I have never thrown a small man at a large dartboard. I don’t have a mansion, I’ve never done Quaaludes, and I’ve never even stepped foot on a yacht.

It’s possible that some people in Magic finance are living the high life, but most speculators I know aren’t even making enough money to consider making Magic their full-time job. You may think the community is a bunch of Jordan Belforts, but it’s mostly just hungry grinders with a couple of extra cards tucked away in their closet.

No matter—speculators are Public Enemy No. 1 in Magic right now, and everyone wants our heads. With furious spikes on fringe cards like Fist of the Suns, Norin the Wary, and Summoner’s Egg, someone out there must be getting rich, right? Just like in The Wolf of Wall Street, it appears as though a group of speculators is working behind the scenes to raise the price of terrible rares, dump them on the public at inflated prices, and walk off with everyone’s money.

Is this actually happening? Can we beat them, or is it better to join them? Is Magic doomed to a permanent boom-and-bust cycle? Let’s find out.

The Problem With Speculation

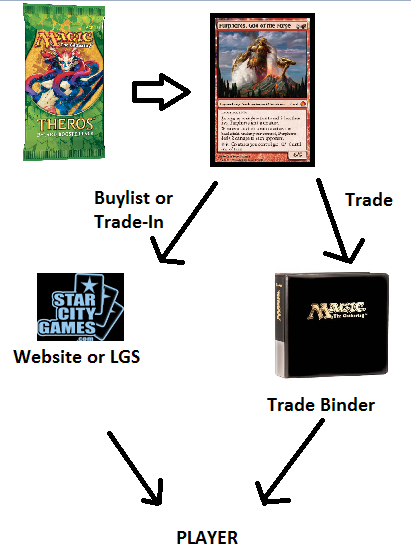

In an ideal world, the Magic economy should look something like this:

Stores and websites are necessary middlemen because they provide an important service. If you open a card that you don’t need, you can trade it in to the store or sell it to them for cash, which you can then use on cards that are more useful to you. Most sites will buy any Magic card as long as the price is right, saving you from having to find a buyer by yourself. Other sites will act as a broker, allowing direct sales between seller and buyer in exchange for a commission.

Webites and stores also make it easier for you to buy the cards you want without having to wait for someone at your local store to open them and trade them to you. In the days before large Internet stores, local card availability was a much bigger barrier to formats like Cube and Legacy. If you didn’t have a well-stocked LGS, finding a specific card you needed was a huge pain in the neck. I remember offering two or three times what a foil Avatar of Woe was worth to the one kid in my store who had one and still getting turned down. Today I can click three buttons on a website and have it delivered to my house tomorrow afternoon.

Doing business with stores also helps keep the infrastructure of Magic humming along. Your LGS uses some of the money they make off selling singles to keep the lights on and justify keeping table space around. Some websites use their revenue to pay for columnists and video producers as well as tournament series.

Trading—my personal favorite way to exchange cards—provides players with an alternative to dealing with a store or site. Because the transaction doesn’t have a middle man, you can get a much better deal. In exchange for this, though, you’re limited in selection to what your trading partner has available and what he or she is interested in getting from you in return.

This is why suitcase-level value traders often demand a premium when making a deal. If they have every decent card in Magic available and are willing to accept nearly anything in return as long as the price is right, they’re operating more like a site or store than an independent trader. I like dealing with traders like this when I’m after something big or odd because they offer the selection of a store but often without demanding quite as big a cut in return, but I’d rather deal with a normal trader or a store when trading for casual cards or Standard staples.

