There is much to discuss today. First, I’ll begin by taking a look at the controversial issue of collusion and whether it should be legal, which has stirred up quite a bit of debate in the Vintage community. Second, I’ll show you my approach to Dark Depths decks in Vintage. Third, I’ll discuss some Magic theory, and address some points recently raised in the Vintage community. Finally, I’ll give you the insider’s look at the StarCityGames.com $5000 Legacy Open results from Philly, including hot new decklists. Let’s go!

Collusion

One of the hot topics in the Vintage community right now is collusion. Under the tournament floor rules, Collusion is prohibited. Vintage expert and personality Robert Vroman argues that Collusion should be legal. Many others have jumped on board in agreement.

The essence of his argument is libertarian: Vroman suggests that collusion is self-regulating, welfare-maximizing, and therefore not harmful. His argument works like this: players would only accept a bribe to concede if it were in their best interests to do so. It is in their best interests if they would make more money on account of the bribe than they expect to make more in tournament prizes. Because most players overestimate their expected payout, to pay off all the opponents in a tournament would necessarily involve a greater outlay than the expected profits. For that reason, everyone would be better off except for the player who bribed their opponents to get there. But if that person really valued the victory more than the prize, then they got what they wanted and no one would complain because they made more money than they otherwise would have. But what about the fact that most people in Vintage play because they enjoy the format, and not to maximize their expected monetary profits? Simple: If one of the opponents valued the pride of victory more than the prize of victory, then they could simply refuse the bribe and play for the win. In short, collusion is self-regulating and welfare-maximizing. People have the choice to refuse a bribe or to accept, whichever they view is in their best interest. No one is harmed.

There are other facets to this argument that you can read for yourself. I presented all of the essential argumentation here.

Vroman’s argument is fascinating — and it’s one that has crossed my mind before. But there is one fundamental flaw. Vroman’s argument that no one is harmed is actually wrong. While it may be true that the colluding parties may be better off as a result of the agreement to collude, third-parties will be frequently harmed. The reason is simple: profit-maximizing collusion is always zero-sum. The profit-maximization comes at the expense of some other person. The reason to collude is to advance the player who has a better shot at winning the next match. Thus, the next round opponent, particularly in a Top 8, will have to face a worse matchup as a result of the collusion than if the match had played out regularly. This is the motive for colluding. In essence, collusion incentivizes rigging Top 8 outcomes and is unfair. It gives an unfair advantage to certain players.

Vroman proposes several counter-arguments. First, he suggests that although what happens inside of a match determined by collusion may not be random, it must be considered random to the opponent, who could have faced this matchup anyway, and players must be prepared to face anything in the field. If you play a deck with a particularly bad matchup, then that is your fault. In any case, he argues that the match will be determined by technical play skill and sideboard decisions.

Second, he suggests that this is no different than intentionally drawing in the final swiss rounds: some players are locked out from making the cut, which they would not have been had you played it out. Third, Vroman argues that this problem can be regulated or minimized by requiring that collusion be decided before the round begins.

None of these counterarguments are convincing. Regarding the first point, the most important skill in Vintage Magic, and perhaps Magic generally, is deck selection. Every deck has good and bad matchups. Skilled players select decks that maximize their favorable matchups and minimize their bad matchups through a careful understanding of the metagame and metagame dynamics. To take a particularly extreme version of this problem, a clever player would bring Paper to a metagame infested with Rock and Scissors. The Top 8 is likely to be very few bad matchups and mostly good matchups. You can expect that as you ascend through the Top 8, let alone the swiss rounds, your chances of finding good matchups increase. Collusion would allow the Rock players to collude with Scissors to advance the Scissors player to face you. To say that players should consider their opponents to be random when it is the product of collusion is wrong, when the object of the collusion was to advance the player who is your worst matchup of the two. This is unfair because it diminishes a crucial skill in Magic, metagaming and metagame positioning. Instead, it pushes players to play decks that have no bad matchups, and forgo decks that have particularly good matchups at the expense of a few bad matchups, among other problems. But even then, the issue isn’t addressed because every deck has better or worse matchups. Even with 51-49 matchups, there is an incentive to collude.

