[This interview with Dr. Richard Garfield, creator of Magic, originally was run in two parts on SCG Premium.]

The rise of digital media has enabled the production of games an order of magnitude more engrossing than the analogue games that came before. With the intensification of games, there’s grown a corresponding awareness of certain characteristics of games – namely, the efficient delivery of streams of solvable problems, and the accompanying surges of achievement – as psychological triggers useful for commanding attention. Gamification is the concept, typically associated with marketing, of either attaching these basic features to a product in order to stimulate consumer engagement, or, if the product’s already a game, amplifying these existing features in order to make it that much more compelling.

Magic has a unique position within this development. On the one hand, it’s as much an analogue game as Chess – it was designed to be played with physical pieces in a way that’s comfortable within physical space. On the other, Magic‘s innovation of making the game pieces tradeable commodities, thereby giving players tokens for preparing and customizing their strategy remotely, has the revolutionary effect of allowing the game experience to continue beyond the table. Previously, this degree of imaginative immersion was reserved for experts and eccentrics, not the ordinary person. In offering this level of immersion, Magic is a prototype for digital games with their unprecedented power for simulating game worlds and intensifying gaming experiences.

In considering this new landscape and Magic‘s place within in, I recently had the opportunity to consult the source. Richard Garfield, Magic‘s creator, is a game designer of the highest order. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of games, and there’s no doubt that his project is just to make outstanding ones, with profit being an important byproduct and potentially useful metric but not the goal. In this interview, we had the chance to talk about games in general, the issue of gamification, and some of the decisions that went into guiding Magic where it is today.

Jeff Cunningham (JC): So the patent for Trading Card Games is in your name. You opened the whole genre of gaming that’s exploded from that.

Richard Garfield (RG): Yes.

JC: You’ve listed numerous inspirations, like marbles, Strat-O-Matic Baseball, Cosmic Encounter, Dungeons & Dragons, Titan, and collectible cards, but it seems like the distinctive innovation – what you’ve sometimes described as the “aha moment” – is the idea of having discrete pieces, commodities that can be purchased and exchanged among the player base.

RG: Yeah, I think the “aha” for me was the realization that not all the players need to have the same game components. That was a big breakthrough in my thinking because until then I viewed games as being something contained, with everybody playing the same game. And a lot of these games that you mentioned, like Cosmic Encounter, or Dungeons & Dragons, were pushing up against the boundaries of that, where there’s so much variation in what you had, that in practice nobody played the same game twice. The further step was to actually have it be so that they didn’t even have the same game components, so there wasn’t even a chance of playing the same game twice.

JC: It sounds like you’re saying that because of those influences, the time was ripe for the innovation, and it’s latent in those forerunners.

RG: Yes. I don’t know what was in the air back then, and whether it was just random happenstance for me, or whether there’s a bunch of people who would have ended up there shortly or not. I do have confidence that something would’ve happened in the digital age because this idea of people not having the same game is much, much easier to do electronically than it is do with physical games.

JC: Magic seems unique in that way, as an analogue game released at the cusp of the digital era.

RG: Right. So technically, Magic could’ve probably existed, say, in the early 70’s. What would’ve happened, it’s really hard to say… because the internet was really powerful in getting it going. I could almost imagine that if it came out in the 70’s it would’ve worked but only if you had a huge campaign to get it everywhere at the same time, but it couldn’t have grassrooted like it did. So for example, you get a small town and a few people start playing, and one of them hooks into discussion groups and is sort of excited to be part of this world and see what’s going on there, and bridges that back. But the supply was so inconsistent back then, we didn’t have the capability of making too many cards. People might not have a supply or might be the only person in their area with one. These things will kill a game. You need a community.

JC: Right. So you couldn’t imagine it happening in the, say, 30’s or 40’s, with modified chess pieces or something like that.

RG: Certainly, technically, it could’ve been. There’s some technical challenges in shuffling a bunch of pieces or shuffling a bunch of cards. How vital is the tool? My guess is that the internet wasn’t required, but you’d have had to have an incredible investment to get it going.

JC: You’ve talked about your interest in the history of games, and the importance of the history of games, going back even to ancient games. How do you contextualize Magic in that history?

RG: I’m not sure how to answer that. Games are often evergreen – they’re good forever. Games from the Roman times – many of them have survived in one form or another until today, for instance, backgammon (or variations of it) was played back then and it’s still playable and quite a good game today. So, on one hand, I think there was a clear innovation that went on with Magic… aspects were there before, but it did something new. And, at the same time, I think it’s proven to be… or to potentially have… that evergreen quality where, depending on how people take care of it, it could be around forever.

JC: Turning back to the idea of establishing a classic game. What distinguishes games for you as an art form?

RG: Games are a really interesting medium. It’s certainly one that I feel like I’ve devoted my life to – I just love it – it’s such a great area for my view of the world. It’s this interface between imagination and mathematics. I’m mathematically bent – not “bent” as in weird, although that’s true too – but as in I lean toward mathematics. I have a math PhD, as you probably know; I really like math and puzzles, and people ask me how that influences my game design. The way it relates is subtle. The art in math is in some ways similar to the art in games, but games have more flavor added to them.

