One of the most subtle, yet powerful, qualities a Magic card can have is modality. There is a rich history of mechanics that provide players with a variety of options: cycling, split cards, and kicker, to name a few. But modal double-faced cards (DFCs) take this to the extreme. This mechanic will go down as one of the most fundamentally impactful mechanics of all time. The upcoming Draft format will break common heuristics and deckbuilding will require innovation. My goal today is to get us all thinking about how we need to reframe our perspective in order to best utilize modal DFCs in Zendikar Rising Draft.

Hour of Devastation is a fan-favorite Limited format thanks to the popularity of multicolor decks enabled by Oasis Ritualist. However, Oasis Ritualist was not the most impactful common towards the fundamentals of that format; cycling Deserts changed the game.

The best decks I drafted in that format played around nineteen lands, and at least eight Deserts with cycling. This meant I could choose whether or not I wanted more or fewer lands. If the current situation required a higher density of spells, I just cycled my lands, no problem. If I needed to hit land drops in order to cast some big payoff, I could choose to put my Deserts onto the battlefield. Cycling on lands brought agency over mana, something Limited rarely provides. This placed the Deserts as either the best or second-best commons in their respective colors. And getting a density of them was one of the best avenues to success in that format.

According to the math, modal DFCs are actually more common than Deserts were in Hour of Devastation. With five commons in a small set, the expectation is that a Desert is in five out of every seven packs. This means there were around eleven or twelve Deserts in Hour of Devastation Draft on average. With a modal DFC in every pack, they are twice as common as those Deserts. Hence it is significantly easier to draft a density of modal DFCs than it was to draft a density of Deserts.

To push it even further, modal DFCs are also more powerful and consistent than cycling lands. The agency provided by cycling lands let players make a choice: would they rather have a land or a spell? If they wanted a spell, they had to pay two mana to cycle the land, and there was always still around a 40% chance to draw into a land anyway. Modal DFCs, on the other hand, are always that spell if that’s what the player wants. That agency regarding land or spell moves from exercising probability to certainty.

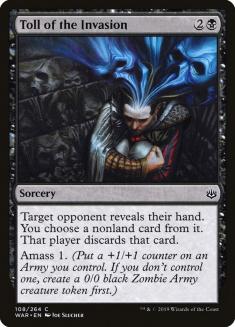

Certainty is valuable, and since cycling lands were 40% land, 60% a random spell in your deck, consider conceptually inflating the value of the spell side of modal DFCs proportional to that extra 40%. A three-mana discard spell is usually quite poor, but we have seen that it only takes a little bit extra to make them solid cards, as with Toll of the Invasion. I expect Pelakka Predation to be better than almost every common. The ability to play a conditional, yet sometimes very impactful, effect as a land is awesome. Hence, whatever the spell sides of these cards are, they are better than they read. You only cast the spell if it is impactful, and that requires a more optimistic lens than usually employed for card evaluation.

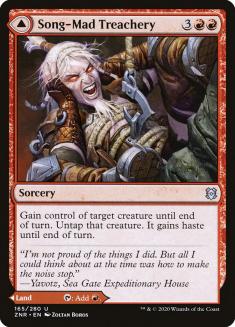

I strongly suggest looking at these cards with that optimism. If most Draft decks don’t care for Fling or Act of Treason, why should they care about paying more mana for those effects? Kazuul’s Fury, Makindi Stampede, and Songmad Treachery all fill the role of game-ending spell through facilitating the final points of damage. Historically, these clunky spells are not worth the inclusion because they’re effectively mulligans until the exact point they are useful: getting in those last points of damage. And if you fall behind, that opportunity never presents itself.

Notice how the reason to exclude these cards is that they are only useful in a specific circumstance, and that usefulness isn’t worth the risk of a dead card. But what if there is no risk? What if you could always play the card as a land? It may seem ridiculous to spend five mana for Act of Treason, but I’m excited to put Song-Mad Treachery in my deck, and you should be too!

In fact, it’s very clear these cards are designed with this in mind.

The above two-drops are all about on-rate for their cost. However, they’re not the most absurd uncommons in the set. Don’t get me wrong — I still expect them all to be better than almost every common — but what matters here is how time affects modality. Both modes of all of these cards are optimized for the early-game. Later in the game, drawing a two-drop or Force Spike counterspell variant is quite poor.

Historically, modal spells are at their best when each mode provides very different options. Izzet Charm’s three modes all handle very different scenarios. One kills creatures, one handles noncreature spells, and the other loots a couple of cards away in the scenario where the other modes aren’t deemed useful. This card has what I describe as “full coverage.” No matter the scenario, one mode will be useful. Cards like Tangled Florahedron and Jwari Disruption have worse coverage than a card like Bala Ged Recovery that has an impactful mode in the mid- to late-game and also can be played as a land in the early-game.

While I have covered a variety of ways to think about this new type of card, I’d like to end with my current expectations for how they will impact draft prioritization and building deck manabases:

I plan on starting out the format by never passing these cards. I don’t believe they will be the end-all-be-all best cards in the format; however I think in order to figure out exactly how good they are, I will need to play with them a lot. I believe they will land in a they-should-never-wheel camp, but am not entirely sure if that means they should be aggressively taken early or not. That being said, I think the heuristic of “if you don’t know what to take, take the modal DFC” is a reasonable rule to fall back on.

As far as manabases go, this is explicitly dependent on the cards. A card like Jwari Disruption doesn’t count as a land in the same way Umara Wizard does. If you have five mana, Umara Wizard is almost always going to be a spell, and if you don’t, it’ll likely be played as a land. This means you can just cut a land for Umara Wizard. However, since Jwari Disruption is a bad draw late in the game, and best as a spell in the early-game, there isn’t such a clear-cut way to determine if a spell or a land takes the axe to fit Jwari Disruption in the deck. I still lean on the cut-a-land side right now, but I could see that changing over time.