Today is my last article for Star City Games, so I figured I would do something slightly different, and continue a series that I started over ten years ago — my story with Magic.

- Part 1 talks about my start with the game, from the moment I first heard about Magic to my first professional-level event.

- Part 2 talks about my attempt to get on the gravy train and the years between playing a professional event and becoming a pro.

- Part 3 talks about my breakout year and how I ended up becoming a professional player.

Part 4 will talk about my life once I became a pro — how my life changed, how expectations changed, and how the way I approached the game changed. It will go from 2006 up to the point where my hand starts to hurt from all the typing.

With that said, let’s begin!

When last I left you, I had just played the 2006 World Championship, in Paris, where I lost to Makihito Mihara in the Top 8 in spectacular fashion. That result, alongside my earlier Top 8 in Charleston, catapulted me to Level 6, which was the highest Pro Club level one could attain at the time; in fact, it left me squarely in the Top 5 of the Player of the Year race, seemingly out of nowhere. This meant that, for the following year, I would have all expenses to tournaments paid — including flight and hotel — and I would also receive an appearance fee. So, from the span of one year, I went from basically a casual player to a professional player. I was no longer the person trying to get there; I was one of the best players in the world.

At that point, I was nineteen years old, and I wasn’t doing anything else with my life. I had started university (I was a physics major), but after one year of doing it I decided it wasn’t for me, and I decided to reapply to a different major the following year. The plan was originally to go back to university at the start of 2007, but I didn’t even know what I would want to do, so spending that year playing Magic suited me just fine, and with all expenses paid and extra money guaranteed on top of that, it was hard to say no. I always planned on going to university again (which I eventually did, graduating in International Relations some years later), but I wanted to have a better idea of what I wanted to do with my life first.

The first PT of 2007 was Geneva, and it was quite a change from my previous tournaments, because for the first time I was one of the “big players” — I had had a meteoric rise to the world of professional Magic, and people were eager to see if I was going to be able to follow up on that or if I had just had a lucky year.

I was also a polarizing figure; I felt like half the coverage staff loved me and the underdog story I represented, and the other half told their friends to watch out for me because I cheated. For some people, it was easier to believe that than to accept that this young kid from Brazil was suddenly winning everything. At certain points, I played against prominent players and then later on overheard them telling their friends that they were sure I had stacked their decks, for example.

I don’t believe the cheating stigma has ever truly left me. It’s certainly diminished, and I’ve converted a lot of my previous doubters over the years, but, to this day, I frequently receive random messages accusing me of cheating from people I’ve never even seen — comments on my videos, reply to my conversations, even the occasional Twitter DMs. In my Hall of Fame year, for example, I had what was basically a perfect resume and a writing career on top of that, yet I received only 70% of the player vote, and I know that at least some people did not vote for me because they thought I was a cheater.

The other people who didn’t vote for me likely just didn’t like me; when I was younger, I was very active in a lot of online communities and had an inkling for inserting myself in heated discussions and for telling other people when I thought they were wrong, which wasn’t always the nicest thing to do and certainly didn’t make me the most likable person to some.

Regardless of that, I entered PT Geneva as a person of interest; a lot of people were invested in my result, either hoping I’d win or hoping I’d crash and burn. Before the tournament, however, there was a ski trip organized by Wizards of the Coast (WotC), where I most definitely crashed and burned.

Before PT Geneva, I had never seen snow in my life, so when I got an email from WotC about a ski trip they were organizing, I was very excited. I really wanted to experience that for the first time, and I was also looking forward to socializing with my fellow players and inserting myself into this community; after all, I was going to be seeing these people frequently from now on and I wanted to make friends. None of the Brazilian players I was testing with wanted to go, and I don’t believe anyone else I knew was going either, but I didn’t let that deter me. One day before the Pro Tour, I was up bright and early in my ski gear, waiting for the bus that would take me and my newfound friends to The Alps.

Except that my “ski gear” wasn’t exactly ski gear — it was sweatpants, a regular jacket, and wool gloves. When we arrived at the resort someone asked me if I wanted to rent proper ski equipment, but at the time I did not have a lot of money (I didn’t even have a credit card) and Europe was expensive, so I was not about to spend this much on those “ski pants” when I had perfectly fine sweatpants right there, thank you very much. Of course, the first time I fell on the snow, which was immediately, I was soaked, and I spent the next couple of hours freezing to death through my clothes.

At the resort, we were split into two groups — beginner and advanced. I was obviously a beginner, and WotC had kindly arranged for an instructor for us. That would have been great, except I got lost from the party and couldn’t find them for a very long time, so I spent almost all of the trip on my own. I fell a lot of times, several of them trying to go up that ski lift thing, and eventually when I found my way back it was almost time to leave.

Despite all that, I enjoyed the experience and I enjoyed the snow — it was so incredibly beautiful. But it was an “I enjoyed this, but let’s not do it again anytime soon” sort of thing. As of today, I have never gone skiing again, though I kind of want to do it just so I know how different the real experience is.