People don’t think of mathematics as an art, but a mathematician views certain things as beautiful, and certain things as less beautiful, and the questions they come up with, and the way they go about approaching them – I view as an art in many ways. For one, both are not as a rule applicable to anything – for example, if you’re an expert in 17th-dimensional Newtonian spaces, and that doesn’t happen to have an application, and you’re just doing it because other mathematicians appreciate it. Games are a lot broader than that, but I love that mix of logic and intuition.

And another thing I’ll say about games is that they’re more like music than they are like books. There’s a lot of art which is something that you see and understand and then the value of it has been exhausted. You read a book, you’ve taken it in, and you can read it again, and it might have meaning again, but it’s very significantly changed. Games, you play again and again and they get better and better over time as you understand them better. That’s one of the reasons why people play a single game over their lifetime: it’s because the more they’ve invested, the better that game is for them. And that’s closer to music, I think – where the more you hear the piece, the more you understand it, and integrate it into your brain.

Music also has that relationship to mathematics – there’s logic and math there, but there’s also something on top of that, which is that interface I like so much with games. I’m not a musician but I’ve tinkered with a piano, and I’ve tried to teach myself, and there’s something really magical that happens to me – it works really well for my way of thinking – where parts of my brain that I don’t know exist are responding to something. It’s like not understanding something – I think about it, I can see some logic, but it’s right on that edge of intelligibility, and it’s really very tantalizing, in a way that’s similar, I find, to games.

JC: So there’s a mechanical substrate with a design interface. And that mechanical substrate has to be a compelling problem to be interesting; it can’t just be a shallow one.

RG: Right.

JC: The surrounding landscape has changed since Magic was created. I’m thinking about the gamification trend and the issues it raises. Digital games come along that are much more engrossing, compelling, or addictive, than what came before, and with that there’s been talk of a sort of crisis – people being drawn into these games maybe more than is healthy. I guess there’s a tension between how compelling the game is and how much the experience benefits your life as a whole, which only becomes an issue when a game becomes so appealing that you’d even want to spend all of your time playing it. First, do you make this distinction, between games that are good and games that are compelling or addictive?

RG: In the past, I haven’t made that distinction because, with some minor exceptions, if it was addictive, it was good. With the exception only being slot machines or something like that. And that was because there was no reason for me to come out with an addictive, say, version of Solitaire that’s going to drain your money. And if someone likes to zone out on Solitaire – and I may not find that a good game, and you may not find that a good game – but if somebody’s playing a bunch, it might be addictive, but there’s also something positive there. But now I’m being forced to reinterpret that because people are finding ways to get payment hooks into these behaviors that are crossing the line.

JC: And is there an easy way to make that distinction?

RG: Not yet for me. I love the potential, for example, for games with a flexible payment. And it would be hypocritical for me to say otherwise, since that’s what Magic is. But when I see a game that’s “Free to Play” now, alarms go off in my head. And it’s not because I don’t think there can’t be good versions of that – I think, for example, F2P where they give you a really good sample of the game, and your in-game purchase is purchasing extra content – that’s great, I know what I’m getting, and so forth. And I think if you can get scaling input in a game that’s good, again, like Magic. But I think a lot of them are tapping into something which is different, more like this addictive behavior, like slot machines or casino games which are dangerous. I don’t know how to draw the line right now. I know that I’m getting more and more hesitant to play because I know that the game designers and developers are being motivated to provide me a game experience which is not necessarily the best thing for me as a player.

If the proposition is that I can sell you a game once, like a traditional game, like Monopoly, then as a designer I have two choices. I can design a crappy game because once you’ve got it, it’s too late – you’ve already paid for it. And that’s a good short-term solution, and that’s why there are so many sort of licensed games back in the day that didn’t have any legs and weren’t really well-thought-out and so forth. But the other way for me to go is for me to design it so well that you play it again and again, and other people buy it, because you’ve spread it in a viral way.

JC: People play it forever.

RG: In the first case, as a designer, my motivations are not aligned with yours. In the second case, my motivations are exactly aligned with yours – you’re getting the best design possible. The problem with the F2P thing is that the designer’s interests are not aligned all the time with the user’s interests.

JC: Where do you think the burden lies for that shift in motivations? Do you think it’s purely the pressure put on the designers to meet sales goals? Or is there some design confusion – confusing compelling for good somehow? In other words, is it pressure from the business side, or is it a design attitude?

RG: It’s both. I think they go hand in hand. And I’ve been thinking recently of writing a gamer’s manifesto: “This is what I expect when I buy a game.” If I play a Free-to-Play game… there are so many revenue models going around now that don’t make sense to me, but are tapping into something which – I used to believe if people were paying for it they were getting some value out of it – but I’m becoming more and more convinced that that’s not true. A lot of these ideas are still coalescing in my head, so I don’t have any clear answer. But I do have some points of reference.

One of them is from PopCap Games. I’ve worked a little with PopCap in the past, and I’m friends with people who’ve worked there, and I’m told that at one point PopCap found that a large part of the Bejeweled Blitz money was coming from, say, grandma who was spending $5,000 per month on it, or something ridiculous – people with limited or fixed incomes. There were these top heavy players who were spending huge amounts on the game, and they’ve been talked about as the sort of “whales” of the game.

