When did you start playing Magic? Was it during the Internet age of today, where Magic articles and websites are all around us? Maybe you learned during the day of The Dojo as the one real place to find all of your Magic info. Perhaps your Magic habit began even earlier than that. For some of us, Magic has been a lifelong habit. I started playing in late summer of 1994 when I was 17. Today I’m 35 and literally have been playing Magic for more than half of my life.

When I started playing, we had magazines as our primary source of info on Magic. In order to supplement this lack of information, companies began printing books on Magic. As someone who loved the game passionately, I purchased a few of these books here and there over the years.

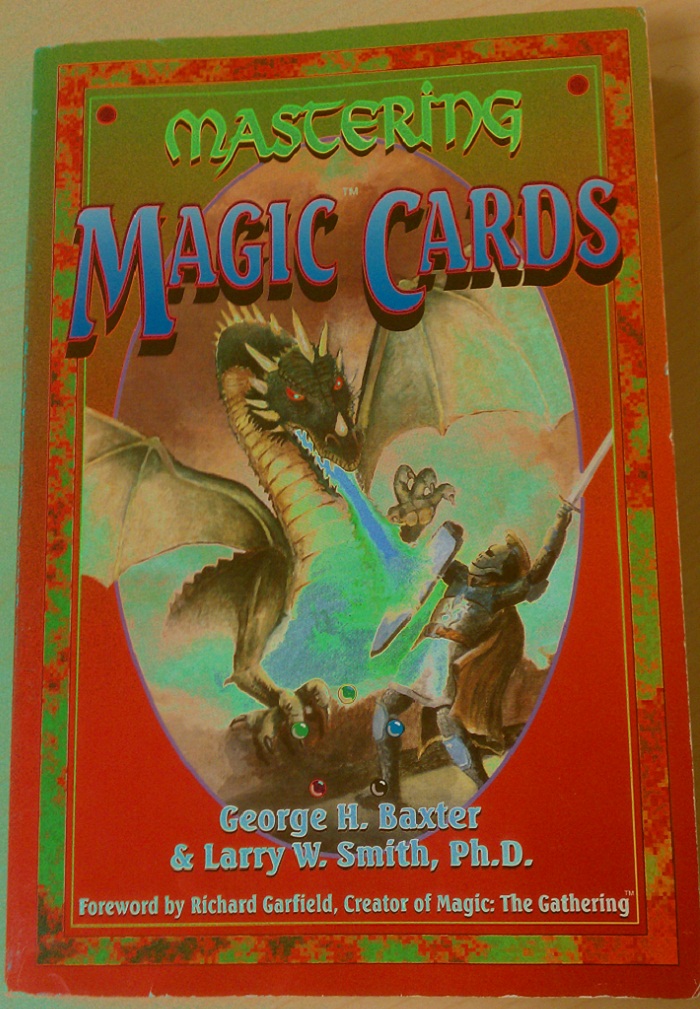

One of these books was called "Mastering Magic Cards" and was published in 1995. I recently found my copy in the back of a box of books while trying to fill some new bookshelves in my apartment. I sat down to read it again and inspiration struck. This would be a great article topic! I could read the book and then comment about how well it may or may not hold up today. In the book’s own words:

So this book wanted to be more than just a guide to what cards were available. It sought to stand the test of time. Well, it’s 17 years later, so let’s see how well it did! The book is about 250 pages long, but the last 100 or so are an encyclopedic list of every card in Magic along with ratings on their combo-potential, versatility, and ability to stand on their own. Here’s my copy of the book:

Let’s crack open this bad boy and take a look under the hood!

Section 2 – Getting Started With Magic Cards

The book is divided up into sections, so let’s look at it in order. We’ll skim over some (such as "Matt’s Thumper Deck") and stick with the strategy ones. While it opens with such charmers as a sample starter deck and where to buy things, it quickly moves into tips about how to build your first deck. Great! What advice does this book give new players?

- "You should keep your deck at 60 cards and not go higher." Good advice, check.

- "You should have 20 lands and 40 other cards." Wait, what? One of the biggest issues we’ve had is weaning people off the 20 vs. 40 rule for the past bazillion years. In fact, a note to the beginner tells them that some decks can reduce their count to 27% land and some unusual decks may require as many as 40% land. So play 20, but maybe as low as 16 or as high as 24 in rare cases. That’s really bad advice for a new person. My starting point for most decks is 24, and I often go to 26 and sometimes lower, but it’s a rare deck that needs fewer than 20 lands. This does not pass the test of time.