The tournament itself went okay; it was Planar Chaos Draft. I ended up in the money, but just barely, which I guess didn’t make either my supporters or my detractors happy. To me, there were two big stories in this tournament:

The first one was that Willy Edel again made the Top 8. This made it three Pro Tours in a row if you didn’t count Worlds, and I think he got either T16 or T24 at Worlds in between those, which is just an absurd streak of finishes. However bad the cheating accusations were for me, they were twice as bad for him, and the fact that he kept putting up good results was very satisfying.

The second story was Kenji Tsumura. For a long time, Kenji was considered to be one of the best Constructed players in the world (if not the outright best), but he was famously horrible at Limited. At one point, he decided he was going to improve and become a good Limited player. He started talking to Limited superstar Rich Hoaen and to dedicate time to improving at it on his own, and that culminated with a Top 8 in an all-draft PT. Really goes to show you that dedication pays off.

2007 was different from 2006 in more than just the expectations around me — it was a completely different lifestyle. In 2006, I felt like Magic tournaments had been singular points in my life; in 2007, Magic tournaments were my life, a continuous line that never stopped. I quickly became an expert in traveling, airline miles, layovers, hotels, Expedia, and I bounced from place to place with nothing to anchor me home. Whereas in 2006 I had played one GP, in 2007 I played GPs in Montreal, Bangkok, Krakow, Daytona, Singapore, San Francisco, Amsterdam, Columbus, and maybe others that I don’t remember. I was a globetrotter through and through, and I often stayed with friends I had made online from all over. If there’s ever a PT in Porto Alegre, I’m going to need to rent a hotel to repay everyone’s hospitality.

After Geneva came PT Yokohama, and I was thrilled to have the chance to go to Japan again — it’s probably my favorite country (and at that time I did not even like sushi; now it’s my favorite food). This was Time Spiral Block Constructed, and Block Constructed was a format that I thoroughly enjoyed. We tested for a long time, and arrived at the conclusion that Mono-White Aggro was the best deck. Before flying to Japan, I spent a day in Rio at Willy’s house, and we played a Magic Online tournament with the deck. The Top 8 of the tournament was eight Mono-White Aggro decks, which was both very validating and very scary.

Creatures (28)

- 4 Soltari Priest

- 4 Icatian Javelineers

- 2 Cloudchaser Kestrel

- 4 Knight of the Holy Nimbus

- 4 Serra Avenger

- 4 Calciderm

- 3 Shade of Trokair

- 3 Stonecloaker

Lands (22)

Spells (10)

Sideboard

Whenever you have a deck to beat, you need to figure out if that deck is going to be hated out or if it’s going to remain the best deck even when everyone knows it’s the best deck. Decks like Temur Reclamation and Izzet Epiphany, for example, were clearly the deck to beat, yet they were still the best decks in their respective formats. Was Mono-White one of those decks?

We gambled that it was, and then we tweaked our deck for the mirror, but we were wrong. Everyone was trying to beat Mono-White, and everyone succeeded. In my very first game of the tournament, I was in a feature match (see, famous player now!) against a Mono-Red player, and my opening hand contained Soltari Priest + Griffin Guide, on the play, so I thought I was going to win for sure.

My opponent’s start? Turn 1 Gemstone Caverns + Blood Knight, Turn 2 Sulfur Elemental in response to my Griffin Guide.

Needless to say, everything went downhill from there. The entire tournament consisted of people casting Blood Knights, Sulfur Elementals, and even splashed-for Fortune Thieves against me. I got some wins, but they were not enough to make Day 2. For the first time in my life, I failed to cash a Pro Tour.

I was a bit sad about it, but I knew my streak couldn’t last forever. I had cashed my first nine Pro Tours, which was already way surpassing expectations, so I wasn’t too sad. Everyone on our team did badly and everyone playing Mono-White did badly, so I knew exactly what had caused our failure — we underestimated the lengths people would go to beat what they perceived was the best deck.

The rest of the year’s Pro Tours were not very successful either. Willy and I bricked the Two-Headed Giant PT (good riddance to that format, though), and I didn’t do well at the Valencia PT either. The Valencia PT was very interesting, as a flash flood hit the venue the day before the event, and Day 1 of the tournament ended up being canceled so that they could clean it up, so we played a two-day PT with a very long Day 1 and then played the rest of the Swiss + Top 8 on Sunday.

If the PTs weren’t successful, the GPs definitely were. I had multiple Top 8s and good finishes, which kept the dream alive for me to be a professional player the following year, even though my PTs had all been lackluster. One GP in particular was very important, and that was San Francisco. I was already friends with Luis Scott-Vargas (LSV) and the California crowd, but it was the first time we tested together. Luis, Paul Cheon, and I stayed at Web’s (David Ochoa’s) house and we practiced a lot, and managed to put three people in the Top 8 with our version of Mystical Teachings. It was also the first and only time I lost a game because I forgot to pay for a Pact. Oops.

