What is it that separates Magic’s greatest players from the rest of us?

This is the kind of question that doesn’t have a right answer. You could

ask ten different great Magic players and get ten different answers, and

none of them would be wrong. Yes, the best players in the world are better

at combat math than the rest of us. They think more steps ahead; they play

a lot more Magic. They have access to teams and resources the rest of us

can only dream of; they make fewer mistakes. All these things are true, but

none of them are interesting.

For me, the interesting answer to this question isn’t a quality;

it’s an attitude. The best players in the world are devoted to obtaining

every possible edge in a game of Magic, no matter how small. Where the rest

of us shrug and decide it probably doesn’t matter very much, the best of

the best devote themselves to figuring out the right answer and

implementing it every time. There’s a lot of Magic waiting to be played on

the margins, Magic you could go your whole life without ever thinking about

while the world’s best lose sleep over it.

To head-off a possible line of discussion: no, I’m not talking about

cheating or angle-shooting. Some might define these things as edges to be

gained, but I wouldn’t, nor would any reputable Magic player. Believe it or

not, Magic is more than deep enough to continually reward your study of the

game with ethical edges, no matter how much time and effort you sink into

it.

I don’t have a how-to guide for you on these elusive edges. You’re not

going to read this article and magically understand all the razor thin

edges that the best players have over you. There’s no substitute for hard

work, and if there were, this article certainly isn’t it.

that every game has unique circumstances you can take advantage of if you

know how.

No, my goal is to open your eyes. It’s way too easy to get trapped in the

Magic you know and become unable to even imagine the rest of what the game

has to offer. It’s all too easy to spend all your time playing Magic

thinking about the same things you’ve always thought about, never anything

new. You’ll get better at the things you know about that way, but you’ll be

inherently limited as a player.

The good news is that all you need to do is be exposed to these minute

edges once and then set your brain churning on them. I can’t tell you how

to use these things to increase your win rate 5% in every format, but I can

show you that these things are out there. The rest is up to you.

Risk Versus Reward

I’m going to ease you in to start. Think back to all the times during a

match of Magic when you’ve seen a possible line and immediately recoiled.

“That’s way too complicated, and I have no idea if it’s right or not. I’m

just going to play it safe and take the line I know is alright.”

This is a common scenario for many of us. We reach a point in a game where

we think a certain play, maybe a potential attack or a way to sequence,

might be right, but we’re not sure and the play is weird. It

probably goes against common wisdom in the matchup, likely playing outside

of the role you’re meant to be. Despite all that, the play looks appealing

anyway, but you never make it.

This is a very classic risk versus reward scenario. You have a play on your

mind which, if it’s wrong, it’s wrong by a lot. Attacking when you

should have blocked is a mistake that’s hard to come back from. These

unorthodox plays are always very risky, but at the same time, don’t come

with a lot of reward. If they’re better than the orthodox play, it’s only

by a little. Often, they’ll leave you in a position to win on the margins,

but games of Magic don’t come down to the margins often enough for that to

be worth the risk when you’re not confident in the play in the first place.

The calculus here is simple: you don’t make the play. It’s not a difficult

decision in the end. Making the play involves taking on a lot of risk for

little reward, so making it is foolish. So, you don’t make the play and

move on with your life. Then the next time a spot like this comes up, you

don’t make the play a little quicker. You’ve already done that math. This

pattern repeats, until eventually you stop even really thinking about

unorthodox plays since you never make them. You’re stuck.

Example: You’re playing Jund against Humans. Your opponent has led with

Champion of the Parish into Kitesail Freebooter, and your only battlefield

presence is a 4/5 Tarmogoyf. You were on the play, and on your turn 3

you’re planning on playing a Scavenging Ooze and a tapped land. Do you

attack with the Tarmogoyf?

The orthodox answer here is a resounding no. Humans is firmly the aggressor

in the matchup and attacking with the Tarmogoyf is trading four points of

damage from the Goyf for likely three points of damage from the Champion,

not a good trade when your life total is the more relevant one. However, if

you broaden your thought range just a little:

Attacking with Tarmogoyf lets you get value out of it in the event that

their turn 3 play is Reflector Mage. You’d always rather have your cards do

something rather than nothing, and attacking this turn is a clear way to

guarantee your Tarmogoyf does something. Some games will come down to the

four damage mattering, but most won’t.

This is the exact kind of play I’ve been talking about. There’s a clear and

good reason for making the unorthodox play, but it’s still unorthodox. If

it’s right, it isn’t right by much. Making the play doesn’t make much

sense, until you consider the fact that finding the actually correct answer

in these spots is one of the things that makes the great players great. If

the play is right, making it this time won’t help you much. But making it

every time, it’s right over the course of your career? Now we’re talking.

I don’t know the right answer for this example. I mean, I couldn’t possibly

have one because it depends way too much on context. The play is right on

the line. But the correct answer to this Jund example doesn’t matter very

much. What matters is the idea that if you want to be the best, you can’t

shortcut these things to “probably not worth it” and forget about them. You

need to resolve yourself to stop shrugging and start actually answering

these questions. This will probably mean experimenting with some wild lines

in-game, and that will probably translate to some losses along the way, but

no one ever said the path to greatness was easy.

