Information availability in Magic is in a strange place. There’s more Magic

content being produced right now than at any other point in the game’s

history. Podcasts, streams, YouTube, StarCityGames – if you’re trying to

make informed decisions about card evaluations, deck choices, or any other

potentially divisive topic, the tools required to inform yourself are

available.

Well, most of them. One thing that remains noticeably absent is large scale

data collection. In Magic, we’ve spent years basing our conclusions on

preposterously small sample sizes, making the ability to get a “feel” for a

matchup quickly an invaluable part of any top tier player’s arsenal. While

we have Magic Online results doled out to us in bite-size morsels, other

card games such as Hearthstone and Artifact are crowd-sourcing data

collection, and producing regular metagame assessments that are

authoritatively identifying the best decks and cards.

Should we be jealous of our cyber-cardboard slinging compatriots? In some

ways, I envy their ability to cut down on time spent figuring out the

question to ask (e.g. what beats Boros Aggro?) and just get right to

figuring out the pertinent answers (e.g. basically everything). At the same

time, it feels like perfect data would take away an element of discovery

that has been with us since the nascent days of Magic. I like

figuring out the questions to ask, and I think a lot of players are with

me.

But quite honestly, it doesn’t matter what we like. Crowd-sourced data

collection has begun to propagate around Magic subreddits and

twitterspheres, and each month seems to yield better and better metagame

analyses. Sample sizes are getting bigger, and while they’re still not at

the point where they’re pushing us towards definitive conclusions, I’m now

using these efforts to inform my own study by letting them guide me towards

testable hypotheses.

I recently had the chance to chat with a friend of mine, Matt Nelson, who

spearheaded one such data-collection effort focused on the Modern

tournament held earlier this month at Grand Prix Atlanta. You can see his

team’s full report

here

. We’ll get to some of the more surprising results of this analysis in a

bit, but I want to share Matt’s thoughts on how he views data collection

efforts and what he thinks about this new chapter in competitive Magic’s

history.

Bryan

: What made you want to take on this project? Do you have any background in

data collection and analysis?

Matt

: I was really inspired by Joan García Esquerdo ( @jge_ryu on Twitter), who shared

his work on the handful of European Grand Prix in the GAM discord this

summer. For the first time since MTG Goldfish stopped posting matchup

percentages, we saw hard data about what decks were thriving, what decks

were surviving, about metagame shares, and about win rates in general. Joan

being European-based, I hadn’t seen anyone do similar data on American

Grand Prix – Logan Nettles had done some analysis of MTGO Modern PTQs that

he had participated in but nothing about paper Magic – so I wanted to step

up and start cataloging ours here. I reached out to Joan to see if he was

interested in collaborating. He was and here we are.

I did some really, really minor (I can’t overstate how minor) research in

graduate school, which mostly helped train me in how to use various online

data collection services like Survey Monkey and Google Forms. I want to

give so much credit to Joan for his work in terms of running analysis on

the data himself; he does the excellent data visualization you see when you

look at the link we posted, and I’m so grateful to have him as a partner in

this work. My day job involves working for university safety and data is

important there for identifying long term, larger scale trends. If

anything, I have more training in qualitative research as I did post-grad

work in anthropology and ethnographic research. I’m learning a lot about

data analysis myself as I’m trying to figure out how we want to improve and

advance our work. I have a long way to go.

Bryan

: Data collection efforts in Magic seemed to have lagged behind similar

efforts in other popular card games. Why do you think that is?

Matt

: Like many Magic players, I don’t exclusively play Magic. In Hearthstone

there is a group called Vicious Syndicate (“VS”) that does weekly data

reports on the meta. Hearthstone players opt in to submit their data, from

all variety of competitive levels in their ladder system, including their

elite level of “legendary” players. VS then combines thousands upon

thousands of matches into their weekly reports, showing numbers on expected

meta representation, representation over time (since they’re tracking

online play they can show the wax and wane of specific decks, as the

Hearthstone meta is constantly moving), and present some of the best

performing decks in the meta. With such a large data set, they can make

some powerful statements about the meta, where it’s at, and where it’s

going. It’s huge and absolutely essential resource if you’re a Hearthstone

ladder player.

