People often accuse me of being “loose” with my mulligan decisions. By some standards, they’re dead on. But this word—loose—has no meaning to me personally. In my mind, there’s no “loose” and “tight”; there are only good decisions and bad decisions.

Mulligans can be among the toughest choices we face in Magic. They’re made even more difficult by a prevailing mentality among players that good players mulligan a lot and weak players don’t mulligan enough. Any time you ask a group about a tough opening hand, you’ll invariably get more people answering “mulligan” than there are people who would actually mulligan when faced with the decision themselves. Nobody wants the stigma attached with advocating a “loose” keep.

When you keep a bad hand and lose, you can end up feeling like a fool. What’s worse is the fear of looking likea fool to anybody who knows about your dirty little secret. On the flip side, who would blame you after losing on a mulligan?

“I lost, but I mulliganed to five in game 3.”

“Poor guy! He played his heart out, but cruel fate stole his win away from him!”

We need to get over this! A win is a win and a loss is a loss. What other people will think of your decisions should not be a consideration as you’re making them. It may be true that weak players keep more than they should, but mulliganing too much is as real a problem as mulliganing too little! In my opinion, it’s a problem that afflicts many talented players. There are times when you should mulligan aggressively, but there are times when you should not.

It was the quarterfinals of Grand Prix Minneapolis. Benjamin “The Beast” Friedman, who was on the play with his U/W Delver deck, played a turn 1 Gitaxian Probe, and Brad Nelson plopped an infamous six-card hand, which you can see above, onto the table.

Spectators crowded in to get a closer look; phones and cameras set about recording the moment for posterity. By now, thousands of players have seen this no-land keep and had a good, hearty laugh at old Mr. Nelson’s expense. But not me.

This was a good keep. Not only would I keep that hand myself, but I feel that to mulligan would be a huge mistake. The way the two decks matched up, there was little Nelson could do in the early turns of the game which Friedman would be unable to answer. Given that Brad was going to have to win a “fair game,” a mulligan to five would have been a colossal—nearly insurmountable—disadvantage. This six-card hand has a reasonable, foreseeable route to victory (drawing an Island), while a mulligan to five does not.

Brad kept this hand and went on to win the game, the match, and make it all the way to the finals of the GP. He was “fortunate” that the lands he needed came off the top in a timely manner. However, the countless players who would have mulliganed would have had to get substantially more “fortunate” to win the game when starting with five (or four, or three, or two) cards in their hand.

Bravo Mr. Nelson, for making the best of a bad situation! Many other top players would have mulliganed and may not have come out of that match alive.

There’s a simple and important fact about Magic which deserves to be written down at least once: mulligans are bad. Starting the game with fewer cards dramatically decreases your chances of winning.

Whenever you’re faced with a bad opening hand, treat it as what it is: a bad situation. You have a choice between two bad options. However, you should never feel desperate or helpless. My goal in writing this is to help us all to make calm, reflective, honest decisions about our mulligans.

There’s a tendency to oversimplify mulligan decisions. With the millions and billions of possible opening hands we can face, it’s comforting to have bases of comparison and guidelines to help us. However, the reality is that no two hands are the same, just as no two players are the same and no two matchups are the same. Oversimplifying mulligan decisions is dangerous. In particular, I’d like to highlight two “false guidelines” that people incorrectly lean on.

“This card is already a mulligan.”

I hear this all the time. If someone doesn’t have the proper lands to cast a card in their opening hand, they may consider their seven-card hand as already having six cards and convince themselves that a mulligan is “free.” This is a bad attitude, except in extreme circumstances.

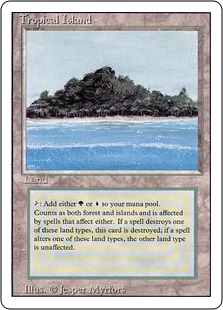

This hand has two white cards with no way to produce white mana. Nevertheless, I would keep it on the play or the draw. My plan is not to win the game with only blue mana; it’s to draw into white at some point (it need not be in the first four turns), cast my Geist of Saint Traft and my Restoration Angel, and win from there. The blue cards in my hand and on the top of my library can buy me time to do that.

