From the moment I first laid eyes on of the new Saga cards in Dominaria, I knew I was in love. Not with the new frame they’re

getting, although I do like the look a lot. Nor am I simply an enchantment

fan girl; indeed, I’ve never registered an Eidolon of Blossoms in my life.

Honestly, it isn’t anything intrinsic to the Sagas themselves that draws me

in, it’s the challenge they represent that intrigues me.

I wasn’t playing Magic when Lorwyn released. I didn’t get to

participate in the quest to understand Planeswalkers. There’s a lot of

reasons why I wish I had started playing Magic sooner, but that’s one of

the big ones. Sagas are no Planeswalkers, but they are a new

subtype chock full of new play patterns to dissect. For my money, they’re

the weirdest addition to Magic since the printing of the first five

Planeswalkers, and I am hyper excited for the opportunity to figure out

what makes them tick.

I’ve been writing Magic articles for nearly three years now, here at

Starcitygames.com for nearly half of that, and yet in many ways I’m still

getting used to it. I spent way too much time eagerly awaiting a Saga

article so that I could compare notes with my evaluations. And then it hit

me: wait, am I supposed to write a Saga article?

Well, let’s see. Brand new subtype? Check. New mechanic that scripts play

patterns? Check. The need to factor multiple turns of potential counter

play into any analysis? Check. Well, when you put it like that, it does

sound an awful lot like my wheelhouse, doesn’t it?

And so, write it I will.

But before we begin, let’s talk a quick second to talk about what we’re

trying to achieve here. My goal is to provide the tools to evaluate Sagas

with. I’m not going to be shipping sweet Dominaria Standard Saga

decks, nor will I stack rank all the Sagas in Dominaria. To be

frank, those things require a lot more data than I currently have, and I

want this piece to be relevant going forward. I want you to be able to use

the information here to evaluate Sagas now, and then to be able to use it

again to reevaluate them as we start to figure out the general shape of Dominaria Standard.

The Planeswalker Comparison

Let’s take a look at a Saga:

The new Saga frame certainly looks different from anything we’ve seen

before, but the card itself is easy enough to understand, even if it is

difficult to evaluate. Time of Ice enters the battlefield and freezes an

opposing creature, and then does the same thing the turn after that. On its

last turn on the battlefield it returns all tapped creatures to their

owners’ hands. Individually, these chapter abilities aren’t hard to

understand. What makes Sagas interesting is the time delay they attach to

these effects, something that is remarkably dissimilar to nearly everything

else in Magic. We need something to compare them to.

One of the earliest takes I saw out in the wild after Sagas were first

previewed was the idea that they are like mini-Planeswalkers in a lot of

ways and should be evaluated as such. This idea has now been repeated a few

times and is currently our best lens for examining the Sagas. Now, I have a

lot of problems with the comparison, but it is a very good

starting place. The best way to understand new things in Magic is to find

the element of the game that is as similar as possible, and then zoom in on

the differences.

The similarities between Sagas and Planeswalkers are pretty easy to spot.

They are both hard to interact with permanents that provide a variable

single effect each turn. Despite lasting theoretically forever, we’re used

to Planeswalkers playing out in a very Saga-like manner because

Planeswalker battles play out the same way time after time. The terms of

engagement are clear.

Let’s look at the best Planeswalker in Standard right now: Chandra, Torch

of Defiance. Whether she’s coming at us out of the Grixis Energy deck or

the sideboard of the Mono-Red Aggro deck, we know exactly what to expect

from Chandra. There’s two kinds of Chandra fights, it turns out. The good

fights, where she’s forced to come down and immediately minus three a

creature, putting her very low on loyalty, sure to die in the next couple

of turns. And then there’s the bad fights, where she gets to use one of her

plus abilities right off the bat and continue to use them until you manage

to put her under enough pressure to force the minus three before she dies.

Chandra has four abilities printed on her, three of which can be used on

most turns. And yet, the turns after she comes down are fairly scripted.

This is why the comparison between Planeswalkers and Sagas works at all,

and where it comes from. Sagas aren’t that similar to Planeswalkers in the

abstract, with their potentially infinite lifespan and multiple options

every turn, but they are similar to Planeswalkers in practice,

where both players know how the next few turns are going to play out the

second a Planeswalker hits the battlefield.

So then, here’s the first difference we need to keep in mind: you can’t win

a Saga battle. Obvious, but important to specifically call out before we

start comparing Sagas too heavily to Planeswalkers. A Saga can’t win you

the game by sticking around uncontested, a Planeswalker can. This potential

of Planeswalkers, despite its rarity, contributes significantly to their

overall value.

On the other hand, you also can’t lose a Saga battle. Sometimes

when you’re behind in a game, your Planeswalker just isn’t going to be very

effective. It’s going to come down, do something minor, and then die an

ignoble death. A Saga doesn’t very much care if the game isn’t going your

way. Enchantment removal spells aside, Sagas are going to do the same thing

for you every time.

