Every time we have a Standard format, there’s a way of how decks plan to win the game that, even if we don’t realize it, we are all participating in. The ultimate goal of most decks in a Standard format is eventually reducing the opponent’s life total to zero or forcing them to draw a card from an empty library, but the way that decks get there can vary from format to format.

War of the Spark is a particularly interesting set to have introduced into Standard specifically because it has so many planeswalkers. As obvious a point as this is, what isn’t necessarily as obvious is how this completely warps the way that people will build their decks and the ways people will have to try to beat one another. Winning, after all, does involve defeating another living, breathing human that is just as interested in beating you as you are beating them.

When building a deck to play in Standard, in order to succeed, there are some clearly stated goals that your deck must meet in order to succeed, or it will fail to trump decks in these ways:

Tank Up

Creatures (29)

- 4 Llanowar Elves

- 2 Shalai, Voice of Plenty

- 2 Knight of Autumn

- 2 Deputy of Detention

- 4 Hydroid Krasis

- 4 Growth-Chamber Guardian

- 4 Frilled Mystic

- 4 Incubation Druid

- 3 God-Eternal Oketra

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (24)

Make the game as complicated as possible, and then assume that your pile of resources will be able to beat the opponent’s.

Most of the explore-fueled decks fall into this category. Remember how Sultai played last format? That’s more or less what this style of deck is trying to accomplish.

Looking at the Bant Midrange deck above, its whole purpose is cranking out a planeswalker ahead of schedule and then protecting it while it generates resources. After a few turns of this, the Bant deck gets around to winning via God-Eternal Oketra or a Vivien Reid ultimate.

These decks still have the “midrange” label because they’re able to use their creatures to apply pressure against any control or combo deck, but ultimately, they’re planning to use their creatures to try to defend.

Using Deputy of Detention in a deck like this will be different from using Deputy of Detention in something like Azorius Aggro. In Azorius Aggro, the goal is finding holes in defenses and simply trying to get as many creatures off the battlefield as possible.

In the Tank Up decks, however, Deputy of Detention more frequently will answer specific problems, and is used more conservatively as a result. This means sandbagging things like Deputy of Detention in order to answer cards that would otherwise be able to punch through defenses, like flying creatures, or permanents that otherwise invalidate a planeswalker, like Conclave Tribunal or Sorcerous Spyglass.

If your deck is more interested in casting a couple of creatures and defending a card advantage engine for several turns via resources on the battlefield before turning the corner, then it’s likely a deck that falls under the Tank Up umbrella.

Reduce Resources, Win With What’s Left

Creatures (11)

Planeswalkers (10)

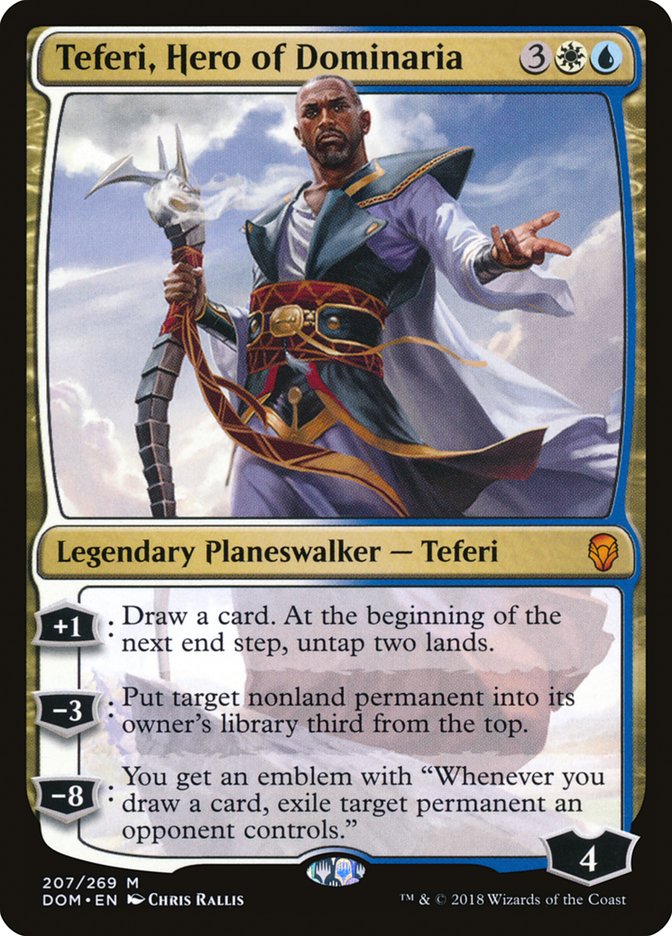

- 3 Teferi, Hero of Dominaria

- 2 Liliana, Dreadhorde General

- 3 Teferi, Time Raveler

- 2 Sorin, Vengeful Bloodlord

Lands (25)

