“Let’s Start At the Beginning”

In my first column for StarCityGames.com, I chose to discuss the stages that occur in a Vintage game, a concept that many Vintage players misunderstand

and/or commonly overlook. In Michael Flores’ article

“Who’s the Beatdown?”

he states that “Misassignment of Role = Game Loss.” This principle is one of the governing statements of all Magic theory, and while it’s certainly true when applied to Vintage games, it’s often difficult to distinguish who is, in fact, the beatdown, which is apt to change not only from matchup to matchup, but from game to game, turn to turn, and even play to play.

In Vintage, role isn’t nearly as static as it is in other Constructed formats. Vintage games are often explosive and swingy, with players switching roles multiple times within a single game depending upon the context. A player’s understanding of how to navigate the quickly shifting landscape of a Vintage game is vital to playing the format at the highest level—since, every time a player doesn’t properly assess that they need to be changing roles, there’s a distinct possibly they could lose the game.

Vince Lombardi once stopped practice and addressed his team: “Let’s start at the beginning. This is a football. These are the yard markers. I am the coach. You are the players.” Some of the information in this article may seem fairly intuitive, but it’s always good to start at the beginning and get back to basics because I strongly believe that understanding these baseline principles are absolutely vital to strong Vintage tournament play.

Every single game follows a predictable progression from start to conclusion, and depending upon what stage of the game you’re in, a particular type of strategy and/or line of play will usually be preferable to another. For instance, in American football, a team has the ball on their own twenty-five yard line at the beginning of the first quarter, and it’s fourth down and eight to go—we know that most of the time the coach is going to punt; now imagine it’s the same scenario, fourth down and eight from the twenty-five yard line, but with a minute and a half to go left in the fourth quarter, with no time-outs left, and down by three points—in this situation we know that our imaginary coach must go for it because if the other team gets the ball back, the clock will run out, and the game will end. Such an analogy is purposefully constructed to demonstrate a circumstance where a line of play is obvious because it’s dictated by the context of a game state.

Most games of Magic: the Gathering aren’t won or lost because a player forgot to play a land on the first turn of the game, or played nine spells, had 2BB mana floating, and absentmindedly passed the turn without casting the Tendrils of Agony in his hand. The vast majority of games are decided by the lines of play that players take and the ways that their cards interact with their opponent’s throughout the middle of the game. There’s a lot more to being a good football coach than simply knowing you have to go for it on fourth down and long with a minute left, just like there’s a lot more to being a good Vintage player than knowing you need to cast Tendrils with nine storm and 2BB in the pool.

All Magic games have three distinct stages: the early game, midgame, and late/endgame.

The Stages of a Game of Magic

1.  Â

The Early Game

— is the first stage of the game where players try to accumulate the resources they will need to carry them through the midgame and into the late game. Characteristic moves of signature archetypes vary, but in general: “mana ramp” mages will try to generate the large quantities of mana they’ll need later to cast expensive spells; “aggressive” mages will put a threat onto the battlefield to make their combat steps advantageous; “combo” mages might tutor or manipulate their libraries to find a key card they’ll need to go off, and “prison” mages are likely to use the early turns to foil or undo the opponent’s early progress and attack his mana base. The key here is that in order to make it out of the early game, a player must complete whatever objective his or her deck’s early game requires first, before moving onto the midgame and/or endgame.

2.  Â

The Midgame

— after a player has secured the mana and other resources necessary to begin trying to win the game, he moves into the midgame, which is distinctly characterized by the battle between two decks where each is trying to execute its endgame. The midgame is when most of the action happens: players attack each other’s life totals with creatures, play spells which might generate card advantage or virtual card advantage, and jockey for superior board position.

3.  Â

The Late or Endgame

— occurs as the game begins to wind down, and one deck is pushing its advantage to the point where it’s trying to win the game. In the endgame, the aggro deck has created overwhelming leverage that will allow it to push through lethal damage via combat or direct damage, the control deck has neutralized its opponent’s threats and is attacking uncontested with a monster, and the combo deck is ready to go infinite and stop an opponent from disrupting its loop.

