Real-world flavor text is dead. So sayeth the Rosewater:

“We have so little space to tell our stories and show off our worlds that we’ve decided to use it all.”

It’s been almost two months since I first read that on Mark Rosewater’s blog. That’s time enough for me to process it and come to terms with the idea that

one of the beautiful qualities that drew me into Magic, the well-placed quote from world literature, will not be part of the game’s future.

I’m hooked now, of course, and will be for some time. But Magic’s not the same for me anymore.

Suddenly I want an emo group to cover a bunch of weepy country songs…

Skeeter Davis

and her maudlin tune aside, reading Mark Rosewater’s take on things at least gave me some closure, so I can look back fondly on the “real world” era of

Magic. Calling it a single era, though, is a little misleading, as there were several distinct steps in what was really a long goodbye. Let’s hop through a

portal to another time…

Me, bitter? Where would you get that idea?

In the Beginning: The Familiar and the Personal

The earliest printings of Magic, now known as Alpha, Beta, and Unlimited, had no established market to tap into or long-running

mythology. The initial set also had no overarching storyline (though it did contain the story of Worzel in the rulebook, for Alpha at least)

and minimal central oversight of the art. This led to several quirks:

A Mesoamerican-style pyramid on Ancestral Recall.

The Ankh of Mishra, the “ankh” being a real-world hieroglyphic imbued with mysticism in the 20th century.

Narratives in the third person and first, as on Benalish Hero (information told by a third-party narrator) and Black Knight (the Black Knight himself

speaks).

Medieval-ish dudes with crosses on their chests on the card Crusade.

Demonic Hordes, which literally has “Summon Demons” written on the type line, giving thousands of parents and preachers and parasites all the wrong ideas.

Dragon Whelp and its shoehorned-in flavor text, from a Marianne Moore poem (that was written in 1957 and still very much under copyright, whoops).

…and that’s just through the letter D! Early Magic had enough naive weirdness to make Brand and Legal join forces to pitch a royal hissy fit.

The first expansion set, Arabian Nights, drew its direct inspiration, and indeed its title, from the Southwest Asian classicOne Thousand and One Nights. A further inspiration for Dr. Richard Garfield was the recent

publication of “Ramadan,” an issue of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman.

Nobody’s ever mentioned the Disney film in connection with the set, but clearly it

was part of the zeitgeist, having come out the year before, in 1992.

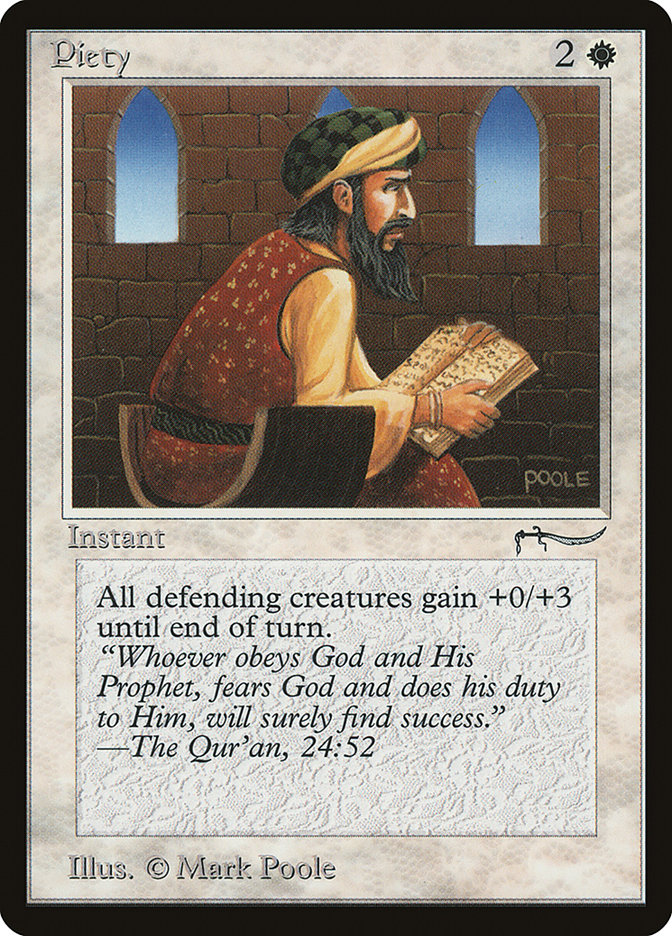

Arabian Nights

quoted liberally from several related sources in its flavor text, including two separate translations of One Thousand and One Nights, the Junior

Classics and Haddaway versions. It also quotes the Quran, sacred text of Islam, in English translation on

cards such as Piety.