Spells (14)

There are two ways to play a long game: make everything as complex as possible and then see who has more powerful synergies going on, or reduce both players’ resources and see who has the most powerful thing when the dust settles.

The Thought Erasure into Thief of Sanity line has become a hallmark of the current Standard format that is trying to squeeze the resources that players have access to in the early-game in order to create a makeshift protect-the-queen strategy around Thief of Sanity and the top of its opponent’s library.

The main point here is that the deck is proactively creating situations in which players are trading resources or the game is ending.

Rather than playing a million hand disruption spells, however, Esper Midrange accomplishes this by playing a pile of must-answer permanents that have the propensity to put the game out of reach if their controller ever gets to untap with them.

This creates a more natural form of resource-trading that doesn’t force the Esper Midrange player to commit to playing as many interactive spells, electing to put the ball back in the opponent’s court, effectively saying, “Deal with this, or run the risk of falling so far behind you won’t ever recover.”

Once resources have been traded, whittling both players down to only a handful of cards, the Esper Midrange deck uses its planeswalkers to gas back up and pull ahead of the opponent.

Standard Izzet Phoenix is another archetype that tends to operate on a similar axis, even if the payoffs are different in functionality.

This is how a good chunk of midrange decks have acted, historically, but the cards in this deck go bigger than previous iterations of the archetype, and this deck plans on using the opponent to trade resources, rather than having to commit slots in its own deck to doing it.

Play A Control Deck With A Card Advantage-Kill Condition Hybrid

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (26)

Spells (27)

Some people just wanna play Magic for all 50 minutes of a round and that’s okay. I guess.

As the header implies, the control decks are back to having to answer basically everything, because the biggest synergy decks in the format are “Play a bunch of creatures and planeswalkers for them to defend” and “Play a bunch of cantrips and payoffs for them.” It’s harder to just pick apart the important pieces of what a deck is doing, ignore the rest, and win through their leftovers.

Luckily, control decks currently have two of the best card advantage engines ever printed, so answering every threat the opponent can produce isn’t as tall an order as it sounds.

Traditional control shells are more or less at a point where the key to winning is answering every card the opponent casts to the point of being able to untap with whatever their game-ending threat is, and then riding that threat to victory.

This differs from previous control strategies because rather than playing cards that are exclusively finishers, the cards that control decks are currently winning with are also cards that work as card advantage engines. In other words, rather than running both Aetherling and Sphinx’s Revelation, Esper Control and friends are consolidating those pieces into smaller slots on their decklists. This means there are fewer clunky draws that struggle to interact early on, and a lowered chance of running out of things to do as a result of drawing something like Chromium, the Mutable too early.

Go Under Them

Creatures (20)

- 4 Fanatical Firebrand

- 4 Ghitu Lavarunner

- 4 Goblin Chainwhirler

- 4 Viashino Pyromancer

- 4 Runaway Steam-Kin

Lands (20)

- 20 Mountain

Spells (20)

This is where the aggro decks live.

Rather than trying to do anything involving card advantage, these decks try to convert their cards to damage.

Pretty straightforward beatdown stuff.

What’s slightly different about these flavors of beatdown is that they’re being forced to play tools that can rumble into the later-game.

We saw this type of trend happen during last Standard format with the Ramunap Red decks, but the existence of Goblin Chainwhirler in particular is to blame for these decks having the ability to play into the later stages of the game.

A thousand articles have already been written on The Chainwhirler, but to sum it up: Goblin Chainwhirler is great at mopping up permanents that would normally hit the battlefield before it, and has a reasonable enough size to combat things that come after it, due to its first strike comboing so well with burn spells. Without this effect, the go-big plan seen in the sideboard wouldn’t be remotely as possible.