“Understanding and Identifying Role”

In Vintage, the stages of the game are often wildly compressed because of the power level of the cards that are commonly played. Consider the following: you’re on the play in game 1 with TPS against an unknown deck, and you have drawn the following hand:

Black Lotus

Lotus Petal

Dark Ritual

Dark Ritual

Mox Jet

Demonic Tutor

Duress

For those of you who may be tuning in from other formats, or just don’t see it right off the bat—this hand wins the game on the first turn through an opposing Force of Will. Play Jet and Duress opponent. Black Lotus, Lotus Petal, Dark Ritual twice, cast Demonic Tutor for Yawgmoth’s Will. Will, replay all of the fast mana, and Demonic Tutor for Tendrils with fifteen storm.

Notice that in this extreme example hand, the TPS deck is able to accelerate from the early game, through the midgame, and into the endgame all in the same turn. Since the hand has Black Lotus, Lotus Petal, and multiple Dark Rituals, there’s ample mana to do whatever it needs to do, which in this case is cast Demonic Tutor for Yawgmoth’s Will. The midgame here is basically whether or not the opponent has two free counterspells or started with Leyline of the Void in play, and the endgame is casting Yawgmoth’s Will and then recasting Demonic Tutor for Tendrils of Agony. Even though this hand wins on the first turn, before the opponent has even played a land, in order for the game to be won all three distinct stages of the game must still occur.

Now, what happens if we draw the same opening hand, and we’re on the draw against an unknown opponent? Let’s say that you do, and that your opponent is playing a Fish deck. On the opponent’s first turn, he plays Mox Ruby and taps it to play Sol Ring. He then plays a Tropical Island, casts Tarmogoyf, and plays Chalice of the Void for zero (which shuts off Black Lotus, Lotus Petal, and Mox Jet). The cards in your hand are now unable to produce a single mana.

You draw for the turn and add Tinker to your hand, have no play, and discard Lotus Petal. The Chalice of the Void has effectively negated this hand’s entire ability to generate mana, leaving you stuck in the early game, unable to advance to the midgame, until you draw a land. You’re stuck, at least for this turn, in the early game with no way to press forward.

On the opponent’s next turn he draws a card and seems quite pleased with it. He casts Tinker and gets “DAAAAAAARKSTEEEEEEL COLOSSUS!!!” He then attacks you with his 2/3 Tarmogoyf. Your life total drops to eighteen, and you’re staring down another thirteen points of damage at least next turn. Essentially, the opponent is curving through the stages of the game quite nicely; he has accelerated out fast mana, a threat, and a card to keep you stuck in the early game on the first turn. On the second turn, he was able to Tinker up a huge robot that will kill you in two swings and has moved into his endgame, which will be “Death by Darksteel.” None of this bothers you, of course, because you’ve still got outs and just need to draw…

A fetchland!

Obviously, the best possible draw. You crack Polluted Delta (seventeen life) and get a Swamp, because you have the sick read that he’s holding back Wasteland, (a read which is confirmed by the disgusted look on your opponent’s face, and cast Duress. He sighs and reveals his hand: Force of Will, Hurkyl’s Recall, and Wasteland (obviously). You snap-take Force of Will, and pass the action back to your opponent.

He draws, and quickly moves to his attack step, which is probably a good sign for you. You take fifteen damage (Tarmogoyf is now 4/5) and drop to two life. You’ve got several outs left, so hopefully the next draw step will give you something sweet, like…

Cabal Ritual!

Super lucky, because you know that if you cast Dark Ritual, Dark Ritual, Demonic Tutor for Yawgmoth’s Will, then get your three zero-cost artifacts countered by the Chalice of the Void, those cards combined with Duress and Polluted Delta in the bin gives you threshold for Cabal Ritual to cast Yawgmoth’s Will, which in turn lets you recast everything including Demonic Tutor for a lethal Tendrils.

However, you aren’t completely in the clear yet, because if your opponent has drawn Spell Pierce, Force of Will, or even Daze—literally anything that interacts with you—you won’t be able to execute your endgame. Here is the midgame: either you’ll be able to execute your endgame, or he’s going to stop you and kill you with his endgame, Darksteel Colossus.

You cross your fingers and run out Dark Ritual, and it resolves, as does every single spell you cast including a lethal Tendrils of Agony. Your opponent admits defeat and shows you that he drew a Flooded Strand, and you move on to the next game.

