After many bannings, Zendikar Rising Standard is finally in a good place. Most of the competitive population knew what was needed for the format to be restored to its former glory, but there were some delays that were obvious to just a few of us. Even though the world knew Uro, Titan of Nature’s Wrath and Omnath, Locus of Creation had to go, I wrote an extensive piece on why only half of that equation would come true a couple of months ago.

Zendikar Rising had just been released and Omnath made Standard a nightmare for most players. The matches against these big-mana decks were intricate and I enjoyed solving the puzzle; however, there were far more cons than pros. The format was a one-deck arena, even though stubborn folks liked me continued to play alternative strategies. There was one four-color Elemental king in town and anything else was a serf in power-level comparison. Removing Uro was the obvious move, but I knew there was no chance they would remove the flagship mythic rare from their newly released set.

After a few more weeks of misery, the team in Renton decided they could not ignore the issue any longer. There was no caped hero about to swoop in and solve the already-stagnant metagame. They announced an announcement and we all knew then what was about to happen. With the removal of Omnath, Standard has become the best it’s been in years.

The Zendikar Rising Standard metagame has opened up substantially, with dozens of different decks battling and taking down trophies. Although the MPL/Rivals folks solidified on a few choices, the overall metagame does not reflect their conclusion. A small tournament with the best players in the world, linked together in testing teams within, will shrink any metagame. Teams test, concluded what deck beats their anticipated metagame, then execute. This creates a homogenized event, which is not indicative of the format at large. With that being said, the event still had a nice compilation of decks, which would have been even more narrow if the bannings did not take place.

Last weekend’s Zendikar Rising League Weekend showcased some of the choices that have been popular in the mainstream. The choice of Azorius Blink was one that baffled me, a lover of this type of deck, because of how weak it is against the metagame. Even with additional cards, the spell quality is so weak that it often loses to Dimir Rogues. As much as I hate to say it, Charming Prince; Barrin, Tolarian Archmage; Alirios, Enraptured; and Solemn Simulacrum are just not good cards.

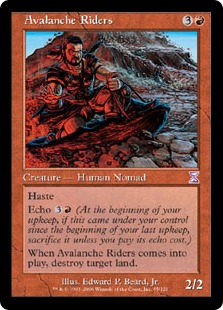

I was the architect behind Blink Riders back when Momentary Blink was invented, so I know a thing or two about bad cards re-entering the battlefield. In a grindy format driven by value, this type of strategy would be brilliant. Nickel-and-diming your opponent with a few extra lands, scrying, card draw, and creature tokens can be a winning strategy. This format is cluttered with a speedy Dimir Rogues deck that can apply quick pressure and then defend with blue disruption and removal. Once you add Gruul Adventures, Rakdos Midrange, Mono-Red Aggro, Mono-Green Aggro, and Golgari Adventures to the mix, the beatdown is real. Even the midrange decks listed can pack an early punch with some of their draws, making a play like Charming Prince on Turn 2 not ideal.

The evidence lies within the decks listed above. Formats are at their best when there is a pile of creature-based decks to choose from. This usually indicates that there are no must-plays from the creature world and the power level is even across multiple color combinations. In a world where there is this even power dynamic among the creatures, control is a viable counter to the metagame. I have learned this the easy way, comfortably sitting on top of the mythic rankings of MTG Arena (Arena) since the bannings took place. That has been primarily in the hands of Dimir Control, which I wrote about recently, and not much has changed since the article was released. It feasts on the midrange decks of the format, while having a decent game against the most popular deck, Dimir Rogues. Since I have not changed much with that deck, I wanted to present to you all another option that the recent professional event inspired.

Creatures (3)

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (30)

Spells (42)

I really enjoyed the premise of this Jeskai Control deck, but I felt it needed some additional modifications to be truly competitive. The mission of this deck is to cast Transmogrify on one of its many token creatures, putting Dream Trawler onto the battlefield. Normally these types of Polymorph effects should result in a game-ending win condition, but we live in a different world now. If the shell can produce significant pressure from other sources while deploying powerful disruption, Dream Trawler might as well be Emrakul, the Aeons Torn.

The original lists floating around, looking specifically at John Rolf’s and Will Pulliam’s, have more of an all-in feel to them. There are some aspects that I loved from each list individually, so my starting point was to merge the best aspects of each, and it has worked out very well so far. Rolf had a heavy focus on conditional counterspells in the maindeck, minimal sweepers, and a wild manabase. The genius in his build was including multiple copies of Ugin, the Spirit Dragon, which was lacking in Pulliam’s. Not including Ugin in today’s control decks is an unforgivable sin.

Creatures (4)

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (23)

Spells (30)

Creatures (3)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (34)

Spells (41)

Ugin is the most powerful card a control deck can summon, regardless of the archetype. My Dimir Control deck plays one copy, due to the amount of card draw to get to it. In these 80-card decks, a second copy makes perfect sense. It’s the best possible card to plan toward against nine of out ten decks in the metagame, since the vast majority are creature-centered. Even decks like Temur Ramp explode permanents onto the battlefield, making a follow-up Ugin game-ending. These two copies, alongside four Shatter the Sky, provide a rock-solid strategy against the extensive ground attack that exists in the current Standard metagame.