And to PopCap’s credit, my understanding of the situation was that that scared them, and they went out and found these people and asked them why they spent so much, because this was not a good outcome. It’s psychological manipulation – when the player is really not getting any extra value but somehow they’re paying anyway. PopCap was actually looking into how to make people pay less at the top end. Because what you want, of course, is a sort of broader payment that makes people feel like they’re getting their money’s worth. But if the customer is getting basically the same experience but has the opportunity to throw away more, and 1% of the people do decide to do that, I think there’s something really dangerous going on. I can’t draw the line on that, but know that I’m becoming more and more aware that maybe the psychology of the whale is something that shouldn’t be relied on, and is dangerous, and immoral.

I’m certainly hesitant to say that every game that relies on whales is that way. Because, for instance, take Game of War and Clash of Clans: these games are insanelytop-heavy. The amount that the people at the top are paying is very very large. I can at least… in my heart of hearts… I believe it’s the same thing. But I can imagine that at the top level there you’ve got people who have a hell of a lot of money and they just like showing off their money. That’s not something which motivates me, but I can understand them doing it. But Grandma spending her money on the same game experience is not the same.

JC: So, in terms of the distinction between what makes a game good and whatever makes a game compelling or addictive, is the issue for you just the exploitation of these top-end users? Or are there consequences across the board, for example, with a shift in the way games are being designed for or appealing to the ordinary user?

RG: Well, certainly the one I’m most alarmed at is the former – where you’re manipulating the top, and the bottom you’re not really worried about. It’s certainly possible to make a game that’s excellent experience for people at the bottom, but some people go off at the top. And one could argue in fact that of course Magic did that. That people all through it felt like they were getting their money’s worth out of it, but there were certainly some people who spent immense amounts on it, and sure, some of them could’ve been grandmas living on fixed amounts. I would argue that gets into the sort of the morality of a collectible in general because certainly somebody who gets into collecting, whatever, spoons, will spend a lot of money on their spoons. But – again, I can’t put my finger on it – but I think something’s different when they’re playing Bejeweled Blitz, and it’s really the same experience, and there’s really nothing else going on, but you can spend as much money as you like.

JC: So there’s something immoral about not setting a control there.

RG: Yeah, immoral – probably I’m overstepping my bounds saying immoral or not. Because I would not say that people who’ve done so are immoral. For instance, PopCap did it, unintentionally. I think they did a very moral thing – as my understanding goes – by looking into it, and saying “How can we fix this?” What’s immoral, I think, is when people realize what’s going on and try to exploit it, and don’t try to give the right value to the standard game player.

JC: Jane McGonigal identifies two of the central elements of games that cause them to be especially pleasurable, and which can be tapped into and exploited – or, as you say, used as hooks – and these are flow-states and feelings of meaningful conquest (which she calls “fiero“).

RG: The flow state is an interesting one. I’m sure both of them are related to what we’re talking about here: the grandma playing Bejeweled is being charged for her flow state, and in the end that’s what I believe is going on, and I don’t know why she’s been hooked into that particular thing, but there’s lots of ways to get that experience without paying all of her money.

JC: It can exist in terms of those whales exclusively. But it seems to me there’s this other more subtle issue of the conflation of a good game simply with a game that’s addictive or compelling and pulls in the maximum amount of money, a design confusion that has an effect on all the players.

RG: Yeah, there’s all sorts of ways that this manifests itself. There’s many different ways, but I’ll give an example or maybe two. For example, before this F2P became super popular, it was very easy for me to find puzzle games which were richly satisfying, and gave me a good level of difficulty, and I progressed well up a chain. And sometimes they were probabilistic puzzles, like Solitaire, sometimes they were absolute puzzles. Nowadays when I hit a game and it’s in the same space, and it’s free to play, it always has these power-ups, where I can pay, whatever, a dollar for a clue, or a dollar to cheat, and this means that I’m paying to make the game easier, where exactly why I played it before was because I wanted a challenge.

Now the designer is not motivated to give me a challenge which is appropriate to me as a player – where maybe I can choose a difficulty level or something like that – but they’re motivated to give me something which frustrates me. Like in Candy Crush, maybe, maybe I’ve got at 10% chance to solve it, maybe I’ve got a 1% chance of solving it, even if I play perfectly. They’re motivated to give me challenges which aren’t necessarily fun but that I have to pay to get out of. And it’s not that I mind paying – I think paying for games is a good thing, I’m a game designer – it’s what I’m paying for. And I think it’s a vastly better deal for the game player to pay an amount and get a bunch of puzzles that are crafted to the right difficulty, rather than to be given a bunch of puzzles that aren’t fun and you pay to make them fun, and you pay as much as you like to make them exactly where you want. That doesn’t make any sense to me.

JC: Right.

RG: And I think it only exists because it’s hooking in to something that, for lack of a better term, is like taking advantage of an alcoholic.

JC: Right, which is somehow different from what makes a game good.

RG: Yes, and sometimes they overlap and sometimes they don’t. And games are being used as a Trojan horse to bring them in.

JC: It sounds like the fundamental interests of good or profitable business and game design are at odds.