The second counter-argument also fails because IDs are not unfair. There is a qualitative fairness difference between locking some people out simply on account of their accumulated points and targeting a particular person because of their deck choice. Rational, profit-maximizing collusion is always undertaken to disadvantage a particular player in a game (match of Magic) on account of the deck that they are playing. Intentional draws are not calculated for the purpose of disadvantaging another player in a game of Magic based upon the deck the next round opponent is playing. No consideration of another player’s deck or other in-game considerations are brought to bear. It’s simple tournament math and has nothing to do with the strategy or tactics of Magic: the Gathering. In one case, people are being treated differently on the basis of their deck choice. In the other, everyone is being treated the same on the basis of their deck choice.

The third counter-argument also fails because knowledge of the players and the archetypes is enough to predict the outcome of the match most of the time. It is often the case that there is a superior Vintage player playing a favorable matchup.

The reality is that collusion is probably far more widespread in Vintage than other formats on account of several key facts. First, many, if not most, Vintage tournaments are unsanctioned to permit proxies. This means that there is no organizing body like the DCI to investigate or punish collusion. Second, many Vintage players don’t feel that there is anything wrong with collusion, and engage in it freely. This is partly because most Vintage tournaments are small scale, and Top 4 splits are quite common, both to maximize expected value to the players and to save time. Also, regional teams are often dominant in local metagames and can control the flow of Top 8s by defeating certain players and splitting the remaining prizes.

Collusion is a problem in Vintage, and it needs to be addressed through greater vigilance.

Hexmage Depths

Everyone knew that Vampire Hexmage plus Dark Depths was a broken combo. I said in my Zendikar set review that this combo has potential Eternal applications. It’s already made a major Legacy Top 8.

The possibilities in Vintage are numerous, although the likely impact is far more limited. That said, I think it could become the basis for a solid budget archetype.

Up and coming Swiss Vintage player Patrick Wild suggested this version of the deck, in Mono Black:

Creatures (11)

Lands (19)

Spells (30)

Patrick clearly tried to cram all of the new Zendikar goodies into one archetype. For that, kudos; I just listed them in my set review.

There are a few things I like about this deck. It has the full complement of Duress effects and Null Rods, it has the correct tutors, and looks generally well built.

There are a few things I don’t like about it:

The manabase is far too light. It’s simply too greedy to think that you can get away with only 12 reusable sources of Black mana.

I’m also skeptical of the number of Sadistic Sacrament and the Cabal Rituals used to support them. I tested, rather extensively, a Mono Black budget deck about a year ago.

That was my first article on Vintage budget decks, and lead to the Christmas Beatings deck, the now-quite-popular G/W Beats deck, and most recently, Meandeck Beats.

In my testing, Cabal Ritual was not very good. I understand that he is using Cabal Ritual to fuel Sadistic Sacrament, but it’s still iffy.

Keeping the deck budget, here is my proposed changes:

Creatures (8)

Lands (24)

Spells (28)

Explanatory notes:

• I cut Tendrils, and therefore I also cut Yawgmoth’s Will, which I moved to the sideboard. Yawgmoth’s Will is still really good in this deck, but I wouldn’t add it back in until you figured out exactly what the next weakest link is.

• I reduced the number of Chalice to 3. Chalice is, I believe, better than Sacrament.

• I think Gatekeeper is fine, but Diabolic Edict might simply be better on account of the tempo issue. You will be tight for Black mana at certain points in the game, and need your Edict effect.

Since I always get questions about how to build these decks if you can work with 5-10 proxies, here are some other options:

