Lots of people complain about how land variance is the “worst part of Magic,” but really it’s one of the best. Much like how all the decisions you make pre-event are often ignored when talking about play skill, the decisions you make in your manabase have wide-reaching effects most players ignore because it’s “just lands.” The cards you can cast, how your deck plays out from game to game, and how it operates when faced with different strategies all flow from something as simple as the lands you chose to play.

Color Requirements

This is the obvious one. Sometimes your cards are hard to cast unless you draw specific land combinations.

The reward is power. Your spell costs BBBB instead of 3B for a reason. You might draw an extra land per game, but your cards carry more weight in exchange.

This was a failure mode of the B/R Vampires decks early in the Standard format. You had Drana, Liberator of Malakir on one side, Thunderbreak Regent and Exquisite Firecraft on the other. You had card power, but you had to play more lands than you wanted to in order to make BB and RR. Those specific cards were good, but not good enough to balance out flood, especially when the rest of the deck pulled them down.

Color requirements surface in Limited in formats where there are big payoffs for adding a third or fourth color to your deck but the mana is only barely there. If you have two copies of Oblivion Strike in a G/W Draft deck, you might want to add a land to have enough sources for them, but there isn’t as much splashable top-notch removal these days. In a multi-colored format where the fixing was slow and not great at common, the eighteenth land makes a big difference in decks where you were stretched thin. Constructed has similar situations, such as old-school Bloodbraid Elf Jund getting better as you added lands because your spells were so absurd if you could just cast them.

Takeaway: The more specific colors you need to cast your spells, the more lands you should play. In Limited, this means pushing up to eighteen lands when splashing or light on fixing. In Constructed, this usually means 25 to 26 lands in midrange and a solid 27 in control when your mana is really tight.

Exception 1: If your spells have very specific color requirements but aren’t powerful enough to overcome flood, consider playing fewer colors. If your lands all make white mana to start, your double-white three-drop is basically colorless.

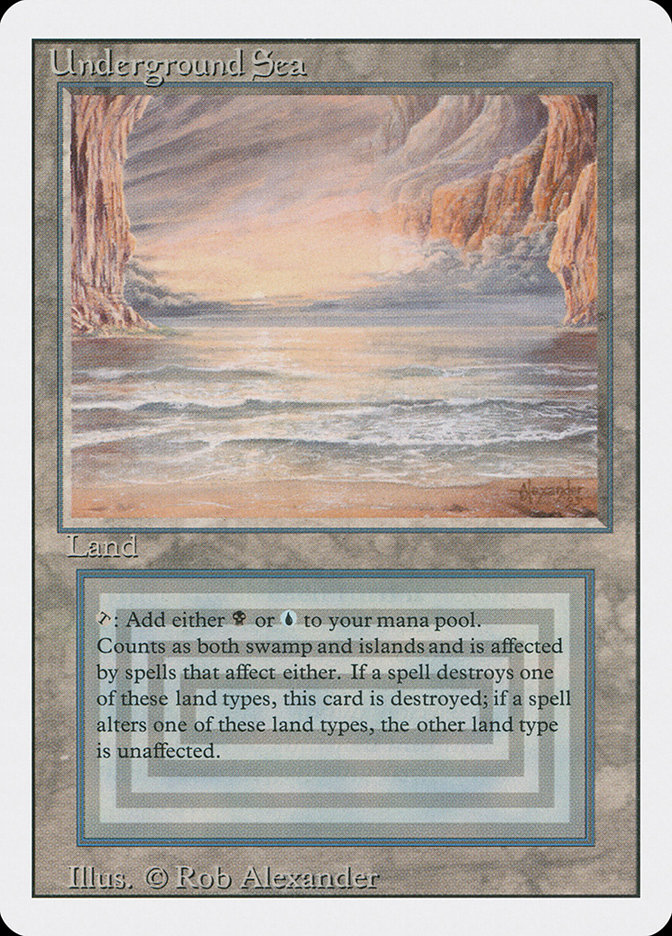

Exception 2: This all centers on the mana requirements actually being a bottleneck. If your lands all enter the battlefield untapped and make whatever colors you want, who cares. Your spells are again practically colorless.

Return on Investment

You spend a card to put a land on the battlefield. After that, it just makes mana. Is there any way to get more out of it than that?

In Constructed, whenever you have a land that provides around a spell’s worth of value that you get to easily play, you should immediately be upping your land count to adjust. Whenever you build a deck in the current Standard format that can support the Battle for Zendikar creature-lands, ask if you could possibly want another land. With four Lumbering Falls in your 26-land deck, it will often play as if you only had 23 lands for flood purposes and as if you have 26 for shortages.