Playing the Forcing Game

Some of the coolest plays you can make in Magic involve dabbling in the

forced-play space. You know that your opponent is forced to make a specific

play and there’s lots of ways you can punish them. Let’s look at an

example:

You’re playing Burn against an opponent who, surprise surprise, is playing

Jund. You skillfully won the die roll and lead on Goblin Guide. The trigger

reveals a Lightning Bolt. After drawing said Lightning Bolt, your opponent

plays a Blackcleave Cliffs and passes the turn. Do you attack?

One of the keys to the Jund versus Burn matchup is that Burn’s creatures

are mostly awful. Jund plays a lot of removal and can generally ensure that

all of Burn’s creatures are good for one attack at most. That’s good,

because Jund stands no chance when Burn gets to use its creatures as

recurring damage sources.

Here, you know your opponent has the Lightning Bolt for your Goblin Guide.

If you attack, they’ll resolve the Goblin Guide trigger and then Lightning

Bolt your Guide before damage is dealt. This play is virtually forced from

them, they can’t afford to take extra damage from your Goblin Guide. But

what if you don’t attack, and instead just play a land and pass the turn,

Boros Charm at the ready?

Most of the time, your Jund opponent will grimace and Bolt your Goblin

Guide at the end step. They have plenty of removal and can’t afford to take

any more damage from that Guide, so they may as well be mana efficient.

When this happens, you have won the exchange: you denied them a Goblin

Guide trigger. A small edge, but an edge nonetheless.

But will this always be the case? What if the Jund player happened to be

very short on removal and is so scared of Eidolon of the Great Revel that

they feel they must hold the Bolt for it? What if it’s post-sideboard and

they have a Collective Brutality they really wanted a target for? Most of

the time, they will Bolt the Guide, but not always. Whenever they don’t,

you’re behind on the exchange and would have been much better off by truly

forcing their hand with the attack.

The moral of this story is that there’s room to find edges in subverting

your opponent’s expectations when they have a forced play, but you must be

careful. In general, all these plays will be in the genre of making the

play your opponent is forced into less good, but you must make sure you

don’t make it so much less good that it’s no longer forced.

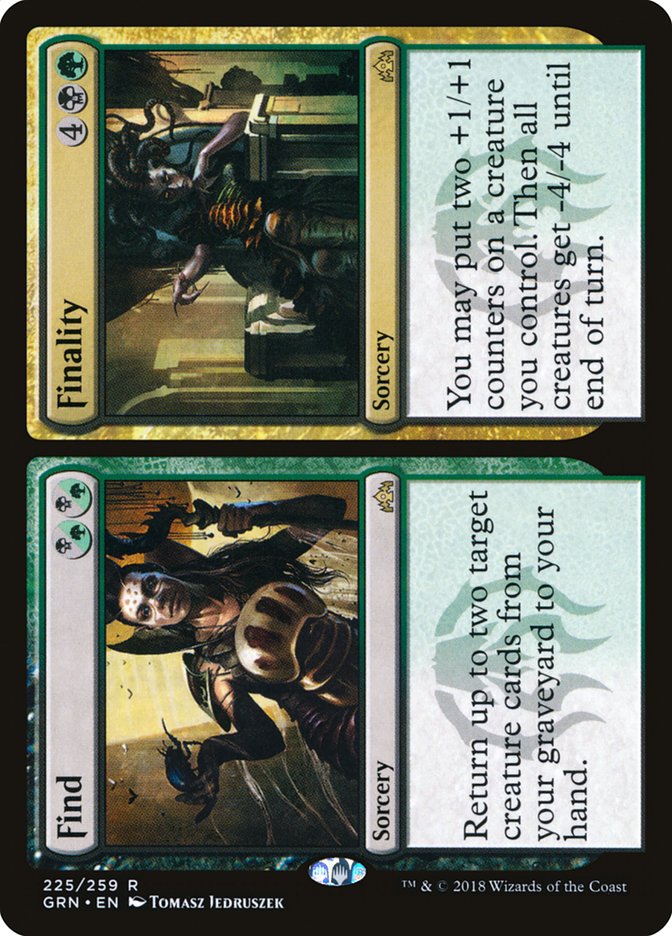

Real Example: Late in a Standard Golgari Midrange mirror, I’m way behind.

My opponent has a terrifyingly wide battlefield protecting a Vivien Reid

that I haven’t matched. My only asset is a Carnage Tyrant and some

Wildgrowth Walkers, but I’m so behind on the battlefield that they can’t

attack. I’ll be losing to Vivien Reid’s ultimate in short order unless I

find a Finality.