Hexmage/Depths, Mono Black, 5-Proxy Version

4 Null Rod

4 Dark Confidant

4 Vampire Hexmage

1 Necropotence

4 Dark Ritual

1 Demonic Consultation

2 Diabolic Edict

2 Sadistic Sacrament

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Imperial Seal

4 Duress

4 Thoughtseize

4 Dark Depths

3 Urborg, Tomb of Yawgmoth

1 Lotus Petal

1 Mox Jet

1 Black Lotus

3 Swamp

4 Snow-Covered Swamp

2 Polluted Delta

2 Bloodstained Mire

1 Marsh Flats

1 Strip Mine

4 Wasteland

Hexmage-Depths, UB, 5-Proxy Variant

4 Null Rod

4 Dark Confidant

4 Vampire Hexmage

1 Necropotence

4 Dark Ritual

1 Demonic Consultation

2 Diabolic Edict

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Time Walk

1 Brainstorm

1 Ponder

1 Vampiric Tutor

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Imperial Seal

4 Duress

3 Thoughtseize

4 Dark Depths

3 Urborg, Tomb of Yawgmoth

1 Mox Sapphire

1 Mox Jet

1 Black Lotus

4 Underground Sea

2 Snow-Covered Swamp

1 Island

4 Polluted Delta

1 Strip Mine

4 Wasteland

There are many other possibilities. Crop Rotation can find Dark Depths and Goyf is a great beater, if you are thinking about a Green splash. Enjoy.

Magic Theory: Active versus Reactive

A Fish player posted a rambling, long-winded essay on the Mana Drain on how Fish players should focus on including as many disruptive cards as possible, an obvious truism for Fish, Beats, and Stax players alike. However, in his theorizing, he made some rather astounding, yet sadly common, claims. Among them were the claims that cards used in Fish decks are not good cards, including Null Rod and Force of Will.

By responding to claims such as this, I can sharpen my own views of Magic. At first, this individual talked about the card disadvantage of Force of Will, and seemed to suggest that the only reason Force of Will sees play is because of the speed of the format. I tried to point out that while Force of Will may be card disadvantageous, the tempo advantage often translates into enormous card advantage or card quality that leads to game wins. It soon became clear that this person’s lens for understanding whether a card is ‘good’ or not is whether a card is ‘flashy,’ or ‘showy,’ and a card’s proximity to what they perceived to be victorious game states.

I tried to explain that this is the wrong way to judge a card’s value. Rather, the metric for judging whether a card is good or not is its ability to contribute to game, match, and tournament victories.

Eventually, this person conceded that Force of Will may be a good card, and explained that they didn’t want that issue to consume the broader theory they were espousing for how to design Fish decks.

I realized something very important: the two discussions couldn’t be divorced. The discussion of what we mean by ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cards and how we know whether a card falls into one of those categories affects the rest of the discussion. For example, in this person’s view, since Fish should only run ‘bad’ cards, only bad cards should be included. Yet if this person’s view of what is good and bad was flawed, then it follows that this person’s way of understanding Fish was similarly flawed.

I recount this exchange for one important reason: the way in which we know things (our epistemology) becomes a lens by which we evaluate other things, and it’s not just this poor soul that falls into this trap. For example, in the discussion over Meandeck Beats, a debate arose over whether ‘hate’ decks, using less ‘powerful’ cards, are less adaptable in the metagame. I replied by questioning the very terms of the debate. Yet these terms are so entrenched that it’s almost impossible to have this debate without fundamentally questioning a player’s epistemology, their way of knowing the world of Magic.

I promised then that I would write an article, laying out the dominant epistemology in Magic, and suggest a more accurate one. I started doing this with my article last December, “Understanding Magic.” While I will do so in the near future, as a follow-up to that piece, I think it’s worthwhile sketching out some of the main features right now.

First of all, the poster stepped back from describing certain cards as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and tried to use the dichotomy “offensive” versus “defensive.” Another poster stepped into the fray and suggested the terminology “active” and “reactive.” My basic claim is that these terms, like: “power,” “offensive,” “defensive,” or even “proactive” and “reactive” are not helpful. In fact, these terms, upon close inspection, have no clear meaning. And even when they do, they are misleading.

For example, consider the definition this individual provided for these terms:

1) A card is “active” if it seeks to actively win the game, or to actively enable further resolution of your strategic plan.

2) A card is “reactive” if it seeks to hinder an opponent’s strategy to actively win the game.

These definitions are predicated on incorrect but widespread understandings of Magic. What I pointed out was that all reactive cards are active cards, under this definition. In other words, the set of active card includes all reactive cards. It’s not that these definitions are somehow ‘false,’ in the sense that they are wrong by definition. It’s just that they are not meaningful. Reactive cards become a subset of active cards, and thus the project, to provide two mostly mutually exclusive categories, fails.