The next big event was the Invitational, one of the coolest tournaments I’ve ever played. For those who don’t know, everyone at the Invitational submitted a card design, and the winner’s card ended up being printed (albeit with a couple of changes). This is where cards like Dark Confidant and Meddling Mage come from.

The format of the Invitational (and the qualification methods) had changed throughout the years, but in 2007 most of the invites (aside from a few fixed ones, such as Player of the Year) were voting-based, and there were categories such as Storyteller, Road Warrior, and Constructed Master, on top of regional slots. I had high hopes for the Latin American category, but Willy ended up beating me out for it by a couple of percentage points, and I was resigned to not play the Invitational that year. However, there was one final category I could still be a part of — the Fan Favorite.

I was hopeful, but realistically did not think I was going to get there, because I was just a kid from Brazil and I knew a lot of people didn’t like me, and this vote had basically everyone in it — twenty people were competing. What happened was very surprising. I not only won the vote, but I won it with triple the amount of votes that second place had, hitting 30% of the votes in a twenty-player field.

So, I qualified for the Invitational. It was to be held in Spiel, an enormous game convention in Essen, Germany. Here was the whole field:

The Invitational was super-cool, and it gave me the chance to do what I had hoped to do on the ski trip — interact with the other professional players. I played against all of these people in a very relaxed environment. I did spellslinging alongside Shota Yasooka, I had dinner with Kenji Tsumura, and I went bowling with Tiago Chan. If you’re wondering, Tiago bowled the same way he played Magic — very slowly.

This was the card I submitted:

Prolific Visionary (I wanted its initials to be PV)

1G

Human

Play with the top card of your library revealed. You may play lands from the top of your library as if they were in your hand.

2/2

This was two years before Oracle of Mul Daya was released, so I’m not sure if it was coincidence or if it served as inspiration to the card, but either way, I was happy that I had created a card that had an ability that was cool enough to see print.

The Invitational had five formats:

- Cube Draft. Same as now, two pods of eight players. The most interesting thing that happened to me was Gabriel Nassif trying to copy a legendary artifact, only to have it sent straight to the bin.

- Winston Draft. A 1v1 Draft format where there are three face-down piles, and then players look at piles one at a time and then decide to either pick them up or not. If you pick a pile, your turn to pick ends and it’s the other player’s turn (and then they do the same). If you don’t pick a pile, you add a face-down card to it and move to the next pile. And if you want none of the piles, you pick a new, face-down card from the stack. This is an extremely complicated and skill-intensive format, and it suffices to say I had no idea what I was doing.

- Build Your Own Block (or Make Your Own Standard). This format meant you could choose three sets to play cards from. Willy and I ended up playing an Enduring Renewal / Goblin Bombardment combo deck, which I believe is currently known as Fruity Pebbles.

- Auction of the People. This was the funniest format by far, and it consisted of people from home sending in decks with a theme. In this case, the theme was the alphabet, and every deck had to have one card with each letter (there were lots of Zuran Orbs around). Then, the players bid life and cards for each deck. The game started at 8 cards and 25 life, and then you’d bid down in line. For example, the auction on a certain deck would start, and a player would say “8 cards, 20 life;” another player would say “7 cards, 25 life;” and so on, and if you won you got that deck and started with those totals. Kenji Tsumura, for example, played a powerful Illusions / Donate deck, but that meant he had to start every game with only 5 cards! I played a five-color deck with a lot of Lightning Helixes, so I figured I could bid low on life rather than cards; I’m not sure what I ended up with, but I think 7 cards, 14 life at the end.

- Vintage. I had never played Vintage seriously before, and I owned no cards. Luis Scott-Vargas was a lifesaver and actually lent me an entire Vintage deck (the one with Gush and Fastbond). I was very thankful and honestly surprised; we were friends at the time but not as good friends as we became after, and the deck he lent me was worth many tens of thousands of dollars.

Card availability was a small problem, but not a huge one. I remember that Raphael Levy had a Berserk in his sideboard as a Cunning Wish target, but he didn’t want to buy a Berserk just for that, so he made a deal with a dealer — if he wanted to Wish for Berserk, he would run to the dealer, grab the Berserk, cast it, and then return it at the end of the game. We all wanted to win, but the Invitational being an unsanctioned event allowed for this kind of stuff.

I did very well at the Invitational. I believe I ended in third place (maybe fourth), but only the top two qualified for the finals, so I missed out. Tiago Chan won, and ended up making Snapcaster Mage (which had nothing to do with his original submission, a land that channeled for 2UU to counter a spell).

The next big tournament was Worlds in New York. Due to my good GP results, I arrived in New York within striking distance of what would become Level 7, which also gave you all plane tickets and an appearance fee (but no hotels). The format was Lorwyn Standard, Lorwyn Draft, and Legacy, and planeswalkers had just been released.