Another thing that I liked about Rolf’s version, compared to Pulliam’s, is the two copies of Elspeth Conquers Death. I’m fully aware the interaction that Yorion has with cards like this, which is why Pulliam had four copies, but it just does not work now. Dimir Rogues, led by Lurrus of the Dream-Den, has literally one target for the powerful enchantment to exile. Even though the other effects do something in that matchup, it’s not where you want to be in this metagame. The two copies that I play have been forgivable, because on the rare occasion I land one through disruption, I’m able to return a milled Ugin, the Spirit Dragon for maximum punishment. Using the graveyard to its fullest is the name of the game these days, especially when you know Dimir Rogues is the deck to beat.

The best part of Pulliam’s version is the inclusion of Yorion. It’s a free inclusion, adding depth to a deck that can get grinded out without any true card draw in the maindeck. One thing I miss the most about Dimir Control when playing this is not having access to Frantic Inventory. I have made some crazy additions to decks in the past, but I’m not signing up for Frantic Inventory in an 80-card deck anytime soon. Yorion lurking in the companion zone is the solution to a barrage of hand disruption, blinking those valuable Omens for an additional boost later in the game.

Regarding the Yorion synergy and maximum Elspeth Conquers Death that Pulliam played, there’s a shortage of targets in the planeswalker department. This is where I added Teferi, Master of Time in addition to the two Ugins to extract additional value. None of these modifications are providing a card here or there, but instead dealing with a battlefield that has gotten out of hand. There are few things sadder than having the final chapter of Elspeth Conquers Death resolve without a single option resting in the graveyard. My version of Jeskai Control attempts to repair these issues and maximize the power of the control elements without losing sight of the combo center.

Transmogrify is quite the dud when not hitting your own token, which explains the maximum amount of The Birth of Meletis in both versions. This was smart deckbuilding, especially in the metagame where early-game interaction and the life total is vital. The Wall token produced is sacrificed to retrieve a Dream Trawler, making it one of the best options to start the early-game with. Omen of the Sun, Shark Typhoon, Emeria’s Call, and Castle Ardenvale are the other methods to bring Dream Trawler onto the battlefield, but some received too many slots in the original versions. When additional copies of Transmogrify are drawn, or there’s no creature to target, cards like Fire Prophecy, Narset of the Ancient Way, and Teferi can be used to loot them away.

Shark Typhoon is the easy four-of in Jeskai Control, often defeating opponents on its own. There’s not a control deck in the foreseeable future, that this mage will wield, without multiple copies of this amazing win condition. Most folks on my side of the fence are very familiar with the power of Shark Typhoon and understand its permanent role in Standard control decks moving forward. Emeria’s Call, which was not in Pulliam’s deck, is another win condition that deserves at least a spot in every deck with white in it. I understand his reasoning for not playing it, feeling as his hand was forced when playing four Plains for his The Birth of Meletis and three Castle Ardenvale, but there’s compromise in the middle.

I am down to two Castle Ardenvale and it’s likely that I drop it to one copy soon. It’s the worst engine to produce tokens in the deck, especially in multiples, due to its Plains requirement to enter the battlefield untapped. Castle Ardenvale takes the place of an additional Emeria’s Call and some further testing will likely push me toward making additional 4/4 Angels. The DFCs are so powerful in control that it took everything in me to not put additional Sea Gate Restorations in.

As many of you are aware, I’m still convinced that Sea Gate Restoration is the most powerful DFC for control. With each passing day, more decks are including Sea Gate Restoration because they’re seeing the same results when casting it. In a deck like Dimir or Jeskai Control, setting up a giant card draw turn with one of these is cataclysmic for the opponent. The only issue is making room for all of these powerful effects, while keeping the mana distribution and untapped land count correct. The current manabase I listed is near-optimal but keep a lookout on Twitter (@shaheenmtg) for marginal upgrades I make while testing.

The sideboard for Jeskai Control can be tricky to craft. I was nearly in full agreement with Pulliam’s version, only being a few cards off myself. The big discrepancy was due to me having to put the other two Elspeth Conquers Death in the sideboard. With any white-based control deck, Elspeth Conquers Death should be maxed out. As discussed, when Lurrus is one of the top contenders, we must accept that some of these powerful enchantments will be stored in the sideboard for future battles. The rest of the sideboard mirrors his because he has successfully identified the metagame we all now face. Rolf’s sideboard was one that I could not connect with well. It seems all over the place, with cards that I would not personally play in Constructed Magic. In his defense, the competition in his tournament was very specific, making these cards a possible metagame targeted shot above my comprehension. For all of you playing in the real world, the sideboard that you see in my version will best assist you.

Jeskai Control has the tools necessary to easily handle the diverse metagame we all now face. The generic control spells keep most threats at bay but will ultimately put you behind against most strategies. It’s the four-mana Dream Trawler that puts this deck over the edge and immediately flips the advantage upon resolution. I look forward to opponents frantically trying to remove the hexproof Sphinx while attempting to thwart the control shell behind it.