The reason is simple: Cards that are defined as reactive contribute to game wins in precisely the same way as cards that are active. Not losing the game = winning the game. The two are linked by definition. This can be easily seen when your opponent is playing this deck:

22 Island

37 Counterspell

1 Air Elemental

If you counter the Air Elemental (or kill it), and were on the draw, you will win the game. In that way, cards defined as ‘reactive’ actively win the game. For a while, the poster contested this, utilizing the flawed model of causality I described in my article “Understanding Magic.”

I used this example:

I play Tarmogoyf. My opponent plays Path to Exile. I Force of Will Path. The Force of Will casually contributed to the game win. It was reactive card, but it ultimately, also, active. The Force contributed the game win by protecting the Goyf. This is clearer with other examples, such as the Air Elemental example, or by locking an opponent without Trinisphere and Smokestack. By preventing your opponent from winning, you will ultimately win the game. It’s even more evident in a simple case of a card that says: ‘I win the game,’ such as Coalition Victory. Forcing Coalition Victory (with the conditions satisfied) is a necessary condition to winning the game, and clearly a causal contributor to winning the game since necessary conditions are obviously casually connected to winning the game. However, contributing to a game win say, by Forcing Path to Exile, is also a causal factor. There are many forms of causation, but contributory causation is a form of causation, and it’s the most important in magic, since no cards in Magic do anything by themselves.

The poster objected that my model of causality means that everything causally contributes to a game win, including scratching my nose. But this is absurd. Whether it’s raining or not outside is not a causal factor to whether you win a game inside the tournament hall. Not everything is a causal factor — only those things that actually contribute to a game win. This is counter-intuitive to many people, yet it is correct. Things that contribute to particular outcomes are causal factors.

But as I pointed out in my article Understanding Magic with the example of Thoughtseize, this doesn’t mean that this view of causality precludes useful information: Clearly, from a perspective of trying to understand how to improve a deck by questioning the presence of certain cards or evaluating our play, questioning the presence of Black mana may make less sense than focusing on the play of Thoughtseize. But from a strictly analytical perspective of causation, they are both causes.

Similarly, while shuffling a deck contributes to game outcomes, as anyone who has lost to a lucky topdeck can attest, it doesn’t make sense to focus on that as a practical matter, even though it is a causal factor in as a factual matter.

Here are the new definitions:

A “reactive” role can be defined as a role played by an entity that is dependent upon the existence of an entity, or entities, under the opponent’s present, past, or future control.

An “active” role can be defined as a role played by an entity that is not dependent upon the existence of an entity, or entities, under the opponent’s present, past, or future control.

In this case, the definitions are mutually exclusive, but, again, misleading and unhelpful. It is misleading because these definitions mean the same thing as ‘disruptive’ versus ‘non-disruptive,’ and those labels make a helluva lot more sense. Using ‘active’ and ‘reactive’ as terms for these definitions instead of disruptive versus non-disruptive can only produce confusion. This is what I pointed out in the middle of the discussion: it is a far more useful, and accurate frame, to describe the difference as disruptive versus non-disruptive. Fish decks need to be as disruptive as possible. Classifying Fish cards as “good” versus “bad” or ‘active’ versus ‘reactive,’ is much less helpful than the frame I supplied. This focuses your attention on the thing that really matters: how effectively you disrupt your opponent, not simply how you ‘react’ to them. Trinisphere? Clearly disruptive. Jester’s Cap? Clearly disruptive. Force of Will? Clearly disruptive.

Our terminology matters because it becomes a lens by which we evaluate and know the world. We filter information into categories and using these categories we create meaning. In that way, decks known as ‘hate’ decks get a rap for having ‘bad’ cards and for being ‘less powerful.’ Yet, it’s simply untrue.