Using the guideline of “this card is already a mulligan,” I would look at five cards: Island, Island, Vapor Snag, Mana Leak, and Snapcaster Mage with the option to trade those cards in for a random six. In that case, I would mulligan, which is why this guideline is misleading. It’s certainly not ideal to keep a hand with no white mana. However, the presence of the two white cards and the ability to draw into white mana and later cast them puts the decision over the edge in favor of keeping.

“You lose if you miss your land drop.”

Nobody likes missing land drops. I especially don’t like missing my third land drop or my second land drop. My guess is that Brad Nelson hates missing his first land drop just as much! But that doesn’t mean that he would have to concede the game as soon as it happens.

If you’re not facing imminent death, drawing out of a mana screw is a great place to be. It means you have a stocked hand! Sometimes your opponent simply doesn’t have an appropriate draw to punish you for missing land drops. Beyond that, though, when I’m faced with a land light opening hand I look for ways to buy time to draw out of a mana screw.

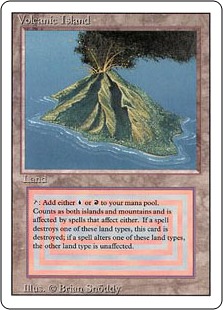

My educated guess is that many people would mulligan this hand no matter what because you can apply both of the above “false guidelines” to it. I would keep this on the draw as Grixis Control against an unknown opponent.

Applying the false guidelines, one would first argue that I have a significant chance of losing the game immediately. With 26 lands in the deck (25 remaining), I have a (28/53)(27/52)=27% chance of losing the game by missing my second land drop. I would counter by saying that I don’t automatically lose if I miss my turn 2 land drop. Maybe my opponent has a draw such that the Pillar of Flame really sets him back. Maybe I end up hitting Slagstorm mana at just the right time and make a great comeback.

Second, one might consider the Karn Liberated “already a mulligan.” After all, it costs seven mana and I only have one land in my hand. Grixis Control has to reach six or seven mana before it can win the game. That means that my plan is to drag the game out long enough to cast Karn. I will eventually be able to make use of him. In this particular example I also have Desperate Ravings, which gives my least valuable cards a chance of “cycling” whereas if I mulliganed to six I would also be choked on the resource of raw quantity of cards.

I call these “false guidelines” because they do not always hold, not because they are always wrong. Certainly there are matchups where missing a land drop is as good as losing. Certainly there are some situations where you can consider a card “already a mulligan.” One example would be having numerous finisher cards in the opening hand of your control deck. If you have three Grave Titans in your opening hand, the second one doesn’t look so great and the third one can probably be considered a mulligan (who needs to cast three Grave Titans to win!?).

Some decks contain cards which they do not actually want to draw. An aggressive Birthing Pod deck has little interest in having it’s one-of Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite in its hand. It’s actually a big problem for a Natural Order deck to have Progenitus in its opening hand! In that case, Progenitus can be worse than a mulligan, though this is further complicated by the presence of Brainstorm to “cycle” it.

So far, I’ve pointed out the dangers of mulliganing too much and of oversimplifying mulligan decisions. Such information, though, is not very useful unless we know what factors should influence our mulligan decisions.

How aggressively should you mulligan?

The reason there can be no all-encompassing guidelines for mulligan decisions is that they’re completely based on the context of the match. You cannot make an educated decision unless you understand the way your deck matches up against your opponents, the way the games are likely to play out, and what will be important in determining the winner of the game.

How important is card quantity?

Do you need to continue making land drops into the late game? If so, you should be less inclined to mulligan. Does the deck, or matchup, provide any way to “cycle” (make use of without casting) your weak cards? This could mean reshuffling them with Brainstorm, discarding them to Faithless Looting, pitching them to Force of Will, or any of the other uses there are for dead cards. If your opponent’s first turn play is likely to be, “Raven’s Crime you,” then you should be less inclined to mulligan.