Where does this leave Sagas, in comparison to Planeswalkers? On balance, weaker. Being able to run away with the game is a huge

perk of Planeswalkers, one that is in no way mirrored in Sagas. Still

performing in games that have gotten away from you is nice, but not nearly

as impactful as the ability to steal games that you’re ahead in.

The Generalized Punisher Problem

There’s one other major departure from Planeswalkers that I want to

discuss, but first we need to backup and talk about yet another Magic

mechanic.

The inherent weakness of cards with the punisher mechanic remains to this

day one of the most interesting things I’ve ever learned about Magic. In

brief, punisher cards are cards that, like Vexing Devil, give your opponent

a choice between two bad-for-them options. In the case of Vexing Devil,

your opponent gets to choose whether you just cast a better Lava Spike or a

better Wild Nacatl. Lava Spike and Wild Nacatl are both fine cards, so a

card that’s always strictly better than one of them must be good, right?

As many of you already know, the answer to this is a resounding no.

Somehow, punisher cards are always much weaker than the sum of their parts.

Well, I shouldn’t say “somehow.” That makes it sounds like this fact is

some kind of bewildering phenomenon, when it’s actually pretty easy to

understand. The thing is, your opponent in a game of Magic is a living,

breathing, thinking human. Fun factoid about living, breathing, thinking

humans: they are quite good at choosing the option that is best for them.

When a 4/3 isn’t as much of a problem as taking four to the face they give

you a 4/3, and when they’d rather just lose four life, they go ahead and do

that. This isn’t new territory, and I won’t spend any more time rehashing

the ground. Trust me, it’s important for what comes next.

The core of the punisher problem is that your opponent is as capable of

coming up with and executing plans as you are. This is a problem for the

Saga subtype. Planeswalker fights may be scripted, but they can go

off script. When things are looking bad for your Plant tokens, Nissa, Voice

of Zendikar can just start -2ing, even though that isn’t the typical play

pattern. There is no potential for Sagas to do anything other than what

they say they’re going to do, and that gives your opponent a lot of

opportunity to prepare.

In terms of what they do, the Sagas are all over the place. One of the few

commonalities is that, for the most part, their coolest, splashiest, and

most powerful effect comes at the very end of their time on the

battlefield. In other words, the most powerful thing most Sagas do is the

thing your opponent has the most time to prepare for.

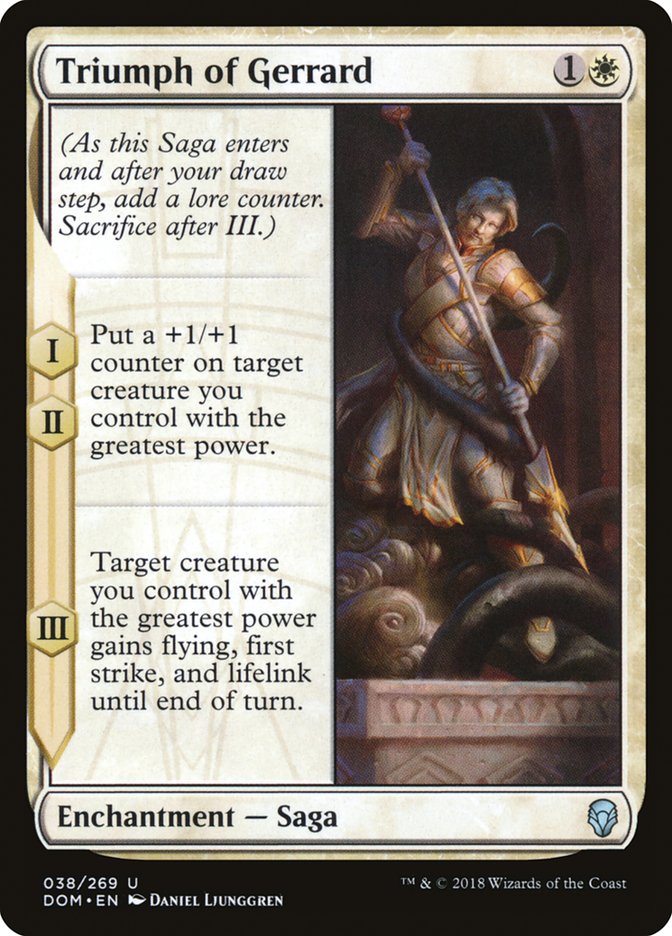

We know how to evaluate “Target creature you control with the greatest

power gains flying, first trike, and lifelink until end of turn.” It’s a

powerful effect that swings races in our favor and lets us swoop in for the

last few points of damage. But how do we evaluate setting that effect up to

take place two turns from now?

Spoiler: it’s worse. Much worse. If your opponent knows this is coming,

they can do all sorts of things to stop it. From saving a removal spell to

ensuring they have a flying blocker, they have lots of ways to make sure

this effect is not everything that you want it to be.