So, what can we take away from this rather contrived and scripted simulation game—besides that you live dangerously and caught some good luck?

The first and most important thing is that in Vintage, decks can move very quickly from early game into endgame. The abundance of fast artifact mana and powerful broken spells like Yawgmoth’s Will or Tinker enable players to breeze very quickly from the early stages of board development into the endgame and subsequent victory.

Secondly, we learned that some Vintage endgames are more efficient than others. In this example, the fictional opponent had a turn 2 11/11 indestructible trampler on the play, and it wasn’t good enough to win the game, even when backed up by a Chalice of the Void, which locked the opponent out of making any play on the first turn and a Force of Will!

Two of the most popular Vintage endgames, Tendrils of Agony and Time Vault + Voltaic Key, end the game immediately. These combinations are so efficient at locking up games that they make old Darksteel Colossus look like Tarpan.

The last and most important thing to be learned here is that if your opponent isn’t dead and hasn’t conceded, he probably has outs. A player must always be aware of what his opponent’s outs are and play around them as much as possible.

In this example, it didn’t seem like there was much the Fish player could really have done, as he got beat by your best possible draw steps. So, let’s complicate the scenario a little bit; after the game, your opponent says: “This is my first Vintage tournament, and I don’t really know what I’m doing—I didn’t think I could get killed like that after you had no plays on the first turn—I guess I should’ve Tinkered for Trinisphere!” (He’s obviously bad… he’s got Darksteel Colossus, so it’s theoretically possible he might also have had 3sphere in his deck.)

Any experienced Vintage player would obviously find such a mistake laughable, but it’s a mistake that people make all the time—perhaps, not on so severe a level as to not get Trinisphere against an opponent without land—but, it happens nonetheless. Â

The problem is that the opponent was making a line of play that didn’t consider his opposition’s outs, and was subsequently left vulnerable. Instead of locking his opponent in the early game with 3ball and applying slow pressure with Tarmogoyf, which is a strong line of play, the opponent instead opted to transition into his own less effective endgame. Remember the old mantra: “Misassignment of Role = Game Loss?” It’s true, and doubly true when your opponent is catching good cards.

In Vintage, the most important part of understanding your role is to understand how an opponent is trying to execute their game plan and to make sure that you have your bases covered so that this cannot and does not happen.

If the only way that your opponent can get back into the game is to resolve Time Vault, Yawgmoth’s Will, or Tinker/robot—it’s important that you do whatever you can from stopping these things from happening. In many instances in a Vintage game, the contextual advantages or “soft lock” a player creates over the opponent is good enough to win the game—so long as the opponent doesn’t have card X.

For instance, Stax might have the game wrapped up so long as the Tezzeret player doesn’t have Hurkyl’s Recall; or, a Fish player might have the game wrapped up so long as the control player doesn’t Tinker for Sphinx of the Steel Wind, or a control player might have lethal on board the next turn as long as the Storm deck doesn’t draw Yawgmoth’s Will.

In these situations it’s always important to cover your bases as best you can—sometimes a player is dead to a topdecked Yawgmoth’s Will or Tinker, which is fine so long as he or she did what they could to stop it.

A good example of this comes from years back when Meandeck Gifts ruled the Vintage landscape, and I played Control “Burning” Slaver. Suppose that I was playing exactly this matchup, Slaver against Gifts, and I arrived at a situation where my opponent and I fought a big counterspell war on his turn over Time Walk, and I won.

I’m empty-handed and get Mana Drain mana on my turn and topdeck Demonic Tutor. My board is five lands, a Mox, and a Welder, and my opponent has two mystery cards and an ample graveyard; let’s say Tinker is in the bin, too.

I can get whatever I want: I could Tinker, Mindslaver my opponent, and re-buy it with Welder; I could get Ancestral Recall and draw some cards; I could Sundering Titan away most of my opponent’s mana; but, all I ever wanted to do in this situation was Demonic Tutor for Tormod’s Crypt because I knew that Gifts was linear in the sense that it was probably only going to be able to beat me by casting Yawgmoth’s Will or Tinker—those were the two ways that they could win. If I have Welder in play, I don’t need to fear their Darksteel Colossus (this is before Inkwell of course) and with Crypt in play, I take Yawgmoth’s Will out of the equation.

