Since the format’s inception seven years ago, the hallmark of Modern has

been its diversity. When you enter the format, you’re told that there are

30, 40, …even 50 viable archetypes that will give you a good chance to win

the tournament, so long as you know your deck and its matchups against the

field well and tune it appropriately for that weekend’s metagame.

For many, the ability to build a deck or two and play them over a long

period of time without the format ever growing stale is its primary draw.

The format simply has more replay value than Legacy, which up until

recently was dominated by Grixis Delver, and Standard, which rotates and

means you must always stay current.

Unsurprisingly, this core aspect of Modern is also the source of criticism

from the format’s detractors. For them, the sheer volume of decks they must

be aware of makes the format too volatile. You can show up to a Modern

tournament with a decklist perfectly tuned to beat the top decks for the

weekend and run into Taking Turns, Burn, and Abzan in the early rounds, all

of which you cut sideboard cards for to make room for Ironworks hate and

extra cheap removal for Humans.

Modern is supposedly too diverse to sufficiently sideboard for every

conceivable matchup, so you end up picking your poison and hoping to dodge

the land mines. Of course, there are also the reverse land mines, where

you’re hoping to also avoid players that came particularly prepared for

your deck because the sideboard cards in Modern are so powerful.

Whether you love it or hate it, both sides agree on one thing: Modern is an

incredibly diverse format.There’s only one problem here: that’s just not

true. Modern’s diversity is an illusion. A self-fulfilling prophecy that

players who are attached to their subpar decks perpetuate so they have a

basis on which to rationalize their poor decisions.

Of course, it’s important to understand what we mean by “viable.” In his

article from last week about the fundamental flaws of Jeskai Control, Gerry

Thompson defines viable as “capable of winning a tournament.” By this

definition, I agree that Modern has a huge number of viable decks, but I

disagree that such a delineation is useful. Our goal as competitive Magic

players is to put ourselves in the best position to win tournaments and

casting a wide net in defining viability equates the small set of decks

which actually accomplish that goal on a consistent basis with the large

swath of them that don’t.

A good player with knowledge of their deck can, and often do, win despite a

significant handicap. This is part of what makes discerning the best decks

from the pretenders so difficult. There are so many variables in a Magic

tournament that we’re forced to make inferences from unclear data, and that

murky data is also used to justify poor deck choices.

“Deck A won/Top 8ed the last big tournament, it can’t be bad!”

Creatures (20)

- 2 Birds of Paradise

- 4 Bloodbraid Elf

- 4 Arbor Elf

- 3 Inferno Titan

- 1 Courser of Kruphix

- 2 Pia and Kiran Nalaar

- 4 Tireless Tracker

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (21)

Spells (17)

Yes, it can. If you can’t justify why you’re playing the deck you are with

fundamentally sound evaluations of its matchups, then you probably

shouldn’t be playing it.

The notion of Modern’s diversity being a ruse crystallized for me when

looking at the metagame breakdown from last weekend’s Pro Tour 25th

Anniversary. The top six decks, Humans, U/W Control, Ironworks, Mono-Green

Tron, Hollow One, and B/R Vengevine take up 62% of the metagame, a huge

share compared to major Modern tournaments earlier this year.

By comparison, if you look at the Day 2 metagames for the last four Modern

Opens, metagames where we’d expect the top decks to take up a larger share

because the picture is taken later in the tournament, the top six decks

take up anywhere from about 33% to 50% of the field.

The Pro Tour was a team event while those Opens were individual affairs,

but if I’m being honest, I would say that last weekend’s Pro Tour is the

most accurate representation of the Modern format we’ve had in quite some

time.

First, by virtue of being the Pro Tour, it has the highest average skill

level of its participants and the stakes are high enough that the vast

majority of the field is coming in well-prepared and trying to be as

objective as possible. At Opens and Grand Prix, you’ll have a significant

portion of the field entering for fun where winning is viewed as a

potential bonus, not the overriding goal. You also have players entering

who, whether it’s all they can access or a personal attachment, only play

one deck regardless of its viability.

The Pro Tour has Greg Orange and Guillaume Wafo-Tapa who only play control

decks and every player has some biases, but I’d submit that on the whole,

the level of bias is significantly lower and the vast majority of the

players last weekend spent significant time preparing to find the

objectively best deck for the tournament.