I should note that VS is independent from Blizzard, whereas we get our

information from Wizards’ coverage. But contrast this with Magic, where we

get league results a couple times a week for Standard and Modern. These

results tell us mostly nothing, since the way they have compiled league

results prevents similar decks from being shown and they take place over

several days, so you can’t speak with confidence about the rise and fall of

specific strategies in the online meta. Larger events like MTGO challenges,

PTQs, Grand Prix, and StarCityGames.com events just give us the top

performing decks of a tournament, but not how the games played out and how

those decks were successful, which is the much bigger question. And

answering that question is what professional players are doing in the weeks

leading up to the Pro Tour, their biggest event of the season. It’s not a

big secret that professional teams have done private data collection as

they prepared for Pro Tours. I’m not privy to that as I’m not a Pro Tour

player, but data is clearly an important part of their preparation. It’s

largely been secretive – which is certainly the right of those players who

have collected that data; I don’t want to be critical of that. I just think

everyone could benefit from more data. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve

heard people say, “I’m not going to buy into Standard right now; I’m

waiting for the Pro Tour when they break [the meta].” There’s a belief that

pros will secretly find something wildly powerful and bring it to the Pro

Tour and it will radically reshape the meta or they will “solve” the meta

and find the best deck.

I believe this is by and large a fallacy in the days where hundreds of

people are churning through cards and the meta is moving so fast,

especially in this Standard season. We have the people doing it already,

but we don’t have the data being shown. We don’t have to wait. We, the

masses, can shape the meta. In fact, we did: the MOCS event before Pro Tour Guilds of Ravnica was littered with aggressive Boros decks. When

they were highly represented in the Top 8, I wasn’t surprised; I knew they

were popular because I’m highly tuned into what is going on meta-wise from

Magic Online. Making data available to the public has a tremendous capacity

to level the playing field, especially for the competitors who aren’t

heavily enfranchised in the game.

Bryan

: Wizards of the Coast have seemingly taken a “less is more” approach when

it comes to data sharing. Do you ever wonder if efforts like yours – which

seem to be in direct opposition to their preferences – could potentially do

harm to the health of formats?

Matt

: I don’t think this is damaging for the health of the meta; I actually

feel the opposite way. I think more data makes for a better meta. When you

identify the best performing decks, you can also identify what decks

perform well against them and why. Players can move to those decks or

strategies which perform well. This probably takes a different form in

Standard versus Modern versus Legacy, as player enfranchisement differs. If

we call a format solved, that means that there was a serious flaw in the

design of the meta. Otherwise, I don’t think a format is ever truly solved;

metas should sift and churn as various strategies rise to the top only to

be unseated by their counter-strategies, who are then countered by other

strategies.

