Yea, anyone who plays a lot of Magic tournaments knows that’s great theory that tends to break down in practice. Maybe it’s early in a format and new decks pop up days before a relevant event and you quickly learn you really have to change what you’re playing. Or you know a deck, and on Sunday the metagame shifts to its worst matchup being the deck to beat for the next week. Or maybe you’re just jumping back into Historic after a while off and the deck you know is just bad now and you need something functional for Saturday.

This is especially true with the structure of the current SCG Tour Online $5K Championship Qualifiers. Maybe you chose right the first time, crushed a Satellite with a deck you love, and Sunday rolls around and you change nothing. But just as often I find myself going 4-2 to lock in a qualification, not loving my choice, and wondering if I should switch to one of the breakout decks from the Satellites without a ton of time to decide.

Or maybe you just got an adorable new puppy and are too busy bragging about him on the internet to play a ton of games. Who knows. That could happen to anyone.

Fortunately, if you’re deciding to play a completely new deck with little time to play dozens of matches with it, there’s a process you can follow to maximize the time you do have. Let’s take a look at this challenge through the lens of how I approached the Four-Color Blink (Yorion) deck I picked up a couple of weeks ago for the most recent Standard $5K Qualifier.

Creatures (7)

Lands (34)

Spells (39)

Step 1: Copy Existing Work

The first step in quickly getting up to speed on a new deck is letting other people do as much work for you as possible. Remember, it’s only plagiarism if you don’t cite your sources.

Me just saying this is useless, because the place everyone starts is looking for someone who made a list and sideboard guide for you. The useful thing I can talk about is how to utilize each type of info you could find.

If you’re looking at a sideboard guide, the important information is usually the stuff between the decklists and the pictures of what to sideboard in and out in each matchup. Look for the notes on what matters in each matchup, the mulligan decisions, and common lines of play. You can easily sideboard properly for a matchup and get destroyed because you don’t know what matters in the games, or the best sideboard guide out there could be for a list that’s three weeks old and ten cards different. The later was certainly the case with the Four-Color Blink (Yorion) deck when I picked it up. If you know what matters in the games, you can probably derive a good enough sideboard plan without even seeing a guide.

You might notice I go out of my way to include these in all my deck guides, and the next few steps will be the best ways to fill in these blanks. If the person writing a deck guide does everything right, most or all of this should be information you can transfer in a few pages of text, and I spent years getting this information from people in the late stages of Pro Tour testing. That “should” is of course gated by a lot of stuff, and even the best guide is going to either miss something the author didn’t think to include or didn’t know how to phrase well, or that the reader missed because including everything makes the guide a 10,000-word infodump.

If you just have a decklist and a sideboard guide without any of the context, that’s a fine start, but you should really be approaching everything with three assumptions: everything you have is more likely to be wrong, you’ll have to figure out why each plan and card choice could be right, and it’ll take more time to sort that all out.

With Four-Color Blink (Yorion), the baseline research was pretty easy. The February Kaldheim MPL and Rivals League Weekend happened just before that $5K Qualifier, and three players played Four-Color Blink (Yorion) and streamed it to Twitch: Andrea Mengucci, Kenta Harane, and Yoshihiko Ikawa. If you’re interested, you can currently view the VODs of that weekend for at least a little longer.

What is the best way to use a Twitch VOD? Scraping the sideboard plans of players is pretty easy, and you can watch it at 2x speed. Even if you aren’t playing matches at the same time, and even if the VOD is on mute or in a language you don’t understand, that’s twice as much “gameplay experience” you get in the same amount of time. League Weekend VODs have a super-nice feature of all the matchups being recorded, so if you’re in a hurry to specifically see how all the best players play against Mono-Red Aggro❄, you can find all the times they played that matchup, what rounds, and just go.

Step 2: Reverse Engineer Winning Plays

At my very first Pro Tour back in 2009, I played Faeries after having played less than ten matches with it before that event and Top 16’ed. I then played two or three more events with it before Top 8ing a Grand Prix with it a couple of months later. The key to skipping all the hard work: I had just lost enough to Faeries while playing everything else to know what happened in the games it won.

Make the plays that people who beat you with the deck make. Easy.

If you’ve played the format of the event you’re diving into, you’ve probably played against the deck you’re swapping to. You probably have even lost to it. What actually happened in the games they won? Magic players are really good at remembering the games that went uniquely badly for them. When you feel like you have a solid hand and your opponent just embarrasses you every turn of the game, you definitely remember it. Just take that loss and try to give that experience to someone else.