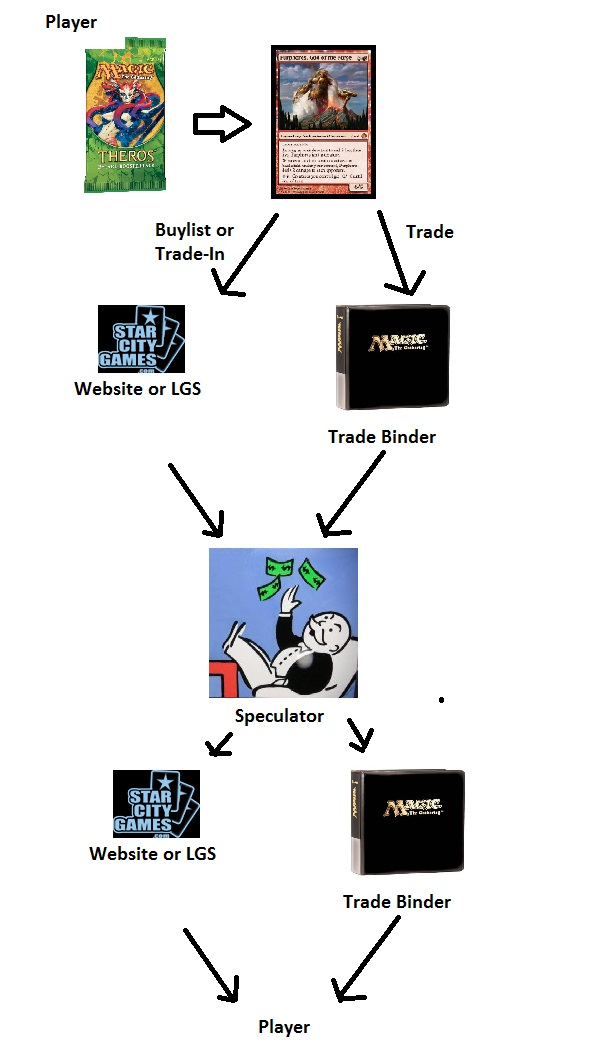

Now let’s see what happens to the market when we add speculators into the economy:

Wonder why people hate speculators so much? This is why. Instead of adding just one more middleman to each transaction, speculation adds two. Because most speculators don’t own their own store or website, the cards they buy have to be filtered back through normal channels before they reach the players who actually want them. This makes it harder and more expensive for everyone to buy cards because three people are now demanding a piece of the pie instead of just one.

This is also something that many speculators forget when they rush out and buy three dozen copies of some spiking rare. Let’s use Genesis Wave, a card that spiked two weeks ago, as a case study:

Three months ago you could pick up Genesis Waves for about a dollar. They retailed between $1.50 and $2, but if you were persistent, you could find them for less than that. Right now Genesis Wave retails for $5.99, and there are quite a few copies available at that price point. That’s a guaranteed profit of $20 per playset, right?

If you’re a regular reader of this column, you know that isn’t close to true.

Let’s start by unpacking the true sale price of Genesis Wave right now. Unless your name is Pete Hoefling or Ben Bleiweiss, you don’t have the infrastructure in place to get $5.99 per card. Based on the most recent eBay completed listings, the true price anyone can sell Genesis Wave at right now is closer to $16/playset shipped. That’s $4 per card.

Now let’s deduct the 13% that eBay and PayPal will take as well as the roughly $0.20/card it will take to ship playsets in envelopes with top loaders. That brings us down to $3.28 per card.

So you’re still pretty happy if you bought Genesis Waves for a dollar a card because you’ve made about nine dollars per playset. You’re a spec champion!

The problem is that almost no one actually bought these cards at $1 each. The card had already started trending upward by early December, well before the spike, which means most people who bought in when the “buy Genesis Wave!” train started leaving the station ended up paying about $2/card. If you did that, you only made about $5/playset in profit, which is still pretty decent but isn’t going to come close to paying the bills. Once the card actually started soaring, the price per playset rose immediately to $4/card before peaking closer to $5 or $6/card and dropping back off again. Anyone who got in a little late—like a couple hours after the story broke—ended up spending $4 each on Genesis Waves under the misguided hope that the card would hit $10. These people all lost money.