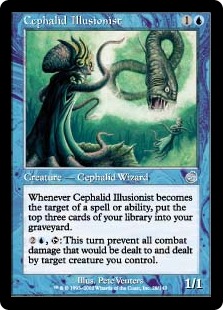

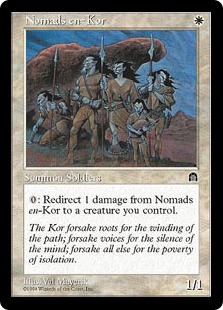

There are many ways to approach a new format, but one strategy that often works is selecting which new card is supposed to be busted — “the face of the set” — and then try to break it. For us, that was Garruk Wildspeaker. We thought Garruk was bonkers, and after several Garruk shells, we chose a Golgari-based aggro deck for Standard. In Legacy, I played Cephalid Breakfast, a combo deck that consisted in targeting your Cephalid Illusionist over and over with en-Kor creatures to mill your entire deck. I ended up doing reasonably well, and hit the required points for Level 7.

In the early rounds of this tournament, one of my teammates was sideboarding and pulled up a sideboard sheet with ins and outs. At the time, this was not legal (they were talking about it becoming legal, but it hadn’t been officialized yet). His punishment? A DQ! He was disqualified from the Pro Tour, a tournament he spent a lot of money and time qualifying for and flying to, because he had a sideboard guide. He wasn’t even trying to sneakingly look at it, either — he thought they were legal (and they did become legal shortly after), so he did it out in the open. A bit of a harsh punishment, if you ask me. After that, he decided to play the coolest side event there ever was in Magic — the “win a car” tournament. He ended up getting second, losing to Sam Black in the finals, who was piloting the most Sam Black deck you’ve ever seen, including four copies of Boggart Shenanigans.

Creatures (33)

- 4 Mogg Fanatic

- 4 Siege-Gang Commander

- 3 Greater Gargadon

- 4 Mogg War Marshal

- 4 Knucklebone Witch

- 2 Mad Auntie

- 4 Marsh Flitter

- 4 Mudbutton Torchrunner

- 4 Squeaking Pie Sneak

Lands (24)

Spells (3)

2007 was, overall, an uneventful year. It proved to me that I could compete at the highest echelons, that I wasn’t just a fluke, but also taught me that success was far from guaranteed. Previously, everything had been so easy; I don’t want to say it had been effortless, because I put in a lot of effort, but 2006 had made it seem that, as long as I dedicated, there would be rewards, and 2007 was an awakening to that mentality, because I dedicated just as much and did much worse. In the end, however, I managed to pull through the result I needed to continue my career as a Magic professional for yet another year, and it seemed University could wait a while longer.

2008 was a bit calmer than 2007. All the excitement from traveling died down a bit, and, being Level 7 instead of Level 8, my appearance fee for tournaments was smaller. Still I traveled a reasonable bit, and I finally got back to the Top 8 of the major events, playing the same deck both times.

The first PT was Kuala Lumpur, and it was the first time I stayed with Carlos and not Willy. I’m not sure why — it’s possible Willy just didn’t go to this tournament, having done worse in the previous year as well (I tried checking the standings to see if he was there, but obviously the WotC link is broken). The thing I remember most from this trip is going to an animal sanctuary, where we got to feed bears condensed milk:

The next big event was Hollywood, and that was the first time I played the deck that I became known for. Sometimes, players become associated with certain decks — Craig Wescoe with Mono-White, Sandydog with Mono-Red, Shaheen Soorani with control, etc. For a while, I was synonymous with Faeries.

Creatures (15)

Lands (25)

Spells (20)

Sideboard

For those who don’t know, Faeries was a Dimir deck that was fully in the middle of the aggro-control spectrum. The best comparisons would be Delver and Dimir Rogues in more recent years. It was a deck that I loved and that, eventually, I mastered. In my first PT with it, I was merely good with the deck, but over time I became great, and I used it to win Nationals, Top 8 a second PT, and T8 a handful of GPs, even when the deck wasn’t necessarily well-positioned.

In Magic, even among the pro players, there are players with vastly different strengths. Some are consistent, stoic, and never mess up. Others always pick the best decks. Still others have a way with bluffing and deceiving the opponent. My particular strength has always been the macro-game — understanding when I have to be defensive, when I have to be aggressive, and how I’m going to win the game. Faeries was a deck that rewarded that above all else, because it always gave you myriad options, and you needed to know what gameplan you were going to have.

With two PT Top 8s thanks to Faeries, 2008 was also a bit of a breeze, and by this point, I was fully established as one of the best players in the world.