The key here is to understand what your role is and not give the opponent an out, or even an inch.

I have another more current example of taking away an opponent’s outs. At Waterbury last month, I was playing game 2 of the Top 8 with Snake City Vault against a more traditional Tezzeret deck and was up a game. My opponent and I arrived at a situation where I had a six mana in play and was attacking for two with a Lotus Cobra. My opponent kept drawing and passing the turn without answering my Cobra, so presumably he was drawing blanks, probably permission spells. He also had eight mana in play. He was at four life as I drew for the turn and added Yawgmoth’s Will to my hand of Spell Pierce, Spell Pierce, Spell Pierce, and Misty Rainforest. I had Time Walk and Black Lotus in my graveyard. I attacked him down to two life and passed the turn without casting Yawgmoth’s Will for the game ending Time Walk. Why?

The reason is that clearly he didn’t yet have an answer to my Lotus Cobra. If he did have an answer, he would’ve used it by now. Literally no good could come from casting Yawgmoth’s Will here, as I couldn’t protect it from a counterspell with my Spell Pierces.

Even worse, if he had Mana Drain, there was the distinct possibility that he could have Inkwell Leviathan in his hand and that draining my Yawgmoth’s Will might actually allow him to win the game. Also, if he had Mana Drain for the Yawgmoth’s Will, he would get three colorless mana in his pre-combat main phase, which would turn off my Spell Pierces from stopping Key and Vault, or Tinker for Inkwell, etc. Playing Will here was more likely to help my opponent beat me in this context than it was to win me the game.

Also, if my opponent drew a ninth land and was forced to tap out for Inkwell, I could simply cast my Yawgmoth’s Will with triple Spell Pierce back up for another 2/1 and Time Walk for the win. He ended up bricking on the next turn, and I won the game, but my read was correct that he did have Mana Drains in the grip, and that there was no way that my Will would have resolved.

Once again, successful play always comes down to understanding what the role you need to take is based upon what stage of the game you’re in and what stage of the game your opponent is in.

On the draw with a Time Vault/Key deck, you fan out an opening hand of:

Force of Will

Tinker

Ancestral Recall

Dark Confidant

Polluted Delta

Island

Mana Crypt

The way that you play this hand is completely contextual and revolves around what your opponent is playing and what he or she does on the first turn. Suppose the opponent comes out of the gate with Mox Sapphire and Chalice of the Void for zero; what’s the play? We don’t know if they’re Fish or Stax—but, in either case the Chalice of the Void isn’t a game breaker because we have two lands and Ancestral and a Force of Will.

My instinct here would be to let it resolve, as there are much worse things that can happen if we burn the counterspell up front. If it’s a Fish deck and they Spell Pierce us, we’re in big trouble, or if it’s a Workshop deck, and they play a four-drop, we’re apt to fall behind.

The key here isn’t that plays are “right” or “wrong,” but rather that they’re contextual, and if we understand that role is a function of what stage of the game we’re in—it’s possible to make decisions that are sounder, and hence more likely to be good plays. Letting the Chalice resolve is also a nice play because the Chalice is likely to make the Tinker dead, which makes it an ideal card to pitch to Force of Will.

Once we’ve decided to let Chalice of the Void resolve, we must reevaluate what this decision means for how the game will play out, how it relates to our and our opponent’s roles, and how we move forward. It’s also significant that our opponent, at worst, only has four cards left to work with—whereas we have seven, eight once we enter our draw step, Ancestral Recall for good value, and a free counterspell with a card to pitch.

It’s also significant that our opponent has committed a card to the board, which is going to likely hold us in the early stages of the game for an extra turn or two—but, so long as we don’t allow them to either continue to bury us deeper and deeper in the early game, or advance too quickly into an endgame that we can’t properly defend against, we’ll be able to catch up and battle back.

The opponent plays Mishra’s Workshop (worst-case scenario), taps the Sapphire, and casts Lodestone Golem. Lodestone Golem is exactly the kind of card that we always want to counter against a MUD Deck, because it pulls double duty in the sense that it makes it difficult for most opponents to break out of the early game and into the midgame or late game. Also, once it starts attacking, it initiates the Workshop deck’s own endgame: death by robot beatdown. Lodestone Golem is no Tarpan…

People describe this phenomenon as tempo advantage, but what is “tempo?”