What is your deck?

What is your deck’s game plan? For the Grixis Control deck in the example above, the plan is to trade a lot and use slow card draw spells to grind out small advantages over time. Voluntarily starting the game down cards is exactly contrary to this plan, so the pilot of such a deck should not mulligan aggressively.

On the other hand, take Boros Aggro in Innistrad Block Constructed. This is a deck whose advantage is speed. If you reach the late game at parity, Boros will be at a huge disadvantage because multiple of its cheap, efficient cards will trade for the Huntmasters of the Fells and Bonfire of the Damneds opposing decks are chocked with. In order to play to the strength of the deck you need to make sure you have a fast draw, so as a Boros pilot you should mulligan much more aggressively.

I chose Innistrad Block Boros as an example because it has yet another important factor playing into its mulligan decisions: a single card that has an abnormally large impact on the game. Because of the restricted card pool in Block, there can be a very large disparity in the power level of cards. Boros, for example, has a dramatically higher win percentage in the games where it starts with a Champion of the Parish than it does otherwise. You should recognize this and mulligan less frequently when you have a Champion and more frequently when you do not.

What is the matchup?

A more familiar situation for most people is postboard against extreme decks (Storm Combo, Dredge, Mono-Red Aggro). You’re likely to have single sideboard cards that dramatically increase your chances of winning if you draw them. Mulligan aggressively!

There may be matchups where you have to make adjustments to your game plan, and your mulligan decisions should change accordingly. Continuing with the same examples, Grixis Control cannot grind out G/R Beatdown the same way it does other decks. G/R is fast, brutal, and contains difficult to answer creatures and equipment to make sure that every single Birds of Paradise is a lethal threat. The Grixis gameplan needs to change; now the goal is not to drag the game out indefinitely but simply to survive long enough to cast a Grave Titan. It doesn’t matter how many cards are left in your hand after the Grave Titan, because the card is likely to win the game on its own. You can mulligan more aggressively because all that matters is having the Titan, the mana to cast it, and the tools to survive the early turns.

Now imagine you’re piloting the Boros Champion of the Parish deck against a mono-red deck that sports four Pillar of Flame, four Shock, and four Magma Spray. Now there’s little need to mulligan aggressively to a Champion of the Parish because the chances are low that it’ll survive anyway! What’s more, against a deck so focused on trading one-for-one against you, you certainly do not want to be down a card. In fact, this is the type of matchup where I would love to keep a land light hand to make sure I never run out of gas.

Is it Limited?

Under normal circumstances, you should not mulligan aggressively in Limited. Two well-built, well-balanced decks are likely to be relatively close in power level throughout the course of the game. There is always a lot of one-for-one trading, and in most cases there are not easy ways to make up card disadvantage. Therefore, being down a card is particularly painful. If there are cards that have an abnormally large impact on the game they are usually late-game one-ofs, so mulliganing to them is unnecessary or impossible.

Do you have faith in your deck?

The “faith in your deck” factor is one I learned from my cousin, Limited specialist Logan “Jaberwocki” Nettles. During long Magic Online sessions, I’d frequently message Logan for advice on tough hands:

“Should I keep this one lander on the draw?”

His reply would often be, “Well, how good is your deck?”

With a very bad Sealed deck, you may need to take some chances. The problems mentioned in the “Limited” section are more extreme, in particular the inability to make up card disadvantage. However, with an excellent deck you can feel more comfortable mulliganing because your chances of winning are very high even with a small disadvantage, so long as you don’t get screwed.

The same factor can be applied to Constructed, though it’s typically more related to the matchup (unless you’ve made a particularly great or terrible deck choice). In fact, Brad Nelson cited the fact that he had a bad matchup against Ben Friedman as one of his reasons for taking a chance on his no lander.

