For years, it’s been popular among highly competitive players to complain that the problem with Modern is that there are too many non-games. There are a lot of “Game 1 decks,” proactive decks that beat most people who don’t have specific answers for them, and when two Game 1 decks play, there’s often a “ships passing in the night” feel; the decks don’t interact and it’s just a straight race. Then, after sideboarding, games have often come down to whether the player who isn’t playing such a deck draws their sideboard card: Stony Silence against Affinity, Blood Moon against Amulet, Leyline of the Void against Dredge, etc.

These days, the landscape has changed. Sideboards aren’t relying on single bullets, and there’s always counterplay to the strongest bullets.

Why is this?

To start with, Izzet Phoenix has become the driving force in Modern and this deck simultaneously plays so many gameplans that this approach really doesn’t work. Arclight Phoenix attacks in an entirely different way and demands entirely different answers from Thing in the Ice, and Pyromancer Ascension attacks in another different way as well. Crackling Drake is somewhat similar to Thing in the Ice, but meaningfully different.

Also, the deck does very powerful things at every stage of the game, so it can be difficult to pin down a particular role against it. There are some effective hate cards against the deck, like Chalice of the Void, Rule of Law, or Trinisphere, and some cards that people try to use as hate cards that aren’t very effective, like Rest in Peace. The artifacts mostly just slow them down and it’s possible for them to counter or remove them or win through them if they aren’t backed by pressure. They’re also pretty narrow, and more well-rounded hate cards like Damping Sphere are much less effective.

In general, I think the best plan to beat Izzet Phoenix is to just do a better, faster thing. It’s easiest to win Game 1 against them, because they’re very good at using cantrips to find sideboard cards, so sideboarding in general is more effective for them, and their Game 1 deck has very little interaction, so it’s easy to do something they can’t really interact with. This is why I play decks like Dredge and Lantern, but Amulet Titan or Tron would work similarly.

Anyway, there’s more to the format than just beating Izzet Phoenix, and fair decks have never been the driving force behind sideboard decisions, so there’s more going on here than just that. A lot of it is that decks are less vulnerable to hate.

Dredge players have learned that the most effective sideboard cards against them are artifacts and enchantments, and they play three to four Nature’s Claims in the sideboard as a result. Amulet Titan no longer folds to Blood Moon – they play more basic Forests, Coalition Relic, and answers to enchantments. Stony Silence isn’t effective against all artifacts and those decks that it is effective against tend to be good at removing it.

I can’t think of any common matchups where I feel like, if I mulligan to a particular card, the fact that I have that card will make me more than 70% likely to win a game, and that’s not how it used to be.