“Tempo Warp in Vintage”

Most Magic players think about tempo in terms of a situation where a specific play led to one player blowing another player out with a well-timed spell.

Player A has turn 2 Bitterblossom on the play, and on turn 3, he Spellstutter Sprites his opponent’s Kitchen Finks and then Peppersmokes his opponent’s Forge[/author]-Tender”]Burrenton [author name="Forge"]Forge[/author]-Tender. Tempo is a kill spell that makes you a free 1/1, but from an academic perspective, it’s most noticeably manifested in a play that moves you ahead while also putting the opponent behind.

In Vintage, players are allowed to play with cards like Yawgmoth’s Bargain, Necropotence, and Time Vault, where the idea of getting “value” in the form of a free 1/1 seems less than exciting (especially when you consider that Oath of Druids decks

give

away free 1/1s to anybody unfortunate enough to get them).

It isn’t that being up a card isn’t good in Vintage; it certainly is. Free stuff is always a nice, and any savvy player will always take whatever advantage they can get. Breaking out of a traditional soft lock is much easier to do in Vintage than in other formats because the combos are so powerful, and quite frankly, it isn’t very hard to put together a combination of cards that actually win the game.

Let’s revisit the Fairies scenario from a few paragraphs back. Player A’s opening is crushing the opposition, and it’s about to get worse because the Fae mage is going to untap, attack, play a land, and he has Cryptic Command in the grip.

What I didn’t tell you before was that now everything has changed, and now it’s a Vintage deck against the Block deck. The opponent plays a fourth land and casts Time Vault. The Faerie player attempts to Cryptic Command the Time Vault, but his opponent has Force of Will pitching Brainstorm. He then plays Voltaic Key, uses his last mana to untap Time Vault, and the game is over.

How much “tempo” does Yawgmoth’s Bargain provide? A card like Bargain has no tempo value because it simply ends the game, which is one of the defining characteristics that separates Vintage from other formats.

In the Vintage context, I like to think about tempo as the discrepancy between how quickly one player is approaching the execution of their endgame compared to his or her opponent; which is to say that “how strong a play is” relative to other plays is a function of how much closer it brings you to actually winning, or keeping your opponent from being able to win.

Unlike the Type One of the nineties where the biggest indicator of winning the game was how many times you had two-for-one’d your opponent, modern Vintage doesn’t necessarily care how many cards you’ve drawn, only that you finish him before he finishes you. Force of Will requires you to essentially two-for-one yourself to counter a spell for free and is the best tempo card in the format because it stops your opponent from winning, and it also stops your opponent from stopping you from winning.

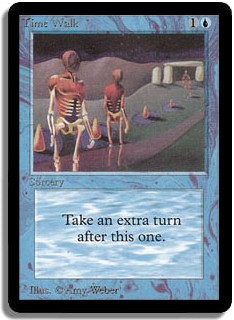

I used to play Vintage with Mark Biller (the guy who won the Timetwister painting) our lingo for “I pass the turn,” was actually “Am I dead?” Our other tremendous insight was our discovery that the player who resolved Time Walk the most times in a game almost always won. I miss the good old days when recurring Time Walk was honest:

Time Walk. Recoup, Time Walk. Burning Wish, Time Walk. Yawgmoth’s Will, Time Walk. Now it’s just called Time Vault. Sure it was filthy, but at least it was honest.

I refer to this phenomenon—of being able to just win the game from behind with an extremely powerful spell as “Tempo Warp”—because playing such a spell (Yawgmoth’s Will, Time Vault, Bargain, etc.) can essentially undo an opponent’s multiple turns of gaining incremental advantage.

Balance is the original “Tempo Warp” Type I card, as it allowed a player to get back into the game after being down two cards, two creatures, and two lands. No worries here: cast Balance and Wrath of God your team, Mind Twist your hand, and Armageddon all of your lands—and the backbreaker, I had three more Moxes in play than you did, so now I’m ahead.