RG: I think right now they definitely are. And I’m hopeful that over time they’ll get into alignment. And there’s a couple ways that can happen. I think this problem in particular could be handled in a number of different ways. One is if people actually recognize and quantify the psychological abuse that I’m talking about, of whale hunting. And the second way is if we can find successful game systems that are delivered to players monetized by being something where people at all levels are interested in paying in a scaled way. And this is like Magic – who knows whether it abused the top end or not – but the players who paid for Magic felt like they got something of value out of it. And it’s also perhaps like a game like, say, Hearthstone, or something like that, or certainly a game like World of Warcraft, where players are getting a certain value out of a game like that. The more successful games like that, the less you have to rely on the whales.

JC: You mentioned that your “addictive personality” gets triggered by some of these online games. When you’ve been playing World of Warcraft or whatever, do you ever get that feeling of “I need to step away now”?

RG: Rarely, rarely. I really think the reason why there’s this 1% that pay a lot, is because there’s something different in these people’s brains. I can show a game to my sister, for example, and not worry about her blowing her savings on it. It’s just not a worry for me. But if I did that to a thousand people, two of them would, who knows. And there’s something going on there with an addictive personality and they press the right buttons and they get in. With me, there’s only a few games I’ve ever quit, because I’ve felt like I could throw as much time as I wanted at them, more than I wanted to.

JC: Right, and some of those were board games.

RG: Most of those are board games. One of them was Quadradius, a very minor online game. Again, maybe it’s something different that I’m describing there; I wasn’t paying to play all the time, but unless I jolted myself out of it, I was going to play all the time.

JC: You’ve described yourself in the past as more of an “explorer” than a “honer.” Do you think this is more of a honer’s vulnerability being exploited?

RG: That’s a good question. You know, since I first came up with this explorer vs. honer, I’ve added two more axes to this chart. And that’s the flow-state seeker and the watcher. And the distinction between those is that the flow-state seeker is the one who wants to play and get into the zone-like state, and that can happen to me, or anyone who is an explorer or a honer, because if you play a game like dominoes all your life, you might play in it and embrace the mental challenge at any given point, or the very next day you might just enjoy the pleasure of being good at something on autopilot.

And these are the honing and getting in a flow state, respectively, so they sort of exist in the same game. And the watcher is someone who – and I guess it’s kind of related to exploring – but they like to do things in games and see what happens. And so they’re the sort of people who, in a game, if there’s the equivalent of a red button that does something crazy, the person who’s trying to win won’t necessarily press that button because they’re trying to break the game down – but the person who’s the watcher might just push that because something crazy happens.

JC: So is the watcher like the “Johnny” in Mark Rosewater’s psychographic? Or is the watcher more passive?

RG: The person who builds weird decks is a good analogy. I think it’s related again to being an explorer, in that you like to explore new things, but I think there’s something a little different going on with this watcher. Because there’s a certain brand of person I know who I empathize with even though I’m not – even though I’m very much an explorer – where they’ll always do the least predictable thing in the game, and if they win it’s a bonus. But if you give them the crazy card, it will probably put them at a disadvantage – they’ll play it because they want to see what happens, they’ll fool themselves into thinking it gives them an advantage.

To get back to your original question, I think the flow-state person is the person most subjected to being the whale. But there probably needs to be another axis added because I think you put your finger on it with McGonigal’s two right there – the flow state and meaningful conquest – both those as motivators are things that are definitely being leveraged for an infinite amount of money. Tapping somebody’s pocketbook if they’ve got the wrong set of mental wiring.

JC: There’s this funny game, I don’t know if you’ve heard of it, called Cookie Clicker.

RG: I know it.

JC: To me it’s funny because it seems so pure in that regard, a game reduced to its most basic psychological levers as its only elements.

RG: I agree.

JC: It’s somehow interesting just to click a cookie for hours, and acquire currency, and spend it, and make cookies at a faster rate.

RG: Yeah. As an exercise it’s an interesting space because it’s so purely this way. There’s other games like that. Like Progess Quest. Are you familiar with that?

JC: No, I don’t know it.

RG: I think late 90’s. And there’s games similar to it. But it was basically just a screensaver; it says “your hero goes out in the fields,” then it says, “He fights an Orc. He defeats the Orc.” Little progress bars are going. “He collects a bone. He fights a Goblin. He collects a spear. He’s got enough stuff. He goes back to town.” And you literally… there’s no input at all. And there were a bunch of people I know who got pretty addicted to it, in the sense that they were constantly watching and comparing their progress. Basically Cookie Clicker and other similar recent games are like that but they make you click constantly.

JC: I keep pressing you on this question because I’m curious about it: somehow those elements – flow and fiero in isolation or relative isolation – seem to characterize a pseudo-game. Even if it isn’t monetized, like Cookie Clicker isn’t, it’s somehow compelling, rather than a good game in an unqualified sense, or it’s a good game, but only tapping a limited and peculiar design space.

RG: I hesitate by the “not a very good game” because again I think some people are enjoying them. I think there’s a psychological factor which people are taking advantage of for money that has not been applied to my knowledge to Cookie Clicker. So they’ve got this game that’s perhaps a good engine for taking advantage of those people – for all I know they are – but the other people who are playing it, they’re being driven by something else, they’re being driven by this flow state. Which is I think just fine. It’s the actually the tapping into people’s pocketbooks and saying “I’ve provided you a flow state, now pay me all your money” that only works on some people and is maybe the issue.