Furthermore, the nature of team events discourages the risky behavior

that’s often used to justify playing subpar decks. When a player is

deciding between an established archetype and a fringe one, the idea of

taking the field by surprise is alluring. It can be easy to look at the

established archetype as one that is likely to yield a mediocre result

while the fringe one could potentially spike the tournament but is just as

likely to yield an early exit, and the latter spread of results is

preferable. In reality, there’s no deck that’s more likely to top 16 while

another is more likely to top 8 or scrub. One of the decks is better and

the better deck is more likely to do well.

In team events, players are held in check by the fact that they’re playing

for more than just themselves. No one wants to be the weak link that needs

to be carried through the tournament because they insisted on playing their

pet deck. This makes players more apt to choose a safe deck, and the safe

decks are safe for a reason: they’re the best decks.

Looking at the Pro Tour metagame closely is particularly telling. Among the

top six decks there is a disruptive aggro deck (Humans), a control deck

(U/W Control), a combo deck (Ironworks), a ramp deck (Mono-GreenTron), and

two resilient aggro decks (Hollow One and B/R Vengevine). This is diversity

in some sense. There’s representation of nearly every macro-archetype save

for midrange and tempo, but in all but one category, there’s a single

representative for each macro-archetype.

It’s a common adage in Magic that you shouldn’t play a worse version of

something else. These are the top decks because they’re the only ones that

aren’t a worse version of something else.

As for the roughly equal presence of Hollow One and B/R Vengevine, the

latter was the new comer to the metagame due to the recent printing of

Stitcher’s Supplier. That the archetype isn’t fully explored is clear from

the diversity among decklists. Here’s three I found while browsing the

Modern lists:

Creatures (35)

- 3 Bloodghast

- 4 Goblin Bushwhacker

- 4 Vengevine

- 4 Viscera Seer

- 4 Gravecrawler

- 4 Endless One

- 4 Insolent Neonate

- 4 Walking Ballista

- 4 Stitcher's Supplier

Lands (17)

Spells (8)

Creatures (34)

- 4 Goblin Bushwhacker

- 4 Vengevine

- 4 Viscera Seer

- 4 Gravecrawler

- 4 Hangarback Walker

- 4 Insolent Neonate

- 2 Haunted Dead

- 4 Walking Ballista

- 4 Stitcher's Supplier

Lands (17)

Spells (9)

Creatures (34)

- 2 Greater Gargadon

- 4 Bloodghast

- 2 Goblin Bushwhacker

- 4 Vengevine

- 4 Viscera Seer

- 4 Gravecrawler

- 2 Blood Artist

- 4 Insolent Neonate

- 4 Bomat Courier

- 4 Stitcher's Supplier

Lands (18)

Spells (8)

There’s clearly an agreed upon core here, but between whether to add some

green, the variance in additional graveyard enablers and sacrifice outlets,

the choice on whether to add Bloodghast or not, among other differences,

the B/R Vengevine deck isn’t as well-tuned as the other top decks. There’s

something powerful there, and I expect it to stick around moving forward,

but whether it displaces Hollow One as the premiere resilient aggro deck of

the format remains to be seen. Though I do expect that one of these two

will eventually push the other to the fringe of the metagame.

Right now, I don’t see the B/R Vengevine deck being enough more explosive

than Hollow One to justify its increased vulnerability to graveyard hate

and the fact that the deck doesn’t have room for even the bare amount of

interaction that Hollow One has, but with proper tuning it could certainly

get there.

For a more detailed breakdown of the best decks in Modern, keep an eye out

for Todd Stevens’ article later this week, but my purpose today is to

stress that if you’re going to play a Modern tournament in the coming

weeks, you better have a very good reason for not playing one of these

decks. And no, “Jund is the deck I know/like the best” isn’t a good reason.

Put in the time and learn a better deck.

Hold on, Ross. Haven’t you been playing Blue Moon for the last few months?

I don’t see that deck on your fancy list.

You’re right. I should’ve put Blue Moon down a while ago, or better yet

never picked it up in the first place. When I first played it, I was under

the mistaken impression that it would be comparable to the other control

decks against most aggressive strategies while significantly better against

combo and big mana.

As I learned the deck, I realized that the creature decks weren’t as good

for Blue Moon as I anticipated, but the control matchups were excellent.

