Years of building horrible decks have helped me developed a list of things to evaluate while I’m building a new deck to try to avoid falling into any obvious traps that might invalidate my deck, helping me save valuable testing time by knowing when to scrap an idea before playing any games or to simply make better first drafts, so I’d like to share some of the basic principles of solid deckbuilding I try to follow in all of my first drafts of decks now.

Yes, And…?

This one is probably a bigger concern for me than for most people. I love a good value engine. Cards that generate value are awesome. I’m reasonably likely to make a Pioneer decklist that starts with something like:

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, and I’m sure I could round that out into a solid deck. Though admittedly, a lot of that is because I’m bailed out by Uro being an absurd card that generates value, which is what I’m after here, but that also accidentally wins the game, which maybe makes it not the best way to drive this point home…

What I’m trying to get at is that I’m the sort of person who can get excited about the part of the game where I start targeting Cloudblazer with Thassa, Deep-Dwelling and lose sight of the fact that I’m supposed to be trying to actually kill my opponent. Drawing cards is great, but you need to make sure those cards are actually doing something at the end of the day.

I don’t know how many of you are Euro-style board game players, but it’s very common for the basic mechanic to be that you can create an infrastructure that generates resources and you can create an infrastructure that generates victory points, and most of the game is about balancing when you shift from focusing on generating resources in the early-game to converting those resources to points in the mid- to late-game (as well as maximizing the efficiency of both of those steps – strategic focus versus tactical focus).

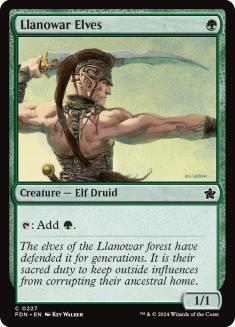

Damage is like the victory points of Magic and it’s easy to get lost scaling up your resource production forever with decks that just generate cards. You need to start getting points somewhere along the line, and Magic often offers a pretty short timeline to do that. Llanowar Elves into Gruul Spellbreaker is exactly one turn of building up an infrastructure to get resources before we start converting to a victory point building system.

Sometimes in Magic we can afford more setup, but not very much. Take ramp decks, for example. In Modern, we’re looking at spending between one and three turns ramping for a payoff that happens on Turn 3 or 4. In Standard, you can maybe wait until Turn 5 for your big payoff if it’s big enough and your ramping has created some speed bumps for your opponent, but games of Magic are short, and whenever your deck involves putting a lot of stock into establishing an engine, the payoff needs to be game ending. If Panharmonicon is involved, you might need a reality check about how much set up you’re looking at.

As a side note, I think the reason people like Commander is that the higher life total leads to an expectation that the games last a few more turns, which changes the time that you need to start converting your resource engine into a victory engine. That means there’s more time to build a good resource engine and take advantage of it, which means cards like Panharmonicon actually have a chance and building engines is actually really fun. It’s just also not what competitive Constructed Magic really rewards.

The iconic Commander setup card that competitive Constructed doesn’t give time for.

So your deck does something and it’s not just a pile of increasing quantities of air. That’s a great start. Up next:

Speed Test

Realistically, when is your deck going to kill your opponent? Full disclosure – I’m not really into killing my opponent. I rarely design decks for speed. I’m more likely to assume I’ll figure it out after the fifth Cryptic Command these days, but if you’re building an aggro/combo deck in particular, you really need to think about when you’ll win the game and re-evaluate for when you win through various common forms of interaction.

This speed test informs how much interaction you need. If you win more quickly than everyone else, you might not need any maindeck interaction (Neobrand), but if you haven’t built a Turn 1-2 combo deck, you probably need to think about when you’re winning a race, when you’re losing it, and how you can best trip your opponent up.

There isn’t a target for the speed test; it just informs other questions about your deck.

Interaction

One trap I’ve fallen into a lot when building synergy-heavy decks, like tribal decks or decks built around some particular mechanic or common theme, is that another card that works with all my other cards always seems so much better than an off-plan card that just answers one of my opponent’s cards. Why would I want that?

Well, if your speed test isn’t leaving you in first, you need to slow your opponent down somehow and blocking isn’t always going to do that. Also, if your speed test is easily disrupted, maybe by something like removal or blocking, you’re going to need some way to keep the pressure on.

A good rule of thumb is that even the most dedicated creature decks that are fast and aggressive still need removal. It’s basically impossible to kill an opponent by attacking before they can resolve a creature that’s a huge problem for you, but for a true aggro deck, answering just the first creature that matters is exactly what you need.

For some very focused aggro decks, you’re trying to draw exactly one removal spell per game, because the second can come at the expense of too much of your clock. In these spots, I’ve found six to eight removal spells to be a good place to be. With six, you’re over 70% to find one in your first eleven cards and just over 30% to find two. If you go up to nine removal spells, you’ll draw two in the first four turns in over half your games, and that’s often too many.

The more your threats stand on their own and can win games by themselves, the more interaction you want to play. You’re happy to draw one Tarmogoyf and three removal spells, but if you draw one Thalia’s Lieutenant and three removal spells, you’re not beating anyone.