The StarCityGames.com $5000 Legacy Open Philadelphia

By now, you’ve seen the Top 16 results. SCG sent me all of the decklists. Here’s the entire field, 1st through 147th place:

Peters, Brian — Mono-White Stax

Bishop, James — Canadian Threshold

Barlett, Matthew — Dredge

Mosier, Jonathan — UGW Countertop-Goyf w/ Natural Order

Hunt, Timothy — UGB Countertop-Goyf

Phillips, Cedric — Belcher Combo

Woltereck, Chris — 42 Land

Adams, Ken — B/g Hexmage Depths

Pau, Vincent — UGWR Counterbalance-Goyf w/ Natural Order

Tocco, Mark — Ad Nauseam

Bertoncini, Alex — Ug Merfolk

Hartten, Chris — U/B/r Bitterblossom Control

Reiners, Mitchell — Zoo

Cusick, Robert — Zoo

Imperiale, Jason — Dredge

DiClemente, Joe — Zoo

Sagnay, Philip — BGW Aggro Control

Zhang, David — U/w Merfolk

Marmulstein, Rion M — Goyf Sligh

Montaruli, Michael D — Canadian Threshold

Hatfield, Alix — Zoo

Lodovichetti, Dominic — Zoo

Bode, Jonathan — Counterbalance-Depths

Jordan, Dan — Dredge

Dorman, Scott — Pox

Weinberger, Andrew — UG Counterbalance-Goyf

Davis, Jim — Goblins (G/r)

Feigley, Brian — UWB Landstill

Cutick, Joe — Sligh

Troyanosky, Michael — Stompy

Coval, Brian — Canadian Threshold

Copobianco, Nick — UG Counterbalance-Goyf Painter

Swindell, Tom — Ad Nauseam

Higgenbottom, Jim — Ad Nauseam

Najman, Adam — Mono Black

Ferrando, Matt — UGR Counterbalance-Goyf

Robbins, Sean — Canadian Threshold

Conway, Scott — UGB Countertop-Goyf

Azzano, Doug — Life Combo

Klomparens, Jacob — Merfolk

Price, David — UGW Terra-Goyf

Hatfield, Jesse — Zoo

Wertz, Walter — Ad Nauseam

Abendroth, Allen — Dragon Stompy

Dixon, Tom — Canadian Threshold

Lam, Randall — Ad Nauseam

Levin, Drew — High Tide Combo

Jannen, Bill — Zoo

Jones, Kevin — Goblins (mono red)

Bourgoin, Ryan — BGW Aggro Control

Longo, Paul — BGW Aggro Control

Carpenter, Stephen — UGBW Countertop-Goyf+B16

Mirsberger, Donald — Bg Aggro

Rae, Dan — UGW Countertop-Goyf w/ Natural Order

Kress, Karl — UGB Countertop-Goyf

Hanson, George — Ad Nauseam

Laskin, Lewis — Dream Halls Combo

Bartan, Brad — Cascade Combo

Ahmad, Anwar — Zoo

Whitby, Damon — Ad Nauseam

Navickas, Justin — UGW Countertop-Goyf w/ Natural Order

Fishcler, Dan — Merfolk

stanco, Andrew — Zoo

Chojnacki, Robert — Zoo

Murray, Matt — Merfolk

Pike, Thomas — B/w Aggro (Deadguy Ale)

Benning, Mark — Bg Aggro

Gosse, Eric — Team America

Ho, David — Aggro Loam

Elias, Matthew — WBG Natural Order Rock

Shi, James — Canadian Threshold

Feder, Drew — Mon Red Painter Combo

Kuchler, Kevin — Elves Combo w/ Natural Order

Signorini, Daniel — Team America

Anderson, Lloyd — Goblins (mono red)

Lambert, Tom — Dreadtill

Kibe, Lance — Mono White Stax

Karmiche, Dominick — Dreadtill

Barnett, Michael — UW Aggro-Control

Roukas, Sam — Ad Nauseam

Spiecher, Richard — Goblins (R/g)

Miller, Daniel — Survival

Lambert, Robert — Dredge

Schulz, John — Mono White Control w/ Painter Combo

Lazzaro, John — B/G Aggro

Jones, Jesse — Goblins (Mono Red)

