Cube ain’t what it used to be.

This time last year, the most anyone could hope for in a Cube tournament was win some treasure chests and maybe a couple of MOCS qualifier points on Magic Online. This year, SCG CON Winter is going to host the highest-stakes Cube tournament of all time.

With over $10,000 in prizes between the $10,000 Cube Draft and the qualifying tournaments that feed it, there’s a severe lack of content surrounding the Cube itself and how to actually take home the gold in the tournament. As a tournament grinder, content creator, and playtester for the Cube, I find myself at a unique intersection.

Without pulling the curtain back too far, the actual design process for this Cube was process-oriented in such a way that both the draft experience and the gameplay is engineered to end up in a place that creates great games to watch as well as play. The part that I played specifically was drafting different decks, playing them several times, and completing evaluations of each iteration of the Cube, looking at what played well, what ruined games, what made games more memorable, and what cards should be added or removed to the Cube. It wasn’t easy to grasp some of the concepts at first, and there are a handful of things with this Cube that are very different from the Vintage Cube that Magic Online has acclimated so many of us to.

360 VS. 540

Rather than being a 540-card Cube, Star City Games elected to go with a 360-card Cube, guaranteeing that we’ll have the chance to see all of the Power in action, as well as lowering the odds that some of the more synergy-driven decks that people tend to draft have to make do without their more powerful payoff cards. This effect ripples throughout the rest of the archetypes in a way that isn’t obvious at first, but makes more sense once explained.

Reducing the odds that the synergy-driven decks don’t find their payoff card creates a situation in which those decks end up becoming much more powerful, as Reanimator is near-guaranteed to see Reanimate, Opposition decks find their namesake, and so forth. On the other side of things, the fair decks, more specifically, the low-to-the-ground aggressive creature decks, end up not gaining as much in this exchange. Why?

Most aggro decks in Cube don’t lean on the power of their cards but redundancy. Sure, Kytheon, Hero of Akros is a more powerful card than Dauntless Bodyguard, but the marginal gain Mono-White Aggro gets from Kytheon over Bodyguard isn’t nearly as high as, say, Reanimator being positive that it’s going to see Entomb instead of Buried Alive.

This relationship with power-level spikes led to a situation that involved some of the more powerful synergy-driven decks being powered down in order to allow creature decks to survive at all. Without this happening, it was near-impossible to play anything white and aggressive without just getting laughed out of the room.

For a bit of anecdotal evidence, in an earlier week of playtesting, I had an Orzhov Aggro deck with great mana, splashing black for Kitesail Freebooter and Mind Twist, put up an 0-3 record despite Mind Twisting my opponent’s hands at least once per round while I had four or more power on the table. Getting topdecked out because all of your opponent’s cards are just that much more powerful than anything in your deck is a horrid feeling, and the route that Justin Parnell (the lead designer of the Cube, who wrote a great article about it here) elected to take made for a much better play experience overall.

Without this understanding of how the decks have been balanced against one another, an easy trap to fall into is being under the assumption that the aggro decks look much better than they truly are.

Taking and applying this to the drafting portion of the tournament, let’s take a look at the decks that are firmly represented in the Cube:

White/X Aggro

The most natural place to start is by breaking down the aggressive creature deck we’ve worked so hard to make playable in this Cube. The most powerful cards in this deck are easily Mother of Runes, Stoneforge Mystic, and the Armageddon effects.

When drafting any archetype, understanding what is most likely to table, and what won’t make it back to you, is one of the most important skills to hone, and it’s pretty easy to figure out whether a card is going to make it around or not when drafting the white decks. When looking at a couple of cards against each other, ask yourself, “How many decks is this going to fit into?” The more decks something plays in, the less likely it is to wheel.

Take something like Blade Splicer, for example.

Blade Splicer is the type of card that is very good at attacking, yet will also end up in the white midrange and control decks because it’s so strong on defense. This means that, while drafting as the white aggro player, you must value these sorts of cards higher in your pick order than something more linear like Toolcraft Exemplar.

When trying to pair white with another color, there isn’t necessarily a “wrong” color, but recognizing the strengths to each pair is important.

Splashing blue will have a ton of upside because of the power level of the blue spells, but there’s a pretty big drawback when trying to build this deck: the mana is tough.

