Happy New Year, gamers! I hope that everybody has been enjoying the long stretch of Vintage Cube on Magic Online (MTGO). With the Cube undergoing so many long change logs as of late, there’s been plenty of new space to explore and more discourse around the best strategies for drafting the Cube.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the replies to this deck that I posted:

I don’t think that this deck is bad by any means, but in my mind, a 3-0 6-0 was a clear overperformance, and the deck felt like it leaned heavily on Mox Emerald and Sol Ring. A number of other players are more convinced of the ability of medium creatures and some interaction to convincingly close drafts, which has left me pondering the nature of our difference in philosophies. And so, today I want to talk about my philosophical approach to Vintage Cube and the concept of impossible games.

What Is an Impossible Game?

The Tweet-length description of this admittedly simple concept is that I want to draft decks in Vintage Cube that put my opponent in positions where they can’t ever win as quickly as possible. The deck above has some ability to do that some of the time, but I still have the expectation that one in three opponents should have a good shot at being better at doing so than this deck. There’s room for disagreement on this matter, but I’d like to take the time to break down my position here.

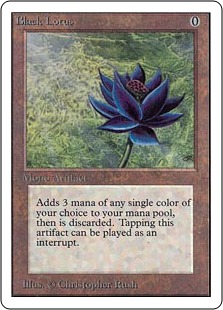

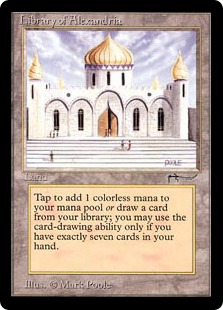

The question that I found myself asking that gets to the heart of the matter is, “What is the scariest turn in a game of Vintage Cube?” My short answer is the first turn. Your opponent can open on Black Lotus, some other means of deploying powerful threats well ahead of schedule like Entomb, a Strip Mine to impede your ability to play the game at all, or just a good old-fashioned Library of Alexandria to seal your fate one card at a time.

After that, the second-scariest turn of the game is whatever your opponent’s next turn is. More often than not, most of what’s scary about Turn 1 is comparably scary every time that your opponent untaps. Until you have won the game, this generally continues to be true. Having the right kind of interaction for whatever your opponent is getting up to can mitigate the scariness, but it’s really uncomfortable in my experience if your entire gameplan is to attack for three or four turns while your opponent draws from a stack of some of the most powerful cards ever printed.

With this perspective, you can see why I’m wary about the above deck’s ability to go 3-0. It has a lot of really powerful cards, but until the game is literally over, the deck has to sweat a lot of potentially broken things from the opponent over a lot of turns.

Of course, this is only meaningful if I can express what a deck that I have more confidence in looks like and explain why. The following build from the AlphaFrog run is a good example.

The lower curve gives the deck a faster clock, and the fast mana situation is similar, even if Sol Ring is clearly much better than City of Traitors. This deck also has Mother of Runes and Umezawa’s Jitte to invalidate more of what opposing aggressive decks bring to the table, and Library of Alexandria to embarrass anybody trying to win just by using removal spells or sweepers. This deck would love to have Solitude and Parallax Wave, but it’s set up in aggregate to sweat fewer cards and to win in fewer turns.

That’s enough about specific decks for now, and indeed it’s really easy to get lost in particulars when we just focus on examples. Let’s dive into the fundamental aspects of my philosophical understanding of Vintage Cube.

Proactively Generating Impossible Games

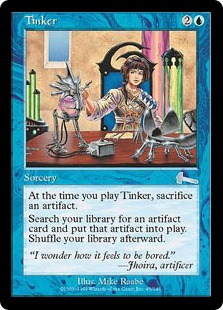

A trap that players can fall into is worrying too much about how they’re going to win the game, which results in going heavier on win conditions than important interaction and setup spells. Ultimately, however, you do need some way to close the game. In Vintage Cube, I put a high emphasis on drafting cards, even speculatively, that often put the opponent in an impossible position. Tinker is the poster child of this concept, as you can Tinker for a range of cards that put a range of different decks impossibly far behind. Cards like Upheaval or Tutors to find whichever of these cards fit your deck best also fit the bill.

