Do you know the saying “Game recognizes game?” It expresses the notion that those who are skilled in a certain area are more apt to recognize that skill in another. The reality is of course more nuanced than that, as the rise of analytics in sports has shown us, but there is a nugget of truth there. Along the path to expertise, there are common pitfalls that we all fall victim to, and after the fact, it is easy to see others falling into those pitfalls and thus gauge where they are along that path.

There are a lot of those pitfalls in a game as complex as Magic, from playing not to lose when behind to over-sideboarding out of fear, but one that doesn’t get as much coverage is the propensity to splash a color. Early in their development, Magic players are all too eager to splash and get another powerful card or two in their deck and are quick to dismiss the costs in doing so. On the other hand, top-level players are more conservative, opting to sacrifice some power to ensure their deck operates as smoothly as possible.

Count me in the camp that loathes to splash, so what I will be examining today is why this dichotomy exists, why splashing is something that should be done sparingly, and what factors go into determining when a splash is appropriate.

Do You Splash?

The first question is somewhat simple. It comes from how we are all introduced to the game and what attracts us to Magic. In those early days, lands and mana are little more than a means to an end. The fun part is casting our sweet spells and attacking with big creatures. Those are the cards that most often resonate from a flavor perspective, and so those are the cards that players are drawn to.

As a result, when building decks, the spells are paramount while the lands are afterthoughts. I’m sure you’ve had someone excitedly show you a new deck, only to see it end with the line “24 Lands” or the startlingly lazy “X Lands.” Sure, the manabase is there, but it’s a necessary evil, and it’s not as much a part of the deck as your planeswalkers, removal spells, and creatures.

Even worse, as new players gain experience, they learn to resent their lands as the primary source of variance in the game. Draw too few and you can’t cast your spells. Draw too many and you flame out in the late-game. No one is ever spell-screwed or spell-flooded. It’s always the fault of your lands. They just didn’t show up in the right quantity to give you a chance to play Magic. Stupid lands had one job and they couldn’t even do that right.

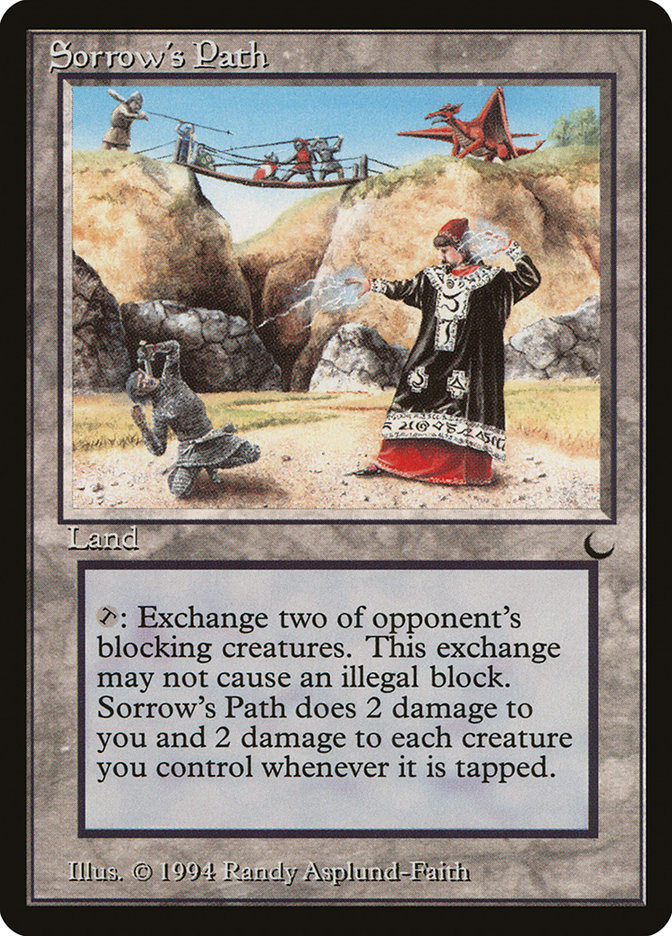

“I always lose when I have this card!”

Plenty of other trading card games have looked to “fix” the mana system from Magic so as to reduce variance, yet somehow none have managed to last. That’s because the mana system in Magic is a feature of the game, not a bug. Beyond the obvious justification that some amount of variance is needed to give worse players a chance and thus keep them interested, the mana system in Magic creates all the most interesting tensions in deckbuliding.

Finding the correct number of lands, the correct types to hit your color requirements, and trying to sneak in some utility lands as a mana sink are all real decisions that are not intuitive. In Magic’s early days, players were advised to build decks of twenty lands, twenty creatures, and twenty spells. Decks in the modern era play 23-26 lands unless they are very low-curved.

Proper deckbuilding requires that you respect your lands as an equally important part of the deck. The mana available in a format sets the bounds of what is possible by determining the price of the exchange between power and consistency. In multicolor blocks like Return to Ravnica, the exchange favors power because mana fixing is plentiful, whereas Kamigawa block had very little mana fixing, so the exchange favored consistency.

Determining how this exchange works in a format is paramount to understanding it, and while experienced players understand this, newer players tend to view the exchange as static. They are equally willing to splash regardless of the nature of the format, so long as they can play their sweet cards.