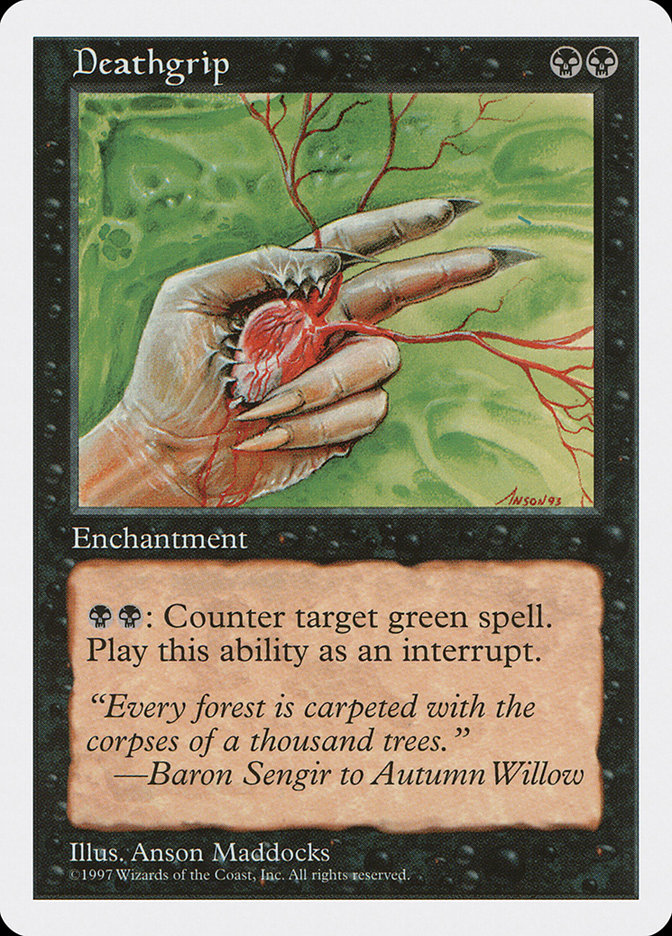

Ever since Alpha, there have been two basic kinds of sideboard cards – cards that look to win a game essentially by themselves, like Deathgrip or Conversion; and cheap, versatile interaction, like Red Elemental Blast. Somewhat remarkably, to my mind, Red Elemental Blast has better withstood the test of time – a simple effect at a great rate has outperformed super-high-impact lockout-type cards. Modern sideboards currently lean on more cards like Celestial Purge, Dispel, Surgical Extraction, and Ceremonious Rejection, and less on Stony Silence, Rest in Peace, and Blood Moon. All of those are still played and still very good, and I just think they define fewer games than they used to.

When the haymaker sideboard cards are played, they tend to be strong cards rather than game-enders. So what does all this mean? Why does it matter? How does thinking about this help us win more?

First, it means there are more good games of Modern. That’s a nice perk that makes the format more fun, but noticing it doesn’t help your win rate unless it makes you more interested in testing more or something.

Game 1 in a match of Modern legitimately can often be minimally interactive. In most matchups one or both players will have a few cards that can directly trade with the opponent’s cards, but looking at the game as a pair of competing narratives, or maybe as a debate, it will be won more by talking over the other person than by contradicting their argument. Game 2 will be a slower, less heated, more reasonable discussion.

There’s this idea about mulliganing for a sideboard card – that’s not a real thing these days. What I mean is that it should never be your plan. Game 2 is going to be scrappier and more interactive. If you find your sideboard card, there’s a good chance they’ll have their countermeasure, so don’t plan to mulligan to five looking for it. You must plan to play a normal interactive game of Magic and you want the tools to do that.

Your Modern sideboard should look more like a Standard sideboard with cheap interaction and good “Game 2 cards” – think card advantage that attacks from a different angle from what your opponent was expecting (planeswalkers are the go-to here). Izzet Phoenix is way ahead on this front. Yes, they play a couple of haymaker-type cards like Blood Moon and Shatterstorm, but for the most part, it’s Abrade, Ceremonious Rejection, Dispel, Echoing Truth, and Spell Pierce, backed by cards like Chandra, Torch of Defiance.

The top line here is certainly “expect to trade cards more after sideboarding.” This means you should mulligan less and choose to draw more. Conventional wisdom says that you always want to be on the play in Constructed in all but weird corner cases like playing Manaless Dredge, but the reality is you want to be on the draw surprisingly often in Modern. Grixis Death’s Shadow is a deck that’s full of one-for-one card exchanges where mana doesn’t really matter – all of their cards cost one but they’re not trying to end the game on Turn 3 and their threats don’t come down on the first turn, so very often, the extra card is what’s important. Izzet Phoenix is similar. They’re a critical mass deck. Their spells are cheap and they need to cast a lot of them. If you have Thoughtseize, there’s a good chance you want to be on the draw so that you can try to just run them out of resources so that their cards don’t work very well.

The fact that everyone’s trying to play a fairer game after sideboarding and coming prepared with alternate win conditions or plans to answer your sideboard cards also means that you want to prioritize sideboard cards that are hard for the opponent to interact with. This means more Ravenous Traps and fewer Leyline of the Voids, yet this advice doesn’t always apply.