I play a Jadelight Ranger to dig and see the Finality finally. I pass the

turn, and my opponent knows what’s up. On my next turn, I will play

Finality, clear their battlefield, and get some chip damage in on Vivien

Reid. This play is forced by me and it’s now their job to weaken it. They

choose to employ the time-tested strategy of attacking when your

battlefield is about to be wrathed, but things go awry: they attack too

much. They swing so heavily into my defensive Carnage Tyrant and assorted

small creatures that on my next turn, I’m no longer forced to cast

Finality. I instead cast Find, develop my battlefield, attack the Vivien

and suddenly find myself ahead in a game I don’t think the Finality would

have won for me.

Ultimately, these scenarios are yet another example of the risk versus

reward problem from before; when your opponent is forced to make a specific

play, it means times are tough for them. You can make use of the fact that

you know what they must do to gain a small edge, but if you go too far you

risk throwing the game away. Often, this means that we just don’t punish

our opponent’s forced plays because we’re scared of the things that can go

wrong. Once again, this is a great strategy for being mediocre at Magic,

but not a good one for being great. Learn, test your limits, and explore

how these scenarios work. Accept that you’ll lose along the way, but the

losses won’t be forever.

One last note before moving on: the Jund versus Humans example from the

last section actually has a really neat forced play element to it. If you

choose not to attack with the Tarmogoyf and your opponent has a Reflector

Mage, they are very likely to play it. If you attack and they have both

Reflector Mage and Mantis Rider, they are now heavily incentivized to just

jam the Mantis Rider. This dynamic makes the attack worse, but not so much

worse that I think it’s always wrong. Always keep in mind that changing

your play will cause your opponent to change theirs.

Unique Circumstances within Pattern Recognition

When describing Magic to the unenlightened, one of the go-to phrases is

something along the lines of “it’s a cross between poker and chess.” Fair

enough. It’s the chess part I want to focus on right now.

One of the big differences between Magic and chess is that in chess, the

capabilities of the pieces are well-defined and narrow. On any given turn,

you know which eight squares your Knight can move to. On an empty board,

your Bishop might be able to move to any of thirteen squares. You can tell

these things at a glance and know exactly what your pieces are capable of.

Magic isn’t so simple.

One of the biggest hurdles to becoming a mediocre Magic player is

understanding that the abilities of your cards are limited. Hand a

relatively new player a Humans deck and the range of things they will

consider naming with Meddling Mage will be roughly as large as their

imagination. The number of attacks they decline with Kitesail Freebooter

because “they might need to block” will somehow be higher than that range

is wide. Magic cards can do a lot of things.

The first big level up in Magic is understanding that despite the huge

range of things your cards can do, there’s a much narrower range

of things they should do. Your aggressive creatures should attack,

your Meddling Mages should name one of four cards in your opponent’s deck.

These things are much more scripted than they appear at first blush.

Understanding a matchup in Magic is all about pattern recognition. If you

go into a new matchup cold, there’s probably a lot of things you think you

can do to win. Most of them are wrong. Magic rewards staying in your lane

pretty heavily, and most matchups will punish you for straying from that

lane. Your cards all have a job to do and it’s your job to make sure they

do their assigned work.

The second big level-up in Magic is understanding that despite the narrow

range of things your cards should do, there’s a huge range of

things they can do.

The most powerful moments in tournament Magic come about when someone uses

a card to do something that it doesn’t normally get to do. See: the

following Pro Tour Quarterfinals match.

I highly recommend watching the video. It’s even already at the right time

stamp so you don’t have to do any work. In short, the play involves using

the -1/-1 mode on Golgari Charm to counter the exile target creature with

power 5 or greater mode on Selesnya Charm. The play is much more intricate

and much cooler than any short description could do justice to, but that’s

the short version.

Countering Selesnya Charm isn’t why Ichikawa put Golgari Charm in his deck;

that’s not what it’s there for. This use was extremely fringe and extremely

good. It’s exactly the kind of play that separates the best from the rest.

Anyone can understand this play once it’s pointed out to them, only the

best can create it from thin air when needed.

It’s really hard to see plays like these when so much of the rest of Magic

trains us to ignore them. Magic is too complicated and has too many moving

parts to be able to fully consider every possible line. We’re rewarded for

first understanding what cards are meant to do in matchups, and then

disregarding every other possible use. This is fine and a great first step,

but to push past merely good you have to a step further and strive to

broaden your range once again.

In the end, what all this comes down to is the idea that being good at

Magic is an exercise in figuring out what the elements are that matter in

90% of games and ignoring everything else. Being great at Magic is all

about mastering the 90%, and then bringing the rest of Magic back into

focus and mastering the niche plays that will get you through the other

10%.

For all that we consider matchups to be formulaic and for the deck involved

to have well-defined roles, that’s not really the truth of the matter.

Every Magic game is unique, and that means that every game has unique

circumstances you can take advantage of if you know how. You have to do so

within the rules of engagement of the matchup, but there are always ways to

profitably do so if your knowledge base is broad and your imagination is

ready.

Just make sure not to lose yourself so completely in that 10% that you

forget about the 90% you mastered.