Moretz, Joseph — UGR Counterbalance-Goyf w/ Swan Combo

Mercer, Matt — Bitterblossom Control

Potucek, Josh — Landstill

Hinkle, Chas — Ug Merfolk

Bergeman, Ryan — Canadian Threshold

Thornburg, Robert — Egg Combo

Goetsch, Chad — Canadian Threshold

Sedgwick, Brandon — Dragon Stompy

Farrell, Michael — Goyf Sligh

Boccardi, Anthony — Dragon Stompy

Schoenacher, Anthony — Dredge

Bush, Don — 42 Land

Fontaine, Drew — Dredge

Harris, Visna — Transmute Helm Combo

Yosmanovich, Peter — 2 land belcher

Usary, Marsh — Zoo

Pereira, Adam — Dreadtill w/ Depths Combo

Getz, Justin — BGW Aggro

Mackay, Drew — Belcher Combo

Rozzero, Brian — UGW Aggro-Control

Resides, Jon — Merfolk

Gichan, Jake — UGW Painter Control

Bergeman, Phillip — Sligh

Gottschalk, Evan — Goblins (R/b)

Chen, Jeffery — Planeswalker Control

Crotty, Joseph — Mono-White Stax

DiMartino, Matt — Dreadtill

Gidosh, Nicholas — UGBW Countertop-Goyf

Nowakowski, Stephen — CounterTop-Goyf with Painter Combo

Sharp, Matthew — Stasis

Cavanaugh, Andrew — Enchantress

Krieger, Jesse — Ad Nauseam

McGirl, William — Survival

Buckner, Michale — Goblins

Devenines, Brandon — Zoo

McKay, Douglas — Wb Aggro

Lee, Shi Tian — Dredge

Folinas, Jefferey — UGR Countertop Goyf

Fortin, Mark — UW Control

Barnett, Michael — Dragon Stompy

Lapine, Michael — Merfolk

Earp, David — Mono Black

Bevenour, Matthew — Dreadtill

Leigh, Joe — UGB Countertop-Goyf

Dearolf, Chance — Elves!

Gearhart, David — Markov Control

Hernandez, Chris — Zoo

Soto, Hector — 83 card deck

Hale, Bryan — Affinity

Walk, Deven — Dredge

Ryan, Timothy — Mono Black

Thomas, Brian — Dreadtill

Langella, Nick — Bg Aggro

Orr, Jim — Affinity

Brantner, Drew — Mono Blue Faeries

Coss, Nick — BGW Aggro w/ Natural Order

Sanchez, Juan — Affinity

Milligan, Leigh — Cephalid Combo

Light, Jim — Mono Black

Ricker, Ahren — Scepter Control

Park, Andy — Survival w/ Natural Order

Metagame Breakdown

Here’s how that field broke down by archetype:

16 Counterbalance-Goyf

13 Zoo

9 Ad Nauseam

8 Canadian Threshold

8 Merfolk

7 Goblins

7 Dredge

6 Dreadtill

5 BGW Aggro

4 Bg Aggro

4 Dragon Stompy

4 Mono Black

3 Stax (Mono White)

3 Survival

3 Affinity

3 Belcher Combo

2 Team America

2 Landstill

2 Sligh

2 42 Land

2 Bitterblossom Control

2 Goyf Sligh

2 Elves!

1 Cephalid Combo

1 Scepter Control

1 UW Control

1 Enchantress

1 Stasis

1 Planeswalker Control

1 UGW Painter Control

1 UGW Aggro-Control

1 WB Aggro

1 Transmute Helm Combo

1 Dream Halls Combo

1 Egg Combo

1 Mono White Control w/ Painter Combo

1 Markov Control

1 Imperial Painter Combo

1 Aggro Loam

1 Bw Aggro

1 Cascade Combo

1 Counterbalance-Depths

1 B/g Hexmage Depths

1 Pox

1 Mono Blue Faeries

1 Stompy

1 Natural Order Rock

1 Life Combo

1 Terra-Goyf

1 UW Aggro Control

1 High Tide Combo

1 83 card deck

Before I begin analyzing the results, I want to compare it to the recent SCG Charlotte breakdown I did a month ago.