Fast mana has a way of putting opponents impossibly far behind, which is why Sol Ring, Black Lotus, and even off-color Moxen are generally unpassable. Indeed, the Mox and the Sol Ring were fundamentally important cards for that first white deck I posted! That said, fast mana is only a part of the equation, especially in a deck that leaned on just attacking with a bunch of creatures. To the extent that it’s possible, you want to have some way to end the game before dealing lethal damage. This can happen through interaction, which I’ll get to in a minute, but it is more powerful to have proactive means.

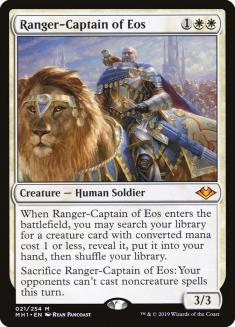

That first deck actually does have a form of lock which is worth drawing attention to. Guardian Scalelord looping Ranger-Captain of Eos will stop some combo decks from being able to win and will also lock out a lot of sweepers from controlling opponents. Being attached to a five-drop and relying on a specific additional card makes this lock somewhat difficult to pull off, but it fits the category.

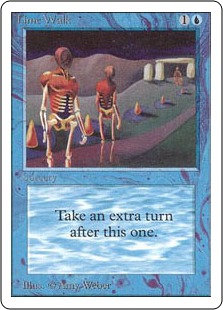

When I think of individual cards that lead to the most impossible games, the clearest example that comes to mind is Time Walk. I can’t say what the tipping point was, but for a long time, the average card was weak enough that card advantage generally just mattered more than battlefield presence. The opposite is true today, given the quality of threats available now. Being blue does mean that Time Walk can’t go into every deck that can leverage Black Lotus and Sol Ring, but now I believe that Time Walk is just the abstractly most powerful card in Vintage Cube.

Time Walk comes naturally with a lot of what a Mox offers by using it as sort of an “Explore”, but even that comparison is pretty disingenuous to early Time Walks given that if you cast it on turn two you do get to play a three drop right away. Then where Time Walk really excels is when you can take something like a two-turn clock and turn it into the game just actually being over. Time Walk’s existence more than doubles the scary things that can happen on any given turn from the opponent by vastly widening the range of ways that the game can just end. Including Time Walk improves every deck that can realistically cast it, and indeed the value of interaction in Vintage Cube is typically useful to the extent that it tries to emulate this exact effect.

Making Games Impossible Through Interaction

Matt Grenier is a name you’ll often see near the top of the leaderboard during Vintage Cube season. He is perhaps most famous for calling Endurance a Top 50 card in the MTGO Vintage Cube. It’s a really bold take, but it’s hard to argue against the fact that it’s working for Matt. Matt is one of a handful of Vintage Cubers who sees a lot of success by generally avoiding blue, a strategy that Caleb Durward also employed during his Cube for Charity streams last week. Some of their strategy revolves around cards like Gut, True Soul Zealot being undervalued by the player base at large, but the more fundamental aspect of the approach is that, if the opponent’s cards are so good, you can just destroy them.

Indeed, if you destroy your opponent’s win conditions and/or their means to cast them, they can’t win! Few decks in Vintage Cube can get by without playing any creatures, so you’re usually happy to have premium removal spells like Swords to Plowshares and Solitude, and the more all-in the opponent is on something like a Reanimate, the higher dividends these cards will pay. It’s also just really desirable to have some powerful artifacts in your Vintage Cube deck, and as such, artifact destruction naturally comes at something of a premium itself.

Grenier’s valuation of Endurance correctly identifies the graveyard as a zone that many of the decks trying to proactively generate impossible games exploit. Reanimator and Storm alike will often have a hard time setting up against graveyard hate, so it’s very consistent with my philosophy of “every turn is the scariest turn of the game” to pack graveyard hate as a way to insulate yourself against some of the scariest things that can happen. I’ve started to value Soul-Guide Lantern much higher in light of this, though an area where our philosophies differ is that I am much higher on counterspells as my means of interaction.

I don’t want to misrepresent Grenier and say that he doesn’t value counterspells. To be clear, his position, as I understand it, is that blue is worse-positioned than the Naya colors in recent iterations of the Cube. An aspect of this sentiment seems to be that the blue cards that you can get late are of lower average quality than the Naya cards that table. This can be because of the curation of the Cube list or just of the way players currently approach drafting, but whatever the reason, I personally see enough value over replacement in Counterspell to go out of my way to draft blue.