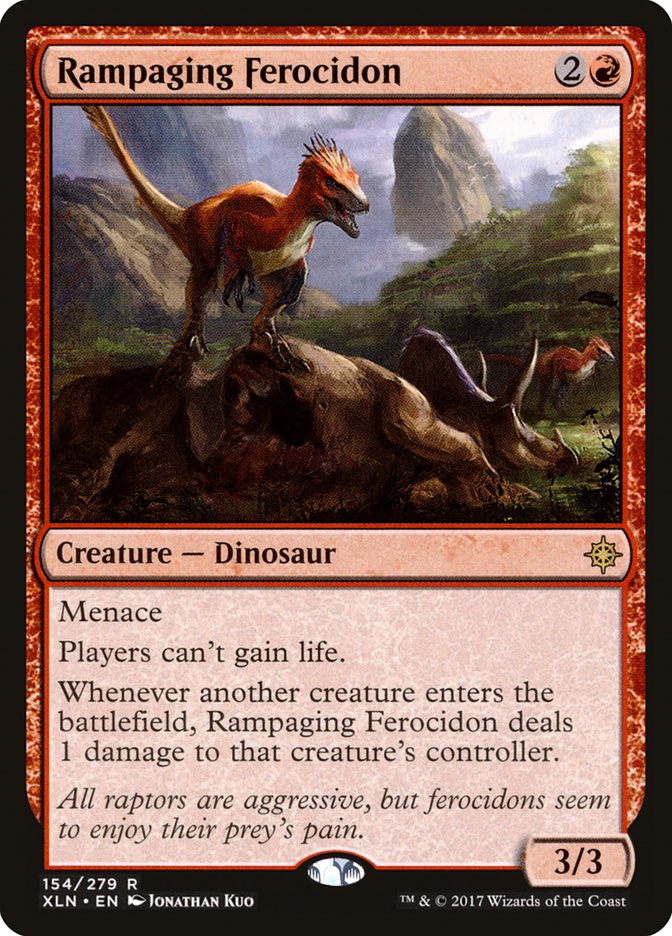

After the January bannings of Attune with Aether, Rogue Refiner, Rampaging

Ferocidon, and Ramunap Ruins, we saw some excellent data from internal

Wizards research showing the win rates of Temur Energy and Mono-Red versus

the format at large, along with excellent analysis of why they were making

the banning decisions they were. It was a good example of data-driven

decision-making, and at the time I was extremely impressed. Those bannings

made sense because by and large that format was solved: you played

Temur because it fared well enough against most things after sideboard or

you played Mono-Red to beat everything but Temur.

A year before, they had done a similar post on Aetherworks Marvel,

indicating that the mass player perception (that Marvel was suppressing

other strategies) was actually incorrect and that there were a number of

well-performing decks. It felt a bit backhanded, like they were banning

Marvel still, but the player outcry for a banning was flawed because the

data showed that Marvel wasn’t truly oppressive. If players were aware of

this, I think they would have had a different feeling about the format.

Data allows us to correct our biases. When someone activates Aetherworks

Marvel across the table and finds Ulamog, The Ceaseless Hunger, eats two of

your lands and you’ve effectively lost already, you’ll remember that more

than two other times someone did that and they missed. You’ll remember when

you lose. But data can help you correct those biases because it’s an

aggregate of player experiences. Data helps us discover what is

over-performing against the top decks in the meta. I guarantee more people

would have been on Esper Vehicles if people knew it posted a near 60% win

rate versus Aetherworks Marvel.

I want to make clear a caveat that data isn’t everything. I would argue

that Aetherworks Marvel or Emrakul, The Promised End were still poorly

designed, and subjectively, made for a bad play experience. But it matters

in a way that Wizards not only has avoided making public but have actively

worked to mostly prevent data from being available to the gaming public. I

can venture some theories as to why: maybe it was a lack of confidence in

Standard – especially at that time – and believing that it could be

“solved,” maybe they just don’t want the scrutiny, or maybe they feel that

data will make the game less fun. I don’t think any of those arguments hold

water, but I would love to dialogue with people who feel otherwise. I

personally think that the Play Design team has been incredibly positive and

impactful on the game. It’s been tangible how much Standard game play has

improved as they have been able to have an impact on the game. If anyone on

Play Design is reading: You all have done incredible, incredible work, and

I thank you as a player.

Bryan

: With regards to the specific data collected here, what do you identify as

its biggest flaw/potential inaccuracy?

Matt

: We definitely have a sampling bias. We collected approximately 45 percent

of the matches from GP Atlanta, but from a couple different places: the top

32, coverage, and then the player survey I launched. When we attempt to

draw conclusions from this and Bant Spirits has four decks in the top 32,

one of the things that emerges from the data is “Bant Spirits is a

high-performing deck.” Really? Wow, who would’ve guessed? So we’re missing

a lot of nuance, especially at the earlier levels. The player survey also

got more engagement from highly invested players, since I spread it through

Twitter and various other Discord servers.

Another serious flaw is that all things considered, even with 45% of the

meta in the room accounted for, this is a small sample size. It’s more data

points than your average social media shared article about side dishes

brought to Thanksgiving by region, but it is still small. So the ability to

draw definitive conclusions from it is limited. I would not treat this as

authoritative, but it does have some weight to it. Considering my lack of

background in data analysis, I’m sure there is a much bigger flaw that I

haven’t even thought of yet – maybe in the comments on this article,

someone can enlighten me.

Bryan

: What do you think is best way for players to use the information

contained in your report?