If you haven’t played the format, that’s where you can hit the Twitch VODs. Layering on the previous advice, notice the games where the streamer’s opponent takes reasonable game actions and just dies, and then try to replicate those. Sometimes you don’t have a lot of agency there, like how “cast three one-drop creatures by Turn 2” isn’t really something you can do a lot to control when playing Modern Burn, but often you do.

When copying Tian Fa Mun’s list, I had a huge edge here. I had played a lot of Gruul Adventures and was well versed in how losing to Doom Foretold decks worked. I literally lost to Tian Fa Mun playing then-Esper Blink (Yorion) in the finals of a $5K Qualifier in Zendikar Rising Standard. Really aim for Turn 5 or Turn 6 casting Yorion, Sky Nomad and getting on-battlefield value off the trigger, often using Turn 3 to pick up Yorion, Turn 4 to cast Binding the Old Gods, and Turn 5 getting to use Yorion as a Shriekmaw plus some.

I had also lost to Yorion decks with Mono-Red Aggro a lot over previous formats. The games that go wrong involved the Yorion side getting off a good Omen of the Sun early, or bridging early removal into a value Yorion and pulling out a narrow margin of victory.

I did do one thing imperfectly: using assumptions based on previous iterations of the same format is a dangerous game to play. Fortunately Throne of Eldraine remains so stupidly broken that very little about the general patterns of Standard has changed for a long time, but I easily could have been burned if accounting for Alrund’s Epiphany out of Temur Adventures was functionally different from dealing with something like Questing Beast.

Step 3: Categorize Matchups by What Matters

I may have jumped the gun on the “all the one-drops as quickly as possible” example, because in the London Mulligan + open decklists era of events you often have a lot of control over how the start of every game will line up.

Once you’ve put some thought into what the winning lines are in every matchup, try to categorize them into ones where you need something specific to happen, like casting a hate card or having a removal spell at a specific point, and ones where you can generally just play Magic with a wide variety of cards.

Then step back into that “replicating game-winning setups” mind set and do that from Turn 0 of every game.

If you’re playing games, I like to start by assuming I can just play Magic and then adjust if it becomes clear I can’t. It’s way easier to figure out what specific thing you need to do to win if you start with, “Well, I’m losing with the general plan of casting spells; what went wrong?” rather than picking the right plan to focus on from thin air.

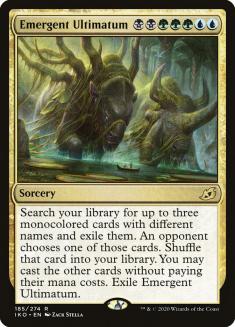

A case of this actually panning out occurred when I was testing the Sultai Ramp (Yorion) matchup with Four-Color Blink (Yorion). To get the main issue out of the way, the matchup is just bad for the Four-Color side. Your opponent has literal seven-mana-win-the-game, and you don’t. You would assume that you need to mulligan to find an answer to Ultimatum and a hand that generally fights control battles, but in practice that wasn’t the case. Emergent Ultimatum is a late cast, and you can often just find your way into the Negate by the time they find and cast Ultimatum.

On the flip side, your resource count really matters: removal randomly finds targets like Esika’s Chariot, your opponent isn’t just Ultimatum or bust so you have to fight against their Yorion, and all your lands matter in these fights and the eventual game state where you need to move towards killing them while leaving up Negate. You don’t keep hands that are three lands and four removal, but a few lands with an Omen of the Sea and a couple of other spells is good enough.

Better than any other step, this one showcases that you’re trying to generate actionable info. Whether a matchup is good or bad certainly can define deckbuilding decisions or deck selections, but once you lock in a deck for an event, the question is always, “What is my plan to win this match?” If you’re trying to get competent with a deck in short order, that must be your focus. I know I usually won’t beat Sultai Ramp (Yorion) with Four-Color Blink (Yorion), but what does it look like when I do win the games?

Step 4: Test for Common Scenarios

After the first three steps to establish a general approach to each matchup, we’ve reached the part where you need to sit down, play matches, and figure out the smaller details. Like I mentioned at the start, even the tips and tricks in the best deck guide will miss something that’s obvious to the writer and not to the reader.

For example, maybe you’re someone who values cycling Triomes more than the writer of a deck guide does. You hold back the Triomes if you draw them after Turn 3, but it turns out on Turn 6 of a matchup you really need double blue and it’s hard to get to that point without playing Zagoth Triome every time you have one in hand before then.

The person writing who only cycles Triomes if they topdeck them super-late might never see that issue pop up, and they might just not even think about how it could pop up because their mana just looks different every game. With both Triomes and Pathways in Standard this type of hidden pitfall is going to be everywhere, and until you screw it up and lose you probably won’t notice.