As it almost always happens, though, all good things come to an end. I was a victim of my own success with the Faeries deck, and played it a bit longer than I should have. By the time PT Kyoto came, in 2009, the deck wasn’t a very good choice, but I decided to stick to my guns and play it anyway, because I played it so much better than I played anything else. It was not the right decision, and I was promptly punished by a very hostile environment. It was in this tournament that I decided to give sushi another chance and found out that I actually loved it, and what I didn’t like was the equivalent of gas station sushi I had had back home.

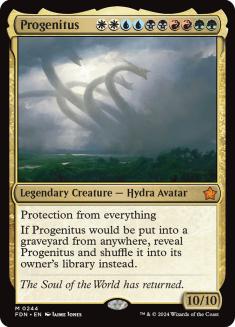

The next big tournament was PT Honolulu, and it marked the first time I did not test with the Brazilians. Instead, I tested with Luis and crew. The composition of Brazilian players had changed so much that I wasn’t friends with the qualified people anymore, and it felt more natural to play with the Americans, whom I was much closer to at that point. The tournament was hardly a success, with us playing some five-color deck that didn’t really beat anything, and half of us even tricking ourselves to play Progenitus as a legitimate win condition. That’s right, we couldn’t cheat it onto the battlefield in any way — we were just happy to pay WWUUBBRRGG for our 10/10.

Then came PT Austin, and for that tournament I went back to playing with the Brazilians, because two friends of mine qualified (I actually think the team was sort of a split team, but I remember talking to the Brazilians the most). Very early on we found out that we really liked the Vampire Hexmage and Dark Depths combo, and we never wavered from it, eventually building a version that I thought was very good. I made the Top 8 of that tournament, losing to Tsuyoshi Ikeda playing Zoo in a series of games where I felt particularly unlucky, though I had been pretty lucky in the tournament before. At one point, I had an opening hand on the play that would have made Stephen Speck jealous — Dark Depths, Vampire Hexmage, Chrome Mox, Chrome Mox, Black Card, Black Card. I made a 20/20 on Turn 1 and my opponent scooped without playing a land!

Worlds that year was in Rome, which turned out to be an incredible city. I tested with the Americans, and I was originally planning on staying with them throughout the tournament, but we found out the hard way that American hotels and European hotels do things a little differently. In the US, you pay for a room, and it doesn’t really matter how many people you put in it — and most rooms have two queen beds, so they fit four people. In Europe, you pay per person; if you get a room for two people, it really only fits those two people, and the hotel staff will be watching you like a hawk to make sure no one else sets foot in there. I ended up staying with some Brazilian players that I didn’t know very well but that had extra room in their Airbnb.

Worlds was, as always, a triple-format event, and one of the formats was Extended. I was back at the Airbnb trying to decide my last sideboard slot — Elspeth, Knight-Errant or Baneslayer Angel.

I wavered the cards in my hand back and forth and eventually settled on Baneslayer, at which point Potzz, one of my roommates, threw a fit. He said he expected us pro players to test everything, for us to have a methodology to determine which cards were good or bad, and there I was “just deciding,” with no information, no method, only luck to guide me. Potzz was very disappointed indeed, because in a short couple of seconds I had managed to dispel the entire illusion surrounding professional players. After that, Potzz and I became better friends and even played some team tournaments together. I think he’s probably the best Brazilian player that you’ve never heard of (his real name is Allison Abe).

Rome was also a special event because it was the first time I could bring my mother with me on a trip. If you’ve read Part 1 of this series, you know how instrumental she was in my Magic-playing history. Without her, I would certainly not have gotten close to where I am, so it felt great to be able to repay that in some way. Since then, she’s been to a couple more of those, and we always have a great time.

At the end of the year, I was again Level 7, enough for flights and appearance fees for all the events.

In 2010, something happened that would forever alter the landscape of professional MTG — Team ChannelFireball was formed. There had been teams before, of course — some extremely successful ones, like Kai Budde’s Phoenix Foundation or Darwin Kastle’s YMG — but ChannelFireball was the first superteam in modern Magic. We were about twenty people, from all over the world, and we spent weeks of dedicated testing at Luis’s parent’s house. ChannelFireball was not just a team but a store, and Luis asked if I wanted to write for them (I was already an established writer at that point, writing weekly for SCG). It just made sense to write for the website of the people I played with, so I decided to embark on this new journey and became a ChannelFireball writer.

Our first tournament was not successful for me, but it was successful for the rest of the team. We played Naya in PT San Diego, and it resulted in Luis’s legendary 16-0 run. I remember we arrived at the deck when we had a mock tournament and Tom Ross went 3-0 with the original version of it. The highlight of the deck was the sideboard combination of Cunning Sparkmage and Basilisk Collar (which you could tutor with Stoneforge Mystic), a combination that ironically we never played before registering but everyone instantly knew it would be great as soon as it was suggested (and it was).