- The "Draw Rule" — "If you have the ability to draw more cards than your opponent, then you will be provided with more options." Card advantage is always a valuable concept to discuss, and since this section is right at the front, that’s great.

This section finishes off by taking a Starter deck and a few boosters to build a deck to show how it’s done. Basically, he was building a sealed deck of 60 cards. He then lists trades that he made to improve his deck. They include trades such as, "My Hill Giant for a Dark Ritual," and, "My Plateau for Wheel of Fortune." It’s fun to read.

Section 3 — Strengths and Weaknesses of the Five Colors

This is a fairly uninteresting ten pages on the colors and what they do. We all know this stuff by now. Here’s more on black and white and…ho hum. There’s also no major strategy discussion here.

Sections 4-5 — Proper Playing Techniques and Good Basic Deck Construction

Alright, here we go! The meat of the deck is in the next few sections. Are you ready for the proper playing techniques and deck construction, 1995-style?

- Hold your instants until they have maximum value. Don’t blow a Giant Growth just to deal three extra damage. (This is important information for newer players, true.)

- The probability of drawing cards is gone over extensively for many pages. It’s a bit much; you could just present the info and move on in a page.

- Space is spent on fifteen things that cards do, from discard to counters to fast, efficient creatures. It’s an interesting breakdown. It spends some time on building versatility into your deck so you can answer a lot of threats and gives sample decks and cards. This seems like pretty useful stuff.

- Cheap mana creatures are better than expensive ones that are bigger and stronger. Kird Ape is compared to the Elder Dragon Legends. While this was certainly true then, today’s decks have lots of very powerful creatures in the four, five, and six cost slots (or more) that are quite successful. The power of creatures has risen significantly, and this information is no longer to date. Comparing modern creatures like Goblin Guide to Primeval Titan is no longer valuable as a way to show how early creatures are so much better. (Plus, this was living in an era of Sinkhole, Strip Mine, Hypnotic Specter, Dark Ritual, Counterspell, Armageddon, and Mana Drain—I’m sure we’ll talk about this more.)

- Use and create clever decks and sideboard in things your opponent has not seen so you can have a surprise advantage. I’m surprised alright. Surprised that this book has spent so much time on sideboarding, especially in the first few sections. I would’ve moved that to a later section, but the authors are certainly correct. Surprise is a good thing, and being unable to predict what your foe’s deck can play havocs with trying to stop them.

Sections 6-10 — Decks and Stuff

A large portion of the book is spent on different sample decks and exploring them. How should you play this deck or build that deck? It’s interesting to see deck construction during the era before concepts like the mana curve were developed. For example, here’s a sample burn deck given in one chapter:

The Flame Thrower

4 Lightning Bolt

4 Chain Lightning

4 Fireball

4 Disintegrate

2 Hurricane

2 Earthquake

2 Balance

2 Disenchant

2 Howling Mine

2 Black Vise

1 Sol Ring

2 Basalt Monolith

1 Ivory Tower

2 Stream of Life

2 Fork

1 Wheel of Fortune

1 Jayemdae Tome

5 Forest

5 Plains

12 Mountain

Um, wow. Why do we have a three-color burn deck with no use of duals, Birds of Paradise, or Untamed Wilds to smooth mana? (They don’t shy away from using them in later decks. The Birds being killed by Hurricane doesn’t really apply here since Hurricane is included solely to slip past Circle of Protection: Red at the end when you’re ready to kill someone.) You have fourteen X spells but no acceleration beyond two Monoliths and a Sol Ring?

Also note the 22 lands. Why are cards like Ivory Tower and Stream of Life even here? This seems very susceptible to the common Land Destruction decks of the day , which he mentions earlier as a strategy versus burn decks and yet isn’t prepared against it here. While some of the basic principles are still true, it’s obvious that this deck really doesn’t stand the test of time.

Anyway, he continues principles when discussing these decks, so let’s look at them:

- Hold your creature removal until its absolutely necessary, especially Lightning Bolts. Advice which could stand to be repeated to many of today’s players.

- Land Destruction is defeated by speed. With cheap cards in your deck you can manage to play a few creatures or have Counterspell online before cards like Ice Storm and Stone Rain are played against you. (In what context the above deck is "fast" I have no idea). At least the LD example they give is one of the nasty ones running around tournaments at the time with Moxen, Lotus, Duals, and other fully powered cards.