But no set would rely so heavily on a real-world source as Arabian Nights did until the printing of Portal Three Kingdoms several years

later. The set Ice Age and its follow-up Alliances, forerunners of the modern set concept, took place in a frozen world clearly inspired

by Norse myth, but there’s no sign of Odin or Loki or Freya. Meanwhile, Antiquities elaborated on the stories of Urza and Mishra, sowing the seeds

for the storyline-dominated years of Magic.

And even Arabian Nights got the retcon treatment years later; officially, it takes place on the plane of Rabiah, not Earth.

The Silver Age: The Weatherlight Saga and Portal Three Kingdoms

After the early sets such as Arabian Nights and Legends, the game fell away from using real-world flavor text outside the core sets.

Instead it adopted a pattern of telling story points big and small on its cards, from climactic battles to…this.

After a pun like that, it’s mere justice that Squee outlived her.

The core sets and the beginner-level Starter and Portal sets continued to print real-world flavor text during this time, but one set

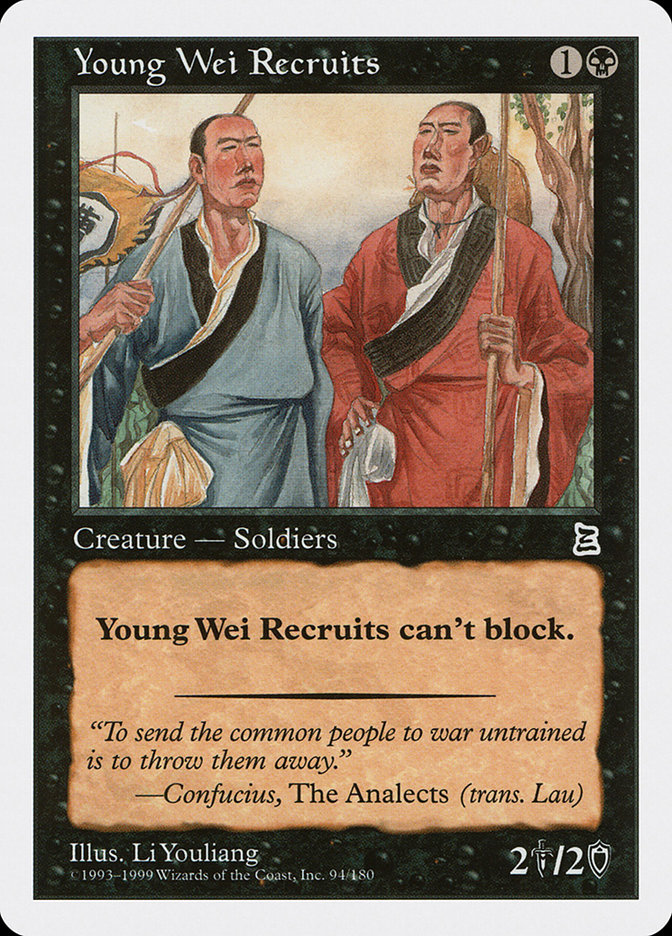

deserves special mention: Portal Three Kingdoms. Crafted especially for the Asia-Pacific market, it used the famous Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms as its source material and even included a

summary booklet of the story with preconstructed decks.