Yes, you get the same chance to set-up for the effect that your opponent

gets to set-up against it. In general, your opponent’s ability to reduce

the power of the effect will be greater than your ability to increase it.

The reason for this is timing and specificity. You’re setting up to do a

very specific thing at a very specific time, and your opponent can stop you

by doing any number of things over the next couple of turns.

They can kill every creature you have or save a removal spell for the

trigger. They can turn the game into a race, and then plan to block with a

creature of their own they can kill so they can deny you the lifelink. They

can thwart your plan in any number of ways, but you can only execute it in

one.

Now, you might be thinking to yourself that this is no different than any

other Magic card. When you play a Search for Azcanta, your opponent can

start planning for and playing to beat Azcanta, the Sunken Ruin. If they

won’t be able to beat you in a drawn-out affair, they can channel all their

resources into ending the game before you can take advantage of your

Azcanta. How are Sagas different?

The main difference is that Sagas do a single thing at a discrete point in

time. Search for Azcanta sets up a subgame of transforming, and then starts

to look for extra resources every turn. It’s much harder to stop a chronic

play pattern than it is an acute one. Your opponent can devote tons of

resources to a single turn to take away all the advantage from your Saga,

but there is no such timing window they can use to nullify your Azcanta,

the Sunken Ruin.

The more all-in you are on your Saga, the harder it is for your opponent to

stop.

If the only Knights in your deck are the tokens that History of Benalia

produces, setting up to weaken its third chapter ability is trivial. All

they must do is kill two Knight tokens and the third chapter won’t do

anything at all, or they can sit back with a couple five toughness

creatures and plan to block on that Inspired Charge turn.

If every creature in your deck is a Knight, the main way for them to

nullify the last ability on your History is to be beating you on every

relevant axis already. There’s still some things they can do, like time

their Fumigates to the turn before the third chapter ability goes off so

that you are forced to rebuild with summoning sick creatures on the

relevant turn, but for the most part, their options are limited.

So, the takeaways: Sagas are weaker than you think they are at first read,

largely because your opponent can and will plan to weaken the later chapter

abilities. If one intrigues you, go as all-in on it as you can to take away

your opponent’s potential for counter play. For this reason, The Mirari

Conjecture is one of the most exciting Sagas to me, because its third

chapter ability has very limited counter play. Similarly, Phyrexian

Scriptures is exciting because its most powerful ability is the second

chapter ability, not the third.

By and large, many Sagas will be carried by the first chapter ability. It’s

the ability your opponent can’t set up to weaken, that gives you immediate

return for the mana you spent on the Saga. It’s hard for me to imagine The

Flame of Keld seeing much play for no other reason than it doesn’t even

begin to pay you off until the next turn. By contrast, History of Benalia

is exciting despite its third chapter ability being easy to maneuver around

because the first ones are good value. Ditto for Fall of the Thran.

Abuse and Risk Cases

The last thing I want to look at is the unique risk and abuse cases that

apply to Sagas. First, the primary risk case: they are weak to enchantment

removal.

How important this is largely depends on how good enchantments are in the

format, which includes the Sagas themselves. If Sagas are everywhere, you

can probably expect to see enchantment removal running about. That’s okay

though, because the threat of removal just doubles down on the pressure

already on Sagas: the first trigger is the most important. The very first

ability on a Saga needs to be something you’re interested in, both because

your opponent will be able to counteract its later abilities and because it

might not even get to live to see them.

The ways we can gain advantage with our Sagas is past what’s printed on the

card. The two most direct ways to do this are to return them to our hand

before they die and to place counters on them in some way separate from

their own effect.

Both of these kinds of abuse have the effect of compressing Sagas down to

fewer turns. This is good for evaluation, as the tricky thing about

evaluating Sagas is their duration. If an individual Saga is worth this

level of attention, the deck that does this is going to play out in very

un-Saga like ways. In a lot of ways, these methods are about turning Sagas

into ‘normal’ Magic cards, and as such, are not very relevant to evaluating

Sagas as a whole.

No, the interesting abuse case in my mind is a much more commonplace one:

playing multiple copies. It’s kind of a given that when a Magic card is

good, we’re going to play more than one copy of it. Indeed, most of the

time we’ll go ahead and play four. This is very good for Sagas.

The big weakness of Sagas is opponents playing around the discrete point in

time that they generate a big effect. If you play turn 3 History of Benalia

into turn 4 History of Benalia, you’re setting up two discrete

points in time your opponent needs to be ready for. That is far more than

twice as hard to do.

Further, because most Sagas have chapter abilities that synergize with each

other, Sagas self-synergize with additional copies of themselves. Drawing

two copies of Triumph of Gerrard is often more than twice as good as

drawing one copy. This isn’t true for every Saga, case in point Fall of the

Thran, but it is true more often than it’s not. If you want to play with

Sagas, you’d do well to play with as many as you can get your hands on.