- Speed also beats Counter decks, and it is vital to have it. This is classic advice most everyone would agree with. When you don’t have Scragnoth, force your spells out quickly so you don’t run into a counter-shield.

- There is another section on how speed defeats hand destruction as well. If you drop those fast creatures, then your plan will be in place prior to your foes disrupting your hand. (This is also true, but one of the most devastating plays in Magic during this era is the dreaded Dark Ritual into Hypnotic Specter, and speed does little against it. Lightning Bolt, Swords to Plowshares or even Unsummon are your allies here.)

Here’s the sample aggro deck they use to demonstrate how a fast deck can dance around some of these other things. I think it’s messy.

Charles’ Kird Ape Deck

4 Kird Ape

4 Scavenger Folk

4 Llanowar Elves

4 Giant Spider

4 Grizzly Bears

4 Lightning Bolt

4 Disintegrate

4 Fireball

2 Hurricane

2 Tranquility

4 Giant Growth

1 Regrowth

1 Wheel of Fortune

9 Mountain

9 Forest

This was released after Fallen Empires, so I consider this a big swing and a miss. After all of the emphasis the authors have placed on decks needing to be fast to beat Land Destruction, Discard, and Counter decks, this is what he comes up with. First of all, as a sample deck it looks too similar to the Burn deck.

Secondly, a deck with 18 land and a ten-set of X spells is hardly consistent. This whole deck discusses building decks in a tournament context, although it never specifically says it’s just for tournaments. Giant Spider doesn’t make the cut in anything.

Here’s the deck they should’ve used because it was the "Great White Hope" against all of these over strategies running around, and you saw it a lot.

Great White Hope

4 Savannah Lions

4 White Knight

4 Icatian Javelineers

4 Tundra Wolves

4 Order of Leitbur

4 Thunder Spirit

2 Serra Angel

4 Crusade

2 Jihad

4 Swords to Plowshares

2 Disenchant

2 Armageddon

20 Plains

This is what good aggro decks looked like. It may have needed some extra mana and/or more Armageddons and the sideboard was chock full of Circles of Protection, Karma, Conversion, and Cleanse. This was pretty standard. Imagine going against an LD deck and dropping Savannah Lions followed by White Knight. As they destroy your lands, you can still drop Javelineers or Tundra Wolves or maybe even slip down a Crusade. The LD person takes too long taking out your lands ,and they lose.

You have defense against a quick Hypnotic Specter (Swords), and it works just as well against another aggro strategy of the era: using your powerful artifact mana to fuel a quick Juzam Djinn or Erhnam Djinn. This is more consistent, smooth, and certainly qualifies as faster. Even with the harder to find and expensive Thunder Spirit and Jihad, it’s still a lot cheaper than all of the power running around in decks.

Section 11 — Advanced Deck Construction

Now that the book has spent several chapters on sample decks and strategies, it’s time for advanced construction. I can’t wait!

Now that’s an interesting claim! We’ll see if the authors can back it up, but I’m sure we’ll talk about Prison decks (decks that use Winter Orb and Armageddon to lock down a foe’s mana) and The Deck (a Blue/White deck that was built around card advantage inherent in the colors and the powerful cards therein, although it may not have been introduced when this was written.) Let’s see!

- Advanced decks are built around concepts, not powerful cards. Powerful cards that don’t fit in are chucked aside because the core idea is the concept. I agree in one context but not another. Caw-Blade dominated so much because it included the best cards. I think advanced decks are those that have a concept that includes the best cards. Arcbound Ravager is silly powerful, so you play an Affinity deck. Sensei’s Divining Top has a lot of power, so let’s find a combo that works with it (Counterbalance). Did Faeries dominate during Lorwyn because they had a cute theme or powerful cards? You understand the idea. Still, I think this is a good starting point.

- The most powerful effects are game changing ones like sorceries, artifacts, and enchantments. Examples given include Howling Mine, Wrath of God, Tranquility, Nether Void, and Ankh of Mishra. Considering that this is the era of weak creatures, I would agree. Today I’d say the most powerful effects are creatures with a high p/t to casting cost. Is there any game changing sorcery that was as ubiquitous as Tarmogoyf has been? Easily playing a 3/3 for one mana was banned. Decks are rife with 2/2s on the first turn, 3/3s on the second, and then they spike from there. While I agree with their thought then, I think things have morphed to the dominant rise of creatures (and rightfully so btw).