More generally, new players tend to underestimate the cost in consistency of adding some power to their deck. It is a result of viewing lands primarily as a source of variance. That viewpoint allows you to ignore the role your decisions played in the poor outcome. You were missing a color, how unlucky! But the reality is that, with only a few sources for your splash, there is a strong chance that you can’t cast the card after you draw it.

It is important to realize the role you play in the variance, both positive and negative, in your games. And that perspective tends to come with experience.

The Other Way

But this of course does not mean that better players never splash. They do it sparingly and under a few conditions. Let these be a guide for you the next time you are tempted to play a third or fourth color in your deck.

The first condition, a necessary one, is the presence of a card you even want to splash. Most cards, even powerful ones, are quite poor to add on a splash because it greatly limits the card’s effectiveness. On the splash, you cannot reliably cast the card on time. Threats want to be cast as early as possible so you can start attacking or activating the planeswalker. Creatures are sized closely to their casting cost, so their impact diminishes over time as larger creatures make their way onto the battlefield, so barring some other ability, waiting to cast one while you find your splash color is going to significantly weaken the card.

A good card to splash is one that fills a hole in your deck and is immediately impactful even late in the game. That’s a much narrower range of cards than you might first expect. Good removal spells are at the top of the list, along with powerful, expensive creatures. Maybe you want that extra flyer or just need a little late-game push. But beyond that, there really isn’t anything that is worth splashing.

In limited, a powerful two-drop like Voltaic Brawler or Veteran Motorist is powerful precisely because of its high impact on the early turns of the game. Their size and abilities make them relevant draws later in the game, but they don’t move the needle enough to justify a splash.

One thing I think most people overlook is that typical manabases in a Draft or Sealed deck are already weak relative to their Constructed counterparts. Having nine or ten sources of a color in a 40-card deck is typical for a main color, and that only equates to thirteen to fifteen sources in a 60-card deck, which is more typical of a support color. The goal should be to improve on the norm and attain a consistency advantage over other decks, not to exacerbate an existing problem.

In Constructed formats, the gains in power level are greater, but so are the downsides. Maybe a white splash in your G/B Delirium deck lets you upgrade Ob Nixilis Reignited to Sorin, Grim Nemesis and gives you access to a few different removal spells that are better in the metagame. Your deck is certainly more powerful and you’ll probably have the mana fixing to find your colors consistently, but any stumble, any extra lands entering the battlefield tapped, will be soundly punished by R/B Aggro and R/W Vehicles. So while you may not cost yourself much consistency in the abstract, that slight dip is punished more often in Constructed.

This calculus can change amid the presence of good mana fixing. We all remember the days of fetchlands and Battle lands allowing monstrosities like Four-Color Rally, Jeksai Black, and Mardu Green to exist, but I am thinking more along the lines of Attune with Aether and Traverse the Ulvenwald.

In decks built around Energy or delirium, these are solid enablers in even a two-color deck, but they also enable an easy splash should you desire one.

That is not to say that you should splash for the sake of splashing, but that having four mana fixers that you want to play anyway greatly reduces the opportunity cost of the splash. You should still only be splashing high-impact cards that are not timing-dependent or color-intensive. I don’t want to see Whirler Virtuoso in R/G Energy or Descend upon the Sinful in your G/B Delirium deck.

This whole splashing business gets to the heart of an issue I mentioned earlier: the dismissal of lands as a key part of deckbuilding. Mana is the engine that makes Magic run, and properly understanding and respecting that system is fundamental to understanding Magic. The first thing I do when breaking down a new format is look at the mana available and how that will constrain the format.

Take Those Rosy Glasses Off

The problem is that deckbuilding is at its heart an optimistic process. We scribble down 60-75 cards while only imagining the times when everything comes together and our opponent is left helpless. We like to think of deckbuilding as an arena with limitless possibilities where anything is possible. We want to push the limits of what is possible and explore space that is new and exciting.

Mana is the fun police in all of this. It’s there to rein us in and keep us grounded. Initially that role makes mana appear cruel, as deck after deck is discarded when in testing it is shown to fold to itself or to token resistance from the opponent. And eventually we all reach the point where we just want to play with the toys we like in the way we like to play with them, mana be damned.

But the reality is that the restrictions that the mana system places on deckbuilding are what make the game interesting. After all, restriction breeds creativity. If you could just play any card you wanted, then only the best cards would see play and Magic would ultimately be boring. The most powerful cards need a check placed on them or they would be oppressive.

The mana system is that check. It’s like the salary cap in professional sports. Without it the biggest markets would outspend the smaller ones by such a margin that they could establish a dynasty. Then we’d basically have soccer, and this is America; we hate soccer. And we love rooting for the little guy. The mana system allows the little guy a chance, since you can beat them by being fast and consistent, even if you’re underpowered.

So do yourself a favor and learn to embrace the mana system in Magic. Sure, sometimes you keep a three-lander and never find a fourth or you get into a topdeck war and draw six straight lands. Those are frustrating but necessary for the game to function properly.

Splashing is a last resort for a deck that didn’t quite come together. Learn to treat it as such and you just might find that the mana gods aren’t quite as fickle as you thought.