For me, one interesting moment was when I was calmly chatting with a couple of friends between rounds and my name got called on my microphone. This was most unusual, so I worried about what had happened and went to find the judge station. It turned out that there was a Brazilian player (someone I had never seen before) who was having difficulty understanding that damage no longer went on the stack. They simply couldn’t explain it to him in English and they wanted me to translate the new rules. I did, he asked a couple of questions, and I translated back and forth. Afterwards, his opponent (who most certainly didn’t speak any Portuguese) accused me of giving him play advice in Portuguese in between the explanations. Cool.

We only put one person in the Top 8 of San Diego, but it wasn’t long before Team ChannelFireball dominated the professional field. In the very next tournament, in San Juan, we rented a beach house and put three people in the Top 8, myself included.

The format was again Block Constructed, this time Zendikar, and our deck was a very good Temur pile, though it wasn’t the best deck (that was Mono-Green). The Top 8, however, was Draft, and that highlighted the importance of having a team. I’ve always been a very good Constructed player, but I didn’t feel I was great at Draft; I wasn’t bad, but I didn’t have the ability to grasp a format as quickly as the best Limited players did back then (now, I feel that I do). Back then, we thought it was best to split our time, so I mostly focused on Constructed whereas some of the team focused on Limited (nowadays everyone does everything).

Rise of the Eldrazi was brand-new, and it was radically different from most other Limited formats in that mana ramp was king and cards that cost eight, nine and ten were routinely played (and very good). If you went to that tournament with only general Draft knowledge, your deck would have been nonfunctional because the format really had many particularities. And I personally couldn’t find those particularities, but my team did. Without a team, I’d have been lost. With a team, I followed the strategy they laid out (even when it didn’t make the most sense to me), and I won the tournament in fifteen long and tense games (every match in the T8 went the full five games; this actually happened to me twice more later on, in Kyoto and in Richmond).

Winning the PT was incredible, but not that much changed. I was already a very successful player (this was my sixth Top 8 in 23 Pro Tours), I was already living off Magic, and I was already a successful writer. So, even though it was an important milestone, my life didn’t meaningfully change.

One thing that did meaningfully change, however, was that I had finally gone back to University — I was an International Relations major. Even then, that didn’t impact my Magic life very much, because, compared to Physics (which I had previously studied), International Relations was laughably easy. I felt like I could skip class for two weeks, study on my own for a day, and ace a test. So, the only thing stopping me from getting my degree was my actual attendance. I spoke to all my professors, explained the situation, said it was my work, said I’d dedicate, and almost all of them were okay with it. For the following four-and-a-half years, I struck a balance between being a university student and a professional player.

Another big change was that I was finally being introduced to people who did not know the role Magic played in my life. My friends at that point were either Magic friends, or old friends who had seen me become a professional player, so they were used to it. My new university friends, on the other hand, had no clue about my Magic endeavors, so it was funny to see them slowly being introduced to it.

At one point early in the school year, I went away for a tournament over the weekend — one of those touch-and-go GPs that I thought I had to go to in order to get points. I skipped Friday and Monday, and I was back to school on Tuesday. One of my classmates asked if I had been sick; I said I had been traveling. He asked where to, and I said Canada. He didn’t believe me. Who goes to Canada for two days in the middle of the school year? It takes about twenty hours each way, so I almost spent more time in an airplane than in Canada!

When I tell people I’m a Magic professional, they often do not grasp the full extent of which I’m a Magic professional. At the same time, it’s hard to communicate it effectively without flat-out bragging about things — I’m not going to start listing my Magic accomplishments as I introduce myself. Just the other day, I had the following conversation with someone:

“[…] yeah, I play Magic professionally.”

“Oh, so you play in tournaments all over the country?”

“Actually, I play almost exclusively internationally.”

“So you’ve won some stuff domestically to get there?”

“Yeah, I guess I have.”

“You must be good then!”

“Yeah, I am.”

At this point, his girlfriend (who knew me) jumped in the conversation and said, “Honey, he was World Champion last year.” His eyes went wide. You could tell that was definitely not the scale he was thinking about.

Soon enough, however, my new friends got used to their classmate who was away half the year, as did most of the professors. I had to miss a few tournaments due to school (sometimes, for example, I’d just come back after one tournament, like that one in Canada, whereas in the previous years I would have just stayed abroad for an extra week to chain another tournament), but could still make every major competition.

After San Juan came PT Amsterdam and then Worlds in Chiba. For both these events, we had testing houses and our team did very well, putting multiple people in the Top 8. I was one of these people in Chiba, where we played Dimir Control in Standard and Five-Color Control in Extended. Dimir Control ended up being the best deck, and, after beating Jonathan Randle in the Top 8, I found myself facing Guillaume Matignon (my finals opponent in San Juan) in the Top 4 for very high stakes. If I won the match, I would be Player of the Year. If I lost the match, the Player of the Year would be either Matignon or Brad Nelson.