- The last part is on the metagame. Make sure you know what decks are running around and prepare for them. This is timeless advice and still works today.

Sections 12 -14 — Advanced Decks

Now we’re going to see some advanced decks. Are you ready?

Okay, I have to admit that the first deck is downright lethal in this era.

The Abyss

4 The Abyss

4 Mana Drain

4 Juggernaut

4 Clay Statue

4 Disenchant

2 Amnesia

1 Mind Twist

3 Lightning Bolt

2 Power Sink

1 Disintegrate

1 Ancestral Recall

1 Time Walk

1 Braingeyser

1 Demonic Tutor

1 Sol Ring

1 Basalt Monolith

5 Moxen

1 Library of Alexandria

1 Mishra’s Workshop

4 Mishra’s Factory

4 Underground Sea

4 Volcanic Island

4 Tundra

2 Island

That is a truly devastating deck built at the frontline technology of the day. Perhaps you or I could build a better deck from those cards today, but this would still be powerful. You can’t deny this deck!

- The next example deck is not as powerful. It’s a deck built around Millstone, Field of Dreams, and Balance. Sure, it packs Moxes, dual lands, and other power. But at the end of the day, it’s supposed to be a Millstone deck. How does it keep itself from being attacked by creatures? Four Icy Manipulator and four Balance. It’s actually not a Millstone deck, despite what the authors tell you. It’s a deck designed to drop its hand very early, and with few lands, no hand, and no creature power a Balance can devastate a foe, and then the deck has a non-creature means of winning. (It won’t be long before Balance is restricted.) That non-creature winning condition could be an artifact damage source or Mishra’s Factory, but it’s a Millstone. The fact it’s a Millstone is sort of superfluous. It appears very weak to aggro decks barring a quick Balance, but in an environment against all of these slower decks it seems like it might have some juice.

- The third section is dedicated to a deck built around artifact damage and prevention. It was decently played during the era, and it involves cards like Armageddon Clock, Martyrs of Korlis, Copper Table, Reverse Polarity, and more. It uses Ashnod’s Transmogrants to turn an opponent creature into an artifact so it can prevent the damage. It even has a full set of Artifact Wards. It’s not a bad deck because it’s fun! I’ve built a version before. But it’s a bit unwieldy as a good example of an "advanced deck."

Section 15 — Constructing Cheap, Effective Decks

We’re almost done with the book. The remaining sections are on cheap decks, trading, and a conclusion. This is the last section on strategy, and we’ll skip the rest.

There are two quick examples of cheap and effective decks. The strategy here is thin. Between the decklists and comments on the decks themselves, this chapter is just five pages long. It recommends that if money is an issue to steer clear of decks that really need an out-of-print card to make it work.

The first sample deck is built around Power Surge and Circle of Protection: Red. It has Tundra Wolves, Dwarven Warriors, White Knight, Orcish Artillery, Sunglasses of Urza maindeck, Firebreathing, Pikemen, Fireball, Disintegrate, Alabaster Potion, and Disenchant. It’s not a bad deck at all, but some of those cards are not good (like Firebreathing and its easily two-for-oned nature). Where’s Dragon Whelp, Granite Gargoyle or Dragon Engine?

The other sample deck is built around a different red rare enchantment: Manabarbs. With Kird Ape, Bolts, Wheel, Regrowth, Howling Mine, Vises, Llanowar Elves, Disenchants, Scryb Sprites, Birds, Giant Growths, and Swords, it’s an odd deck. It also only has twelve lands. You could free mulligan a hand with no land but couldn’t Paris mulligan (the modern mulligan Paris rules wouldn’t come into play for a while). So it’s not as bad of a strategy as you might think. As long as you have a land and Birds/Elves or two and a Mine, you’ll be fine.

Then the section on trading includes points such as, "Don’t let them know you want the card," and, "Don’t let them think you can be taken advantage of." Timeless stuff for all barters and negotiations.

Anyway, I hope that you enjoyed a slightly different sort of article today. Sometimes I just want to write something unusual. Considering the age of the book, it has held up well. However, it came at a time before a lot of modern inventions to building decks had arrived. Remembering that, it’s remarkably consistent from then to now, and I enjoyed reading it again.

Until later,

Abe Sargent