JC: So besides the production of flow, and the production of fiero, what makes a game good?

RG: Well, sometimes it’s hard to separate those elements from characteristics of the game. For example, a good game will give you flow – it has that capability often – so if you point to something that contributes to a good game, it also contributes indirectly to flow. Mechanics – those are the very high-level characteristics of a game. Social interaction – in card games or board games, these are broadly the most important parts of a game – they allow people to interact in a framework which is safe and meaningful. If the game creates a community or contributes to a community, that’s a great high-level element of a game.

When you start digging down deeper into a game, and you start looking for mechanics that bring out these things, and one of the things I like to find in a game is, for example, games that have a lot of luck but a lot of skill also. I like a lot of luck in my game because you can play it with a very broad audience and get very interesting situations; you don’t have to find someone who’s about the same level as you. And I like a lot of skill because I like to think about games and feel like I’m improving my play. But those by themselves of course don’t create a community or contribute to a community, but I think that a game like that has more of a chance to be engaging, and will then bring up meaningful conquests and flow states.

JC: What metrics can you reference to judge whether a game is better or worse than another game? Is it just that there’s different games for different types of people, or are you ever willing to say that a game may sell well but it’s just not a good game period?

RG: No, I’m pretty much not willing to say that. If a game is selling, it’s meeting someone’s needs. And I think it’s an easy out to say, for example, “Oh, Monopoly is not a good game but it just happened to be the only game around or something.” I think it’s cheap. What you have to do is really look at why that game works for the people who are playing it, and not dismiss them or belittle their taste. I find that that’s a very useful attitude for me as a game designer, because then, even though a game like Monopoly may not appeal to me, I can look at it, and if I’m honest with myself, I can figure out what’s appealing to this audience, and I can either learn to appreciate it – which means that I will now be a broader game player – or, as a designer, incorporate that facet into my game, without incorporating those facets that I don’t think are good.

JC: But what if you applied that same principle to something like junk food or McDonald’s? On the one hand, they definitely have their appeal, but on the other, the appeal has to be heavily qualified due to detrimental aspects that aren’t always fully appreciated by the customer.

RG: I think there are other metrics than just how popular it is, certainly, because a game may appeal to a very broad group of people for some reason and it’s not being serviced by other games, so a lot of people like it and it’s very popular, but really it might only have that one aspect going for it, so it would be hard to say that that makes it broadly a good game.

But I tend to be in the camp that McDonald’s is easy to put down in the same way that Monopoly is, but that it’s got a lot of things going for it too. It’s easy when one has the schedule, flexibility, money, and resources to go to a lot of different places and satisfy different eating needs in a lot of different ways, but McDonald’s came about and continues to this day to service people who don’t have a lot of time, have a wide variety of people in the family to feed, and don’t have a lot of money.

But I’m sure that’s not exactly your point, because there is such a thing that is unhealthy food, and food that you shouldn’t rely on too much, and yeah, there are mechanics in games that I would say are similar – people who get addicted, you can make an analogy to them and people who get addicted to very sugary foods that aren’t good for your body. And maybe you can make parallels to the same mental issues, where you have binge-eating, and binge-playing. Yeah, there probably are parallels there that you could draw.

JC: Where do you stand on the diagnosis of powerful games, like World of Warcraft, as presenting a sort of crisis? That they’re exciting in an unprecedented way, but also dangerous?

RG: I mean, there’s certainly some things to think about there, and I think that people have various degrees of obsessive reaction to different worlds, but I think that it’s also often overstated. For example, I know a lot of people who have invested an amount of time into a game like World of Warcraft that would shock my parents or something. But I think they think, and I believe, that they’ve found it enriching. Whereas someone else might get real pleasure from going out hiking, they’ve got real pleasure from what they were doing, and to pass judgment on that to say they really should be out hiking…if they’re reasonably healthy, in other regards, they’re getting something out of this.

Where it gets to a level where one might think of it as an illness, I think you should take a look at, I also think that illness would be exploited in other ways if those games weren’t there, and to level the blame at where their time is going is unfair. I think time spent playing games can be very enriching and very rewarding and there will be people who break the bounds of what’s sensible there, but that’s going to happen – you brought up McDonald’s earlier, eating McDonald’s I think is just fine also, but there are people who break the bounds and end up in a bad place because that’s all they do.

JC: Does the game designer have any responsibility to consider whether the game they’re making is addictive or compelling beyond what’s healthy?

RG: Yeah, I think it would be a step back for games if game designers had to do that, in that, certainly, my most pleasurable moments in games have come from games where it seemed unbounded how much time I could put in or how much I could throw myself in. Just because somebody becomes completely obsessed with a game like Chess, and reads opening books all day long, and lives for a Chess tournament, why would you take that away from them because you don’t think they should be spending so much time playing Chess? It seems ridiculous. What makes sense to me, though, tying back to what we were saying earlier, is that I do think that the designers do have some responsibility to the way players are spending their money. If you’re making money off of something which amounts to something like gambling addiction, that’s really bad.