The long and short of it is that, all other things being equal, Counterspell is more likely to lead to an impossible game than any other removal spell, with Counterspell being an ace against those removal spells as the kicker. Counterspell isn’t on the level of Time Walk, but the same concepts apply. If the idea of using interaction is to stop my opponent from winning the game their way, then Counterspell covers a lot of bases all at the same time instead of requiring you to have a spread of other kinds of interaction and hoping that they line up correctly with your opponent.

My current hypothesis is that the best individual blue cards are so powerful that it’s worth going out of your way to play them, while still valuing interactive Naya cards highly. The following deck, drafted earlier this week, is a good illustration of the new philosophy that I’m trying to adapt:

This is ostensibly a Dimir control deck splashing white and red to stop any potential early creature onslaught, with Pyrokinesis being a massive overperformer relative to my previous expectations. The mana is a little strained to support Counterspell and Mana Drain, but those cards make it so that, as soon as this deck untaps with two mana up, the game is over. I’ll either be able to use my removal spells to clean up whatever you cast, or my Counterspells to get out of any especially sticky situations. Four- and five-color piles have been how many drafters approach Vintage Cube for a couple of years now, but this is the first time this sort of deck has really clicked for me.

I drafted Miscalculation over Cryptic Command for this deck, given that I knew I wanted cheaper interaction to facilitate my win conditions being a little on the expensive side. I did kind of think and hope that the Cryptic Command would wheel, though, as I do find that to be another of the most powerful cards in the Cube, and one generally undervalued due to costing triple blue. Four mana is a lot, but the more game state-agnostic your interaction, the better. As a counterspell that can also answer problematic permanents while drawing a card or throwing a Hail Mary to tap the opposing team, or to just win the game, Cryptic Command really just does it all and is on my short list of best cards to make the game impossible for the opponent through interaction.

One last note regarding Pyrokinesis and Endurance. These zero-mana forms of interaction are so far ahead of any other means of interaction for the same reason that all the fast mana is great. I’m sure that this isn’t new information for most readers, but this does stand out to me as an especially important aspect of generating impossible games through interaction. You can’t just tap out every turn to answer your opponent’s stuff, because until you establish your own position, they have the opportunity every turn to establish some haymaker that you can’t answer. Being able to interact for zero mana allows you to meaningfully turn the corner and put them on the back foot. For that reason, Solitude was absolutely one of the most significant cards in that first white deck that I posted.

Decks That Make Games Impossible for Themselves

Another aspect of impossible games that I want to touch on speaks to why a Naya deck full of creatures that attack and block is more appealing than trying to draft a Tinker or other cheaty deck. Any deck can draw the wrong number of lands, but only one trying to cheat giant creatures onto the battlefield can have a hand full of completely uncastable eight-mana spells.

In the pursuit of making the game impossible for the opponent, these decks sometimes produce tools that make games impossible for themselves. Don’t get me started on the embarrassing sorts of hands that Storm decks can produce…

It’s a valid takeaway, then, to simply avoid these archetypes that sometimes just can’t win, but in doing so, I believe that you’re closing yourself off to the actual most powerful decks in the Cube. Rather than steering entirely clear of Archon of Cruelty, I instead make a point to value cards like Currency Converter that let me clean up my hand and play a normal game, as well as other cheap haymakers like Jace, the Mind Sculptor to punish my opponent for focusing too much on interacting with the combo aspect of my deck. Take this Esper Control deck with a light Reanimator package, for example:

I’d have played a true Reanimate spell if I had one, but Shallow Grave on Griselbrand as a draw-seven is well worth the price of admission that helps this deck diversify its angles of attack. If you have the graveyard covered, then I have a perfectly good Sheoldred or Jace to get busy with. Meanwhile, I’m also pretty long on interaction of my own. Obviously, this is a luckier aspect of the deck, but the fact that Black Lotus and Sol Ring make Griselbrand somewhat castable is pretty nice, too. I’ll admit that there are aspects of this deck that are a little rough around the edges, but I do think it’s a good example of a deck with a combo finish that doesn’t go overboard and is great at just playing games of Magic otherwise.