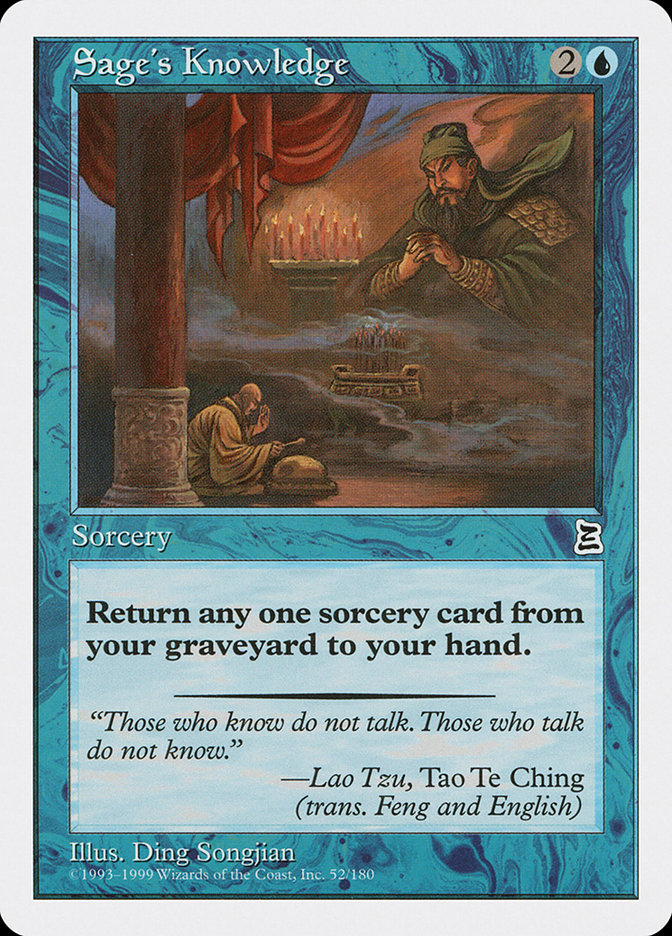

Naturally enough for a set themed around a classic of Chinese literature, the flavor text quotes liberally from the book — liberally enough that,

as I wrote a few years back

, its author outdoes even Shakespeare as Magic’s most quoted real-world writer. Portal Three Kingdoms also references the writings of several

religions and their philosophers, particularly Taoism and Confucianism, and the legendary general Sun Tzu.

While I can’t link to the

Epic Rap Battles of History

video itself… Lao Tzu, Sun Tzu, and Confucius.

Portal Three Kingdoms

had a specific goal of cracking the Chinese market — and the rigid codes that could have condemned the game as a frivolous diversion. Instead, Chinese

product got this glowing review:

“An intellectual sport approved for launch and promotion as a demonstration program by the Sports-For-All Administration Center of the State Sport

General Administration of China.”

And when the Chinese won the Team World Championship more than a decade later, it was kind of a big deal.

The Bronze Age: Weakening Bonds

After the changeover in card frames between Scourge and 8th Edition, a mini-renaissance of real-world flavor text came to the core sets.

For me, 9th Edition is particularly memorable for the political bent it took, especially in blue and black; the former color quotes“Mother” Jones on Archivist andEmma Goldman on Treasure Trove, while the latter color placed a Wilfred Owen poem on Cruel Edict.

After 9th Edition, though, the representation of real-world flavor text dwindled. Hand in hand with that change, there was a push to “de-Earthify”

the yearly core sets; among other changes, the classic Grizzly Bears were kicked to the curb and replaced with Runeclaw Bear.

The difference a year makes.

Magic 2013

was the first-ever core set not to have any real-world flavor text at all, an omission that did not go unnoticed. Magic 2014

brought back a couple of real-world quotes, finishing off a Sun Tzu “color” cycle in the process with Zephyr Charge, and

suggesting sunnier days ahead.

It was not to be.

Not for lack of trying, mind you, but the Magic 2015 Core Set had no real-world flavor text at all.

No Frederick Douglass, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never has and it never

will.”

No Tecumseh, “Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth?”

No Harriet Tubman, “I can’t die but once.”

No George Eliot, “Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them.”

And then there was Magic Origins, with ten planes of story to cover and no room for real-world flavor text. And now the core sets are gone, and

the chances of real-world flavor text with them.

The Current Age

So where does that leave fans of real-world flavor text? Looking back at the past, pretty much. There’s a slim chance we’ll see real-world flavor text pop

up in supplementary sets such as Commander, Conspiracy, or Planechase, but I’m not holding my breath.

Instead I’ll slip into cold comfort mode and have a bit of a chuckle. Despite the best efforts of Wizards to remove real-world references from the game,

they’ll never succeed entirely. Sure, they may lean on tropes more than specific source

material these days, but sometimes those tropes are a lot closer to the source material than others. Think Innistrad, which folded horror tropes

into a recognizably Magic world, and Theros, which seems more like Greek myth with the proverbial serial numbers filed off.

I also take comfort in the idea of the pendulum and how Magic swings between opposites. Once the game spent several years on a single all-saturating story

with not-terribly-compelling characters taking up all the oxygen. I’m sure Wizards has its story plans mapped out for a while, but I don’t see this new

storytelling mode as sustainable. In other words, this too shall pass.

Like a kidney stone.