[JC’s Note: After this interview, Richard wrote the “Game Player’s Manifesto” mentioned previously. His position is the same as given above: the relevant issue is largely game design that deliberately preys on top-end users. He names these games “Skinnerware”, after the Skinner Box, an experimental setting in which pleasurable or painful stimulation conditions a subject toward given behaviors. In other words, then, Skinnerware treats top-end users like animals in a test chamber who, in response to the right stimulation, can be made to behave in ultimately self-harming ways at the service of another purpose.

This is an extreme case of the possible disparity between the designer’s motivations and the user’s, discussed above. Richard mentioned two possible avenues that a game producer might take in order to turn a profit – to actually make a great game, or to make something resembling a great game. In the second approach, the designer and user’s motivations turn out to be at odds. In the old days of analogue games, one example of this was licensed games that looked good but weren’t well thought-out. Now, one example is “Free to Play” games with puzzles optimized for extracting a frustration-relieving payment, rather than for a puzzle built to scale with the player’s skill level. Yet, Richard draws a distinction between the extreme cases – like whale-hunting – in which a vulnerable party is taken advantage of, and the less extreme cases, that only result in the proliferation of poorer – or maybe just narrower – game experiences. In the latter, the customer would have sufficient agency to make a fully informed decision about the exchange on offer, of money for a certain kind of satisfaction.

Much of the complexity surrounding the issue comes from this difficult issue of agency – the premise that all customers have perfect information about the exchange being offered. On one hand, this is generally what has to be expected of adults. On the other, marketing depends on the premise that the same product can be made to be perceived in different ways – its actual benefit being not necessarily transparent.]

JC: In your retelling of the conception of Magic, talking about the setting, you expressed a preference for a “multiverse,” a “system of worlds that was incredibly large and permitted strange interactions between the universes in it.” Mirage, like the earlier sets, has the feeling of occurring in an open multiverse. Cards occasionally allude to a contained narrative or famous figures but these never take center stage. Narrative richness is implied, with room left to be filled by the imagination. Can you talk about the role of narrative in games, and trading card games specifically?

RG: There are a lot of different things that are meant by stories in games, and a lot of people react strongly to what they call “story.” I think that oftentimes there’s confusion between a story as in a linear narrative, and a story as in an atmosphere. For example, in Magic, there was an atmosphere or a flavor between the different magics and the creatures floating around, and you could look at it and say these are the elements you could tell a story with, but that’s distinct from something like Final Fantasy, where’s there’s a linear narrative with a beginning, middle, and end, and it has character development in a particular way, and there may be branches, you may have a handful of different endings or different ways to solve something, but really there’s not a lot variety to the way the narrative unfolds. So I want to draw a distinction between story as atmosphere and story as narrative.

I think games are excellent vehicles for atmosphere, but I think they’re by and large pretty hard to get a good story in, and that’s because in stories the player lacks agency. If you tell a story, you’ve got a sequence of events that you describe, where if you have players make decisions, if they make different decisions than you expected, you’re not going to get as good of a story. And allowing players decisions in a story is against, in many ways, the whole way narrative has always worked. Now, there are ways to shoehorn them together, and you get people who get very satisfying experiences out of something like Final Fantasy, but I think it’s a difficult thing, and often when people try to put in story in the linear-narrative sense, they’re effectively taking agency away from the player, which is one of the fundamental things games are strong about: giving agency to the player. And so I draw that distinction: atmosphere is more natural to games than linear story as such.

In TCGs I think that carries also. They’re exceptionally poor vehicles for a linear narrative story, but they’re excellent for atmosphere. One of the tools that we learned with Magic in the early days – I don’t think it was carried on, but one of the cool things we did with it – we thought of how you would tell a story if it was introduced in a random way, and we thought “well, that’s kind of what happens in archaeology.” You dig through, and it doesn’t tell you a coherent narrative of the people who live there, or the society that was there, but you get pieces of it, and you put together your own narrative. And that felt to me much more like a TCG in particular and games in general where you might run into all sorts of different elements of an underlying story, but it’s your responsibility to piece it together into a narrative – it isn’t introduced in a traditional sense of a beginning, middle, and end with a character arc and so forth. Antiquities is where we really tried to do that, where we didn’t tell you the Brothers’ War in a traditional arc, what we did was give you little pieces of it and you have to piece together the story.

JC: The way I read the history of the game, in the years following that game’s immediate success, you can sense a huge explosion of resources, and that you guys were having to very quickly figure out the next steps, both creatively and in terms of business. So two different transitions seem to be happening at once. First, the game starts to come into creative focus, and the set that reflects that the most is Mirage. In the very first sets, there’s an open and diverse approach to art and the flavor text that’s really charming, but could be accused of being a bit of a hodgepodge. But by Mirage that same approach is starting to become cohesive.

The other transition is totally different – it’s the game finding its business legs. As the story goes, Peter Adkinson initially had rebellious and radical counter-corporate ambitions for Wizards and for its approach to game design. At some point – around the same time we’re talking about – he became disillusioned with this prospect, and came to terms with the need to develop Magic according to more traditional branding norms. Can you speak to that experimental spirit of the early days, and the transition away from it?