In Limited, whenever you have an effect in the format that adds value to a mana source, it is going to be very powerful. Ravnica bouncelands like Simic Growth Chamber were borderline first-pickable because they were a single land that made two mana, and there was a point where I thought Traumatic Visions was the best common in Conflux. While these aren’t perfect examples, as the end result of them was not “play more lands,” they show the power of getting something out of your mana.

A better example might be a creature that makes mana. If the body associated with the creature is worth a card, that’s how you get to slot in a free mana source. A lot of people are immediately attracted to the ramp aspect of these cards, but smoothing out low land draws is just as much of a point in their favor.

The trap here is that often the value is false value. If the effect is so expensive that you can’t reasonably use it, you aren’t getting anything out of it the same way that an overcosted spell wouldn’t make your deck. Blighted Cataract looked like an insane card at first glance, but not paying you back on your investment until you hit seven total mana was too slow.

Similarly, if the effect isn’t worth the card or the marginal cost associated with it, it won’t help. The original Zendikar common “enters the battlefield” lands were the textbook example of this, and even some of the Battle for Zendikar ones like Soaring Seacliff and Sandstone Bridge were close to the borderline here. Similarly to mana creatures, if the body isn’t actually worth a card, you are just playing a land that costs mana to cast and not a real spell-land hybrid.

False value only applies if there is a cost. Sometimes it is an obvious non-cost, but it’s always a payoff versus cost question. Entering the battlefield tapped is not worth one point of life with Piranha Marsh, but it might be worth two damage with Teetering Peaks. Context also applies: Mutavault was absurd in a format with big payoffs like devotion for staying conservative on mana, but in Khans of Tarkir Standard, Mutavault would have struggled to compete with color-heavy payoffs like Mantis Rider and Siege Rhino.

Cost here also has a lot of implications of value over replacement. In Theros Standard, many decks would have played any two-color land they got. The fact the Temples provided the small value of a scry on top of fixing was absurd, and in turn decks got to play one or two extra lands because of it.

Takeaway: Lands that double as decent spells are great and let you overload on mana sources. Really good “value lands” push you towards the 26-land range in midrange and 27 in control.

Exception 1: Don’t get tricked into playing lands that look like they provide value but pay back less than the built-in cost of making colorless or entering the battlefield tapped.

Exception 2: If the land is more than a card of value because it produces two mana, it allows you to cut lands. Drawing Ancient Tomb and Island makes as much mana as three Islands. This is almost strictly a Constructed scenario, barring bouncelands.

Exception 3: Is there a mechanic that pays you for having extra lands? It can be any way to convert extra lands to spells. Landfall is the super-obvious one here, as it directly makes your cards better for having more land. The discard outlets in Shadows over Innistrad are a little weak or too rare to really pay off here, but in formats with common Merfolk Looter or other similar discard outlets, eighteen lands can be right.

Value Per Spell and Cantrips

Cards that give you more than a single card in return let you win through mana flood and therefore play more lands. There are, however, times where certain card draw effects push down land counts.

This really is one of the trickier aspects of land counts. How do you determine whether a spell that draws a card makes you want more or less land if there are examples in both directions?

One pointer towards the card making you want more land is if it is bonus value for bonus mana. If you are steadily going up in card count, you need ways to utilize your extra cards drawn before dying, and if your spells all get better with more mana, then you can afford to play more lands.

If the card is selection over quantity, that leans towards the “fewer lands” side. This is pretty simple. You build your deck to hit a specific number of lands and then draw as many spells as possible after that. Selection helps you in both directions and lets you cheat on your counts to ensure this.

Another push towards fewer lands is if the effect of your cantrip is not actually worth a card on its own. This is an extension of the classic “virtual 56 cards” scenario with Gitaxian Probe and Street Wraith. Your low-impact cantrip is more or less not in the deck when you are calculating odds of drawing a specific card type as it cycles through.

Too many low-impact cantrips can be a bad thing. This was a failure mode of U/R Surge in Oath of the Gatewatch Draft. If you are all low-impact cantrips without selection, your deck eventually draws into a hand full of land. You could cut lands to reduce the odds of this, but then you have to keep opening hands with one land, which wasn’t possible. In Constructed it is more doable, but people fell into the same trap with Delve and Thought Scour. If you go cantrip-heavy, you need to commit to being land-light.

Another factor is how much mana you are using on the effect. Two-for-ones are generally costed higher, selection a bit lower. An expensive but playable selection spell might not actually reduce the land count you need, and a cheap enough pure card draw spell actually will push your land count down. Imagine comparing “one mana, draw two” to Sleight of Hand. Both times you get the card you want, but this one comes with a bonus.