“… The version of Architect I was playing was very weak to Delver. That means I have to one-for-one you over and over and hope you flood out… A mulligan to five is a death sentence for this deck since I will not be able to do that with so few cards. I thought there was a better chance of drawing into one of my seventeen lands in the first two steps than getting a five even close to the power level of the six. I had to play very risky to win most games against Delver…”

Mulligan decisions depend completely on context: your deck and matchup. There are no unwavering rules about mulligans, so the only thing you can do is collect experience and consider carefully whenever you’re faced with a tough call. I’ll close with some examples and explain what I would do. Note that every example in this article has been chosen because it’s a close call.

Modern: RUG Delver vs. Hive Mind (on the draw)

This one actually came up today as I was taking a break from writing. Lightning Bolt is a fine card to draw into, but it doesn’t fill a critical role in my opening hand. Neither does a fourth land. I have no disruption, and although Serum Visions can help me find some, it’s not great at doing so. If I wait until turn 2 to cast it and stack the top of my deck with a counter, I may die on my opponent’s turn 3, defenseless. This matchup is likely to be over quickly and it’s not about attrition, so being down a card is not an insurmountable disadvantage.

Mulligan

Old Standard: Mythic vs. Unknown Opponent

Again, Mythic is not an attrition deck. The goal is to have one game-ending threat go unanswered. Your opponents will be dramatically less prepared for your threats if they come down quickly (if you have mana acceleration in your opening hand). Waiting until turn 3 to play your first creature will leave you vulnerable to permission, Oblivion Ring, Jace, the Mind Sculptor, and will generally mean being behind in the midgame where you need to be strongest.

Mulligan

Block Constructed: Boros vs. Unknown Opponent

This hand could provide a nice framework if you could draw into the right cards. However, Boros’ strength is in the early game, and since you only get a handful of draw steps in the early game you need to plan around what’s already in your opening hand. If your first play is a Midnight Haunting you’ll be on the back foot, and even if you topdeck Hellrider at the right time your opponent will have had leisure time to prepare for it.

Mulligan

Champion of the Parish is the best card in the deck by a significant margin, so I won’t easily give them up. This is the best possible hand if you draw into appropriate lands, and it’s still adequately aggressive even if you don’t hit your second land until turn 3 or 4.

Keep on either the play or the draw

Legacy: RUG Delver vs. Mono-Black Pox

There’s nothing that RUG Delver can do in the early turns which Pox will be unable to handle. Since RUG will have to win a fair game and Pox is a powerful resource denial deck, it’s absolutely devastating to start down a card. With this hand, Pox can miss with an Inquisition of Kozilek, which will suddenly give you an advantage in terms of card quantity. What’s more, there are plenty of ways to “cycle” dead cards in this matchup. If RUG draws into a Brainstorm, extra lands become useful. If Pox plays Hymn to Tourach, extra lands become useful. If Pox resolves Liliana (you’re in trouble, but) extra lands become useful.

Keep

The “Would You Keep This?” Game

The “Would You Keep This?” Game can be played individually or with a group, and it’s a good way to improve your mulligan skills both in general or with a particular deck.

Shuffle your deck, and then put seven cards on the table. Shout “Would You Keep This?” and then everybody answers the question. Set the hand aside, and repeat the process until you get through the whole deck. Don’t bother shuffling in between; the point is to see a lot of hands quickly! In a group, it’ll stimulate lots of helpful discussion. As an individual, you should put the hands into two piles: keep and mulligan, to get an idea of how often you’re mulliganing with your particular deck. You may learn that you’re being too aggressive with your mulligans, or you may learn that you should choose a different deck!

Normally, the “Would You Keep This?” Game is for on the play against an unknown opponent. However, feel free to try some exciting variations of the game including: “Would You Keep This Against Delver?”; “Would You Keep This Against Ben Friedman?”; and “Strip Would You Keep This?”