Mana fixing is at its most important in aggro decks, because these decks need to curve. Casting spells on time is the difference between killing the opponent right before they can stabilize and giving them just enough time to turn the corner. Blue being the most popular color is going to put its lands at a premium, and it will be harder to pick up Celestial Colonnade than something like Shambling Vents.

The risk can be high, but sometimes you’re drafting your white cards and you come across a Time Walk and shaky mana is worth the commitment.

The base-white Selesnya deck is more of an aggressive midrange deck than a pure aggro deck, trading some of its speed for power, with the biggest upside being that it gets access to several copies of an effect that’s frequently undervalued in this Cube:

Maindeck your Shatters. Just do it. With this being a 360-card Cube, it’s guaranteed that the table will have access to almost all the Signets, all the Moxen, Sol Ring, Mana Vault, all the Stoneforge Equipment, fast mana, big creatures, and more. You will have targets 80% of the time, and if they have literally zero things in their deck that can be hit with this subsection of cards, you can simply sideboard them out.

You’ve made it this far in the article, so there’s a level of assumed trust that you, the reader, are placing in me. Take that trust in place it in me when I say that there will be two or fewer drafters at the table with fewer than three artifacts in their deck, and these effects are much better than they are anywhere else.

Most of the black cards that play well in this deck tend to either give the deck a disruptive angle or play to a go-wide strategy. The best recommendation I have is figure out if you’re trying to be an Orzhov deck or a Mardu Sacrifice deck that I’ll touch more on later. If the goal is to simply be the Orzhov Aggro deck, lean a bit more into the disruption, as those cards are less likely to be cannibalized than the go-wide strategy cards, as the Mardu deck is also interested in Sorin, Solemn Visitor, Lingering Souls, and so forth.

The Orzhov deck has the lowest upside for the weakened mana, and for the most part, I’d recommend looking into the aforementioned Aristocrats-esque deck, but I’ll touch more on that shortly.

Adding red cards to white aggro is incredibly attractive in a vacuum, as it gives the deck some much-needed reach and red has a ton of cards that play well in a low-to-the-ground aggro deck.

In reality, it can result in situations where the drafter trying to build Mono-Red Aggro ends up getting ruined by the Mono-White Aggro drafter and vice versa. Adding one or two red cards to the deck is perfectly reasonable, but leaning into making it a two-color deck is playing with fire, as the fixing isn’t a given, and if the red player also leans into the way that red and white complement each other, it could result in neither player having a reasonable deck.

Mardu Sacrifice

This is one of the more “secret” archetypes that may not be as apparent at a glance, but it’s quite real. The trick to drafting this particular style of deck is looking for the cards that are powerful in a generic sense, and then taking the archetype specific cards as they go late. The basic idea is that the deck is very good at producing a ton of expendable and/or recursive bodies and then having payoffs for sacrificing them. Take the following decklist for example:

Creatures (14)

- 1 Dark Confidant

- 1 Mogg War Marshal

- 1 Shriekmaw

- 1 Bloodghast

- 1 Blood Artist

- 1 Ophiomancer

- 1 Pia and Kiran Nalaar

- 1 Hangarback Walker

- 1 Zulaport Cutthroat

- 1 Bomat Courier

- 1 Kari Zev, Skyship Raider

- 1 Legion Warboss

- 1 Goblin Cratermaker

- 1 Plaguecrafter

Planeswalkers (1)

Lands (17)

Spells (8)

A deck incredibly similar to this ended up being fairly successful in multiple playtesting sessions, and it isn’t something to be discounted, but using this list as a stencil, it’s fairly easy to break it down into parts. There are the cards that stick out as easy first picks from each pack:

Cards that are fought over and would’ve been taken early:

…and finally the archetype-specific cards that nobody else would’ve taken unless they’re also trying to build Mardu Sacrifice:

Not everything always fits into these boxes, but it’s a good mental frame for how to draft synergy-driven decks. The exceptions to these rules are decks that live or die by their archetype-specific cards.

Opposition

Opposition is a deck that can function without the card Opposition, but the difference between games with and without the card is night and day. Taking this into account, anybody drafting the Opposition deck is going to slam that card as soon as they see it. The deck itself is effectively a green-based Simic deck that has a handful of blue cards that play well with having a ton of mana and/or a ton of do-nothing creatures.

In contrast with the Mono-Green deck, Opposition tends to rely more on its creatures, as the blue cards it plays are so much better on earlier turns of the game and having a bunch of excess mana for something like Upheaval will translate to having more things on the battlefield after Upheaval resolves.