Matt

: The best ways to use this is with a grain of salt. The report that I

wrote up is my analysis of the trends I saw in the data and as a player who

plays and watches a lot of Modern, but it is my take on the format. Further

data collection might prove this analysis wrong. For example, as I’m

writing this, I’ve heard that two Golgari Midrange decks did well in one of

the Modern challenges, although I wrote that midrange black-based

strategies are poor to play right now. I still feel that way. It would be

neat to see what they played against in the Challenge to see where they

performed well. Data alone isn’t everything; a deck winning doesn’t tell

you everything about the deck or why it’s succeeding. You need to be able

to interpret data or offer an interpretation that makes sense. And of

course, data won’t gift you a win in your games because you’re playing the

objectively best deck.

I’ll be honest: part of what motivated me was personal interest. I’m

preparing for GP Portland and the December RPTQ, and I wanted to know what

was well-positioned going into those tournaments. But the ability to shift

decks isn’t common among the Modern player base. Most people are going to

stick to the deck they’ve put investment in. Now we know more about what

the winner’s metagame looks like, as well as those lower performing decks,

and you can adjust your sideboard – which has always been more impactful in

Modern – to more adequately reflect that. Maybe even your maindeck. For

example, if you read our report, you know that traditional builds of Jeskai

and Azorius Control strategies are bad thanks to the prevalence of Dredge.

You can solve that by maindecking Rest in Peace, and several people did

that the same weekend at GP Atlanta to success in the Magic Online PTQ. Is

Unmoored Ego what you need in a Grixis Death’s Shadow deck to beat Amulet

Titan? Is Infect actually bad against the combo heavy meta? Is Selesnya

Hexproof the third best deck in Modern? Maybe! We don’t know the answers to

these questions yet. I really hope Selesnya Hexproof isn’t the third best

deck in Modern, though.

Bryan

: What was the most surprising thing your data collection efforts revealed?

Matt

: Most of the data makes sense if you think about it for a little bit.

Ironworks performing well in the hands of some of the best players – yeah,

it’s going to post a high win rate. Little things are more surprising, like

Jund getting absolutely destroyed by Humans. By our data, the

matchup isn’t even close, which seems to run counter to the narrative of

Jund being a deck full of answers that takes apart creature-based decks.

TitanShift also performed well in the winner’s metagame, which is

surprising to me because there weren’t that many midrange or controlling

decks that TitanShift seems to do well against, but our data indicates it

is practically thriving, perhaps feasting on Dredge players. But the most

surprising thing, by our data, Jund also performed very well versus Dredge,

which seems counter-intuitive to how the matchup has been perceived. So is

that an accurate reflection of the matchup? Is Jund favored against Dredge?

These are questions I want to answer with more data.

your games because you’re playing the objectively best deck.

So, if you’re going to be playing in GP Portland, keep an eye out for

another player survey we’ll be sending out to collect your experience. Keep

track of what you play against; that’s incredibly useful in building our

matchup spreadsheets. And share your data with us so we can do another,

even better report on Modern. I’d like to take this opportunity to publicly

thank everyone who responded to the survey for GP Atlanta; this has felt

like a successful first venture, and it would not have been without their

help, so thank you so, so much. You are the three spells pre-combat beneath

our wings.

***

I left my conversation with Matt very impressed. He very clearly has a

vision for the future of Magic that is based on a much more empirical

model, and as efforts like those of his team pick up steam, competitive

Magic players will certainly have to jump on board or face being left

behind. I want to share some of my own thoughts based on the data contained

in this report. Again, I am not calling these conclusions. They are simply

theories which merit further consideration and exploration.

If More Players Pick Up Ironworks, Ban Talk Will Actually Be Justified for

Once

While I would be uncomfortable asserting this position from this data

alone, the fact is I’ve never seen one of these metagame analyses that

doesn’t present Ironworks as having an absurdly high win rate. In this set

of data, we’re looking at a 59.18% win rate across 98 matches. That’s

certainly high enough for me to stop and take notice.

Ironworks is held back by two things. First, players perceive it as

extremely difficult to play. Second, the deck is challenging to play on

Magic Online.