It was not to be, and Matignon got swift revenge from our previous meeting. It’s kinda unreal that, after winning a PT, getting third in another, and having an overall not-bad year aside from those, I still finished third in the Player of the Year race. Matignon and Brad ended up tied, and Brad would later win the title through a playoff in Paris.

The following Pro Tour, in Paris, was another very good one for Team ChannelFireball, as we created what might be the most famous deck in modern history — Caw-Blade.

Creatures (8)

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (26)

Spells (19)

- 3 Mana Leak

- 4 Day of Judgment

- 4 Spell Pierce

- 1 Deprive

- 4 Preordain

- 1 Stoic Rebuttal

- 1 Sylvok Lifestaff

- 1 Sword of Feast and Famine

Sideboard

Back in Chiba, most of our team played the Dimir Control deck, but some players did not — Brian Kibler and Brad Nelson played an Azorius Control deck with four copies of Squadron Hawk. That deck was named Caw-Go (derived from “Draw Go,” except with Birds – back when decks could have cool names instead of just being called [color combo] + [generic description] + [most important card in the deck].)

With the release of the new set, Stoneforge Mystic entered the scene, and it took the deck to a whole new level. Swords were added to the deck, and the name morphed into Caw-Blade. I did reasonably well, and as a team we crushed that tournament. The only reason we didn’t have more people in the Top 8 was that we kept getting paired versus each other in the later rounds.

This was also when the Player of the Year playoff match happened. The formats included Standard when our team happened to have the best deck of all time, and 10-Pack Sealed that was built the night before off-camera and was therefore impossible to understand or care about. I don’t know what the best format for a showcase match is, but I’m sure that built-off-camera 10-Pack Sealed isn’t it.

The next PT was Nagoya, but before that we went to Singapore for a GP. It was a very stacked tournament, because almost every pro did what we did (they traveled to Singapore before going to Nagoya), so it was a field of about 600 people where 200 of them were going to play the Pro Tour the following week. I again played Caw-Blade, and this time things worked out better for me — after playing about twelve mirror matches, I prevailed and got my first GP title.

Creatures (9)

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (26)

Spells (20)

- 4 Mana Leak

- 1 Divine Offering

- 2 Into the Roil

- 3 Spell Pierce

- 4 Preordain

- 1 Sword of Feast and Famine

- 1 Batterskull

- 1 Sword of War and Peace

- 3 Dismember

Sideboard

The thing I remember the most about this tournament, aside from my win, is Martin Juza’s Jace play. Martin was playing against a Gruul Valakut deck, and he used the [+2] on Jace, the Mind Sculptor, seeing Primeval Titan. Martin had Mana Leak in hand, so he left the Titan there, intending to just Mana Leak it. Once Martin passed the turn, he realized he had forgotten to play a land for the turn! This meant he didn’t have the mana to cast the Mana Leak, so his opponent just shrugged, cast his Titan, and won the game.

Can you imagine being Martin’s opponent in this spot? Your opponent has “Jace-locked” you, they look at your top card and leave it on top, so you defeatingly draw your card expecting it to be a basic land or something equally useless, and it’s actually the best card in your deck, which you immediately cast to win the game on the spot. Thanks, I guess?

For Nagoya, the format was again Block Constructed, and we found ourselves in a situation similar to Yokohama, where Tempered Steel (a white-based aggro deck) was clearly the best deck, everyone knew it was the best deck, and everyone was trying to beat it. We tried very hard to beat the deck, including maindecking a lot of artifact removal, and it still wasn’t enough. The biggest problem in that format was the mana — there was almost no fixing and Inkmoth Nexus was too strong not to play, so you were basically forced to be mono-colored, which really limited things.

In the end, we decided to just play Tempered Steel ourselves, because if we couldn’t beat it for the life of us, then we just had to hope other people couldn’t either (at least we were going to have a good version tuned for the mirror). It turned out that most people actually couldn’t beat it, though some people showed up with new decks that were clearly superior (such as the Puresteel Paladin deck that both David Sharfman and Pat Cox played). So, for that tournament, we managed to find the best deck that existed, but we missed out on the best deck that didn’t exist yet.

After that came PT Philadelphia, the first Modern tournament ever. Everyone was out there trying to kill on Turn 2, but we decided we were going to play it safe and just play Zoo with a blue splash for counterspells. It worked, kind of — I did not do very well, but Josh Utter-Leyton ended up getting second place.

Creatures (18)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (22)

Spells (18)

Sideboard

After that came Worlds, in San Francisco, and that tournament we also crushed. We played Tempered Steel in Standard and Zoo in Modern, and we put four people from our team in the Top 8, including myself.

2012 started very well for me. Being in University, I had to be conscious of how much time I spent away, so when the opportunity to go on a lengthy trip during our summer break (January-February) showed up, I took it. I planned a two-month trip that would take me to a Pro Tour (Hawaii) and several Grand Prix. The hope would be that I would acquire enough points in this one big trip that I wouldn’t need to fly to GPs for the remainder of the year.

