I still don’t know anything about current Standard, but what I have been doing lately is working with a new team, and I think I’ve figured out how to work with people substantially more effectively. You don’t need a super team or the best players in the world to learn a lot more from the people you play with. What you need is to find people who are interested in putting time into sharing ideas and build an infrastructure for doing so. Today, I’d like to discuss building that infrastructure.

Learning from others is fundamentally about learning. In order to actively learn, you’ll probably want to start by accepting that you have things to learn, and in order to learn from others, you’ll want to believe that they have something to teach you. It’s easy for egos to get in the way of learning from others. One hack to get around this is to realize that someone doesn’t need to have to be better or smarter than you are in order to teach you something. Magic players are often taught that the best way to improve is to find people who are better than them to work with and play against. This may be true, but even if you’re the best player in your area or the best player you know, you can still learn from people around you.

I don’t often cite quotes, but I was reminded yesterday about this one: “Who is wise? He who learns from everyone.” It’s important to trust that anyone might have something to teach you if you listen, but to me this quote can be taken two ways, both accurate. Wisdom comes from learning from everyone, but at the same time, wisdom is required in order to learn from everyone. This requires the ability to distinguish good ideas from bad ideas. As long as you can do that, you should hear whatever anyone has to say and can take any nuggets of wisdom you encounter and learn from them – but if you don’t know enough to distinguish good ideas from bad ideas, you need to be sure to only try to learn from people who are better than you are so that you don’t follow bad advice.

Personally, I think it’s best to try to take all the advice and learn how to distinguish the good from the bad rather than to try to restrict your search to finding only good advice.

So what can someone who you are better at Magic than teach you about Magic, and how can you learn it from them? For the most part, you’re not going to want to ask a worse player about fundamentals and figure out what specialized knowledge they have. Everyone has different knowledge about Magic from their own experiences, and anyone who plays a lot should have a lot of experience. A weak player who always plays the same deck will still likely be able to tell you something you don’t know about that deck. Knowing that you’re better at Magic, they’ll have no idea what to tell you about it though, because they have no way of knowing what you don’t already know… so you need to know how to ask the right questions.

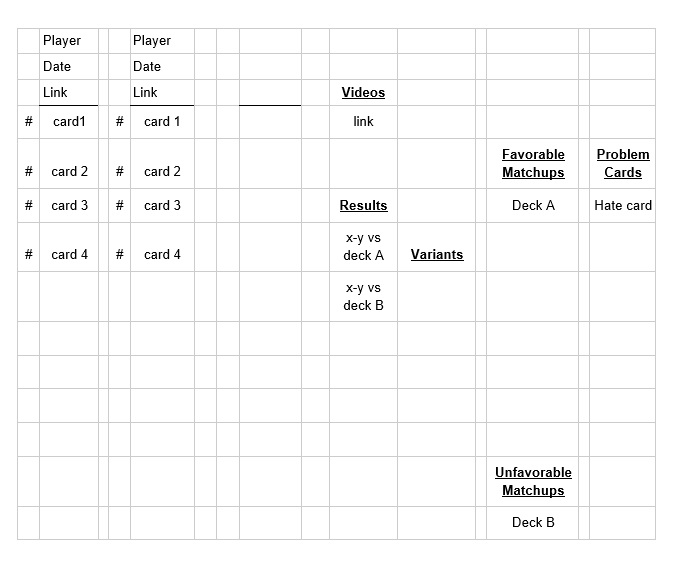

The most important innovations that my new team has used have been spreadsheets created by my housemate, Justin Cohen, who is about to play in his first Pro Tour. He’s been using spreadsheets to analyze formats for a while now, and he’s gotten pretty good at it. For Modern, he set up a page that looked like this:

He created a spreadsheet with a separate tab for each archetype in Modern and populated each page with recent lists he found online, including a link to where the deck came from and any articles written about the deck. Then he shared the sheet with the team so that anyone could add their versions of each deck to the sheet for the archetype. If multiple players had builds of the same decks, it was easy to cross-reference and see how the decks differed. Whenever people tested, they could enter their results of the testing session into the results column, and whenever you looked at a deck you could immediately see what differences existed in different card choices and what results we obtained with the deck. This made it much easier to keep everyone on the same page.

This makes it easy for weaker players to share their specific information, though of course, you might want to be careful about giving too much credit to their results. Highlighting differences in different lists can easily facilitate discussion.