Even the people who bought in at $2/card didn’t make out very well. $5/playset profit is amazing if you’re a large retailer selling hundreds of cards a day, but if you’re just a guy or gal hoping to make an extra buck on the weekend, it probably isn’t worth your time. The card didn’t spike enough to allow you to out these cards to a buylist at a profit, which means you’re going to have to deal with eBay or an eBay alternative. That means finding pictures, looking up prices, listing cards, adjusting the price if the cards don’t sell, buying shipping supplies, packing up cards, going to the post office, and possibly dealing with irate or scumbag buyers. Unless you have an infrastructure in place already, you’re making less money per hour doing this than you would at a minimum wage job.

If speculation is secretly kind of unprofitable, though, why does it keep happening?

Death By A Thousand Cuts

How hard is it to buy out a card?

Let’s pretend for a moment that Beacon of Tomorrows has just showed up as a four-of in a deck that won a Modern Daily Event. I’m choosing this card because it’s always had a decent amount of casual demand but has never had a price spike due to competitive play. It retails for $3.99 right now, which is pretty close to the price it’s always been.

StarCityGames.com has 58 copies of the card available, including all of the NM, SP, and MP copies along with all of the foreign and foil versions. There are about 118 more listed as buy-it-now on eBay (one seller had an undisclosed number listed), though many of those are foils and some are already prohibitively expensive due to international and aspirational listings. A popular site that aggregates individual sellers lists 79 normal copies and 16 additional foils. A quick rundown of other popular Magic retailers reveals the following additional numbers of copies in stock: 32, 7, 30, 5, 12, 2, 0, and 10.

That gives us a total of 353 Beacons of Tomorrow available through the most popular channels. This isn’t the total number of copies available online right now—there might be as many as a couple hundred additional copies for sale on smaller sites that I didn’t include—but if those 353 copies disappeared this afternoon, you’d be hear about it all over Twitter and r/mtgfinance.

You wouldn’t even have to buy out all those Beacons to get things started though. At least fifty of those are foil, which means you could get movement going on the card simply by buying out the 300 normal copies. At an average price of about $4/card shipped, you’d be looking at an investment of right around $1,200 to tip the market.

This is certainly how some buyouts happen. When Hall of the Bandit Lord jumped last year, it went from being on no one’s radar to being sold out everywhere in a matter of minutes. That was clearly the work of one person or a small group of people working together. Most of the time, though, these buyouts aren’t organized at all.

Let’s go back to my hypothetical Beacon example. Once that 4-0 list goes up on the Wizards website, people would start buying playsets so that they could build the deck themselves. With only 300 easily available copies out there, all it would take would be 75 people buying one playset each for the card to sell out.

At that point, the word would start to spread. The fact that the card had become difficult to find would lead to something of a panic situation where speculators would be scrambling to get in on the ground floor and Modern players would be jumping at their last shot to get in before the price spike. The cards would disappear off the smaller sites, and then the foils would start going. By the end of a couple of hours, no copies of Beacon of Tomorrows would be available anywhere.

At this point, a few copies would start hitting the market again at significantly higher prices. This would cause people to say things like “Beacon of Tomorrows is now a $10 card” even if no copies of the card are actually selling for $10 each. One of the major sites people use to track prices uses the mean average of list prices, so if there’s only two or three copies available that are listing for $15 each that would be “the new price,” regardless of actual demand. People would bemoan the ruthless speculators, and the cycle would begin anew.

Demand & Unreal Spikes

One of the terms I’ve heard thrown around the speculation community lately is the theory of the greater fool. In Magic finance, the theory basically boils down to this–the underlying demand of the card doesn’t matter as long as you can find someone else to unload it to at a higher price. It doesn’t matter if the Beacon of Tomorrows deck is good—if you buy them at $4 each and sell them to someone for $6 each, you’ve made money. It doesn’t matter if the other guy makes money or not—as long as someone is willing to be more foolish than you, you’re golden.

This is somewhat true, but not to the degree that most people think it is. Let’s use Disrupting Shoal as an example. On December 17th, the card was featured in a Travis Woo deck that people were excited to try. Before that point, playsets were selling between $8 and $9. After that, they were up to a whopping $35.