RG: Well, it was a certainly a turbulent time for Wizards of the Coast. And peoples’ philosophies about where we should go and what we could do were widely varied. It took about three years for most of the company to be convinced that what we really had was Magic and that that was where we should really put our energy. Until then, the people that were in the company were young and had very quickly become successful and so they thought that everything they did would be successful. And so they worked on educational games, role-playing games, hobby games, broad-market games, party games, every sort of game, and things outside of games as well. There was a theater department at Wizards! It’s really crazy what young people who get a lot of money and they think that everything they do will be successful end up doing. And there was a certain point where Peter had to say, “Look, this is all out of hand, and we’re going to focus on what we do really well, and do our best by Magic.” And at that point, the game’s belt was really tightened a lot, and there was a lot of focus placed onMagic.

I will say that while I don’t think I would have advocated setting up theater departments, and there were a lot of things that I thought were wastes of time, I was not immune to this in that I went from designing Magic to designing other TCGs and other board games very quickly–

JC: – You changed gears because you were somewhat put off by the experimental environment?

RG: No, I’m saying that I thought the experimental environment was a travesty. I thought very early on that it was a huge waste of time and money. But I was saying that I wasn’t completely immune to it either because I focused most of my design effort on new card games, new TCGs, new board games, because I saw TCGs as being an entire genre of game, and wanted to set down more flags than just Magic. I think for my own personal edification that was a good move because I wanted to design a lot of different games, I didn’t want to design just Magic; but clearly the place I should’ve been placing my effort, if I was only concerned with the health of the company, in retrospect, was Magic, since this was the most important thing Wizards had going for it.

JC: Were you around then at the time when that branding initiative was happening?

RG: Yeah, I was definitely there at the time and part of those decisions. Yeah, there are a number of different facets I could respond to about that, but I’ll choose one I was personally involved with.

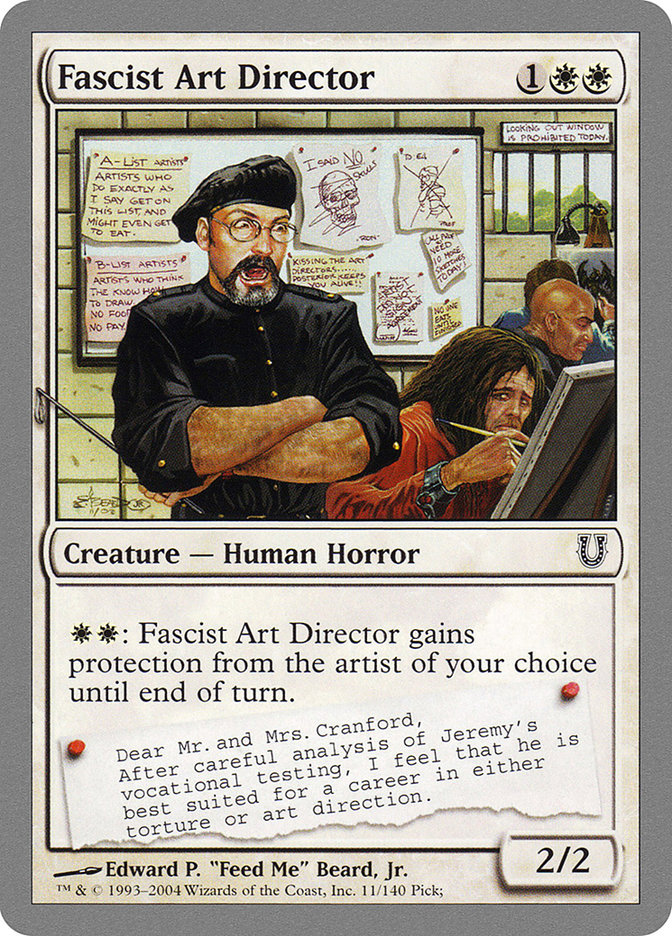

In the beginning with Magic, I wanted to give the artists as much room for creativity as possible. And so the initial art description was often just the title of the card. And that was intentional, I did not say draw a giant or this or that, I would give them a title, and sometimes if the title was ambiguous, I would explain what the idea of the card was, but I would let them draw it. So you would end up with things like Stream of Life, I had no idea they were going to draw a literal stream for that – that seemed ridiculous.

But the reason why I did that was not laziness but because I figured that artists are, sort of by definition, a creative lot, and I wanted them to be creative on my behalf, and I thought that if there were a lot of people interpreting things in a lot of different ways you’d end up with a lot richer world. And think that gets back to the multiverse thing. The more it’s a multiverse – lots of different universes, rather than a specific universe – the more you can look at inconsistencies and say this is part of the dark world, or this is part of this world which looks a little like Alice in Wonderland, or something like that. So I think we got what I was after which was a really broad set of arts and looks. And in particular I was really after art which people loved and hated which I thought was a good thing and better than art that everybody thought was okay.Because love and hate is what drives a good economy. If everybody values things the same way, there is no economy, and so having different aesthetics suggests that you want people to value even the art in different ways, and that’s where we began.

Where we ended up is… Well, quite reasonably, if you’re going to do fiction and comic books and movies and other spinoff games, you want to have a look, and in the original game the only look you really had is the mana symbols and the card frames, and everything else was just a mish-mash of fantasy figures. For example, you could look at Goblins, and every artists drew them differently – they were different species – and while that was okay with me, in the long run, if you’re trying to build a brand, that’s not useful. And there was a certain point, and that’s probably around Weatherlight, where there was much more of a guideline of “this is what the world looks like, this is what a goblin looks like,” and card art began being assigned in ways which made the artist much more an illustrator to demand than someone who’s describing big-concept creativity.