While I can’t refute the second point, I think the first point is somewhat

overstated. With an actual B-plan in sideboard games in Sai, Master

Thopterist, the number of resource restricted games you must play has

dramatically decreased. You can easily beat Rest in Peace and Stony Silence

in the absence of pressure. The initial composition and understanding of

loops may take a day or two worth of practice, but decks that are

proceeding in a linear fashion are going to have a lot more “math-based”

decision-making than “strategic” decision-making. Ironworks’ goals are

mostly singular: get permanents until you form a loop or an insurmountable

battlefield. Decks like Jund and Jeskai are routinely asking pilots for far

more, as they must continually adapt their gameplans to simultaneously

disrupt and pressure while lacking the “I win” button that so many other

Modern decks have.

If more players come to this realization, these absurd win rates are going

to start making absurd Top 8s that are absolutely littered with Ironworks

decks. The only reason this is not the present reality is the deck’s

miniscule adoption rate (2.28% in the present sample). My advice? Stop

making excuses, learn Ironworks, and be rewarded for it. Because soon it

may be too late.

Hardened Scales has not Only Completely Outmoded Affinity, It’s Also One of

the Best Decks in the Format

Speaking of math-based decision making, the hottest new king of combat math

is Hardened Scales. This deck has everything: giant Inkmoth Nexuses,

machine-gunning Walking Ballistas, human road cones, and the scariest

Arcbound Ravagers you’ve ever seen. This new version of Affinity is no

longer asking “hate or no?” and leaving its tournament results up to

matchup roulette. Matchups have mostly floated to the slightly favorable

range across the board, with a potential weakness to Humans being canceled

out by a strong Dredge matchup.

Again, I think Hardened Scales is being held back by difficulty fears, and

again, I think these are overstated. That’s not to suggest you will be able

to quickly pick up Hardened Scales and play optimally, but I think that’s

fine. The goal of optimal play should always be at the forefront of our

minds, but when decks are pushing absurd win rates we need to ask which is

better: a 45% deck played in a near optimal fashion or a 56.17% (across 162

matches) deck played at a slightly less optimal fashion?

Dredge Is Overhyped Due to Polarized Matchups

Dredge post-Creeping Chill has certainly improved and observed win rates

are among the best in the format (53.70% across 162 matches). However,

where Affinity has found a path away from the matchup roulette game, Dredge

is still caught in the same old quagmire. And honestly, much of the issue

comes down to respect. In the GP Atlanta data, we saw Dredge tearing

through Azorius Control, winning seven out of eight pairings.

But as the format has moved, we’ve already seen Azorius players “press F”

and shift the completely reasonable Rest in Peace to the maindeck.

Adaptations like this will degrade a highly favorable matchup quickly. I’d

argue that Jund came out of the gate at GP Atlanta having already made such

moves with maindeck Nihil Spellbombs and sideboard Leyline of the Void, and

we saw how things went for Dredge there (winning only five of fifteen

matches in what has long been thought of as a favorable matchup).

Decks will continue to make these low-cost moves, and Dredge will retreat

to a metagame call once more.

Linearity is King, But That’s Nothing New

Let’s look at the observed win rates for all the most popular “answer”

decks at GP Atlanta.

- Grixis Shadow- 48.54%

- Mardu Pyromancer- 46.84%

- Jund- 46.24%

- Golgari Midrange- 45.00%

- Jeskai Control- 44.68%

- Azorius Control- 42.51%

These decks are not cherry-picked examples of answer decks that did poorly

in this analysis. Among the Top 20 most played decks, these are all the decks that can be reasonably regarded as falling on the

“answer/midrange/control” side of the spectrum.

The correct approach to Modern at almost all points since its inception has

been to find the best deck that ignores your opponent for a given metagame.

I think you can argue there was a moment where Jund with Deathrite Shaman

turned this on its head and, depending on how you want to classify Birthing

Pod, I would listen to arguments about its place in this discussion as

well. But much of Modern’s history has been a shuffle from one hyper-linear

approach to another. Whether you want more from Modern or you love it just

the way it is, it behooves you to recognize this key takeaway. Think about

what the format is holistically vulnerable to and find the linear deck that

pushes those buttons.

Or, find the linear deck with a powerful B-plan that resists hate and might

just be broken. Any decks pop to mind?