In Charlotte, Zoo was almost 13% of the field. In Philly, it fell to just under 9%. Counterbalance was an identical portion of the field in Charlotte, but, it too, fell down to 11% of the field in Philly. Merfolk saw the steepest decline of the major archetypes falling from 12% of the field in Charlotte to 5.5% of the field in Philly. What’s going on here? My guess is that Merfolk pilots saw the performance of Zoo and switched decks. At the same time, Ad Nauseam is now the third most popular archetype. Players saw the huge uptick in Zoo and switched to combo. Ad Nauseam Storm Combo (i.e. the Storm deck) went from 3.5% of the field to over 6% of the field in Philly.

Now let’s take a look at these archetypes distribution through the field.

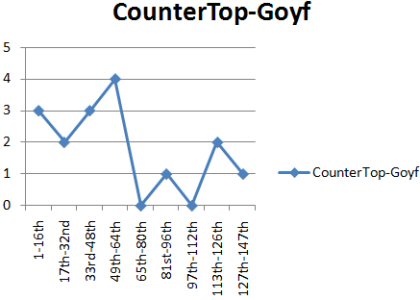

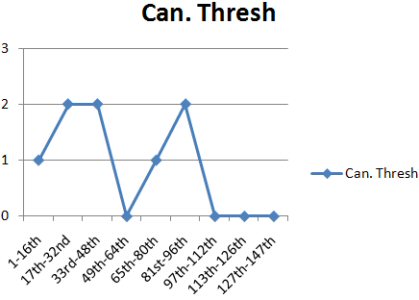

Let’s start with CounterTop-Goyf:

As you can see, Counter-Top was heavily weighted in the top half of the field, much like Zoo, as you will see in a moment. To some extent, this may be misleading because there were so many variations of the CounterTop Goyf deck. There was UGW, UGB, UGW with Natural Order, UGBW, UGRW with Natural Order, etc, etc.

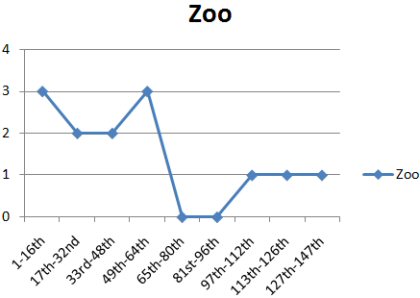

Now look at Zoo:

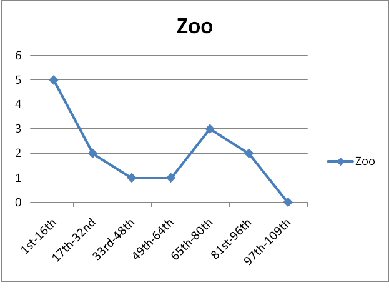

Now compare that to Zoo’s performance last time:

It’s clear that Zoo isn’t nearly as dominant this time.

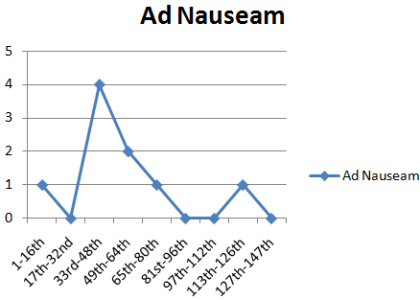

But what about the newcomer? What about the thought that switching to combo to combat the rise of Zoo and Goblins was the best strategy?

Wrong! Despite the prevalence of Zoo in the field, this deck did very poorly.

Canadian Threshold appears to be a perennial contender. Take a look at its distribution through the field:

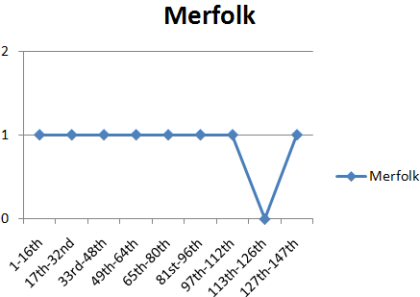

Now, let’s confirm our understanding of what’s happened to Merfolk:

Merfolk is almost perfectly distributed throughout the field. That’s remarkable.