The most common cards people play in Vintage that create “Tempo Warp” are Yawgmoth’s Will, Yawgmoth’s Bargain, Necropotence, Time Vault, Tinker, Balance, and Hurkyl’s Recall. All of these cards are examples of a card where one player can have achieved a large advantage previously in a game, but if their opponent resolves one of these cards, all of that advantage can be immediately undone. The game turns around, such that the opponent can now win.

My primary argument here is that in order to be an above average Vintage player, you must be able to, at every point in a game, understand where you stand and where your opponent stands; are you in the early game while they’re in the endgame? Are you in the midgame while they’re still in the early game? Once you’ve identified where you both are in relation to being able to win, you then need to identify what cards or progressions of cards are most likely to allow them to leapfrog the stages of the game to beat you, or which cards you need to undo the incremental advantages an opponent has already gained so that you can win.

Here’s an example of a game I watched a few weeks ago where a Workshop player did not utilize these strategies and was promptly killed in a game where he probably should’ve won against TPS.

The Workshop player had Lodestone Golem, Sphere of Resistance, Chalice of the Void for zero, Mishra’s Workshop, Mox Ruby, Mox Emerald, Rishadan Port, and Rishadan Port in play. The TPS player had Island, Swamp, and Sol Ring in play all untapped. It was the Workshop player’s turn and the TPS player was at ten. The Workshop player drew Smokestack, and attacked his opponent down to five. He then played Smokestack and left up Rishadan Port. He was dead, and he didn’t even know it.

The Workshop player should’ve been thinking about the principles I discussed in this article, particularly about stages of the game and “Tempo Warp.” If he had, he would’ve realized that he was close to executing his own endgame, and that his opponent was still locked in the early game; more importantly, he should’ve thought about what cards his opponent could possibly have to break out and win. The most likely way that the TPS player was going to be able to win was by casting Hurkyl’s Recall or Rebuild—and more than that, the fact that the TPS player had left up two lands and Sol Ring made it a pretty reason assumption that Hurkyl’s was the plan.

At the end of the turn, TPS Hurkyl’s Recalled the Workshop player and won the game on the following turn.

Here is where the Workshop player’s line of play breaks down. First of all, why did we even bother casting Smokestack? Lodestone Golem, if uncontested, would win the game next turn. If the Workshop player had realized how important resolving a Hurkyl’s or Rebuild was, he could’ve played around it to some extent.

Firstly, if the Workshop player tapped a Mox to Rishadan Port the TPS player’s Island in the pre-combat main phase, it would force the TPS player’s hand in making him either cast the Hurkyl’s Recall or not during his turn. If the TPS player cast Hurkyl’s Recall here, then the Workshop player could float a mana off the second Mox and replay his two Moxes, Chalice of the Void for zero, Lodestone Golem, and Sphere. This would turn the TPS player’s best, and possibly only relevant card, into prevent five damage, and little else.

It’s very unlikely that the TPS player would Hurkyl’s here, since he’s probably still going to lose, and he would probably try to Hurkyl’s on his upkeep to have one turn to try to win with no opposing artifacts in play. If TPS doesn’t Hurkyl’s in response to attacking, then Workshop still has a second Port in play to use during TPS’s upkeep to ensure he won’t be able to Rebuild during his first main phase after playing a land.

As it turns out, what ended up happening was that since the Hurkyl’s resolved at the end of turn, TPS was able to use all four of their mana during their following turn to play two Moxes and Time Twister, which found the win—but, even if it hadn’t, it would’ve shuffled all of the Workshop decks lock pieces back into his deck.

The key argument of this article is that in Vintage, the power level of the cards allows decks to move very fluidly from one stage of the game to another much more quickly than in any other format. In order to be successful, or perhaps to be “more” successful, understanding when these moves are taking place and reacting appropriately is often top priority and the difference between victory and defeat.

Identifying cards which will allow you or your opponent to “Tempo Warp” between stages of the game is imperative, as it allows you to play to your outs if you’re ahead or take away an opponent’s outs if you’re ahead.

If you know where you stand at every given point of every single turn, you’ll make better decisions, and perform better. Understanding how you’re going to break out of an opponent’s soft lock and win the game, and as important, understanding how your opponent is going to try to break out of your soft lock so you can stop them is the battle line that makes or breaks a close Vintage game.

Cheers,

Brian DeMars