But how many people were actually willing to pay that higher price? According to eBay completed listings, 18 playsets sold in that range over the next few weeks. Most of those playsets were sold by the same store. There are other sites where people buy cards from speculators too, of course, but even if 50 playsets were sold at $35 each, that isn’t many greater fools.

The card hasn’t dropped back down to $2 so most people who bought in before the spike are probably still happy with their purchase, but playsets of the card are now sitting unsold at $20 each. Without the “buy buy buy!” hype of a price spike behind it, the only people interested are those who actually want to play the card in a deck. All the speculators looking for greater fools are out of luck.

And what of those 50ish fools who bought in at $35/set? Most of them did so within the first day or two of the spike, which means that the people who made money off of them already had Disrupting Shoals sitting around ready to be shipped. If you bought in when you heard about the price going up, you probably didn’t get them in the mail to flip until the peak had already passed.

I also expect the number of greater fools to keep going down. Part of why speculation has gotten so out of hand lately is an increased amount of attention being paid to Magic finance. No one wants to miss out on the next big thing, so everyone tries to buy their personal sets before the price shoots up. Once people realize that cards like Genesis Wave and Fist of Suns aren’t going to be $10 forever, they’ll get more patient. The number of people buying cards like these at “greater fool” prices will shrink. This will make speculation less profitable in turn, which should lead to less of it.

Can you make money selling cards to greater fools? Sure! I’m a huge proponent of selling into hype. If you’re speculating, though, don’t forget to factor shipping time into your equation. Chances are that every other speculator is getting their playsets at the same time you are.

Don’t even think about selling cards you don’t have in your hand by the way. So many sellers today refuse to honor sales of spiking cards, including shops that used to be good about doing it. This is another pitfall of speculating—all for the cards you buy that don’t spike will ship, but only some of your good specs will actually show up.

The Dangers Of Unregulated Markets

Why aren’t eggs $20 a carton? Why do cable packages cost $80 a month? Why can’t I lie to my investors about how my company is actually doing this quarter?

Capitalism is a free market system. In theory, that means that everyone has an equal chance to compete for buyers of goods and services. In a perfect world, the best and cheapest products will always push lesser options out of the marketplace, creating a system that encourages competition and innovation.

The reality isn’t quite so neat. Without honest business reports, it’s impossible to know which companies actually are producing the best and cheapest products and which are using deception to get bogus investment capital while trying to force their competition out of the market. Some industries, like cable companies and diamond cartels, only have large companies that have bought out or shut down the competition so that they can charge whatever they feel like without having the need to innovate or compete. Other industries, like agriculture, have some restrictions placed on them by the government to discourage speculation. After all, how would you like it if food prices all over the world doubled overnight because a bunch of greedy businessmen decided that they needed to jump in the middle and make money off the fact that everyone needs to eat?

This is why most moderate capitalists believe in some government regulation. By preventing too much speculation over necessary goods, keeping everyone honest, and keeping monopolies from taking over entire industrial sectors, innovation and competition can thrive. In fact, many argue—and I agree—that the massive deregulation over the past thirty years is what led to the financial crash and the current state of the global economy.

Like it or not, the Magic economy is a fascinating glimpse into a totally unregulated market. There is no SEC. There is no oversight at all. If I have insider information—based on, say, advance knowledge of the next set, breakout tournament deck, or series of judge foils—I can use that information to make a killing buying and selling singles. No one can stop me. It probably happens all the time.

Anyone can attempt to corner the market. Anyone can charge whatever they like for any card. If I want to buy every Dark Confidant in existence and charge $10,000 each, I can. The only problem with that of course is that Wizards of the Coast could always print more whenever they felt like it. Working in Magic finance is like being in a libertarian utopia where god throws lightning bolts at the market whenever he darn well pleases. I think a lot of southern politicians would enjoy it if they gave it a shot.