JC: So if we were to look at two different paradigms for Magic, Mirage and pre-Mirage being one, where you preserve that very open feel, and Weatherlight and post-Weatherlight being another, where you have the storyline with the ship and the characters on it and a tight style guide, what’s your opinion on the tradeoffs between them?

RG: In the long run there is a concession to brand which is necessary and good. I think the history of Magic is probably a good one in that, starting out wild like it was, helped us build a brand by getting people excited in that “love/hate” way. But then, when the value of the brand actually begins to eclipse the needs of, really, individual players, then you have to start broadening your palette and going further.

So, I think the way the brand went for my taste is probably too narrow now, but it was a direction the game had to go, and certainly at least some steps in that way were necessary. And if I were completely in charge, I still would’ve taken steps in that direction. The narrative perspective, though, as far as narrative was concerned, was not successful from a gameplay point of view. I think the “games-as-atmosphere” versus “games-as-story” has stood the test of time. And you see that even though they do use narrative in conjunction with the cards, the cards – I believe – these days are much more in the area of a bunch of different atmospheric elements rather than “in this set we tell the story of this ship and this captain and his mates” and so forth.

JC: Do you have a perspective of the recent design outlook – The New World Order as it’s called? Making the commons simpler and deferring the complexity to the higher rarities?

RG: To me that’s the Old World Order! That’s the way the game was designed in the first place. And it’s very natural over time that as you make more and more cards they become more complex over time. And I’ve heard many stories from designers – and this isn’t even the first time, it’s over the years people have gone back and played Magic as it was first released – and they say “Wow, this is a lot of fun, even though the cards are so simple.” And you don’t need the sort of complexity which you see on the rare cards to get an interesting experience. The philosophy originally was that the common cards are simple and broad and the rare cards are spice, and you didn’t want to see a Magic set that was entirely spice, but you wanted to see some meat and potatoes as well.

JC: One thing that’s come along with the New Order (or the new return to the old one) is a more rigid design skeleton. Every set seems to have one Shock at common, one Giant Growth at common, and so on. The pattern’s become tighter than it has been at other times in the past. Are you content with the game falling into an evergreen pattern, or do you miss a more free-form experimentality that it had in the earlier days?

RG: I see everything as always changing, so if for a period of time there’s this narrower view, I think that’s fine. In fact, I’ll say that a long time ago when it was the Wild West in Magic development, our views on it were probably very narrow also, in that, for instance, Ice Age – the first standalone expansion after Magic came out – there was a lot of debate about how many reprints to have. My philosophy, and that of a lot of the designers, was that there should be many, many more repeats than people who wanted to bust open all new cards wanted. We definitely erred on the side of as many new cards as we could put in. But there were many times when we were playing it and over 50% of the cards were the same because the game plays entirely different if you have this skeleton but you have… even having things at different rarities changes the game, even if it’s the same card. So you don’t need to make a lot of changes to get a huge amount of variety out of the system. And so in a lot of ways I felt like adding… like trying to make everything new all the time… was making the game needlessly complicated. Why do we need your Grizzly Bears to have some crap ability that hardly ever matters just to make it different? It just makes it needlessly complicated. And so I’d say that that I like seeing a wide amount of variety, but at the same time I don’t want to see needless variety.

Also, even if there is this framework which is kept consistent, within that framework you’re going to have things like different formats, which offer variety because people can play Constructed in all sorts of different ways, and Limited in all sorts of different ways, or use different sets, and if they really want to push the craziness level, they can play Elder Dragon and things like that, and I’ve noticed the company’s been supporting things like that in recent years.

JC: The way people play Magic now, because of technology, is different from the original experience of the game. What do you make of the changing setting for the game?

RG: I think board games and cards games still have something which computer games don’t have – “around the table” social interaction – which I think is quite important. The digital age has benefited the game as much as it’s cost it through competition. You look at what’s going on today and you might think, “Wow, this is a different world from the one in which it launched,” and in many ways it is, but one of the things that really contributed to Magic‘s success was the digital age and the newsgroups and the online interest in this because that was a reflection of the community that was so important to the game. You can’t have community without communication, and communication has never been easier. So, around the kitchen table, you may find that people play a more cookie-cutter Magic than originally, but at the same time those people have access to far, far more variations on how to play than they did when the game first came out, because people play all sorts of different ways, and they like to share them, talk about them, and give all sorts of feedback. So the tools exist for players to really take ownership of the game in ways which they didn’t have before. So I think, on balance, if anything, the range of options to players is much bigger now than it used to be and the ability to customize their experience is greater than it’s ever been before.

JC: What are your hopes for the future of Magic?

RG: My hopes on the future is that it keeps on being an evergreen, in that I can return to the game in ten years and get an exciting experience which is familiar but at the same time fresh. That the tournament circuit which has generated so much excitement in the game continues to thrive. So really, beyond that, I think in the past it’s been working fine and I hope it just isn’t broken by… – I’ve got trepidation about this planned movie, you know, Magic: The Movie, screwing up the flavor and things – but I think it’s a been in a great place for a long time and it’s not big changes that you need to see.