On that note….

Mono-Green

Mono-Green cares about its creatures, but without the same draw power or prison elements that the Simic deck has, Green needs a higher density of things to do with its mana and can’t find as much to do with its excess creatures. This creates situations where some quantity of ramp will be nice, but it isn’t uncommon to leave some of the weaker ramp options on the side.

One thing to be cognizant of while drafting with the Mono-Green deck is that its payoff cards aren’t necessarily safe from other drafters. Reanimator players are happy to pick up Hornet Queen and Woodfall Primus, fair green decks love the easily cast Thragtusk, and so on.

Rec-Sur

Short for Recurring Nightmare plus Survival of the Fittest, this is one of the archetypes that makes fitting all of the Mardu Sacrifice cards in the Cube possible. Both Survival of the Fittest and Recurring Nightmare are fantastic cards on their own, but in a value-based Golgari creature deck, they’re pushed far over the top.

This deck is interested in the black token producers (Ophiomancer specifically is a house) and as many green value creatures as a single deck can hold.

A trap that everybody falls into once is that, with Recurring Nightmare, it’s important not to take all the creatures out of your graveyard. Sacrificing tokens to recur cardboard is a nice feeling, but the value attached to creatures being looped is worth more than the single extra creature that would be upgrading a token, so don’t get too greedy in a single turn. Make sure there’s always something to dredge up.

Reanimator

This deck is rarely going to be mono-black, but there are draws to every color combination. The draws to each are related to how fair the deck is interested in being.

The Rec-Sur deck is actually a reasonable shell for Reanimator, depending on whether it’s base-green or base-black, but the gist is that black is very good at putting things in the graveyard and then taking them back out of the graveyard for less mana than Wizards of the Coast intended.

The cards that red can add to the Reanimator strategy hardly scream fair, with Hazoret the Fervent even working as both a payoff for having discard outlets and a discard outlet herself.

Blue is the best at exchanging explosiveness for consistency in its iteration of the deck. The Scarab God and Champion of Wits were both recently in a Standard midrange-them-out deck, so it doesn’t feel as if there’s much explanation necessary here.

The important thing to note is that the Reanimator deck’s discard outlets tend to involve drawing cards as well. This is an easy thing to notice, but the next leap to make is that it isn’t particularly difficult to end up in a three-color Reanimator deck, as the Rec-Sur deck will have green for fixing, and the other two colors get to see so many cards in their deck that finding three colors of mana is going to be fairly academic, assuming that the deck’s manabase isn’t just absolutely atrocious.

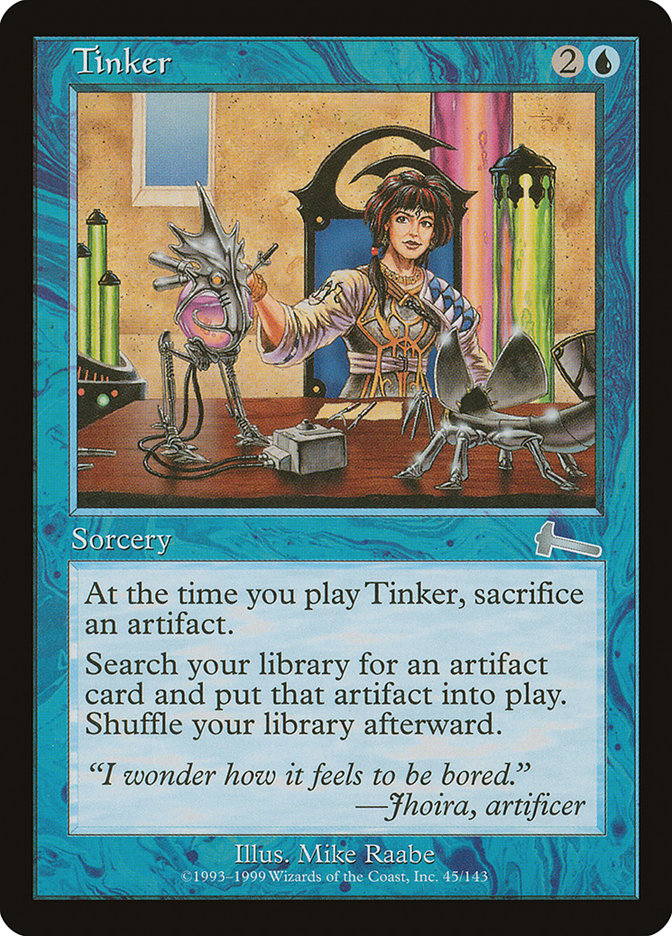

Tinker

Artifacts are so good in this format that it’s incredibly easy to have the enablers for the Tinker deck. The issue is finding the payoff cards. Here they are:

That’s it.