The Hogaak Principle

Lastly, I want to state the most significant reason that I bias towards blue cards and win conditions that do more than attacking and blocking, a concept that has applied to many broken Constructed formats in Magic’s history, but one that I personally refer to as The Hogaak Principle, after Hogaak, Arisen Necropolis. The basic idea here is that the more broken deck has more wiggle room than the scrappy deck targeting it, and if the broken deck is allowed to adapt to beating the decks trying to beat it, it will.

My most significant tournament finish was when I made Top 4 at Grand Prix Minneapolis playing Mono-Red Prowess during Hogaak’s legality in Modern. I went 3-1 against Hogaak that weekend, losing to the ultimate winner of the tournament Justin Plocher in the semifinals. I drew the wrong number of lands in one of our sideboard games, which cost me the match, and I think Prowess was the right choice for me on that week, but there was in my mind no way for the deck to realistically see sustained success while the Hogaak deck remained legal.

Losing a close game because of the number of lands I drew might seem like just business as usual for Magic players, but this does highlight the way that Hogaak was by far the more broken deck in the matchup. If a Hogaak player ever complained about missing a land drop, it was either because they should have mulliganed or it was an incredibly rude thing for them to say while they attacked you for sixteen on Turn 3. Hogaak decks were just consistently powerful in ways that didn’t have to sweat all of the aspects of ABC Magic that an aggressive red deck does categorically.

I think the Hogaak deck was absolutely favored Game 1 on the play, and things were pretty even when Prowess was on the play by virtue of Crash Through and Lava Dart breaking through Narcomoeba in ways that other decks couldn’t, and the fact that you just mulliganed as if all of your opponents were Hogaak. The Hogaak deck had no reason to extend any such respect to Prowess, and that’s also why things felt generally favored post-sideboard. I brought in four Surgical Extractions and a Tormod’s Crypt, and they had some cards for me but no hammers. Imagine a world where they said they would rather just beat Prowess every time and brought in Chalice of the Void. Given time to adapt, the more broken deck will always become favored.

Now back to Cube. If it isn’t clear, I’m saying that blue decks with game-winning combos are Hogaak, and the Naya decks are Prowess. It’s true that the Naya decks can beat the combo decks with the right interaction at the right time, but the question on my mind is, what does that mean once everyone knows this is the new draft strategy? That’s what the Pyrokinesis is doing in the four-color deck I posted above. It’s acknowledging that you’ll likely have a plan for my Retrofitter Foundry, and then turning the question back on you with a Plague Wind for your win conditions.

I’ve started to value having some blockers a lot more highly in my blue decks to buy time until I can get a win condition to stick, and have had a lot of success against all of the Naya colors with this strategy. Sai, Master Thopterist has moved up furthest in my pick order in this regard, and I also draft the Thopter Foundry combo pretty highly now. All these cards are completely sick with Retrofitter Foundry, which I consider firmly in range for first-picking.

I used this deck to surgically dismantle a green deck in the finals of a draft:

My opponent cast three potentially backbreaking Naturalize effects against me in the deciding game, including a Tear Asunder on the Blightsteel Colossus that I Tinkered for! You’ve just gotta do something more powerful than Path to Exile my Hogaak, though. Having reasonably high access to blockers, few cards that could muck up my hands, and cards like Jace and Cryptic Command to turn to when the games weren’t easy was more than enough to close against even very hateful decks.

Now, I’m not saying that it’s easy to have a busted Tinker and Tolarian Academy deck with multiple plans and fallback plans like this masterpiece, but I am saying that I’m looking to draft decks like this when it’s possible, and I’ll take this over any Naya deck any day of the week. I’m learning to respect the Naya cards more, though, and I expect that decks like the four-color Pyrokinesis deck I posted will be closer to where I’m able to land in the average draft when everybody is fighting over both the good blue and Naya cards.

Dream Big

The general concept of impossible games was inspired by Jason Ford’s over ten year old article Dream Big, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t give him a shout-out. Rereading the article for the millionth time, it was delightful to read ruminations on how Cube metagames adapt in the piece. Seeing consistent success in Cube Draft will always be somewhat reliant on not just identifying the best things, but also on correctly identifying what other players are undervaluing and capitalizing on their assessments. You can’t go too wrong with Time Walk, but most drafts aren’t that easy, and every day, we can recalibrate and ask ourselves how we can go more right, and what we can do to more easily make games impossible for our opponents.