That discussion was hosted simultaneously in a Facebook group. I know different players have strong preferences about using mailing lists versus message boards versus Facebook groups to organize teams or testing groups. Personally, I strongly prefer Facebook groups. I think email is a little too invasive. Having everyone get an email every time someone wants to answer a quick question about a deck makes answering or asking such a question seem like something you should be careful about choosing when to do, but the bar to comment on a Facebook thread is lower and this helps keep people communicating. Also, depending on how you have your inbox set up, sorting through discussions on different threads on Facebook can be quite a bit easier than tracking through which conversation in a string of emails a particular message is a part of. I prefer Facebook to another message board because I was going to be checking Facebook anyway, so I don’t have to add checking a new place to my routine, and I’m much more likely to see a new post on Facebook much more quickly than I would on a dedicated message board.

As for Limited, I’ve really struggled in the past with finding good methods for sharing information. The Pantheon always had a long meeting where we talked through our thoughts on the Limited format, and some of those conversations had been recorded and made public back when we were Team StarCityGames, but this has always been a single conversation days before the Pro Tour. Before that, strategy would be shared through random conversations during a draft with opponents or spectators, but nothing organized. Eventually, I took to gathering a stack of all the commons and uncommons in the set, handing them out to people so they could organize them by how much they liked them, then entered those rankings into a spreadsheet so that we could talk about them. I liked that, but I think it’s just the beginning.

Justin has gone much deeper. He ranked the commons and uncommons by color, then the top commons and uncommons regardless of color, then we separately ranked the rares by whether or not they should be taken over the top commons and uncommons – there’s no reason to compare them to each other because it’s not possible to open a pack with two rares at the Pro Tour because foils are replaced with random commons. The entire team would then meet in a Google Hangout to discuss the rankings to see if anyone disagreed with anything and talk through where people had different experiences. This was all basically what I’d done before.

Justin’s spreadsheets also include a page of lists of every instant in the format sorted by color so that he can reference it while playing on Magic Online to know what tricks his opponent might have. This helps gets him in the habit of knowing every spell that’s available to his opponent at all times, and he has made a similar list for all the removal in the format.

Where we’ve gone the deepest is the last page, which is a series of deck sketches. These are lists of seventeen spells organized on a spreadsheet the way that one would lay out a draft deck – everything sorted by casting cost and with creatures kept separately from non-creatures. These are pauper highlander skeletons of archetypes you can expect to draft. What that means is that they’re lists of roughly what you can expect a draft deck to end up looking like assuming you have access to one of each common, and then you get to fill in the last five to seven cards with uncommons and rares you happen to see. The purpose of this exercise is to see how much support there is for each archetype and what their curve might look like. This can help when you find yourself choosing which two- or four-mana creatures to include and which to cut, helping you realize during a draft that unless you’re short on cards at that cost, any card that didn’t make it into your deck skeleton is unlikely to make your draft deck – you can pass it and expect to see one of the other commons you’d rather have in that role.

This can lead to a lot of interesting realizations about the format. As an example, for me personally it helped me to realize how often I don’t really want Arrow Storm, a card I generally think is powerful but have trouble fitting into decks because I’m trying to keep my curve low and my creature count high and it works against both of those goals. Making multiple decks in a single color pair or clan can show you how capable the card pool is of supporting decks that go in different directions. If you can’t make a list of seventeen commons that looks like the start of a reasonable deck, you can expect that you probably won’t be able to make that archetype work in a draft.

This can also facilitate discussion about cards the same way that building a draft deck with teammates after drafting can. We might include a card in a sketch for how we think blue-red aggro should look only to find that other people think the card isn’t very good and we probably shouldn’t be looking to include it, or we might leave something out that other people have had great experiences with, presenting the opportunity to debate why we’ve made the decisions we have.

This allows us to approach Limited strategy and deckbuilding in a way that’s much more akin to Constructed deckbuilding, something we already know how to discuss.

Again, when discussing Limited, I’ve found it very easy to fall into the trap of finding people thinking, “Well we already know how to draft” and just evaluating the new cards to make sure that no one is far off on any specific card. I think it’s best to realize that you could be doing something wrong on any level and find ways to broaden the conversation. I think finding ways to talk more holistically about where you’re trying to end up can do that, and the next part is figuring out how to get there.

Working with a team consisting of members from all over who can’t readily meet in person has been a new challenge for me, but being able to continue testing in person with my teammates who live near me has helped with getting the kind of preparation I need and I think this team has done a lot to improve communication in the face of these geographic and logistical obstacles. Necessity leads to invention as always, but I hope that I’m able to carry over these innovations to help communication even when I’m working with a group in person, and I think organizing a spreadsheet even for a local group can provide an extremely powerful tool.