Infect in Modern sets the lower bound for the playable number of removal spells in an “aggro” deck. It gets away with that because it has a great speed test and it’s resilient to opposing creatures because most of its threats have evasion, and worst case, pump spells double as removal spells when blocking is involved. Even Infect usually plays a few copies of Dismember.

Curve

We all know it’s important to have spells at a variety of costs, but just to review, the purpose of this is to maximize your chances of using all your mana in a game of Magic. In general, the player who spends the most mana in a game will win that game. This isn’t a hard rule, of course, since the text of your cards actually matters, but everyone’s choosing cards that do relatively good things for the amount of mana they put into them, and if you can use more of your mana, that probably means you’re doing better things.

It’s also worth noting that cards on the battlefield longer have more chances to do things, so a mana spent on the first turn is more impactful than a single mana spent on the fourth turn. This means it’s really important to make sure that you can use your mana for something in each of the first few turns, but you’re also going to lose if you’ve run out of gas and the game is still going on and your opponent’s engine is still running. If you have a low curve, you need to either be confident you’re going to end most games before it matters or have some kind of mana sink or way to keep drawing more things to spend your mana on.

So what does this mean your curve should look like? Well, there aren’t exactly hard rules, but in general, I think of eight as a pretty hard cap on the number of four-mana spells I can get away with playing in a deck, and even that’s pushing it. If I want a ninth for some reason, I’m probably better-served with a five-mana spell unless the ninth four-mana spell is actually stronger than any five-mana spell I could play (which is unlikely). This is because If I have eight, I’m going to have one to cast on Turn 4 around 80% of the time before even factoring any additional card drawing or selection I might do on the first three turns (and there’s a good chance I’m doing some of that in a deck that’s planning to cast a lot of spells that cost four or more mana), so I’ll be better off with more expensive cards to follow my four-mana spells.

Three mana is a lot more forgiving. You’ll miss your fourth land drop a lot more often than you’ll miss your third, and it’s really hard to win a game where you don’t do anything on Turn 3. I think you typically want at most twelve cards that cost three, with a range between eight and twelve for decks in the 23-26 land range.

One- and two-mana spells are harder to quantify. With spells that cost three or more, your deck will get way too clunky if you have too many of them in general or too many at the same point in the curve and it’ll be really obviously problematic, but for one- and two-mana spells, it’s a lot more flexible. How many one-mana spells is really a function of what kinds of effects are available at one mana in the format you’re playing and how often your first land is going to enter the battlefield tapped. In some decks, all your spells will cost one or two mana, and some decks play no one-mana spells. In general, I’d like to have at least twelve cards that mean that my first turn won’t involve playing an untapped land and not tapping it for mana. Tapped lands can count as one-drops, but if your lands are going to be untapped, you should be able to take advantage of that.

With two-drops, I think twelve is another solid cap. Being an even number is tricky because it means you’re wasting your odd amounts of mana; if your hand is just lands and two-drops, you’re wasting a mana on your first and third turns, and that’s unacceptable. Beyond twelve two-drops, you’d be better served making some of them one- or three-mana cards. As with three-drops, I’m very comfortable only playing eight two-drops, but with fewer than that I start getting worried about wasting my second turn.

Note that when I build a deck, I literally go through this process. I list the spells I want in casting cost order, starting with the most important cards at each cost. Once I’ve listed twelve spells at any given cost, I move up to the next cost and I don’t move up to the next cost until I’ve listed at least eight at the current cost. Once I have that initial list I go back and tweak the numbers some, but that gets me in the right range.

Mana

Are you playing the right number of lands? Do you have enough access to each of your colors to cast your spells?

Frank Karsten wrote an article a while back that I know a lot of people follow religiously, but it doesn’t cover everything. For example, there’s a substantial difference in how many red sources you need to support Goblin Guide, which you really want to cast on the first turn, compared to Lightning Bolt, and it doesn’t address the issue of how much of your deck relies on hitting a certain cost, so take it with a grain of salt, but it’s an excellent starting point.

Making a List

I’d summarize these steps as follows:

- Make sure your deck does something. Does this actually offer an output that leads to victory?

- Make sure your deck will do that in a realistic time frame. Do I have the tools to make sure I can get to the point where I’ll realize that output?

- Make sure your deck’s basic functionality is covered. Can I use all of my mana?

- Do my spells fill out a curve that will mean that I have the right cards to spend all of my mana on to cast all of my spells?

- Will the lands in my deck consistently allow me to cast those spells?

There are a lot of different macro-level approaches to building decks. Sometimes we modify an existing deck, which is essentially building from a template. Sometimes we build a deck specifically to attack an existing strategy or set of strategies. Sometimes we build to maximize a particular interaction, card, or set of cards. Regardless of your approach, any deck should have all of these bases covered.

Bonus: If you’re hung up on the sketch of that Uro deck from earlier, I might round it out to something like this:

Creatures (21)

- 4 Satyr Wayfinder

- 4 Glint-Sleeve Siphoner

- 4 Rogue Refiner

- 2 The Scarab God

- 1 Hostage Taker

- 3 Atris, Oracle of Half-Truths

- 3 Uro, Titan of Nature's Wrath

Lands (23)

Spells (16)