This is one spot where people get into trouble in the Shadows over Innistrad Limited format. In Shadows over Innistrad they see Thraben Inspector and Jace’s Scrutiny as reasons to play sixteen lands. They almost look exactly like low-cost cantrips. Clues are mana sinks, however, which pushes towards more lands. I would rather just not play too many of my lower-impact cards and keep my land count up. Multiples aren’t bad, but having tons is a problem.

If this seems less helpful and more case-by-case than the other tips here, that’s because it is. The general patterns are much more prone to exception here because, depending on the format and specific cards, the effect of going up a card might matter more or less.

Takeaway: Cheap cantrips that aren’t two-for-ones push towards lower land counts. “Draw-two”s push towards higher land counts. This is very much a guideline and not a hard rule, so if it ends up feeling wrong in a spot, it might be right to go the other way.

Playing on a Mana Budget / Pay More to Win / Timing Is of the Essence

There are a lot of things here, but they focus on the same core concepts.

You find yourself short a land in a game. Are you very behind or do you have plays that matter?

What is the lowest number of lands you can reasonably play a game with?

How much better is your spell one mana up than what you are working with now?

More than anything else, this is why Limited decks bias toward seventeen lands and not sixteen. If you look at the commons and uncommons that make up most Limited decks, they scale very sharply with cost. Missing your fourth land drop for a while means you’ll be facing down cards that drastically outclass the three-drops you are casting. It’s not insurmountable, but it does usually put you into a scrappy defensive role.

There are specific hyper-aggressive decks and formats where this isn’t true and fifteen or sixteen lands can be right. The W/R decks in Shadows over Innistrad are full of weak beaters, so drawing the extra spell for an extra attacker is relevant damage. The deck from the past that exemplifies this the most was the Intimidator Initiate mono-red deck in Shadowmoor Draft, which was basically a Constructed Mono-Red Aggro deck.

The Shadowmoor red deck played five=drops most of the time. It just didn’t play five-drops it had to cast on turn 5. If you get in for a bunch of damage early, your opponent is going to have to leave back blockers, and Traitor’s Roar is going to be just as good if the game takes until turn 8. Any Lava Axe effect is going to be similar.

For creatures, the equivalent is also true. An evasive creature is going to still close out the game if you hit your fourth land on turn 6, but something that is good for its bulky body is going to get much worse after things bog down.

Morph is a specific mechanic that pushed higher land counts, especially with the high morph costs of Khans of Tarkir. Missing your three-drop was game ending, as your opponent always had one, and then missing the morph turn on five was just as big. Anything else that creates a consistent curve slot will have a similar effect.

In Constructed, things are different. It isn’t a matter of average on-curve drops like it is in Limited, as you can select your cards. The best three-drop is probably a bit worse than the best four-drop on average, but it’s much easier for setup and surrounding cast to make up for that. You don’t absolutely have to curve out all the way in every deck.

What does matter is how well you play when you are stuck a land or two behind where you want to be. Do you have cheap effects that let you fight to extend the game to the point you want to reach, or do your spells not let you play small-ball?

Just as much as playing the low end of the game, what your big game accomplishes matters too. Are they going to end the game regardless of when you cast them, or is there a specific window? If you need to have Crux of Fate on turn 5 to turn the game around, you need to be sure you hit your lands on the way to it, but if you can afford to take another turn or two, it’s a different story.

Four- and five-cost planeswalkers are especially prone to this kind of issue. A planeswalker a turn behind means a turn more of threats it has to be stable against. This is part of why we see G/W Tokens play so land-heavy. It needs to cast Gideon, Ally of Zendikar on turn 4, not after playing another turn on three mana.

Spells that scale up with additional mana have a weird push-pull that depends largely on how big the upside is for spending more. If it’s just something incidental to do, like a Lightning Berserker, then you stay low. If it’s a larger upside, like awaken, then you want to bias towards more lands.

Takeaway: The better your low drops, the fewer lands you can play.

Takeaway 2: The less your high drops decrease in quality over time, the fewer lands you can play.

Takeaway 3: This is where the baseline counts for a lot of the archetypes come from. Aggro playing twenty to 21 lands is it saying it can play fine off two mana and doesn’t really want six ever. Midrange playing 24 or 25 means it wants the first few and can wait for the later ones. Control pushing higher implies it has things to do with five, six, or seven mana, like casting counter-protected threats or deploying multiple answers. These are baselines that shift due to the other modifiers, but they exist for this reason.

One last note: this isn’t just a one way street. When you start adding and cutting lands from a deck, it has a cascading effect. Adding lands pushes you to add more high drops, which pushes towards more lands, and the reverse is true.

It’s a trap to think you have to push all towards one end to find a balancing point. If you find yourself stuck with a new archetype, consider how you could shift it along the land count axis and see what new possibilities open up.