Or the even worse pitfall: everything you assumed about a matchup only applied last week, to players with an old plan and an old sideboard. If you play against Brad Nelson in your next event at 3-0, what is your plan?

These pitfalls are often matchup-dependent, which is why you need to start at the top. Get the most repetitions in you can against players with top-tier decks, who have up-to-date lists, and who are trying to do things right.

While the absolute best way to do this would be ping people you know who play each of the best decks, have their list ready for that weekend, and play against them, that just isn’t practical or necessarily optimal. Ignore the “scheduling” and “having that many friends” parts, if you know exactly one Mono-Red Aggro player, what if they’re wrong for that weekend? This was always an issue at Pro Tours: you could beat your team’s Mardu Vehicles list that was tuned with certain expectations or biases in mind, but if you look at the lists that made Top 8, you had no chance to win the event.

Really, the single best way to figure this out is usually playing longer Swiss events. Right now, that really means the SCG Tour Online or the weekend Magic Online Format Challenges.

When you test on the Arena ladder or in Magic Online Leagues, this is where you take a hit. Not that you won’t play against good players in those realms, but that you have to sift through a lot of other matches to get those. And it isn’t always clear across a bunch of matches against the same deck where the good, up-to-date players are, so it’s easy to come to bad conclusions and make a bad model for what you need to be doing. There are also issues with decks being over-represented in those settings because they complete rounds more quickly, or because they’re cheaper for idle play, or just because they complete “Play 30 White Spells” quests the soonest.

If you must derive things from small sample sizes, you should get the best sample possible.

With Swiss events, if you’re winning you’re playing against other people who are winning right now. Sure, maybe they got lucky, but more likely they’re doing something right and you want to make sure those are the people you’re beating. This is a bit less tangible, but people are actually sitting down and committing time to play a scheduled event as opposed to firing up matches as a secondary time sink. They care about the odds of having a great record, not just a 60% win rate over whatever sample size. The quality of opponent, the quality of opposing deck, and the odds you play the matchups that matter are just higher once you start getting into the 3-1 or better part of a bracket.

This doesn’t quite hold up for the 0-2 bracket, but odds are if you’re picking up a deck and starting off 0-2 with it, you might be reconsidering that choice.

An example of this from learning Four-Color Blink (Yorion): until I played against Jeskai Cycling a couple of times, there was a lot to be answered about the Zenith Flare end-game. Was there a safe life total where I could just tank the first Zenith Flare, or where I needed to really hold the line against early threats? How big does Zenith Flare get relative to how fast the Yorion deck can close out the game?

The answer was that the number on the first Flare didn’t matter too much. If they need it to deal fourteen, they can wait a bit. If the first Zenith Flare resolved, the Yorion deck didn’t deal huge chunks of damage and the lifegain was enough for a couple more turns of cycling into another copy.

You won the games by either killing them before they cast a Zenith Flare, or making your life total utterly unassailable with a hand of Negates or an Archon of Sun’s Grace. Chip shots from tokens didn’t matter a ton as long as you had a way to safely clean them up. The matchup was much less stressful as a result, and I was able to win by just focusing on not dying early and setting up a fortress of answers to Zenith Flare going late while worrying about the rest of their potential engines later.

Step 5: Expose Yourself to Broader Nonsense

The first four steps here will get you to the point where you “know how to play” a deck. Step five is just the nice-to-have knowledge, if you have time for it.

And that’s diving into the at-large metagame.

The long tail of deck mastery is knowing what to do in unique situations. As we move beyond the fiasco that was 2020 Constructed Magic, you can’t enter a large event assuming everyone is showing up with one of three Tier 1 strategies or is losing to those decks. People can play weird stuff again and win some rounds.

Modern over the years is really the highlight of this. Do you know your deck’s Merfolk matchup, its As Foretold matchup, its Dimir Inverter matchup? You probably won’t play against them in any given event, but the one time you do, you will really wish you knew what the general matchup looks like.

This is also where Leagues and the Arena Ladder are actually a good tool. You get to play against whatever people show up with, and at that point you’re less focused on precision and more on having a general idea of what to expect. Again, this is just another case of knowing how not to lose games in a horrible fashion because you already got that mistake out once and never will make it again.

I never quite got here with Four-Color Blink (Yorion), and at the end of the day I didn’t really need to. Kaldheim Standard just doesn’t have the breadth of relevant decks for there to be a gotcha moment. As with most steps for improving in Magic, this last step costs the most time and provides the lowest relative improvement.

And if your goal is getting good enough to maybe win an event quickly enough to play in it, you work with what you can get with the time you have and figure out that Slivers matchup on the fly.