The plan was a resounding success. I Top 4’ed GP Orlando, then got second at PT Dark Ascension in Hawaii (losing to Kibler in the finals in the Wolf Run Ramp mirror match), then Top 8’ed GP Baltimore right after. In fact, my trip was so successful that I cut it short — I had already acquired every point that I needed in the season and I wanted to go home. I did badly in the last PT of the season (Avacyn Restored, which Alexander Hayne won with Miracles, one of the worst decks to ever win a PT), but it didn’t matter as I was already locked for everything.

Spells (29)

Up to that point, since 2006, I had been Level 5 (eventually Level 7, eventually Platinum) or better every single year. This meant that I always had every single plane ticket paid and always got appearance fees to show up, which made it easy to be a professional player for these six years. The 2012-2013 season was when that was about to change, but not before we had the first Players Championship ever.

Before that season, the World Championship had always been another PT with a few particularities — it was always triple-format and had a team competition inside it. I really liked Worlds, as it was a lot more fun than a PT because you saw people from all over. After 2012-2013, they decided to split Worlds in two — the team competition became the World Magic Cup, and the individual portion became the Players Championship, which consisted of just sixteen players, the ones who had performed the best in the year before.

This tournament was fun as well. It was held at PAX West and was an interesting mix of serious and casual, as the stakes were enormously high but everyone was also good friends. We were playing for a lot of money, but we were also playing Cube Draft as one of the formats, so it reminded me a bit of the Invitational.

I didn’t have a good record at this tournament — I went 7-5 in the Swiss — but that turned out to be enough to make Top 4 (in fact, I was third in the Swiss). One of the particularities of these small tournaments is that, when someone runs the tables, everyone else meets in the middle, and that’s what happened. Shota Yasooka went 11-1 on his way to first seed, which meant that 7-5 was one of the best remaining records. The tournament cut to Top 4, and I played against second-seed Yuuya Watanabe. The matchup was pretty bad for me (I was playing Zoo again, and he was playing Jund) and he made short work of me.

In the end, I got my first “Top Finish” that wasn’t a PT with a 7-6 overall record that landed me in third place. It didn’t really feel like a “Top Finish.” but I’ll take it. Qualifying for that tournament was the hard part, after all.

The very first Pro Tour of the season was a special one, because it was my Hall of Fame induction, and I led a class of some serious heavyweights of the game — Kenji Tsumura, Patrick Chapin, and Masashi Oiso. My mom was also there, which made the moment pretty special for me. I remember that, when she got to the venue, BDM offered her coffee, and she accepted. Then she took a sip and almost spit it out — it was iced coffee. She had never had cold coffee before in her life — it’s just not a thing that we drink here in Brazil, and she was most definitely not expecting it.

The Hall of Fame ceremony was right before the PT started, so no one paid any attention to it as people were frantically scrambling to fill their last sideboard slots and sleeve their decks. Nowadays, the ceremony is held separately from the tournament, which is much better (or at least it was held separate from the tournament — nowadays there’s just no Hall of Fame anymore). Still, it was an incredible moment for me, seeing the video where my peers and the people who make the game recognize my accomplishments and my skills as both a player and a writer was an important moment of validation. Here’s the video, which I still watch about once a year:

The tournament didn’t go well, but that didn’t matter very much for me — that was the Hall of Fame moment. After the tournament was over, we had a fancy dinner with the WotC employees and the families of the inductees, and it was such a great moment. My mom didn’t speak any English and neither did the families of the Japanese players, but somehow they were talking as if they were old friends and managing to get their point across to each other. Kenji tried Brussels sprouts for the first time (he did not like them). My mom tried oysters for the first time (she did not like them either). I tried Kobe beef for the first time (I liked it). I was on cloud nine.

After that, it all went downhill. Through a series of bad decisions in both playing and deck selection (though mostly deck selection), I did not do well in any tournaments that season. I did not think I’d need to use my Hall of Fame benefits anytime soon, but if it weren’t for them, I would not have played every PT the following year, because I went from Platinum straight down to Silver.

My slump continued for yet another year, and I was Silver yet again. This was the nadir of my Magic career, and I didn’t know whether I’d be able to get out of it. I was depressed, unhappy, and for the first time ever I wondered if I was supposed to just quit and do something else with my life. I came dangerously close to doing that — in fact, I even interviewed for some more “normal” jobs before giving myself another year.

Ultimately, we know it all worked out. I eventually got back on top, and I’d say I even surpassed my previous accomplishments, but it was not an easy stretch of time for me, either personally or professionally. However, this article is already extremely long, and I would rather tell the story of those two years and how I eventually surpassed my slump in another installment, when I won’t have to rush through it.

If you’ve read through all of this, thank you for following me in this journey. I’m not sure what’s next for me in terms of content creation just yet, but I love writing and I plan on finding a way to continue doing it.

See you soon.