Most people who don’t like rampant speculation are going about things the wrong way. By calling speculators scumbags and appealing to their sense of morality, all you’re doing is shouting at the darkness. We as a culture have made very little progress asking people to give things up by appealing to their sense of right and wrong. Want people to start recycling more or drive less? Don’t tell them it’ll help save the planet—offer them an economic incentive or a way to make things easier. People didn’t stop pirating music because of moral outrage. They did it because using Spotify was easier. Very few people give stuff up voluntarily because it’s the right thing to do–they do it because something else is easier or makes more sense.

That said, it’s worth remembering that this is a zero-sum community. Every dollar you make is an extra dollar that another player has to spend. If you want Magic to stay healthy and vibrant, try to make sure that you’re making a positive contribution to the game. I don’t write this column to help people make a living jacking up the price of cards for no reason. I do it to help players make smart decisions so that they can afford to fully participate in a very expensive hobby.

If you want rampant speculation to slow down, stop buying spiking cards at inflated prices. Are you actually building that Norin or Summoner’s Egg deck? No? Then leave those cards alone. Refuse to pay more than you have to for any card you don’t absolutely need. Magic has thousands upon thousands of cards, and at any given moment only a few of them are being bought out. Once enough of these new fly-by-night speculators lose their shirts a couple of times, they’ll give up and move on.

On the flip side, it’s important that everyone realize that a real increase in demand is going to lead to the price of a card going up. This is unavoidable. Unless systems were put into place to keep cards artificially cheap –something that would actively damage Wizards’ business model by the way—cards seeing a lot of play will rise in price. This in turn means that people will keep attempting to speculate, trying to beat the market and make a killing buying low and selling high. It is going to be a part of Magic for as long as the game continues to exist.

If you want to be a speculator, I suggest sticking to cards that have strong fundamentals, not hype. Stoneforge Mystic was a great spec in November, not because people were talking it up but because the underlying metrics showed that it was an undervalued card relative to how many exist and how much play it sees. “Zig when others zag” is a well-known investors’ koan, and it applies well here. While everyone else fawns over the current market darling, do some research and see if you can figure out what card is undervalued even though no one is talking about it. That’s where you end up finding your $1 Genesis Waves that you can then sell a few months later when they spike.

This Week’s Trends

- I was finally able to get a look at the Chinese fakes with my own eyes for the very first time. Granted, it was through a webcam, but with the help of Josh, one of my readers, I was able to see what we are up against. The truth is that while the fakes look fine in a sleeve at a glance, you can tell them apart when compared with their legitimate Magic card counterparts. The color is washed out on both the front and the back of the fakes, and I was able to spot the fake right away when confronted with both. The fakes also do not pass the bend test or UV test. Josh also assured me that outside a sleeve they do not feel right and have a much glossier finish. Unless someone produces a better caliber of counterfeit—hopefully something that will never happen—I’m not worried about these fake cards crashing the Magic market. Stay smart and vigilant and you’ll be ok.

- Watch this space next Monday for my full Born of the Gods set review. For now, I recommend staying away unless you absolutely need to have Brimaz for a deck tomorrow. He will likely remain high for a while, and I like him as the marquee card in a fairly weak set.

- Bitterblossom has skyrocketed thanks to speculation that it will be unbanned in Modern. I don’t think this will happen, but if it does, there’s very little room for further growth. It’s already sold out at $30! Stay away.

- Grove of the Burnwillows has gone up based on legitimate Legacy play, as have foil copies of Punishing Fire. These bumps should stick as long as the deck continues to do well.

- Mox Opal continues to rise based on Affinity being an otherwise affordable tier 1 Modern deck. The card will probably continue ticking up until it gets a reprint, possibly in the Modern Event Deck this spring or a second Modern Masters set. It has a very high ceiling.

- Liliana of the Veil has started to move a little too. This is another card with a legitimately high ceiling and very good underlying metrics.

- Threads of Disloyalty has started to perk up a little. It’s a good card with room to rise.

- Cavern of Souls has finally begun moving. I loved this as a spec target back in the autumn, and this is your last chance to buy in cheap.

- Xenagos has started to move a little thanks to strong R/G cards appearing in Born of the Gods. It’s possible that this card will start seeing more Standard play, which would raise the price significantly.