Big Losers

It’s hard to tell what’s winning, since the Top 16 is such an even mix. However, we can tell you what’s not winning. Dragon Stompy, again, proved to be a poor choice. Dragon Stompy went 9-10. Affinity was another big loser, but with only two representatives, it went 0-4. Another big, big loser was Dreadtill, which went 10-12-2. It was even worse than Dragon Stompy.

Zendikar?

Zendikar definitely made an impact on Legacy, as players were using Zendikar Fetchlands everywhere. However, other Zendikar cards were also seeing play.

Here’s one of the more interesting decks I saw by Legacy celeb David Gearhart:

Spells (34)

- 1 Tendrils of Agony

- 4 Cabal Ritual

- 4 Hymn to Tourach

- 4 Dark Ritual

- 4 Bosium Strip

- 2 Skeletal Scrying

- 1 Mutilate

- 4 Innocent Blood

- 2 Tendrils of Corruption

- 4 Damnation

- 4 Beseech the Queen

Sideboard

Unfortunately, after beating the last place Survival deck, he apparently lost to Mono-White Stax and then Ad Nauseam combo in succession. However, according to the SCG records, David played one more round. Too bad for him, because he had the humiliation of losing to Goblins.

Hexmage has already made a splash. You’ve probably seen the Top 8 Hexmage-Depths combo deck. But I’m sure you haven’t seen these:

Creatures (8)

Lands (23)

Spells (30)

This player wasn’t content making 12/12! They wanted some 20/20 action as well! He beat Affinity and Mono Black Aggro, but lost to BG Aggro, Canadian Threshold, the Counterbalance mirror, and a Mono Black control deck before packing it in.

The more promising approach is this one, by Jonathan Bode.

Creatures (10)

Lands (23)

Spells (27)

Round 1: Zoo: Won 2-1

Round 2: Dream Halls Combo: Won 2-0

Round 3: Landstill: Won 1-0-1

Round 4: Canadian Threshold: Lost 0-2

Round 5: CounterTop-Goyf: Won 2-0

Round 6: Ad Nauseam: Loss 1-2

Round 7: High Tide Combo: Won 2-1

Round 8: CounterTop-Goyf: Lost 1-2

5-3 is not great, but at least he had a winning record.

What other Zendikar cards did I see in the decklists? Bloodghast, for sure. Spell Piece was scattered throughout. Cosi’s Trickster also saw play in some Merfolk lists. About half of the Goblins lists ran Warren Instigator.

Q: How Many Tarmgoyfs were Played?

A month ago I pointed out that 47.7% of the field in Charlotte had Tarmogoyfs, and 45% of the field in Boston. This time, only 43.5% of the field this time had 3 or more Tarmogoyfs maindeck, a 4% decline. Instead, there was a jump in Combo decks and decks trying to attack aggro strategies. By comparison, Force of Will appeared in 40% of decks. However, 9 of the top 16 decks ran Goyf.

Q: What Recently Unrestricted Cards Saw Play?

Dream Halls, Entomb, and Metalworker were all recently unbanned. Coming in at 57th place was this:

Creatures (1)

Lands (18)

Spells (41)

- 4 Brainstorm

- 2 Mystical Tutor

- 1 Duress

- 3 Meditate

- 4 Dark Ritual

- 4 Dream Halls

- 4 Serum Visions

- 3 Lim-Dul's Vault

- 4 Pact of Negation

- 2 Cryptic Command

- 4 Ponder

- 2 Cruel Ultimatum

- 4 Conflux

Sideboard

Round 1: Mono Blue Faeries: Won 2-1

Round 2: Dream Halls Combo: Loss 0-2

Round 3: Affinity: 2-0

Round 4: High Tide Combo: 0-2

Round 5: CounterTop-Goyf 1-2

Round 6: Canadian Threshold 2-0

Round 7: CounterTop Goyf: 1-2

Round 8: Mono-White Stax: 2-1

Lewis managed to win 4 matches with this deck. It appears that his win condition is Cruel Ultimatum, which he fires off multiple times with Nucklavee and Conflux. I didn’t see any Metalworker or Entomb in the entire tournament, which is too bad.

In the next couple of weeks I will be putting together a comprehensive Legacy Checklist, much as I did for Vintage. My list will be built around these decklists. Look for it.

Until next time…