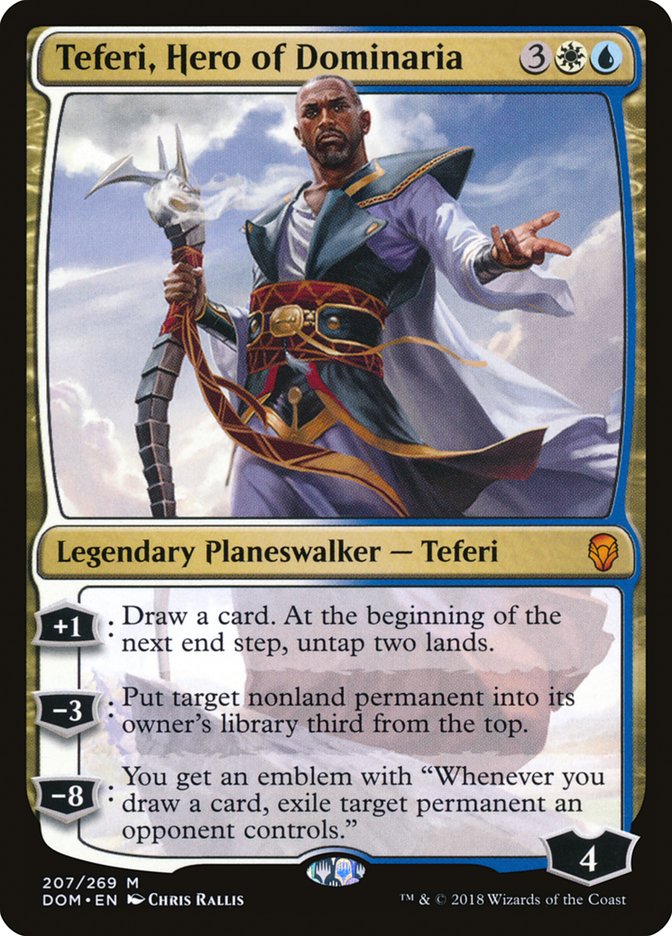

The metagame shifted heavily towards control as the Teferi, Hero of

Dominaria hype train was running full steam ahead and there were a couple

weekends where Blue Moon was indeed well-positioned. That time is now gone.

The rest of the 50 decks that are capable of winning a Modern tournament

all have specific metagames that are so favorable for them that they rise

to the level of the top decks in the format, but playing them is still a

mistake in the big picture because they never rise above that level.

In order to get to the point where I realized Blue Moon was well-positioned

enough to play it over the top tier, I had to sacrifice equity in the

tournaments where I was initially learning the deck. I would’ve been better

off playing a tier one deck that was good against control strategies, like

Tron or Hollow One.

So, while there are plenty of decks in Modern that are capable of winning a

tournament, what separates the top decks is the ability to withstand all

but the harshest metagames and still perform well. And this much stricter

criterion is a lot more helpful in determining a deck choice.

It took a metagame filled to the brim with control decks and Mardu

Pyromancer to put a stop to Humans, and as soon as Ironworks and Tron

showed up and punished players for packing their decks with creature

removal, Humans immediately bounced back. A deck that can kill on turn 4,

has around fifteen pieces of disruption, can operate on two lands, and

rarely floods due to the presence of Horizon Canopy is going to be good

against most decks. You don’t have to make it anymore complicated than

that.

Of course, players are still going to play the decks they want to play so

you have to be prepared for matchups outside the top tier, but if you take

another look at those six decks you’ll see all but U/W Control are

proactive strategies, meaning they will often be able to ignore what the

less powerful decks in the format are doing. And it’s no surprise that U/W

Control is the most proactive of the control decks, featuring a heavier

suite of planeswalkers, a full set of Celestial Colonnades, and maindeck

Vendilion Cliques. To consistently beat a wide array of decks you must be

able to execute a consistent gameplan and it’s impossible to do that with a

purely reactive deck.

We went through a similar phenomenon in Legacy during the height of that

format five or so years ago. Everyone touted Legacy is an incredibly

diverse format with many different viable strategies. The reality was that

there was a small handful of good blue decks, a larger handful of mediocre

blue decks that earned their place by playing the same powerful core as the

best blue decks, and the few combo and non-blue decks that could compete

with them. No one who was serious about winning a Legacy tournament was

registering Nic Fit, and it wasn’t because of the ridiculous name.

To some degree, this is all an exercise in semantics. Plenty of people play

the subpar decks, they show up on coverage, and they’re good enough to do

well in a tournament. Maybe that’s all you care about when it comes to

defining diversity. But the reality is that diversity is used by countless

players to play subpar decks at tournaments and you would all do yourselves

a service by not falling into the same trap.