It’s not an accident that almost the entire sideboard is comprised of cards that help the deck go bigger when necessary. It’s not a matter of “if” it’s going to be going bigger in post-sideboard games, but “how.” The reason for this is in the cards that these decks have to face:

A lot of the free wins that aggro decks get before sideboarding lie in the fact that, before sideboarding, other decks will have more expensive cards that are dead in the early stages of the game. Mono-Red and the White/X decks kill decks while they’re still setting up.

After sideboarding, it isn’t so easy. Once they’ve had the opportunity to shave their bigger cards, the opponent is more readily able to bridge the gap to the mid- and late-game, where they plan to go over the top of what the aggro strategy is doing. This means that the aggro strategies need to have some sort of plan for what happens when they inevitably arrive to the mid- and late-game.

In Mono-Red Aggro’s case, that means shifting gears a bit and playing a strategy that can play to the mid-game by playing different types of threats that require different kinds of answers. The same cards that beat Rekindling Phoenix aren’t going to beat Tibalt, Rakish Instigator; aren’t going to line up well against Experimental Frenzy; and so forth.

Creatures (26)

- 3 Adanto Vanguard

- 4 Skymarcher Aspirant

- 4 Snubhorn Sentry

- 4 Benalish Marshal

- 4 Dauntless Bodyguard

- 4 Venerated Loxodon

- 3 Law-Rune Enforcer

Planeswalkers (4)

Lands (20)

Spells (10)

For the White/X decks in the vein of Azorius Aggro, that’s more frequently going to translate to things that make it more difficult for the opponent to interact with its primary game plan. White has a much harder time going big in ways that can stand up to the card advantage engines of the slower decks in the format, so this means that it’s better to try to use things like counterspells and removal to just get things out of the way of the pressure being applied.

So what does all of this mean?

It means that if your plan is to be aggressive and go under what other people are doing, be sure that you’re coming to play with something to do once the opponent has sideboarded as well. It’s okay to lean into the plan that you had for Game 1, but don’t assume that the exact same configuration will go as well the second time around.

Subvert Expectation

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (25)

Spells (32)

- 4 Opt

- 4 Search for Azcanta

- 1 Blink of an Eye

- 4 Nexus of Fate

- 4 Root Snare

- 2 Sinister Sabotage

- 4 Chemister's Insight

- 4 Growth Spiral

- 4 Wilderness Reclamation

- 1 Callous Dismissal

Sideboard

Sometimes, your opponent sits across from you with the expectation of playing a game of Magic: The Gathering, and you sit down with a deck of Ascension deckbuilding game cards. Then it’s up to your opponent to beat you before your Ascension deck goes infinite.

All kidding aside, the best way to go rogue in this format is to win out of nowhere, in a way that is difficult to interact with, via some sort of combo.

Creatures (2)

Lands (25)

Spells (33)

- 4 Opt

- 2 Lightning Strike

- 1 Gift of Paradise

- 2 Search for Azcanta

- 2 Fiery Cannonade

- 3 Shivan Fire

- 3 Sinister Sabotage

- 4 Chemister's Insight

- 4 Expansion

- 4 Growth Spiral

- 4 Wilderness Reclamation

Sideboard

The easiest way to do this in today’s Standard is with some Wildneress Reclamation-fueled nonsense, but it isn’t the only way. The biggest reason that a card like Wilderness Reclamation is important in these sorts of strategies is it is one of the biggest cards that lets its controller skip so far ahead in terms of development.

The decks that want this type of effect are trying to do something that is firmly in unfair territory, without paying any huge deckbuilding costs. These decks can tread water during the early stages of the game and then skip directly to killing the opponent via some means that rarely feels like a traditional game of Magic.

Actionable Information

The big takeaway from all of this shouldn’t necessarily be to try to make your deck exactly line up with what these decks are doing. It should instead be to understand what sector your deck occupies and how other people will try to fight against you.

Taking it a step further, understanding how decks want to operate in a given format will make sideboarding that much easier when playing against something never seen before.

Sure, you may have never played against a certain flavor of control before, but knowing how to fight against removal-plus-Teferi will give you an idea of how to operate against the newcomer. Apply similar theories to other archetypes, and you start to see the matrix behind Magic, allowing you to see things in the macro of a format, rather than the micro of the cards in it.