Without Storm in the Cube, there isn’t much reason for Memory Jar nonsense, and Blightsteel Colossus creates so many non-games that it wasn’t included. This means that whoever opens a Tinker needs to value these two cards over almost anything else, assuming they want to play Tinker in their deck.

My advice is that Myr Battlesphere is generally better than Sundering Titan, and is also taken higher, as it’s a fine Reanimator target and something that the Opposition decks are happy to play. The Sundering Titan might wheel, but your mileage may vary in this department. Realistically, if you have the Tinker and you see either of these cards, you need to take them.

As far as what else to put in the Tinker deck, there isn’t really a deck that’s solely dedicated to Tinker itself, but the best shell for that is an Izzet Artifact deck that isn’t as obvious at a glance as one would assume.

With a ton of Islands in the deck, Vedalken Shackles starts to enter the realm of “cards that aren’t completely embarrassing to find with Tinker.” Smokestack is another card in this universe.

Playing Tinker means playing a ton of things that can be sacrificed early. For the most part, this translates to mana rocks, which play well with mass land destruction effects, and the cards at the top of red’s curve are more splashable than the cards at the top of white’s curve. Mono-Red Aggro also isn’t interested in these cards, where Mono-White Aggro is interested in Armageddon and friends.

This isn’t even getting into the cool synergies that come with Dack Fayden and Pia and Kiran Nalaar.

Mono-Red Aggro

Similar to Mono-White Aggro, the red deck may look unreasonable on paper compared to everything else, yet in reality is quite balanced. There isn’t anything particularly fancy going on here, but there’s certainly an underlying tension with the cards that the mono-red deck wants to play and other decks want for what they’re doing, and this tension may not be obvious. For example:

I mentioned before, but Hazoret also plays in the Reanimator deck and may not table in the way that one would assume.

Very good in the Mardu Sacrifice deck.

Remember that a fair chunk of the cards that play in the aggressively slanted red deck are also going to work as defensive and grindy tools for the midrange decks that crop up in Cube. Even if these cards aren’t quite as important as something like Fireblast, it’s almost a given that Fireblast will table, but these are much less likely to do so.

Cryptic Command

Despite being a great card, Cryptic Command is pretty hard to fit in anything that isn’t a blue deck that wants to play several turns of Magic. This makes it easy to define the blue control decks as “Cryptic Command piles,” as even the other decks with blue are going to have a hard time ever casting the card, what with its three blue pips and all.

Realistically, these decks are just going to be “U/X Good Stuff,” and that means having a bunch of fixing and a bunch of powerful cards. White is the color that meshes the best with this archetype, as the handful of sweepers translates to a bunch of cards that catch up on the battlefield, and the counterspells make it hard to develop on the table once the blue deck has established its manabase.

Drafting this deck is fairly intuitive, as it’s just taking the most powerful card in each pack, but as a quick aside:

However good you think this card it, it’s better. In our final rankings of the most powerful and swingy cards in the Cube, I put this around tenth place. I may have been a bit hyperbolic at the time, but Vintage Cube has so many powerful cards that simultaneously answering their most powerful card and creating a copy for yourself is generally going to be worth far more than the single plus-one it generates in terms of card advantage.

Closing Notes

That covers most of the decks that were fleshed out during the designing of the Cube, and anything I missed is likely a variant of another deck that’s listed above. These aren’t the only things that are doable and some of them can even work as packages in other decks entirely. This is meant as a guide to help people who are newer to Cubing or want to understand the theory behind it a little better.

The last thing worth noting is that the creatures that work as incidental hate cards are all super-reasonable. Tinker and Fastbond are both unfair, but they’re about as unfair as things get with this Cube. There aren’t any fast “You Lose” buttons in the vein of Tendrils of Agony or Splinter Twin, so building with midrange games in mind is going to reward you far more often than anti-combo will, so creatures that cover your combo bases should be welcome additions to your decks.

If you want more Cube support in the future from us, please leave feedback. These kinds of events are fantastic and knowing how much people love them is what helps motivate us to make it happen in the future.