol’ Coat of Arms, and Triumph of the Hordes if you’re feeling the one-shot-kill. Kamahl, Fist of Krosa. Kamahl is especially good since in addition to Overrun and threatening opponents’ mana in retaliation to a sweeper he adds dudes for the big attack if you’ve got more mana than creatures. Synergy. On that note, maybe try Rude Awakening for the surprise factor late in the game.

Here’s also where you’d add more disruption, but since we’re the aggro deck, we don’t want to go overboard. If there is any that you see that also fits one of the above categories, though, it’s going in. Obviously, the Arcane removal spells are your first choice. Night Soil is a great card. Hornet Queen defends. Primal Command is a decent fit for any green deck. You’ll probably have enough tokens to use Nullmage Shepherd right, though I’ve always thought that she gets play in a lot of decks that really shouldn’t. Beast Within will always solve a problem and occasionally add that one last guy to put your alpha strike over the edge.

If we’ve got any holes left in our strategy, it’s finally time to plug them. Also any side synergies that might not directly fit your main game plan. Insert here: Eternal Witness; Yeva, Nature’s Herald; Cloudstone Curio; Wickerbough Elder; Mind’s Eye; Sensei’s Divining Top; Citanul Flute; Doubling Season / Dual Nature; Duplicant, etc. if they’re necessary. I tend to play as few of these as possible since it usually makes your deck less fun and often just makes it worse.

We’ve got well over a hundred cards here, so there are a few variations of the deck available out of just the cards above. Here’s my first draft of the deck. Lean, mean, and mono-green:

Creatures (33)

- 1 Kodama of the South Tree

- 1 Scaled Hulk

- 1 Petalmane Baku

- 1 Patron of the Orochi

- 1 Loam Dweller

- 1 Myojin of Life's Web

- 1 Jugan, the Rising Star

- 1 Liege of the Hollows

- 1 Soilshaper

- 1 Rootrunner

- 1 Kodama of the North Tree

- 1 Iname, Life Aspect

- 1 Hana Kami

- 1 Genesis

- 1 Phantom Centaur

- 1 Arashi, the Sky Asunder

- 1 Bounteous Kirin

- 1 Briarknit Kami

- 1 Elder Pine of Jukai

- 1 Sekki, Seasons' Guide

- 1 Shinen of Life's Roar

- 1 Carven Caryatid

- 1 Primordial Sage

- 1 Starved Rusalka

- 1 Verdant Eidolon

- 1 Spectral Force

- 1 Chameleon Colossus

- 1 Regal Force

- 1 Mycoloth

- 1 Kessig Cagebreakers

- 1 Strangleroot Geist

- 1 Soul of the Harvest

- 1 Yeva, Nature's Herald

Lands (38)

Spells (29)

- 1 Glimpse of Nature

- 1 Urza's Incubator

- 1 Emerald Medallion

- 1 Earthcraft

- 1 Food Chain

- 1 Fecundity

- 1 Wear Away

- 1 Kodama's Reach

- 1 Beacon of Creation

- 1 Ashnod's Altar

- 1 Skullclamp

- 1 Lightning Coils

- 1 Recycle

- 1 Helm of Possession

- 1 Foster

- 1 Greater Good

- 1 Rending Vines

- 1 Perilous Forays

- 1 Wild Pair

- 1 Akroma's Memorial

- 1 Cloud Key

- 1 Cream of the Crop

- 1 Eldrazi Monument

- 1 Awakening Zone

- 1 Fresh Meat

- 1 Birthing Pod

- 1 Creeping Renaissance

- 1 Gutter Grime

- 1 Death's Presence

Some people complain that you can’t build mono-green in any creative ways and every mono-green deck is the same. All you have to do, though, is start at the end!

*Solution to the chess problem (all chessboards courtesy of http://www.apronus.com/chess/wbeditor.php): Qg8+, Rxg8, Nf7#