You need to understand how the game is going to play out after sideboarding and what level of impact versus consistency you need. If you’re playing a deck that’s reliably a turn or two slower than Dredge and you just need to buy a little time, you might want something hard for them to interact with that will reliably make them stumble a little, like Ravenous Trap or Faerie Macabre, but if you’re playing a slower deck with a worse matchup, you might need to lean more on a high-impact card like Leyline of the Void or Rest in Peace, especially if you can protect it with discard or counterspells.

The point is, after you’ve sideboarded, you still want to present a deck that’s going to play to a coherent narrative that you know how to execute. Don’t just stop at a headline; “Azorius Control Player Casts Rest in Peace” isn’t a winning narrative these days. That’s just something a Dredge opponent expects to happen, and they’ll be prepared to answer it and then do something explosive, because the Azorius Control deck will give them plenty of time.

Modern is currently dominated by hyper-consistent decks. The best cards are Ancient Stirrings and Faithless Looting. Decks that use these cards play out more or less the same way every game, and the London Mulligan will only make that truer. You can use that to your advantage. If you know exactly how every game is going to play out, you can identify exactly where you need to be able to interact to come out on top.

Just remember that things get scrappier after you sideboard. Izzet Phoenix will have more counterspells and more removal. Death’s Shadow will have planeswalkers. Amulet Titan will have a wider variety of green creatures, like Hornet Queen. Dredge will have Nature’s Claim, but also creature removal and sometimes discard, or narrow hate like Damping Sphere. Every deck must give up some consistency/aggression/proactive power to accomplish this, so the game slows down.

I’ve been told that the way that I sideboard with Dredge is unusual because I’m willing to change more cards than other people. I’m willing to fundamentally transform what my deck does if I think the specific cards it uses won’t line up well in a match. Someone might look at my deck after I’ve sideboarded out a lot of my creatures and criticize me, saying “my deck doesn’t work,” but that’s not true. It doesn’t do what it did in Game 1, but it’s still functional; it just works differently. It is possible to over-sideboard, especially with a combo deck, and present a deck that doesn’t have a gameplan, but when I make these kinds of changes, I know what I’m trying to do, and I understand how the changes I’ve made will impact how my deck plays out. That’s the important part.

There’s also a lot of room to get creative in sideboarding. If your opponent is expecting your deck to play out in a certain way – to do the very consistent thing it did in Game 1 – you can potentially get a large edge by doing something they didn’t expect. Ad Nauseam has done this by sideboarding in random big creatures like Dragonlord Dromoka or Grave Titan to punish people for cutting removal. Izzet Phoenix can cut almost all its creatures and become something more like Blue Moon if a matchup calls for it.

I’m not saying you need to overhaul your sideboard immediately. I’m not saying all the high-impact cards are wrong. To summarize, my points are:

1. Expect better, more interactive games of Modern after sideboarding than we had years ago.

2. Expect your opponent to try to react to predictable, high-impact cards and consider using lower-impact cards that are harder for your opponent to interact with or less expected to circumvent that, so long as your deck can present a reliable way to win with the smaller effect.

3. Make sure your sideboard plan isn’t just a list of cards that come in and others that go out, but includes an understanding of how the game will play out, how you can lose, and what you need to do to win.

4. Remember when making this plan that games are going to involve more interaction and trading, so sources of card advantage or unexpected angles of attack that your opponent won’t have an answer to are particularly important.

Sideboarding is messy and complicated, and I’d guess that almost any matchup tends to get closer to 50/50 after sideboarding, as the deck with the worse matchup usually changes more to improve it. There are exceptions, especially for unexpected decks or decks with fantastic sideboard plans, but for the most part, the biggest edge is going to come in Game 1 and then things will normalize somewhat. Personally. I’m a huge fan of winning Game 1, which is why, as always, I’ll be looking to play a proactive deck that my opponents aren’t ready for.